Prostitution in ancient Rome

Prostitution in ancient Rome was legal and licensed. In ancient Rome, even Roman men of the highest social status were free to engage prostitutes of either sex without incurring moral disapproval,[1] as long as they demonstrated self-control and moderation in the frequency and enjoyment of sex. At the same time, the prostitutes themselves were considered shameful: most were either slaves or former slaves, or if free by birth relegated to the infames, people utterly lacking in social standing and deprived of most protections accorded to citizens under Roman law, a status they shared with actors and gladiators, all of whom, however, exerted sexual allure.[2] Some large brothels in the 4th century, when Rome was becoming officially Christianized, seem to have been counted as tourist attractions and were possibly state-owned.[3]

Most prostitutes were slaves or freedwomen, and it is difficult to determine the balance of voluntary to forced prostitution. Because slaves were considered property under Roman law, it was legal for an owner to employ them as prostitutes.[4] The 1st-century historian Valerius Maximus presents a story of complicated sexual psychology in which a freedman had been forced by his owner to prostitute himself during his time as a slave; the freedman kills his own young daughter when she loses her virginity to her tutor.[5][6]

Although rape was a crime in ancient Rome, the law only punished the rape of a slave if it "damaged the goods", since a slave had no legal standing as a person. The penalty was aimed at providing the owner compensation for the "damage" of his property.

Sometimes the seller of a female slave attached a ne serva clause to the ownership papers to prevent her from being prostituted. The ne serva clause meant that if the new owner or any owner afterwards used the slave as a prostitute she would be free.[7]

A law of Augustus allowed that women guilty of adultery could be sentenced to forced prostitution in brothels. The law was abolished in 389.[8]

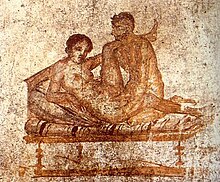

Latin literature makes frequent reference to prostitutes. Historians such as Livy and Tacitus mention prostitutes who had acquired some degree of respectability through patriotic, law-biding, or euergetic behavior. The high-class "call girl" (meretrix) is a stock character in Plautus's comedies, which were influenced by Greek models. The poems of Catullus, Horace, Ovid, Martial, and Juvenal, as well the Satyricon of Petronius, offer fictional or satiric glimpses of prostitutes. Real-world practices are documented by provisions of Roman law that regulate prostitution, and by inscriptions, especially graffiti from Pompeii. Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum from sites presumed to be brothels has also contributed to scholarly views on prostitution.

The prostitutes

A meretrix (plural: meretrices) was registered female prostitute; a higher class—the more pejorative scortum could be used for prostitutes of either gender. Unregistered or casual prostitutes fell under the broad category prostibulae, lower class.[9] Although both women and men might engage male or female prostitutes, evidence for female prostitution is the more ample.[10]

There is some evidence that slave prostitutes could benefit from their labor;[11] in general, slaves could earn their own money by hiring out their skills or taking a profit from conducting their owner's business.

A prostitute could be self-employed and rent a room for work. A girl (puella, a term used in poetry as a synonym for "girlfriend" or meretrix and not necessarily an age designation) might live with a procuress or madame (lena) or even go into business under the management of her mother,[1] though mater might sometimes be a mere euphemism for lena.[citation needed] These arrangements suggest the recourse to prostitution by free-born women in dire financial need, and such prostitutes may have been regarded as of relatively higher repute or social degree.[1] Prostitutes could also work out of a brothel or tavern for a procurer or pimp (leno). Most prostitutes seem to have been slaves or former slaves.[1]

In Roman law, the status of meretrices was specifically and closely regulated.[12] They were obliged to register with the aediles,[13] and (from Caligula's day onwards) to pay imperial tax.[14] They were regarded as "infamous persons" and were denied many of the civic rights due to citizens. They could not give evidence in court,[14] and Roman freeborn men were forbidden to marry them.[15] There were, however, degrees of infamia and the consequent loss of privilege attendant on sexual misbehaviour. A convicted adulteress of citizen status who registered herself as a meretrix could thus as least partly mitigate her loss of rights and status.[16]

Some professional prostitutes, perhaps to be compared to courtesans, cultivated elite patrons and could become wealthy. The dictator Sulla is supposed to have built his fortune on the wealth left to him by a prostitute in her will.[1] Romans also assumed that actors and dancers were available to provide paid sexual services, and courtesans whose names survive in the historical record are sometimes indistinguishable from actresses and other performers.[1] In the time of Cicero, the courtesan Cytheris was a welcome guest for dinner parties at the highest level of Roman society. Charming, artistic, and educated, such women contributed to a new romantic standard for male-female relationships that Ovid and other Augustan poets articulated in their erotic elegies.[17]

