Pyramid of Neferefre

| Pyramid of Neferefre | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neferefre | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 29°53′38″N 31°12′6″E / 29.89389°N 31.20167°E | ||||||||||||||

| Ancient name |

Nṯr.j-b3w-nfr-f-Rˁ[2] Netjeri-bau-Nefer-ef-Ra "Divine are the Ba's of Neferefre"[3] Alternatively translated as "Divine is Neferefre's power"[4] | ||||||||||||||

| Constructed | Fifth Dynasty (2460 – 2455 BC)[5] | ||||||||||||||

| Type | True pyramid (intended) Square mastaba (converted) | ||||||||||||||

| Material | Limestone | ||||||||||||||

| Height | ~7 metres (23 ft)[6] | ||||||||||||||

| Base | 65 metres (213 ft 3 in)[7] | ||||||||||||||

| Slope | 78° (after Mastaba conversion) [8] | ||||||||||||||

The Pyramid of Neferefre, also known as the Pyramid of Raneferef, is an unfinished Egyptian pyramid from the Fifth Dynasty, located in the necropolis of Abusir, Egypt. After the early death of Pharaoh Neferefre, the unfinished building was reconstructed into a geometric mastaba, becoming the burial place of the deceased king. Despite the demolition of the actual pyramid, the complex was augmented through extensive construction of temples by Neferefre's successors.[9][10]

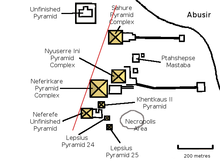

The pyramid was initially ignored by egyptologists. The first assignment was made by Karl Richard Lepsius, who called it Lepsius XXVI, but a definitive research was established in 1974 by the Czech team of Charles University in Prague under Miroslav Verner. Items as papyri and statues were discovered consisting of important information about the short-ruling Neferefre. Known as nTri bAw nfrf ra ("Divine is Neferefre's Power"), the complex is located directly south-west of the Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai and west of the Pyramid of Khentkaus II, and situated at the southern end of the necropolis, becoming the farthest into the desert of all pyramids of Abusir. With a base length of 65 metres (213 ft) it could have been the second-smallest king pyramid in the Old Kingdom of Egypt after the Pyramid of Unas. Apart from the actual pyramid, the complex includes the mortuary temple, the "Sanctuary of the Knife" and the sun sanctuary. The complex is surrounded by a large circular wall.

Location and excavation

Early surveys

The unfinished pyramid is located to the south-west of Neferirkare's pyramid[11][12] in the Abusir necropolis.[1] It is seated on the Abusir diagonal,[7] a figurative line touching the north-western corners of the three pyramids of Sahure, Neferirkare, and Neferefre, and pointing towards Heliopolis. It is similar to the Giza axis which converges to the same point, however, the Giza pyramids are linked at their south-east corners instead.[11] Simultaneously, this location gives an indication of its position on a chronological scale. As the third in line on the Abusir diagonal, it follows that it must be the third in line of succession after Sahure and Neferirkare. This is further corroborated by another feature of its location. It is the furthest of the three from the Nile delta, and thus holds the least advantageous location for transporting materials.[13]

The building was first noticed during the early archaeological studies of the necropolis of Abusir, but was not examined intensively. John Shae Perring (1835–1837),[14] and later Karl Richard Lepsius (1842–1846),[14] Jacques de Morgan and Ludwig Borchardt gave limited attention to the building.[1] Lepsius categorized the ruins under the name of Lepsius XXVI in his pyramid list.[15]

Borchardt's trial excavations

The German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt carried out "trial digging" at the site. He dug a trench into the open ditch that spanned from the north face of the monument to its center. Borchardt anticipated that if the monument had been functional, that he would encounter the passage leading into the burial chamber. The experiment failed, and Borchardt concluded that the structure was never completed or made functional.[16] Egyptologist Miroslav Verner explains: The substructure passage had a north-south orientation with the passage pointing to the Polestar. The Egyptians believed that the pharaoh would join Re in the sky and remain in the "heavenly ocean" for all eternity. By contrast the burial- and ante- chambers were oriented east-west, and the mummy itself was placed against the western wall with its head pointed north, but facing east. Either by chance or error, Borchardt gave up, while only a metre away from making the archaeological discovery, after failing to find the passage to the- or even the- substructure. As a result of Borchardt's decision, the identity of the monument remained unknown for another seventy years.[17]

