Prostate

| Prostate | |

|---|---|

Male Anatomy | |

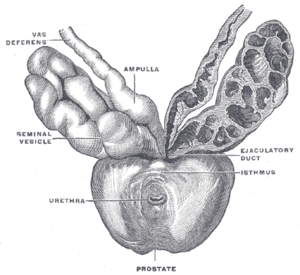

Prostate with seminal vesicles and seminal ducts, viewed from in front and above. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Endodermic evaginations of the urethra |

| Artery | Internal pudendal artery, inferior vesical artery, and middle rectal artery |

| Vein | Prostatic venous plexus, pudendal plexus, vesical plexus, internal iliac vein |

| Nerve | Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Prostata |

| MeSH | D011467 |

| TA98 | A09.3.08.001 |

| TA2 | 3637 |

| FMA | 9600 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The prostate (from Ancient Greek προστάτης, prostates, literally "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian"[1]) is a compound tubuloalveolar exocrine gland of the male reproductive system in most mammals.[2][3] It differs considerably among species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically.

The function of the prostate is to secrete a slightly alkaline fluid, milky or white in appearance, that in humans usually constitutes roughly 30% of the volume of semen along with spermatozoa and seminal vesicle fluid.[4] Semen is made alkaline overall with the secretions from other contributing glands, including, at least, seminal vesicle fluid.[5] The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival, and better protection of genetic material.

The prostate also contains some smooth muscles that help expel semen during ejaculation.

Structure

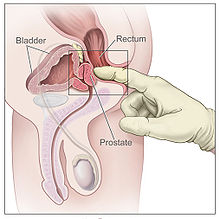

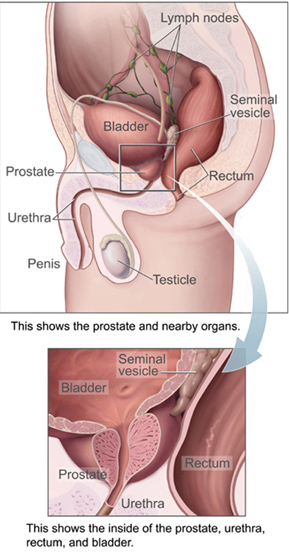

The classical description of a healthy human male prostate portrays it as slightly larger than a walnut. The mean weight of the normal prostate in adult males is about 11 grams, usually ranging between 7 and 16 grams.[6] A study stated that prostate volume among patients with negative biopsy is related significantly with weight and height (body mass index), so it is necessary to control for weight.[7] The prostate surrounds the urethra just below the urinary bladder and can be felt during a rectal exam.

The secretory epithelium is mainly pseudostratified, comprising tall columnar cells and basal cells which are supported by a fibroelastic stroma — containing randomly oriented smooth-muscle bundles — that's continuous with the bladder. The epithelium is highly variable and areas of low cuboidal or squamous epithelium are also present, with transitional epithelium in the distal regions of the longer ducts.[8] Within the prostate, the urethra coming from the bladder is called the prostatic urethra and merges with the two ejaculatory ducts.[9]

One can sub-divide the prostate in two ways: by zone or by lobe.[10] It does not have a capsule; rather an integral fibromuscular band surrounds it.[11] It is sheathed in the muscles of the pelvic floor, which contract during the ejaculatory process.

Zones

The "zone" classification is more often used in pathology. John E. McNeal first proposed the idea of "zones" in 1968. McNeal found that the relatively homogeneous cut surface of an adult prostate in no way resembled "lobes" and thus led to the description of "zones".[12]

The prostate gland has four distinct glandular regions, two of which arise from different segments of the prostatic urethra:

| Name | Fraction of gland | Description |

| Peripheral zone (PZ) | Up to 70% in young men | The sub-capsular portion of the posterior aspect of the prostate gland that surrounds the distal urethra. From this portion of the gland ~70–80% of prostatic cancers originate.[13][14] |

| Central zone (CZ) | Approximately 25% normally | This zone surrounds the ejaculatory ducts. The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers; these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles.[15] |

| Transition zone (TZ) | 5% at puberty | ~10–20% of prostate cancers originate in this zone. The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra and is the region of the prostate gland that grows throughout life and causes the disease of benign prostatic enlargement. (2)[13][14] |

| Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or stroma) | Approximately 5% | This zone is usually devoid of glandular components, and composed only, as its name suggests, of muscle and fibrous tissue. |