Clothing and appearance

From the late Republican or early Imperial era onwards, meretices may have worn the toga when in public, through compulsion or choice. The possible reasons for this remain a subject of modern scholarly speculation. Togas were otherwise the formal attire of citizen men, while respectable adult freeborn women and matrons wore the stola. This crossing of gender boundaries has been interpreted variously. At the very least, the wearing of a toga would have served to set the meretrix apart from respectable women, and suggest her sexual availability;[18] Bright colors – "Colores meretricii" – and jewelled anklets also marked them out from respectable women.[19]

In Pompeii, there have been artifacts found that may suggest some sexually enslaved peoples may have worn jewelry gifted to them by their masters.[20]

Expensive courtesans wore gaudy garments of see-through silk.[21]

Some passages in Roman authors seem to indicate that prostitutes displayed themselves in the nude. Nudity was associated with slavery, as an indication that the person was literally stripped of privacy and the ownership of one's own body.[22] A passage from Seneca describes the condition of the prostitute as a slave for sale:

Naked she stood on the shore, at the pleasure of the purchaser; every part of her body was examined and felt. Would you hear the result of the sale? The pirate sold; the pimp bought, that he might employ her as a prostitute.[23]

In the Satyricon, Petronius's narrator relates how he "saw some men prowling stealthily between the rows of name-boards and naked prostitutes".[24] The satirist Juvenal describes a prostitute as standing naked "with gilded nipples" at the entrance to her cell.[25] The adjective nudus, however, can also mean "exposed" or stripped of one's outer clothing, and the erotic wall paintings of Pompeii and Herculaneum show women presumed to be prostitutes wearing the Roman equivalent of a bra even while actively engaged in sex acts.

Regulation

Prostitution was regulated to some extent, not so much for moral reasons as to maximize profit.[26] Prostitutes had to register with the aediles.[21] She gave her correct name, her age, place of birth, and the pseudonym under which she intended practicing her calling.[27] If the girl was young and apparently respectable, the official sought to influence her to change her mind;[citation needed] failing in this, he issued her a "license for debauchery" (licentia stupri), ascertained the price she intended exacting for her favors, and entered her name in his roll. Once entered there, the name could never be removed, but must remain for all time, an insurmountable bar to repentance and respectability.

Caligula inaugurated a tax upon prostitutes (the vectigal ex capturis), as a state impost: "he levied new and hitherto unheard of taxes; a proportion of the fees of prostitutes;—so much as each earned with one man. A clause was also added to the law directing that women who had practiced prostitutery and men who had practiced procuration should be rated publicly; and furthermore, that marriages should be liable to the rate".[28] Alexander Severus retained this law, but directed that such revenue be used for the upkeep of the public buildings, that it might not contaminate the state treasure.[29] This infamous tax was not abolished until the time of Theodosius I, but the real credit is due to a wealthy patrician named Florentius, who strongly censured this practice, to the Emperor, and offered his own property to make good the deficit which would appear upon its abrogation.[30]

Brothels

Roman brothels are known from literary sources, regionary lists, and archaeological evidence. A brothel is commonly called a lupanar or lupanarium, from lupa, "she-wolf", slang[31] for "prostitute," or fornix, a general term for a vaulted space or cellar. According to the regionaries for the city of Rome,[32] lupanaria were concentrated in Regio II;[33] the Caelian Hill, the Suburra that bordered the city walls, and the valley between the Caelian and Esquiline Hills.

The Great Market (macellum magnum) was in this district, along with many cook-shops, stalls, barber shops, the office of the public executioner, and the barracks for foreign soldiers quartered at Rome. Regio II was one of the busiest and most densely populated quarters in the entire city — an ideal location for the brothel owner or pimp. Rent from a brothel was a legitimate source of income.[34]

The regular brothels are described as exceedingly dirty, smelling of characteristic odors lingering in poorly ventilated spaces and of the smoke from burning lamps, as noted accusingly by Seneca: "you reek still of the soot of the brothel".[35]

Some brothels aspired to a loftier clientele. Hair dressers were on hand to repair the ravages wrought by frequent amorous conflicts, and water boys (aquarioli) waited by the door with bowls for washing up.