Charles University excavations and discoveries

A definitive assignment of an owner to the pyramid stump was not possible prior to the 1970s. Some researchers attributed it to Neferefre, others to the ephemeral Shepseskare, and others still left the question of the authorship open. At the time it was unanimously agreed upon that the structure was abandoned before its completion, excluding the possibility of a burial and, consequently, a funerary cult.[18] An intensive research of the remains began in 1974,[7] by the Czech team of Charles University in Prague.[13][19] The owner of the monument was identified based on the discovery of a single cursive inscription containing Neferefre's name, written in black on a block taken from the core of the pyramid.[20] The archaeological excavations of the Czech team continued throughout the 1980s.[20]

The pyramid's location also gives an indication of its position on a chronological scale. As the third in line on the Abusir diagonal, it follows that it must be the third in line of succession after Sahure and Neferirkare. This is further corroborated by another feature of its location. It is the furthest of the three from the Nile delta, and thus holds the least advantageous location for transporting materials.[13] One more significant piece in the chronological puzzle was the discovery of a limestone block in the village of Abusir.[11][21] The block, discovered by Egyptologist Édouard Ghazouli in the 1930s, depicts Neferirkare with his consort, Khentkaus II, and eldest son, Neferefre.[21]

Few remnants of the burial could be recovered from the burial chamber owing to the devastation caused by stone quarrying over the centuries. Among the scraps were some pieces of burial equipment, fragments of a pink granite sarcophagus, and the remnants of a mummy. Preliminary anatomical investigations of the mummy remnants indicate that they belong to a man who died in his early twenties: twenty to twenty–three years of age.[22] The combination of archaeological and anatomical evidence indicates that Neferefre is the almost certain owner of the pyramid.[23]

A clay seal bearing Shepseskare's Horus name was discovered in Neferefre's mortuary temple during the Czech team's excavations.[24] This discovery has prompted a number of theories concerning the rule of Shepseskare. If the seal indicates that Shepseskare initiated the improvised completion of Neferefre's tomb, then Shepseskare was his immediate successor and not Nyuserre. Another speculative suggestion concerns the unfinished pyramid located on the northern outskirts of the Abusir necropolis and whether it may belong to Shepseskare.[25]

Building conditions

Neferefre began his short rule with the construction of the pyramid complex, the nTri bAw nfrf ra (Divine is Neferefre's Power), in the necropolis of Abusir, directly south-west of the Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai and west of the pyramid of Khentkaus II. The pyramid is situated at the southern end of the necropolis and is the farthest into the desert of all pyramids of Abusir.

The premature death of the king after a reign of only five years (from 2460 to 2455 BC)[5] led to the demolition of the construction works and to hasty conversion of the complex into a burial and cult ground in the shape of a square mastaba. His successors completed the cult places and the complex, but not the pyramid. According to papyri in the temple, the pyramid is a "hill".[26]

Plunderings and stone robberies

The building was looted and damaged by stone robbery, common for pyramid complexes. The unfinished form with the flat roof offered looters a simple entry, as they could dig into the substructure from its easily accessible top. The stone robbery and the lootings were apparently professionally organized, as residues were found of a workshop in the pyramid. This phenomenon possibly began as early as the First Intermediate Period and stone theft followed in the late New Kingdom, the Late Period, the reign by the Roman Empire and the Arabic Middle Ages right through the 19th century. Materials stolen from the pyramid complex could be found in nearby shaft tombs.[9] The temple area remained comparatively unaffected, as it was mainly composed of less valuable adobes.[10]

Pyramid

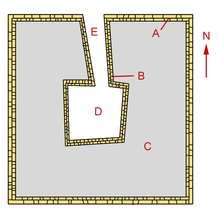

A: External wall

B: Internal wall

C: Stepping fill

D: Pit for the underground chambers

E: Pit for entry

The Pyramid of Neferefre was started with a base length of 65 metres (213 ft) and thus could have been the second-smallest king pyramid in the Old Kingdom of Egypt after the Pyramid of Unas. The planned height and side tilt are unknown, as the casing stones were never attached. The pyramid should have received a stepped core, covered by fine Tura limestones, but construction did not continue above the first step.[10]

Structure

The pyramid of Neferefre shed new light on the pyramid construction techniques of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties.[7][27][28] With one level of construction completed,[6][7] and standing a meagre seven metres tall,[6] the unfinished pyramid allowed investigators to study the structure and construction of the tomb in detail.[8][27] In particular, the Czech team was interested in testing Lepsius' accretion layer hypothesis for the construction of Fifth and Sixth Dynasty pyramids.[8][27][29]

