Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup bid

| Qatar 2022 | |

|---|---|

2022 FIFA World Cup bidding logo | |

| Tournament details | |

| Host country | Qatar |

| Teams | 32 (from 6 confederations) |

| Tournament statistics | |

| Matches played | 62 |

← 2018 2026 → | |

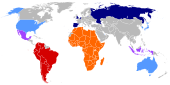

The Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup bid was a bid by Qatar to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup. The bid has come under FBI investigation for bribery and corruption, leading to the resignation of FIFA President Sepp Blatter. With a population of 2 million people, Qatar will be the first Arab state to host the World Cup.[1] Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, son of Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani the then Emir of Qatar, was the chairman of the bid committee.[2] Qatar promoted their hosting of the tournament as representing the Arab World, and has drawn support from across the member states of the Arab League. They also positioned their bid as an opportunity to bridge the gap between the Arab World and the West.[3]

On 17 Nov 2010 Qatar hosted a friendly match between Brazil and Argentina. This was one of 47 international exhibition games held throughout the world on this day.[4]

President of FIFA Sepp Blatter endorsed the idea of having a World Cup in the Arab World, saying in April 2010, "The Arabic world deserves a World Cup. They have 22 countries and have not had any opportunity to organize the tournament." Blatter also praised Qatar's progress, "When I was first in Qatar there were 400,000 people here and now there are 1.6 million. In terms of infrastructure, when you are able to organise the Asian Games (in 2006) with more than 30 events for men and women, then that is not in question."[5] On 2 December 2010, it was announced that Qatar will host the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[6]

Climate

Working against the Qatar bid was the extreme temperature in the desert country. The World Cup always takes place during the European off-season in June and July. During this period the average daytime high in most of Qatar exceeds 50 °C (120 °F), the average daily low temperatures not dropping below 30 °C (86 °F).[7] In response to this issue, Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, the 2022 Qatar bid chairman, has stated, "the event has to be organized in June or July. We will have to take the help of technology to counter the harsh weather. We have already set in motion the process. A stadium with controlled temperature is the answer to the problem. We have other plans up our sleeves as well."[8]

Schedule

| 13–17 September 2010 | Inspection committee visits Qatar[9] |

| 2 December 2010 | FIFA appoint Qatar as host for 2022 World Cup |

Proposed stadiums

The first five proposed stadiums for the World Cup were unveiled at the beginning of March 2010. The stadium will employ cooling technology capable of reducing temperatures within the stadium by up to 20°C (36°F), and the upper tiers of the stadium will be disassembled after the World Cup and donated to countries with less developed sports infrastructure.[10] All of the five stadium projects launched have been designed by German architect Albert Speer & Partners.[11]

The Air Conditioning in the stadiums for both the players and spectators will be solar powered, carbon neutral and provided by Arup of England.[12]

The Al-Khor Stadium is planned for Al-Khor city, located 50 kilometres north of Doha. The stadium will have a total capacity of 45,330, with 19,830 of the seats forming part of a temporary modular upper tier. The Al-Wakrah stadium, to be located in Al-Wakrah city in southern Qatar, will have a total capacity of 45,120 seats. The stadium will also contain a temporary upper tier of 25,500 seats. The stadium will be surrounded by large solar panels and will be decorated with Islamic art. The Al-Wakrah and Al-Khor stadiums would have been built regardless of whether Qatar was awarded the World Cup, according to the bid committee. However, the temporary upper-tier sections would not have been added if Qatar had lost the right to host the tournament.[11]

| Al Daayen | Doha | Doha | Al Khor | Ash-Shamal | Al Wakrah |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lusail Iconic Stadium | Khalifa International Stadium | Sports City Stadium | Al-Khor Stadium | Al-Shamal Stadium | Al-Wakrah Stadium |

