Titanic: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by Patriot4444 to last revision by December21st2012Freak (HG) |

Patriot4444 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 431: | Line 431: | ||

-->lastsong.asp T-lastsong]. |

-->lastsong.asp T-lastsong]. |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

But [[Walter Lord]]'s book ''[[A Night to Remember (book)|A Night to Remember]]'' |

But [[Walter Lord]]'s book ''[[A Night to Remember (book)|A Night to Remember]]'' popularized wireless operator [[Harold Bride]]'s 1912 account (''New York Times'') that he heard the song "Autumn" before the ship sank. It is considered Bride either meant the hymn called "Autumn" or waltz "Songe d'Automne" but neither were in the White Star Line songbook for the band.<ref name=Ssong/> Bride is the only witness who was close enough to the band, as he floated off the deck before the ship went down, to be considered reliable—Mrs. Dick had left by lifeboat an hour and 20 minutes earlier and could not possibly have heard the band's final moments. The notion that the band played "Nearer, My God, to Thee" as a swan song is possibly a myth originating from the wrecking of the [[SS Valencia|SS ''Valencia'']], which had received wide press coverage in Canada in 1906 and so may have influenced Mrs. Dick's recollection.<ref name = "The Myth of the Titanic"/> Also, there are two, very different, musical settings for "Nearer, My God, to Thee": one is popular in Britain, and the other is popular in the U.S., and the British melody might sound like the other hymn ("Autumn"). The film ''[[A Night to Remember (1958 film)|A Night to Remember]]'' (1958) uses the British setting; while the 1953 film ''[[Titanic (1953 film)|Titanic]]'', with Clifton Webb, uses the American setting; but Cameron's ''[[Titanic (1997 film)|Titanic]]'' (1997) has passengers singing the hymn "Autumn" as only Harold Bride indicated.<ref name=Ssong/> |

||

===The Predictions of W.T. Stead=== |

===The Predictions of W.T. Stead=== |

||

Revision as of 19:14, 24 August 2009

| File:Titanic southhampton.jpg RMS Titanic before departing Southampton, England. Photo taken Good Friday 5 April 1912

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | RMS Titanic |

| Owner | |

| Port of registry | |

| Route | Southampton to New York City |

| Ordered | July 31, 1908[2] |

| Builder | Harland and Wolff yards in Belfast, Ireland |

| Yard number | 401 |

| Laid down | 31 March 1909 |

| Launched | 31 May 1911 |

| Christened | Not christened |

| Completed | 31 March 1912 |

| Maiden voyage | 10 April 1912 |

| Identification | list error: <br /> list (help) Radio Callsign "MGY" UK Official Number: 131428 |

| Fate | Sank on 15 April 1912 after hitting an iceberg |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 46,328 GRT GRT uses unsupported parameter (help) |

| Displacement | 52,310 tons |

| Length | 882 ft 9 in (269.1 m)*[3] |

| Beam | 92 ft 0 in (28.0 m)*[3] |

| Height | 175 ft (53.3 m)* (Keel to top of funnels) |

| Draught | 34 ft 7 in (10.5 m)* |

| Depth | 64 ft 6 in (19.7 m)*[3] |

| Decks | 9 (Lettered A through G with boilers below) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | |

| Capacity | list error: mixed text and list (help) Passengers and crew (fully loaded):

Staterooms (840 total):

|

| Topics about Titanic | |

|---|---|

The RMS Titanic was an Olympic-class passenger liner owned by British shipping company White Star Line and built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, United Kingdom. For her time, she was the largest passenger steamship in the world.

On the night of 14 April 1912, during the ship's maiden voyage, Titanic hit an iceberg and sank two hours and forty minutes later, early on 15 April 1912. The sinking resulted in the deaths of 1,517 people, making it one of the deadliest peacetime maritime disasters in history. The high casualty rate was due in part to the fact that, although complying with the regulations of the time, the ship did not carry enough lifeboats for everyone aboard. The ship had a total lifeboat capacity of 1,178 people, although her capacity was 3,547. A disproportionate number of men died due to the women-and-children-first protocol that was followed.