The accretion layer hypothesis was first proposed by Richard Lepsius[30] after he had explored the necropolis in 1843.[12] It was later further promulgated by Borchardt, who surveyed the Abusir pyramids between 1902-8[12] and discovered what he believed were accretion layers in the internal faces of some of the pyramids.[30] The accretion layer method of construction can be described thusly; (1) A solid limestone core is constructed.[29][30][31] (2) The core is expanded on all four sides in successive layers with small stone blocks – ranging in length up to two feet and five to fifteen feet in thickness.[30] (3) The masonry is laid at a 75° slant pointing towards the core.[29][30] (4) Finally, the outer casing of each layer is smoothed to give the surface a flat finish.[30] Verner simplifies this description by describing them as "layers of an onion".[29] Lepsius justified his hypothesis with the idea that it allowed the pharaoh to expand his tomb gradually over the course of his reign.[30] Professor Bonnie Sampsell argues that if this were the case, the length of the reign should correlate with the size of the pyramid such that the longest reigning pharaohs also had the tallest or largest pyramids. No such relationship appears to exist.[30]

Italian Egyptologists Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi conducted careful examinations of the structure of Fourth and Fifth Dynasty pyramids in the 1960s and 1970s. The well preserved remains of pyramids at Dashur and Giza complicated this task, however, wherever the interior structure presented an opportunity for examination they found that the blocks were laid horizontally; not on a slant. The two Egyptologists had the opportunity to study both Userkaf's and Sahure's pyramids, and in both cases they found similar horizontally laid courses of masonry. These observations led them to reject the accretion layer hypothesis.[32]

Verner's and the Czech's team's excavations in the 1980s offer the final word on the hypothesis.[28][30] Initially, the ground was levelled and bearings taken for the first layer of the pyramid.[20] Then the burial pit and descending corridor were dug out. Afterwards, construction on the pyramid superstructure began with the laying of a foundation composed of two layers of enormous limestone blocks.[4] The single completed step of the superstructure[33] is dissected into three parts: an exterior mantle, an inner core surrounding the pit of the burial chamber and descending corridor, and filling to bridge the gap.[4] The exterior mantle was constructed by laying five or six horizontal courses of large, roughly dressed, but, well laid, grey limestone blocks.[4][29][33] The blocks used were up to 5 m (16 ft 5 in) in length, laid into 1 m (3 ft 3 in) thick layers, and were bound together with clay and mortar.[4][29] Verner adds that the blocks at the corners of the structure were especially well bound.[4] The inner core framed the chamber and corridor and was built in a similar fashion, but, using smaller blocks.[4][28][29] Finally the gap between the mantle and core was filled with poor quality limestone, clay, mortar and sand.[28][29] Verner observes that if the pyramid had been constructed as Lepsius and Borchardt described, then underneath the clay and gravel casing of the roof terrace the excavators would have found stone masonry forming parallel layers resembling a square onion.[29] He concludes that the other pyramids of the Abusir site had most probably been constructed the same way.[4][29]

The interior of the steps was filled with gravel, sand and mud. This offered a considerable saving of labor compared to the large and more accurately hewn limestone cores of 4th Dynasty pyramids, but made the core very sensitive to erosion. In fact, this construction technique is responsible for the ruinous state of all Fifth and Sixth Dynasty pyramids.[34]

The death of the pharaoh led to a stop in the construction works and design alterations were made to use the building for the funeral. The first step, about 7 metres (23 ft) high, received a cladding from rough limestones with a side slope of 78°, similar to a mastaba. This was covered with a layer of clay, in which flints from the local desert were pressed. The term "hill" (iat), found in the Abusir Papyri, might be connected with the primary hill myth.[10][26]

Substructure

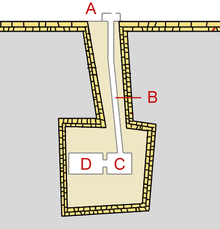

A: Entry with north chapel

B: Access passage

C: Antechamber

D: Burial chamber

The foundation of the pyramid was laid out in an open ditch. The ditch had an encircling wall, which extended to the first step of the pyramid and allowed simultaneous work on the foundation and the structure. The foundation was built in the same pattern as the Pyramid of Sahure. Access led from the north side of the pyramid downwards to the south direction and led to a slightly north-deviated horizontal passage. The lower area was faced with rose granite and had a portcullis slab barrier from the same material. Unusual and not verified in any other building was a further blocking device from jawlike, intertwined barriers in the centre of the horizontal passage. The burial chamber and the antechamber were, as usual, oriented east-to-west and faced with a pediment ceiling from fine limestone and a chamber cladding from the same material. Cladding, as well as pediment ceiling, were heavily damaged through stone robbery. Today, only single fragments of the foundation in the pit exist.[35]