The licensed houses seem to have been of two kinds: those owned and managed by a pimp (leno) or madam (lena), and those in which the latter was merely an agent, renting rooms and acting as a supplier for his renters. In the former, the owner kept a secretary, villicus puellarum, or an overseer for the girls. This manager assigned a girl her name, fixed her prices, received the money and provided clothing and other necessities.[36] It was also the duty of the villicus, or cashier, to keep an account of what each girl earned: "give me the brothel-keeper's accounts, the fee will suit".[37]

The mural decoration was also in keeping with the object for which the house was maintained; see erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Over the door of each cubicle was a tablet (titulus) upon which was the name of the occupant and her price; the reverse bore the word occupata ("occupied, in service, busy") and when the inmate was engaged the tablet was turned so that this word was out. Plautus[38] speaks of a less pretentious house when he says: "let her write on the door that she is occupata". The cubicle usually contained a lamp of bronze or, in the lower dens, of clay, a pallet or cot of some sort, over which was spread a blanket or patch-work quilt, this latter being sometimes employed as a curtain.[24] The fees recorded at Pompeii range from 2 to 20 asses per client.[1] By comparison, a legionary earned around 10 asses per day (225 denarii per year), and an as could buy 324 g of bread. Some brothels may have had their own token coin system, called spintria.

Because intercourse with a meretrix was almost normative for the adolescent male of the period, and permitted for the married man as long as the prostitute was properly registered,[39] brothels were commonly dispersed around Roman cities, often found between houses of respected families.[40] These included both large brothels and one-room cellae meretriciae, or "prostitute's cots".[41] Roman authors often made distinctions between "good faith" meretrices who truly loved their clients, and "bad faith" prostitutes, who only lured them in for their money.[42][43]

Other locations

The arches under the circus were a favorite location for prostitutes or potential prostitutes. These arcade dens were called "fornices", from which derives the English word fornication.[citation needed] The taverns, inns, lodging houses, cook shops, bakeries, spelt-mills and like institutions all played a prominent part in the underworld of Rome.

The taverns were generally regarded by the magistrates as brothels and the waitresses were so regarded by the law.[44] The poem "The Barmaid" ("Copa"), attributed to Virgil, proves that even the proprietress had two strings to her bow, and Horace,[45] in describing his excursion to Brundisium, narrates his experience, or lack of it, with a waitress in an inn. This passage, it should be remarked, is the only one in all his works in which he is absolutely sincere in what he says of women. "Here like a triple fool I waited till midnight for a lying jade till sleep overcame me, intent on venery; in that filthy vision the dreams spot my night clothes and my belly, as I lie upon my back." In the Aeserman inscription[46] we have another example of the hospitality of these inns, and a dialogue between the hostess and a transient. The bill for the services of a girl amounted to 8 asses. This inscription is of great interest to the antiquary, and to the archeologist. That bakers were not slow in organizing the grist mills is shown by a passage from Paulus Diaconus:[47] "as time went on, the owners of these turned the public corn mills into pernicious frauds. For, as the mill stones were fixed in places under ground, they set up booths on either side of these chambers and caused prostitutes to stand for hire in them, so that by these means they deceived very many, some that came for bread, others that hastened thither for the base gratification of their wantonness." From a passage in Festus, it would seem that this was first put into practice in Campania: "prostitutes were called 'aelicariae', 'spelt-mill girls, in Campania, being accustomed to ply for gain before the mills of the spelt-millers". "Common strumpets, bakers' mistresses, refuse the spelt-mill girls," says Plautus.[48]

Prostitution and religion

Prostitutes had a role in several ancient Roman religious observances, mainly in the month of April. On 1 April, women honored Fortuna Virilis, "Masculine Luck", on the day of the Veneralia, a festival of Venus. According to Ovid,[50] prostitutes joined married women (matronae) in the ritual cleansing and reclothing of the cult statue of Fortuna Virilis.[51] Usually, the line between respectable women and the infames was carefully drawn: when a priestess traveled through the streets, attendants moved prostitutes along with other "impurities" out of her path.[52]

On 23 April, prostitutes made offerings at the Temple of Venus Erycina that had been dedicated on that date in 181 BC, as the second temple in Rome to Venus Erycina (Venus of Eryx), a goddess associated with prostitutes. The date coincided with the Vinalia, a wine festival.[51] "Pimped-out boys" (pueri lenonii) were celebrated on 25 April, the same day as the Robigalia, an archaic agricultural festival aimed at protecting the grain crops.[53]