Lobes

The "lobe" classification is more often used in anatomy. The prostate is incompletely divided into five lobes:

| Anterior lobe (or isthmus) | roughly corresponds to part of transitional zone |

| Posterior lobe | roughly corresponds to peripheral zone |

| Right & left Lateral lobes | span all zones |

| Median lobe (or middle lobe) | roughly corresponds to part of central zone |

Development

The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the pelvic (middle) part of the urogenital sinus (endodermal origin). Endodermal outgrowths arise from the prostatic part of the urethra and grow into the surrounding mesenchyme. The glandular epithelium of the prostate differentiates from these endodermal cells, and the associated mesenchyme differentiates into the dense stroma and the smooth muscle of the prostate.[16] The prostate glands represent the modified wall of the proximal portion of the male urethra and arise by the 9th week of embryonic life in the development of the reproductive system. Condensation of mesenchyme, urethra and Wolffian ducts gives rise to the adult prostate gland, a composite organ made up of several glandular and non-glandular components tightly fused.

Histology

- Glandular cells

- Myoepithelial cells

- Subepithelial interstitial cells[17]

Function

Male sexual response

During male seminal emission, sperm is transmitted from the vas deferens into the male urethra via the ejaculatory ducts, which lie within the prostate gland. Ejaculation is the expulsion of semen from the urethra. It is possible for some men to achieve orgasm solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as prostate massage or anal intercourse.[18][19][20]

Secretions

Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars and are often slightly alkaline.[21] In human prostatic secretions, the protein content is less than 1% and includes proteolytic enzymes, prostatic acid phosphatase, beta-microseminoprotein, and prostate-specific antigen. The secretions also contain zinc with a concentration 500–1,000 times the concentration in blood.

Regulation

To function properly, the prostate needs male hormones (androgens), which are responsible for male sex characteristics. The main male hormone is testosterone, which is produced mainly by the testicles. It is dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a metabolite of testosterone, that predominantly regulates the prostate.

Gene and protein expression

About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and almost 75% of these genes are expressed in the normal prostate.[22][23] About 150 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the prostate with about 20 genes being highly prostate specific.[24] The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the glandular and secretory cells of the prostatic gland and have functions that are important for the characteristics of semen. Examples of some of the most prostate specific proteins are enzymes, such as the prostate specific antigen (PSA), and the ACPP protein.

Clinical significance

The volume of the prostate can be estimated by the formula 0.52 × length × width × height. A volume of over 30 cm3 is regarded as prostatomegaly (enlarged prostate). Prostatomegaly can be due to any of the following conditions.

Inflammation

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland. There are primarily four different forms of prostatitis, each with different causes and outcomes. Two relatively uncommon forms, acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis, are treated with antibiotics (category I and II, respectively). Chronic non-bacterial prostatitis or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome (category III), which comprises about 95% of prostatitis diagnoses, is treated by a large variety of modalities including alpha blockers, physical therapy,[25] psychotherapy, antihistamines, anxiolytics, nerve modulators, phytotherapy,[26] [unreliable medical source?], surgery, and more. More recently, a combination of trigger point and psychological therapy has proved effective for category III prostatitis as well.[27] Category IV prostatitis, relatively uncommon in the general population, is a type of leukocytosis.

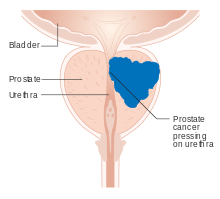

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) occurs in older men;[28] the prostate often enlarges to the point where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to urinate often (frequency) or taking a while to get started (hesitancy). If the prostate grows too large, it may constrict the urethra and impede the flow of urine, making urination difficult and painful and, in extreme cases, completely impossible.

BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. Minimally invasive procedures include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate (TUNA) and transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT).[29] These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary prostatic stent, to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms.[30] In some cases, "obesity management may be an effective method to reduce prostate volume."[7]

The surgery most often used in such cases is called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP or TUR). In TURP, an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of urine. TURP results in the removal of mostly transitional zone tissue in a patient with BPH. Older men often have corpora amylacea[31] (amyloid), dense accumulations of calcified proteinaceous material, in the ducts of their prostates. The corpora amylacea may obstruct the lumens of the prostatic ducts, and may underlie some cases of BPH.