Despite the devastation, the Czech group found the funerary goods and even the king's mummy, all in the substructure. In the burial chamber was a sarcophagus from rose granite, of which only a few fragments were preserved. Also found were fragments from the four canopic jars from alabaster and sacrifice jars from the same material.[36]

In all probability the mummified remains of the roughly 20- to 25-year-old ruler belong – according to analysis of the archeological circumstances of finding and the anthropological study – to Pharaoh Neferefre.[36]

Pyramid complex

A: Pyramid stump B: Interior temple C: Stack-room

D: Funery temple E: Entry of the temple

F: Gallery G: Sanctuary of the Knife H: Stockade

Elements such as the causeway, the valley temple and the cult pyramid are missing due to discontinuation of the building work upon the king's premature death. Only buildings which were important for the burial and funerary cult were accomplished by his successor, then, unusually, expanded by the latter's successor.[37]

Mortuary temple

Written evidence and the confident belief that the tomb belonged to a pharaoh precipitated the discovery of the mortuary temple of Neferefre's pyramid complex.[38] A magnetometric survey of the sand plain on the east side of the pyramid revealed a large, articulate, T-shaped[a] mudbrick building that was soon definitively identified as a mortuary temple.[11]

The small, possibly improvised temple on the east side of the pyramid was constructed in the first building phase of the mortuary temple. The limestone temple has a north-south orientation. A step ramp enables entry from the southeast. This temple had a mandatory offering hall as well as a room for the ritual purgation on the entry. Imprints of an altar were at that time verifiable. A false door was located on the west wall, which contained gold-plated inscriptions.[34] Offerings such as a bull head and sacrificial vessels were found below the paving of the temple. There might have been two boat pits at the temple for worship boats. No evidence was found in the remains for the builder, thus the direct successor of Neferefre is unknown. It is believed that short-ruling Shepseskare was the successor, as seal impressions of him were found in the area of the mortuary temple.[37][39]

The temple complex was heavily extended in the second phase under Pharaoh Niuserre. Compared to the initial temple, the building material was, with a few exceptions, mud brick. This new temple area also had a north-southern direction, but extended over the whole length of the east side of the truncated pyramid and encompassed the initial temple. The northern third of the new building contained two-storeyed storerooms. The middle part featured an entrance portico with two pillars and behind five oblong rooms, which are more reminiscent of storerooms than of the usual statue chapels. One chamber was later breached as an entry to the inner temple, while another chamber was sealed and incorporated the fire-damaged remnants of the two worship boats. The storage area also housed the temple archive, as there was no valley temple in this complex.[34] The southern temple area is only found in this pyramid complex. It had a large hall, surrounded by twenty wooden lotus pillars. The roof was decorated with golden stars on a dark-blue heaven. This area included fragments of ruler statues, worship items and wooden statuettes of prisoners of war.[37]

A third construction period also under Niuserre extended the temple to an eastern entry area and gave it the period's typical T-shaped arrangement. Here, the building material was also mainly mud brick. This expansion included a monumental entry decorated with two papyrus columns from limestone, an entry hall and a subsequent open column court with 22 wooden round columns.[37]

During the rule of Djedkare, the priests of the mortuary cult built simple brick accommodations in the column court. The ruler cult of Neferefre was performed until the end of the 6th Dynasty, but went defunct in the following turmoils after the end of this dynasty. A short-lived revival of the cult took place in the 12th Dynasty.[37]

Sanctuary of the Knife

The so-called "Sanctuary of the Knife" was built outside the enclosure wall east of the southern temple section and south of the future entry leaves constructed in the second building phase. It was a ritual slaughterhouse for sacrificial animals for the ruler cult. The function and the description of the sanctuary are verified through papyri in the mortuary temple of Neferirkare. The building was constructed from mud brick and its external wall had round corners. The northern part of the sanctuary included an open slaughterhouse as well as in the north-east corner a realm for dissection of animals and conservation of meat. The middle and southern part of the building occupied the warehouse for the storage of meat. The meat was possibly dried in the roof terrace.[40] According to the Abusir papyri, 130 bulls were sacrificed in this sanctuary during a ten-day feast.[10]

The Sanctuary of the Knife lost its function in the third building period and was then used as a storage room until it was destroyed in the first half of the 6th Dynasty.[10][40]

Circular wall

The circular wall of the complex was composed of a massive adobe wall, with corners consolidated with limestone blocks. A part of the court in the north-western corner was sectioned. The purpose of this separation is unknown.[40]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Verner 2001d, p. 301.