| Capacity: 86,250 (planned) |

Capacity: 50,000 (plans to expand to 68,030) |

Capacity: 47,560 (planned) |

Capacity: 45,330 (planned) |

Capacity: 45,120 (planned) |

Capacity: 45,120 (planned) |

|

|

|

|||

| Umm Salal | Doha | Al Rayyan | Al Rayyan | Al Rayyan | Doha |

| Umm Salal Stadium | Doha Port Stadium | Education City Stadium | Al-Gharafa Stadium | Al Rayyan Stadium | Qatar University Stadium |

| Capacity: 45,120 (planned) |

Capacity: 44,950 (planned) |

Capacity: 45,350 (planned) |

Capacity: 21,282 (plans to expand to 44,740) |

Capacity: 21,282 (plans to expand to 44,740) |

Capacity: 43,520 (planned) |

|

Controversy

Allegations of slave labor

A September 2013 report by The Guardian said a number of Nepalese migrant workers have faced poor conditions as companies handling construction for 2022 World Cup infrastructure forced workers to stay by denying them promised salaries and withholding necessary worker ID permits, rendering them illegal aliens. The Guardian wrote that their investigation "found evidence to suggest that thousands of Nepalese, who make up the single largest group of laborers in Qatar, face exploitation and abuses that amount to modern-day slavery, as defined by the International Labour Organisation, during a building binge paving the way for 2022." Nepalese workers in Qatar have been dying at a rate of one per day.[13]

A video report accompanying The Guardian's article showed men living in labor camps with unsanitary and dilapidated conditions. Workers told The Guardian they were promised high salaries before coming to Qatar and then their contracts were destroyed upon their arrival to Qatar. Some said they hadn't been paid in months, but the construction companies denied them their worker IDs or passports, rendering them trapped. Workers described having to beg for food and being beaten. They could try to escape, but if caught without proper papers, they would be arrested.[14]

The Qatar 2022 Supreme Committee denied that construction directly related to the World Cup had yet begun but told The Guardian they are "deeply concerned with the allegations" and said, "We have been informed that the relevant government authorities are conducting an investigation into the allegations."

In 2013, 185 Nepalese died working as migrant construction workers building infrastructure in Qatar.[15] A report released by the International Trade Union Confederation in March 2014 estimated that 4,000 more workers could die as Qatar prepares for the World Cup.[16]

Human rights group Amnesty International has asked FIFA to intervene to protect migrant workers from mistreatment.[17]

In March 2016, Amnesty International accused Qatar of using forced labour and forcing the employees to live in poor conditions and withholding their wages and passports. It accused Fifa of failing to stop the stadium being built on "human right abuses". Migrant workers told Amnesty about verbal abuse and threats they received after complaining about not being paid for up to several months. Nepali workers were even denied leave to visit their family after the 2015 Nepal earthquake. [18]

Allegations of bribery

During May 2011, allegations of bribery on the part of two members of the FIFA Executive Committee were tabled by Lord Triesman of the English FA. These allegations were based on information from a whistleblower involved with the Qatari bid. FIFA has since opened an internal inquiry into the matter, and a revote on the 2022 World Cup remains a possibility if the allegations are proven. FIFA president Sepp Blatter has admitted that there is a ground swell of popular support to re-hold the 2022 vote won by Qatar.[19]

In testimony to a UK parliamentary inquiry board in May 2011, Lord Triesman alleged that Trinidad and Tobago's Jack Warner demanded $4 million for an education center in his country and Paraguay's Nicolás Léoz asked for an honorary knighthood in exchange for their votes. Also, two Sunday Times reporters testified that they had been told that Jacques Anouma of the Ivory Coast and Issa Hayatou of Cameroon were each paid $1.5 million to support Qatar's bid for the tournament. All four have denied the allegations.[20] Mohammed bin Hammam, who played a key role in securing the games for Qatar, withdrew as a candidate for president of FIFA in May 2011 after being accused of bribing 25 FIFA officials to vote for his candidacy.[21] Both Bin Hammam and Warner were suspended by FIFA in wake of these allegations,[22] with Warner reacting to his suspension by questioning Blatter's conduct and adding that FIFA secretary general Jerome Valcke had also told him that Qatar had bought the 2022 World Cup.[23] Valcke subsequently issued a statement denying he had suggested it was bribery, saying instead that the country had "used its financial muscle to lobby for support".