On 27 April, the Floralia, held in honor of the goddess Flora and first introduced about 238 BC, featured erotic dancing and stripping by women characterized as prostitutes. According to the Christian writer Lactantius, "in addition to the freedom of speech that pours forth every obscenity, the prostitutes, at the importunities of the rabble, strip off their clothing and act as mimes in full view of the crowd, and this they continue until full satiety comes to the shameless lookers-on, holding their attention with their wriggling buttocks".[54] Juvenal also refers to the nude dancing, and perhaps to prostitutes fighting in gladiatorial contests.[55]

Medieval meretrix

In Medieval Europe, a meretrix was understood as any woman held in common, who “turned no one away”.[56] It was generally understood that money would be involved in this transaction, but it did not have to be: rather, it was promiscuousness that defined the meretrix.[57]

Medieval Christian authors often discouraged prostitution, but did not consider it a serious offence and under some circumstances even considered marrying a harlot to be an act of piety.[58] Every woman was considered to contain a latent meretrix, so that it was possible to both rise out of and fall into the category, as with tales of prostitutes repenting to become saints.[59]

Certain modern professors of feminism have argued that a meretrix in the medieval mindset is closer to our modern understanding of a sexual identity or orientation.[60]

See also

- History of prostitution

- Infamia

- Petronius Arbiter

- Propertius

- Prostitution in ancient Greece

- Sexuality in ancient Rome

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Dillon & Garland 2005, p. 382.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 66-.

- ^ McGinn 2004, pp. 167–168.

- ^ McGinn 1998, p. 56.

- ^ Valerius Maximus 6.1.6

- ^ Richlin, Amy (1993). "Not before Homosexuality: The Materiality of the Cinaedus and the Roman Law against Love between Men". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 3 (4): 523–73. JSTOR 3704392.

- ^ McGinn 1998, p. 293.

- ^ McGinn 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Adams, J. N., Words for "prostitute" in Latin, University of Koeln, 1983, pp. 325 - 358 [1]

- ^ McGinn 2004, p. 2.

- ^ McGinn 2004, p. 52.

- ^ Sokala 1998, pp. 5–35.

- ^ Balsdon 1963, p. 227.

- ^ a b H. Nettleship/J. E. Sandys eds., A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1894) p. 293

- ^ Balsdon 1963, p. 192.

- ^ Adams, J. N., Words for "prostitute" in Latin, University of Koeln, 1983, p. 342

- ^ R.I. Frank, "Augustan Elegy and Catonism," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.30.1 (1982), p. 569.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Balsdon 1963, pp. 224, 252-4 and p. 327n.

- ^ Baird, J. A. (2015). "On Reading the Material Culture of Ancient Sexual Labor". Helios. 42 (1): 163–175. doi:10.1353/hel.2015.0001. ISSN 1935-0228.

- ^ a b Edwards 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Alastair J. L. Blanshard, Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 24.

- ^ Seneca, Controv. lib. i, 2. Horace dwells at length on the inspection of female flesh: "The matron has no softer thigh nor has she a more beautiful leg, though the setting be one of pearls and emeralds (with all due respect to thy opinion, Cerinthus), the togaed plebeian's is often the finer, and, in addition, the beauties of figure are not camouflaged; that which is for sale, if honest, is shown openly, whereas deformity seeks concealment. It is the custom among kings that, when buying horses, they inspect them in the open, lest, as is often the case, a beautiful head is sustained by a tender hoof and the eager purchaser may be seduced by shapely hocks, a short head, or an arching neck. Are these experts right in this? Thou canst appraise a figure with the eyes of Lynceus and discover its beauties; though blinder than Hypoesea herself thou canst see what deformities there are. Ah, what a leg! What arms! But how thin her buttocks are, in very truth what a huge nose she has, she's short-waisted, too, and her feet are out of proportion! Of the matron, except for the face, nothing is open to your scrutiny unless she is a Catia who has dispensed with her clothing so that she may be felt all over thoroughly, the rest will be hidden. But as for the other, no difficulty there! Through the Coan silk it is as easy for you to see as if she were naked, whether she has an unshapely leg, whether her foot is ugly; her waist you can examine with your eyes" (Satire I, ii).

- ^ a b Petronius 2009, chap. 7.

- ^ Juvenal, Satire vi, 121 et seq.

- ^ McGinn 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Plautus, Poenulus[citation needed]

- ^ Suetonius, Calig. xi.

- ^ Lamprid. Alex. Severus, chap. 24.

- ^ Ovid 2003, p. 318, note.

- ^ McGinn 2004, pp. 7–8.