Urinary frequency due to bladder spasm, common in older men, may be confused with prostatic hyperplasia. Statistical observations suggest that a diet low in fat and red meat and high in protein and vegetables, as well as regular alcohol consumption, could protect against BPH.[32]

Life-style changes to improve the quality of urination include urinating in the sitting position.[33] This reduces the amount of residual volume in the bladder, increases the urinary flow rate and decreases the voiding time.

Cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting older men in developed countries and a significant cause of death for elderly men[34] (estimated by some specialists at 3%[citation needed]). Despite this, the American Cancer Society's position regarding early detection is "Research has not yet proven that the potential benefits of testing outweigh the harms of testing and treatment". They believe "that men should not be tested without learning about... the risks and possible benefits of testing and treatment" which should be discussed with a doctor at age 50 or at age 45 if the patient is black or has a father or brother who acquired prostate cancer before age 65.[35] If checks are performed, they can be in the form of a physical rectal exam, measurement of prostate specific antigen (PSA) level in the blood, or checking for the presence of the protein Engrailed-2 (EN2) in the urine.

Co-researchers Hardev Pandha and Richard Morgan published their findings regarding checking for EN2 in urine in the 1 March 2011 issue of the journal Clinical Cancer Research.[36] A laboratory test currently identifies EN2 in urine, and a home test kit is envisioned similar to a home pregnancy test strip. According to Morgan, "We are preparing several large studies in the UK and in the US and although the EN2 test is not yet available, several companies have expressed interest in taking it forward."[37]

Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer

In 1983, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported a connection between vasectomy and an increased risk of prostate cancer. Reported studies of 48,000 and 29,000 men who had vasectomies showed 66 percent and 56 percent higher rates of prostate cancer, respectively. The risk increased with age and the number of years since the vasectomy was performed.

However, in March of the same year, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development held a conference cosponsored by the National Cancer Institute and others to review the available data and information on the link between prostate cancer and vasectomies. It was determined that an association between the two was very weak at best, and even if having a vasectomy increased one's risk, the risk was relatively small.

In 1997, the NCI held a conference with the prostate cancer Progressive Review Group (a committee of scientists, medical personnel, and others). Their final report, published in 1998 stated that evidence that vasectomies help to develop prostate cancer was weak at best.[38]

In other mammals

The prostate is found as a male accessory gland in all placental mammals excepting edentates, martens, badgers and otters.[39] The prostate glands of male marsupials are disseminate[40] and proportionally larger than those of placental mammals.[41] In some marsupial species, the size of the prostate gland changes seasonally.[42] The structure of the prostate varies, ranging from tubuloalveolar (as in humans) to branched tubular. The gland is particularly well developed in dogs, foxes and boars, though in other mammals, such as bulls, it can be small and inconspicuous.[43][44] Dogs can produce in one hour as much prostatic fluid as a human can in a day. They excrete this fluid along with their urine to mark their territory.[45] In many rodents and bats, the prostatic fluid contains a coagulant. This mixes with and coagulates semen during copulation to form a mating plug that temporarily prevents further copulation.[46][47] In cetaceans the prostate is composed of diffuse urethral glands[48] and is surrounded by a very powerful compressor muscle.[49]

The prostate gland originates with tissues in the urethral wall. This means the urethra, a compressible tube used for urination, runs through the middle of the prostate. This leads to an evolutionary design fault for some mammals, including human males. The prostate is prone to infection and enlargement later in life, constricting the urethra so urinating becomes slow and painful.[50]

Skene's gland is found in both female humans and rodents. Historically it was thought to be a vestigial organ, but recently it has been discovered that it produces the same protein markers, PSA and PAB, as the male prostate.[51] This means Skene's gland functions as a female prostate, a histologic homolog to the male prostate gland.[52][53]

Monotremes and marsupial moles lack prostates, instead having simpler cloacal glands that carry their function.[54][55]

In invertebrates

A prostate gland also occurs in some invertebrate species, such as gastropods.[56]

Additional images

-

Urinary bladder

-

Structure of the penis

-

Lobes of prostate

-

Zones of prostate

-

Prostate

-

Microscopic glands of the prostate

-

Male Anatomy

-

The deeper branches of the internal pudendal artery.

-

Lymphatics of the prostate.

-

Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculæ seminales.

-

Vesiculae seminales and ampullae of ductus deferentes, front view.

-

Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra.

-

Dissection of prostate showing prostatic urethra.