The Titanic used some of the most advanced technology available at the time and was popularly believed to have been described as "unsinkable."[6] It was a great shock to many that, despite the extensive safety features and experienced crew, the Titanic sank. The frenzy on the part of the media about Titanic's famous victims, the legends about the sinking, the resulting changes to maritime law, and the discovery of the wreck have contributed to the continuing interest in, and notoriety of, the Titanic.

Construction

The Titanic was a White Star Line ocean liner, built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, and designed to compete with the rival Cunard Line's Lusitania and Mauretania. The Titanic, along with her Olympic-class sisters, the Olympic and the soon-to-be-built Britannic (which was to be called Gigantic at first), were intended to be the largest, most luxurious ships ever to operate. The designers were Lord William Pirrie,[7] a director of both Harland and Wolff and White Star, naval architect Thomas Andrews, Harland and Wolff's construction manager and head of their design department,[8] and Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard's chief draughtsman and general manager.[9] Carlisle's role in this project was the design of the superstructure of these ships, particularly the superstructures' streamlined joining to the hulls[citation needed] as well as the implementation of an efficient lifeboat davit design. Carlisle would leave the project in 1910, before the ships were launched, when he became a shareholder in Welin Davit & Engineering Company Ltd, the firm making the davits.[10]

Construction of RMS Titanic, funded by the American J.P. Morgan and his International Mercantile Marine Co., began on 31 March, 1909. Titanic's hull was launched on 31 May 1911, and her outfitting was completed by 31 March the following year. She was 882 feet 9 inches (269.1 m)* long and 92 feet 0 inches (28.0 m)* wide,[3] with a gross register tonnage of 46,328 long tons and a height from the water line to the boat deck of 59 feet (18 m). She was equipped with two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion, inverted steam engines and one low-pressure Parsons turbine, which powered three propellers. There were 29 boilers fired by 159 coal burning furnaces that made possible a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph). Only three of the four 62 feet (19 m) funnels were functional: the fourth, which served only for ventilation purposes, was added to make the ship look more impressive. The ship could carry a total of 3,547 passengers and crew.

Features

In her time, Titanic surpassed all rivals in luxury and opulence. She offered an on-board swimming pool, a gymnasium, a squash court, a Turkish bath, a Verandah Cafe and libraries in both the first and second class. [11] First-class common rooms were adorned with ornate wood panelling, expensive furniture and other decorations. The third class general room had pine paneling and sturdy teak furniture.[12] There were also barber shops in both the first and second class. In addition, the Café Parisien offered cuisine for the first-class passengers, with a sunlit veranda fitted with trellis decorations.[13]

The ship incorporated technologically advanced features for the period. She had 3 electric elevators in first class and 1 in second class. She had also an extensive electrical subsystem with steam-powered generators and ship-wide wiring feeding electric lights, two Marconi radios, including a powerful 1,500-watt set manned by two operators working in shifts, allowing constant contact and the transmission of many passenger messages.[14] First-class passengers paid a hefty fee for such amenities. The most expensive one-way trans-Atlantic passage was $4,350 (which is more than $80,000 in today's currency).[15]

Lifeboats

For its maiden voyage, Titanic carried a total of 20 lifeboats of three different varieties:[16]

- Lifeboats 1 and 2 - emergency wooden cutters: 25'2" long by 7'2" wide by 3'2" deep; capacity 326.6 cubic feet or 40 persons

- Lifeboats 3 to 16 - wooden lifeboats: 30' long by 9'1" wide by 4' deep; capacity 655.2 cubic feet or 65 persons

- Lifeboats A, B, C and D - Englehardt 'collapsible' lifeboats: 27'5" long by 8' wide by 3' deep; capacity 376.6 cubic feet or 47 persons

Total capacity of 1,178 persons.