Qatar officials denied any impropriety and insist that the corruption allegations are being driven by envy and mistrust by those who do not want the World Cup staged in such a country. Qatar Airways CEO Akbar Al Baker gave an interview to German media in June 2014 stating that the country is not getting the respect it deserves over its efforts to hold the World Cup and that the Qatari Emir strictly punishes and forbids instances of corruption and bribery with a zero-tolerance policy.".[24][25]

Weather

The World Cup is usually held in the northern hemisphere summer. During this season in Qatar, the temperature can get to 50 °C (122 °F).[26] Qatar says that this will not be a problem for it hosting the World Cup. A section from Qatar 2022 Bid official site explains:

- "Each of the five stadia will harness the power of the sun's rays to provide a cool environment for players and fans by converting solar energy into electricity that will then be used to cool both fans and players at the stadia. When games are not taking place, the solar installations at the stadia will export energy onto the power grid. During matches, the stadia will draw energy from the grid. This is the basis for the stadia's carbon-neutrality. Along with the stadia, we plan to make the cooling technologies we’ve developed available to other countries in hot climates, so that they too can host major sporting events."

Qatar declared their intention to change the dates of the World Cup to winter immediately upon being award the Cup because of all the controversy surrounding the topic. An example of this is during the 2018 World Cup qualifier with China under air conditioning, which happened in the 8th of October 2015.

Such cooling techniques will be able to reduce temperatures from 45 to 25 degrees Celsius (113 to 77 °F), which would be comfortable for players and spectators during matches, the bid also proposes these cooling technologies to be used in fan-zones, training pitches and walkways between Metro stations and stadia.[27]

Alcohol

Alcohol can currently be consumed legally in hotel bars and clubs by showing a passport for reporting and a special permit to attend the club. The question of whether alcohol was allowed to be consumed in additional areas and at the games themselves was asked, Hassan Abdullah al Thawed, chief executive of the Qatar 2022 World Cup bid, said the Muslim state would also permit alcohol consumption during the World Cup. A few specific fan-zones will be set up during the event, that will provide alcohol for sale. Also certain bars are now being developed for all the tourists coming to support their chosen teams in the world cup.[28][29]

LGBT fans

The selection of Qatar as hosts attracted controversy, as homosexuality is illegal in Qatar. FIFA President Sepp Blatter came under fire for joking, "I would say they should refrain from any sexual activities." He added, however: "We are definitely living in a world of freedom and I'm sure when the World Cup will be in Qatar in 2022, there will be no problems." [30] He later said, "We (FIFA) don't want any discrimination. What we want to do is open this game to everybody, and to open it to all cultures, and this is what we are doing in 2022."[31][32][33][34][35][36][37]

Israel

During and after the bidding process, the Qatari government stated that it would let the Israel national football team participate in the World Cup on their territory despite not recognizing the State of Israel,[28][29][38] the head of Qatar’s World Cup bid said. Israeli athletes had competed previously in Qatar, such as Israeli tennis player Shahar Pe'er in 2008.[39] In addition, an Israeli also participated in the Doha 2010 Indoor Championships.[40]

During the 2014 Protective Edge operation in the Gaza Strip between Israel and Hamas, Israel's economy minister Naftali Bennett alleged that Qatar supported Hamas and was "a terror sponsor", and called upon FIFA to give the 2022 World Cup to another country.[41][42]

Official bid partners

- QNB Group

- Qatar Airways

- Blue Salon

- Lambie-Nairn

See also

References

- ^ Vesty, Marc (17 March 2009). "The 'race' to host World Cup 2018 and 2022". BBC Sport. London.

- ^ "Qatar 2022 announces Bid Committee leadership". Dubai Chronicle. 25 March 2009.

- ^ "Qatar launch "unity" bid to stage 2022 World Cup finals". ESPN. 17 May 2009.