See also

- Glossary

References

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Prostate". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^ Tsukise, A.; Yamada, K. (1984). "Complex carbohydrates in the secretory epithelium of the goat prostate". The Histochemical Journal. 16 (3): 311–9. doi:10.1007/BF01003614. PMID 6698810.

- ^ "Chemical composition of human semen and of the secretions of the prostate and seminal vehicles". Am J Physiol. 136 (3): 467–473. 1942.

- ^ "Semen analysis". www.umc.sunysb.edu. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- ^ Leissner KH, Tisell LE (1979). "The weight of the human prostate". Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 13 (2): 137–42. doi:10.3109/00365597909181168. PMID 90380.

- ^ a b Fowke JH, Motley SS, Cookson MS, Concepcion R, Chang SS, Wills ML, Smith-Jr JA (December 19, 2006). "The association between body size, prostate volume and prostate-specific antigen". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 10 (2): 137–142. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500924. PMID 17179979. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Prostate Gland Development". ana.ed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2003-04-30. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ^ "The Prostate". Gray's Anatomy. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ^ "Instant Anatomy – Abdomen – Vessels – Veins – Prostatic plexus". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, B.; Cahill, D. (2008). "Pelvic fasciae in urology". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 90 (8): 633–637. doi:10.1308/003588408X321611. PMC 2727803. PMID 18828961.

- ^ Myers, Robert P (2000). "Structure of the adult prostate from a clinician's standpoint". Clinical Anatomy. 13 (3): 214–5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:3<214::AID-CA10>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 10797630.

- ^ a b "Basic Principles: Prostate Anatomy". Urology Match. Www.urologymatch.com. Web. 14 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Prostate Cancer Information from the Foundation of the Prostate Gland." Prostate Cancer Treatment Guide. Web. 14 June 2010.

- ^ Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, Phillips M, Moorin RE, Wheeler TM, Garrett KL (2008). "Central zone carcinoma of the prostate gland: a distinct tumor type with poor prognostic features". The Journal of Urology. 179 (5): 1762–7, discussion 1767. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.017. PMID 18343454.

- ^ Moore, Keith L.; Persaud, T. V. N.; Torchia, Mark G. (2008). Before We are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects (7th ed.). ISBN 978-1-4160-3705-7.

- ^ Template:En icon Gevaert, T; Lerut, E; Joniau, S; Franken, J; Roskams, T; De Ridder, D (2014). "Characterization of subepithelial interstitial cells in normal and pathologic human prostate". Histopathology. 65 (3): 418–28. doi:10.1111/his.12402. PMID 24571575.

- ^ "The male hot spot — Massaging the prostate". Go Ask Alice!. 2002-09-27 [Last Updated/Reviewed on 2008-03-28]. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-0618755714. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Komisaruk, Barry R.; Whipple, Beverly; Nasserzadeh, Sara; Beyer-Flores, Carlos (2009). The Orgasm Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Alan J., Wein; Louis R., Kavoussi; Alan W., Partin; Craig A., Peters (23 October 2015). Campbell-Walsh Urology (Eleventh ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1005–. ISBN 9780323263740.

- ^ "The human proteome in prostate - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ^ Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900.

- ^ O'Hurley, Gillian; Busch, Christer; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Stadler, Charlotte; Tolf, Anna; Lundberg, Emma; Schwenk, Jochen M.; Jirström, Karin (2015-08-03). "Analysis of the Human Prostate-Specific Proteome Defined by Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Profiling Identifies TMEM79 and ACOXL as Two Putative, Diagnostic Markers in Prostate Cancer". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0133449. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133449. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4523174. PMID 26237329.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Physical Therapy Treatment for Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ "Quercetin Treatment for Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan CA (2006). "Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training". J. Urol. 176 (4 Pt 1): 1534–8, discussion 1538–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.383.7495. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.010. PMID 16952676.

- ^ Verhamme KM; Dieleman JP; Bleumink GS (2002). "Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care—the Triumph project". Eur. Urol. 42 (4): 323–8. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00354-8. PMID 12361895.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Christensen, TL; Andriole, GL (February 2009). "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current Treatment Strategies". Consultant. 49 (2).

- ^ Dineen MK, Shore ND, Lumerman JH, Saslawsky MJ, Corica AP (2008). "Use of a Temporary Prostatic Stent After Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy Reduced Voiding Symptoms and Bother Without Exacerbating Irritative Symptoms". J. Urol. 71 (5): 873–877. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.015. PMID 18374395.