The lifeboats were predominantly stowed in chocks on the boat deck, not connected to the falls of the davits. Those on the starboard side were numbered 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 15 from the bow, while those on the port side were numbered 2,4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16 from the bow. The emergency cutters (lifeboats 1 and 2) were kept swung out, hanging from the davits, ready for immediate use while collapsible lifeboats C and D were stowed on the boat deck immediately in-board of boats 1 and 2 respectively. Collapsible lifeboats A and B were, however, kept on the roof of the officer's quarters, on either side of number 1 funnel. During the sinking, this proved to make these boats difficult to launch as it was first necessary to slide the boats on timbers down to the boat deck. During this procedure, collapsible B capsized and subsequently floated off the ship upside down.

At the design stage Carlisle suggested that Titanic use a new, larger type of davit, manufactured by the Welin Davit & Engineering Co Ltd, each of which could handle 4 lifeboats. 16 sets of these davits were installed, giving Titanic the ability to carry 64[17] wooden lifeboats — a total capacity of over 4000 people, compared with Titanic's total carrying capacity of about 3,600 passengers and crew. However, the White Star Line, while agreeing to the new davits, decided that only 16 wooden lifeboats (16 being the minimum allowed by the Board of Trade, based on the Titanic's projected tonnage) would be carried (there were also four folding lifeboats, called collapsibles), which could accommodate only 1,178 people (33% of Titanic's total capacity). At the time, the Board of Trade's regulations stated that British vessels over 10,000 tons must carry 16 lifeboats with a capacity of 5,500 cubic feet (160 m3), plus enough capacity in rafts and floats for 75% (or 50% in case of a vessel with watertight bulkheads) of that in the lifeboats. Therefore, the White Star Line actually provided more lifeboat accommodation than was legally required.[18]

The regulations had made no extra provision for larger ships since 1894, when the largest passenger ship under consideration was the Cunard Line's Lucania, only 13,000 tons. Sir Alfred Chalmers, nautical adviser to the Board of Trade from 1896 to 1911, had considered the matter "from time to time", but because he thought that experienced sailors would have to be carried "uselessly" aboard ship for no other purpose than lowering and manning lifeboats, and the difficulty he anticipated in getting away a greater number than 16 in any emergency, he "did not consider it necessary to increase [our scale]".[19]

Carlisle told the official inquiry that he had discussed the matter with J. Bruce Ismay, White Star's Managing Director, but in his evidence Ismay denied that he had ever heard of this, nor did he recollect noticing such provision in the plans of the ship he had inspected.[10][20] Ten days before the maiden voyage Axel Welin, the maker of Titanic's lifeboat davits, had announced that his machinery had been installed because the vessel's owners were aware of forthcoming changes in official regulations, but Harold Sanderson, vice-president of the International Mercantile Marine and former general manager of the White Star Line, denied that this had been the intention.[21]

Comparisons with the Olympic

The Titanic closely resembled her older sister Olympic. Although she enclosed more space and therefore had a larger gross register tonnage, the hull was almost the same length as the Olympic's. However, there were a few differences. Two of the most noticeable were that half of the Titanics's forward promenade A-Deck (below the boat deck) was enclosed against outside weather, and her B-Deck configuration was different from the Olympic's. As built the Olympic did not have an equivalent of the Titanic's Café Parisien: the feature was not added until 1913. Some of the flaws found on the Olympic, such as the creaking of the aft expansion joint, were corrected on the Titanic. The skid lights that provided natural illumination on A-deck were round, while on Olympic they were oval. The Titanic's wheelhouse was made narrower and longer than the Olympic's.[22] These, and other modifications, made the Titanic 1,004 gross register tons larger than the Olympic and thus the largest active ship in the world during her maiden voyage in April 1912.