- ^ The two extant regionaries for the city of Rome enumerate landmarks, temples, attractions, public facilities, and private buildings in each of the city's 14 regions in the mid-4th century. See Curiosum Urbis and Notitia Notitia de Regionibus at LacusCurtius by Bill Thayer

- ^ Adler, Description of the City of Rome, pp. 144 et seq.

- ^ Ulpian, Law as to Female Slaves Making Claim to Heirship.[citation needed]

- ^ Seneca, Cont. i, 2. See also Horace, Satire i, 2, 30 ("on the other hand, another will have none at all except she be standing in the evil-smelling cell" of the brothel); Petronius, Satyricon" xxii ("worn out by all his troubles, Ascyltos commenced to nod, and the maid, whom he had slighted, and, of course, insulted, smeared lamp-black all over his face"); Priapeia xiii, 9 ("whoever likes may enter here, smeared with the black soot of the brothel").

- ^ Seneca, Controv. i, 2: "you stood with the prostitutes, you stood decked out to please the public, wearing the costume the pimp had furnished you."

- ^ Seneca, Controv. lib. i, 2.

- ^ Plautus, Asin. iv, i, 9.

- ^ Balsdon 1963, pp. 218 and 225-6.

- ^ Duncan 2006, p. 13.

- ^ McGinn 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Duncan 2006, p. 259.

- ^ Duckworth 1994, p. 253.

- ^ Codex Theodos. lx, tit. 7, ed. Ritter; Ulpian liiii, 23, De Ritu Nupt.

- ^ Horace, Sat. lib. i, v, 82.

- ^ Mommsen, Inscr. Regn. Neap. 5078, which is number 7306 in Orelli-Henzen.

- ^ Paulus Diaconus, xiii, 2.

- ^ Plautus, i, ii, 54.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti 4, as discussed by T.P. Wiseman, The Myths of Rome (University of Exeter Press, 2004), pp. 1–11.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti 4.133–134.

- ^ a b Culham 2004, p. 144.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 82.

- ^ According to the Fasti Praenestini; Craig A. Williams, Roman Homosexuality (Oxford University Press, 1999, 2010), p. 32.

- ^ Lactantius, Instit. Divin. 20.6.

- ^ Juvenal, Satire 6.250–251, as cited by Culham, "Women in the Roman Republic," p. 144.

- ^ Biffi 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Phillips & Reay (2002), p. 93.

- ^ Brundage 1990, p. 308.

- ^ Carla Freccero, Queer/Early/Modern (2005) p. 37

- ^ Martha C. Nussbaum/Juha Sivola, The Sleep of Reason (2002) p. 247-8

Bibliography

- Balsdon, John Percy Vyvian Dacre (1963), Roman Women. Their History and Habits, J. Day

- Biffi, Giacomo (2000), Casta meretrix: "the chaste whore" : an essay on the ecclesiology of St. Ambrose, Saint Austin Press, ISBN 978-1-901157-34-5

- Brundage, James A. (1990), "Prostitution", Law, sex, and Christian society in medieval Europe, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-07784-0

- Culham, Phyllis (2004), "Women in the Roman Republic", in Flower, Harriet I. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781107669420

- Dillon, Matthew; Garland, Lynda (2005), Ancient Rome: From the Early Republic to the Assassination of Julius Caesar, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780415224581

- Duckworth, George Eckel (1994), The nature of Roman comedy: a study in popular entertainment, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0-8061-2620-3

- Duncan, Anne (2006), "Infamous performers : comic actors and female prostitutes in Rome", in Faraone, Christopher A.; McClure, Laura (eds.), Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World, Wisconsin studies in classics, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-21314-5

- Edwards, Catherine (1997), "Unspeakable Professions Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome", in Hallett, Judith P.; Skinner, Marilyn B. (eds.), Roman Sexualities, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691011788

- McGinn, Thomas A. J. (1998), Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195161328

- McGinn, Thomas A. (2004), The economy of prostitution in the Roman world: a study of social history & the brothel, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-11362-0

- Ovid (2003), Gibson, Roy K. (ed.), Ars Amatoria, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-81370-9

- Petronius (2009), The Satyricon, OUP Oxford, ISBN 9780199539215

- Phillips, Kim M.; Reay, Barry (2002), Sexualities in History: A Reader, Routledge, ISBN 9780415929356

- Sokala, Andrzej (1998), Meretrix i jej pozycja w prawie rzymskim (in Polish), Nicolaus Copernicus University Press, ISBN 978-83-231-0995-2