- ^ "Argentina win Qatar's Latin clash Announced". 17 November 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Blatter reaches out to Arabia". Al Jazeera. 2010-04-25. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ "2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup Hosts Announced". BBC News. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Doha, Qatar". weather.com. The Weather Channel. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Tripathi, Raajiv; Nag, Arindam (25 March 2009). "Qatar will be great host for WC 2022". Qatar Tribune. Doha.

- ^ "FIFA receives bidding documents for 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups" (Press release). FIFA.com. 2010-05-14. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- ^ "Bidding Nation Qatar 2022 – Stadiums". www.recruitmentvartha.com. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ^ a b "2022 FIFA World Cup Bid Evaluation Report: Qatar" (PDF). FIFA. 2010-12-05.

- ^ "BBC World Service - News - Qatar 2022: How to build comfortable stadiums in a hot climate". bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Revealed: Qatar's World Cup 'slaves'". The Guardian (UK).

- ^ "Qatar: the migrant workers forced to work for no pay in World Cup host country – video". The Guardian (UK).

- ^ Owen Gibson. "Qatar World Cup: 185 Nepalese died in 2013 – official records". the Guardian.

- ^ "Migrant Workers In World Cup Host Qatar 'Enslaved,' Living In Squalor: Report". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "Amnesty calls on FIFA to address Qatar workers' rights". Reuters.

- ^ "Qatar 2022: 'Forced labour' at World Cup stadium". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

- ^ [1], Qatar may be stripped off FIFA World Cup 2022: Sepp Blatter.

- ^ Sports Illustrated, "Sorry Soccer", 23 May 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Associated Press, "Bin Hammam leaves race after allegations", Japan Times, 30 May 2011, p. 16.

- ^ "Fifa suspends Bin Hammam and Jack Warner". BBC News. 2011-05-29.

- ^ "AOL Sport - Powered by Sporting Life". fanhouse.co.uk.

- ^ "Terms of trade union are killing Lufthansa". Handelsblatt. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ "Qataris brush off allegations of buying World Cup rights". Reuters. 2011-05-30.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica Qatar Climate". britannica.com. 2011-01-17. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ^ "Qatar 2022 World Cup Bid Reveals New Stadium Plans and Cooling Technologies". Worldfootballinsider.com. 2010-04-28. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ a b Tamara Walid. "Qatar would 'welcome' Israel in 2022". Thenational.ae. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ a b "World Cup – Qatar 2022 green lights Israel, booze". Yahoo! Eurosport UK. 2009-11-10. Archived from the original on 2009-11-15. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ "Sepp Blatter in hot water for making 'gay joke' when discussing Qatar World Cup 2022". The Telegraph.

- ^ Gibson, Owen (2010-12-14). "World news,World Cup 2022 (Football),Sepp Blatter,Fifa,Football,Sport". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "FIFA President: Gay Fans 'Should Refrain From Any Sexual Activities' During 2022 World Cup In Qatar". fitperez.com.

- ^ "Blatter sparks Qatar gay furore". BBC News. 2010-12-14.

- ^ "Gay rights group wants apology from FIFA's Sepp Blatter for comments - ESPN". ESPN.com.

- ^ http://www.thesportreview.com/tsr/2010/12/sepp-blatter-gays-qatar-world-cup-2022/.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "FIFA president says gays should refrain from homosexuality during Qatar World Cup". PinkNews.

- ^ "FIFA President: Gay Fans 'Should Refrain From Any Sexual Activities' During 2022 World Cup In Qatar". Huffington Post. 2010-12-13.

- ^ "Qatar to allow Israel, alcohol at World Cup". Kuwait Times. 2009-11-11. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ Robson, Douglas (2008-02-19). "Peer wins history-making match at Qatar tourney". USA Today.

- ^ "Gezachw Yossef Biography". iaaf.org. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ "Bennett Calls to Cancel World Cup in 'Terror Sponsor' Qatar". israelnationalnews.com. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ "Bennett to Al Jazeera: Your owner Qatar funds the daily murder of children in Israel and Gaza". Al Gazeera. Retrieved 2014-08-20.