- ^ Budge 1920, p. 921.

- ^ Arnold 2003, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Verner 2001d, p. 304.

- ^ a b (in German) T. Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 1996, pp. 261–262

- ^ a b c Verner 2001d, p. 306.

- ^ a b c d e Lehner 2008, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Lehner 2008, p. 147.

- ^ a b Verner 1999, pp. 336–345 Neferefre's (Unfinished) Pyramid

- ^ a b c d e f Lehner 1997, pp. 146–148

- ^ a b c d e Verner 1994, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Edwards 1999, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Verner 2001d, p. 302.

- ^ a b Peck 2001, p. 289.

- ^ Lepsius 1913, p. 137.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 136.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Verner 2001d, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Verner 1994, p. 138.

- ^ a b Verner 2001d, pp. 294 & 302–303.

- ^ Verner 2001d, p. 305.

- ^ Verner 2001d, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 85.

- ^ a b Verner 1999, p. 331

- ^ a b c Verner 2001d, pp. 303–304.

- ^ a b c d Lehner 1999, p. 784.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Verner 1994, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sampsell 2000, Vol 11, No. 3 the Ostracon.

- ^ Lehner 1999, p. 778.

- ^ Sampsell 2000, Vol 11, No.3 the Ostracon.

- ^ a b Lehner 2008, p. 784.

- ^ a b c (in German) Rainer Stadelmann: Die ägyptischen Pyramiden. Vom Ziegelbau zum Weltwunder. pp. 174–175

- ^ Verner 1999, pp. 339–340

- ^ a b Verner 1999, pp. 340–341

- ^ a b c d e Verner 1999, pp. 341–345

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. In: Archiv Orientální. volume 69, Prag 2001, p. 396 (PDF)

- ^ a b c Verner 1999, p. 344

Notes

Sources

- Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 1860644651.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Budge, Ernest Alfred Wallis (1920). An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary: with an index of English words, king list, and geological list with indexes, list of hieroglyphic characters, coptic and semitic alphabets, etc. Vol. 2. London: J. Murray. OCLC 636043200.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edwards, Iorwerth (1999). "Abusir". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lehner, Mark (1999). "pyramids (Old Kingdom), construction of". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 778–786. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lepsius, Karl Richard (1913) [1849]. Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopen. Bad Honnef am Rhein: Proff & Co. KG. OCLC 84318033.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peck, William H. (2001). "Lepsius, Karl Richard". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 289−290. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sampsell, Bonnie (2000). "Pyramid Design and Construction – Part I: The Accretion Theory". The Ostracon. 11 (3).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Verner, Miroslav (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Verner, Miroslav (2001d). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 9780802117038.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

General

- Hawass, Zahi (2003). The Treasures of the Pyramids. Amalgamated Book. pp. 249–251. ISBN 9788880952336.

- Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc. ISBN 9780500285473.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Verner, Miroslav (1999). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove/Atlantic. ISBN 978-0802117038.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Specific

- Landgráfová, Renata : Abusir XIV. Faience Inlays from the Funerary Temple of King Raneferef. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule, Miroslav Verner, Hana Vymazalova: Abusir X. The Pyramid Complex of Raneferef. The Papyrus Archive. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule : Quelques pièces du matériel cultuel du temple funéraire de Rêneferef. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. (MDIAK) volume 47), von Zabern, Mainz 1991, pp. 293–304

- Verner, Miroslav et al.: Abusir IX: The Pyramid Complex of Raneferef, I: The Archaeology. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006, ISBN 8020013571

- Verner, Miroslav : Les sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir [avec 16 planches] (= Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. volume 85). 1985, pp. 267–280 with XLIV-LIX suppl.

- Verner, Miroslav : Supplément aux sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir [avec 4 planches] (=Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. volume 86). 1986, pp. 361-366 (PDF)

- Vlčková, Petra : Abusir XV. Stone Vessels from the Mortuary Complex of Raneferef at Abusir. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006.