- ^ "Slide 33: Prostate, at ouhsc.edu".

- ^ Kristal AR; Arnold KB; Schenk JM (2008). "Dietary patterns, supplement use, and the risk of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial". Am. J. Epidemiol. 167 (8): 925–34. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm389. PMID 18263602.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ de Jong, Y; Pinckaers, JH; Ten Brinck, RM; Lycklama À Nijeholt, AA; Dekkers, OM (2014). "Urinating Standing versus Sitting: Position Is of Influence in Men with Prostate Enlargement. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLoS ONE. 9 (7): e101320. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320. PMC 4106761. PMID 25051345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Watchful Waiting Advised .Some Prostate Patients Benefit". The Daily Courier. Aug 23, 1995. p. 4. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ American Cancer Society American Cancer Society Guidelines for the early detection of cancer Cited: September 2011. Cancer.org. Retrieved on 2013-01-21.

- ^ Morgan, R.; Boxall, A.; Bhatt, A.; Bailey, M.; Hindley, R.; Langley, S.; Whitaker, H. C.; Neal, D. E.; Ismail, M. (2011). "Engrailed-2 (EN2): A Tumor Specific Urinary Biomarker for the Early Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (5): 1090–8. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2410. PMID 21364037.

- ^ New prostate cancer twice as effective as a PSA test could be available by next year. medicinechest.co.uk (2 March 2011)

- ^ "Defeating Prostate Cancer: Crucial Directions for Research" (PDF). National Cancer Institute. August 1998. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Olsen, Bruce D. (2009-05-09). Understanding Human Anatomy Through Evolution (Second ed.). p. 112. ISBN 9780578021645.

- ^ Australian Mammal Society (December 1978). Australian Mammal Society. Australian Mammal Society.

- ^ Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe; Marilyn Renfree (30 January 1987). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- ^ C. Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe (2005). Life of Marsupials. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-06257-3.

- ^ Sherwood, Lauralee; Klandorf, Hillar; Yancey, Paul (January 2012). Animal Physiology: From Genes to Organisms. p. 779. ISBN 9781133709510.

- ^ Nelsen, O. E. (1953) Comparative embryology of the vertebrates Blakiston, page 31.

- ^ Glover, Tim (2012-07-12). Mating Males: An Evolutionary Perspective on Mammalian Reproduction. p. 31. ISBN 9781107000018.

- ^ Animal reproductive system Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Asdell S A (1965) "Reproduction and Development" In: William Mayer (Ed) Physiological Mammalogy, Volume 2, page 9. Elsevier. ISBN 9780323155250.

- ^ William F. Perrin; Bernd Würsig; J.G.M. Thewissen (26 February 2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- ^ Rommel, Sentiel A., D. Ann Pabst, and William A. McLellan. "Functional anatomy of the cetacean reproductive system, with comparisons to the domestic dog." Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea. Science Publishers (2016): 127-145.

- ^ Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. p. 90. ISBN 9780199230846.

- ^ Zaviačič, Milan (1999). The Human Female Prostate: From Vestigial Skene's Paraurethral Glands and Ducts to Woman's Functional Prostate. ISBN 9788088908500.

- ^ Santos, F C A; Taboga, S R (2006). "Female prostate: a review about the biological repercussions of this gland in humans and rodents" (PDF). Animal Reproduction. 3 (1): 3–18.

- ^ Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction. 2005-12-12. p. 1165. ISBN 9780080535272.

- ^ Cope, E. D. (1892). "On the Habits and Affinities of the New Australian Mammal, Notoryctes typhlops". The American Naturalist. 26 (302): 121–128. JSTOR 2452234.

- ^ Riedelsheimer, B.; Unterberger, Pia; Künzle, H.; Welsch, U. (2007). "Histological study of the cloacal region and associated structures in the hedgehog tenrec Echinops telfairi". Mammalian Biology - Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 72 (6): 330–341. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2006.10.012.

- ^ Barth, Robert; Broshears, Robert (1982). The Mollusks. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders College Publishing.

Sources

- Portions of the text of this article originate from NIH Publication No. 02-4806, a public domain resource. "What I need to know about Prostate Problems". 2002-06-01. Archived from the original on 2002-06-01. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

External links

Media related to Prostate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prostate at Wikimedia Commons- Prostate at the Human Protein Atlas