Ship history

Sea trials

Titanic's sea trials took place shortly after after she was fitted out at Harland & Wolff shipyard. The trials were originally scheduled for 10.00am on Monday, 1 April, just 9 days before she was due to leave Southampton on her maiden voyage, but poor weather conditions forced the trials to be postponed until the following day. Aboard Titanic were 78 stokers, greasers and firemen, and 41 members of crew. No domestic staff appear to have been aboard. Representatives of various companies travelled on Titanic's sea trials, including Harold A. Sanderson of I.M.M and Thomas Andrews and Edward Wilding of Harland and Wolff. Bruce Ismay and Lord Pirrie were too ill to attend. Jack Phillips and Harold Bride served as radio operators, and performed fine-tuning of the Marconi equipment. Mr Carruthers, a surveyor from the Board of Trade, was also present to see that everything worked, and that the ship was fit to carry passengers. After the trial, he signed an 'Agreement and Account of Voyages and Crew', valid for twelve months, which deemed the ship sea-worthy.[23]

Maiden voyage

The vessel began her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, bound for New York City, New York, on Wednesday, 10 April 1912, with Captain Edward J. Smith in command. As the Titanic left her berth, her wake caused the liner City of New York, which was docked nearby, to break away from her moorings, whereupon she was drawn dangerously close (about four feet) to the Titanic before a tugboat towed the New York away.[24] The incident delayed departure for one hour [citation needed]. After crossing the English Channel, the Titanic stopped at Cherbourg, France, to board additional passengers and stopped again the next day at Queenstown (known today as Cobh), Ireland. As harbour facilities at Queenstown were inadequate for a ship of her size, Titanic had to anchor off-shore, with small boats, known as tenders, ferrying the embarking passengers out to her. When she finally set out for New York, there were 2,240 people aboard.[25]

John Coffey, a 23-year-old crewmember, jumped ship by stowing away on a tender and hid amongst mailbags headed for Queenstown. Coffey stated that the reason for smuggling himself off the liner was that he held a superstition about sailing and specifically about travelling on the Titanic. However, he later signed on to join the crew of the Mauretania.[26]

On the maiden voyage of the Titanic some of the most prominent people of the day were travelling in first–class. Some of these included millionaire John Jacob Astor IV and his wife Madeleine Force Astor, industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim, Macy's owner Isidor Straus and his wife Ida, Denver millionairess Margaret "Molly" Brown, Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife couturière Lucy (Lady Duff-Gordon), George Elkins Widener and his wife Eleanor; cricketer and businessman John Borland Thayer with his wife Marian and their seventeen-year-old son Jack, journalist William Thomas Stead, the Countess of Rothes, United States presidential aide Archibald Butt, author and socialite Helen Churchill Candee, author Jacques Futrelle his wife May and their friends, Broadway producers Henry and Rene Harris and silent film actress Dorothy Gibson among others.[27] J.P. Morgan was scheduled to travel on the maiden voyage, but canceled at the last minute.[28]. Traveling in first–class aboard the ship were White Star Line's managing director J. Bruce Ismay and the ship's builder Thomas Andrews, who was on board to observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new ship.[27]

Sinking

On the night of Sunday, 14 April 1912, the temperature had dropped to near freezing and the ocean was calm. The moon was not visible and the sky was clear. Captain Smith, in response to iceberg warnings received via wireless over the preceding few days, altered the Titanic's course slightly to the south. That Sunday at 13:45,[a] a message from the steamer Amerika warned that large icebergs lay in the Titanic's path, but as Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, the Marconi wireless radio operators, were employed by Marconi [29] and paid to relay messages to and from the passengers,[30] they were not focused on relaying such "non-essential" ice messages to the bridge.[31] Later that evening, another report of numerous large icebergs, this time from the Mesaba, also failed to reach the bridge.

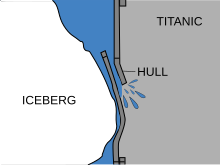

At 23:40, while sailing about 400 miles south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, lookouts Fredrick Fleet and Reginald Lee spotted a large iceberg directly ahead of the ship. Fleet sounded the ship's bell three times and telephoned the bridge exclaiming, "Iceberg, right ahead!". First Officer Murdoch gave the order "hard-a-starboard", using the traditional tiller order for an abrupt turn to port (left), and adjusted the engines (he either ordered through the telegraph for "full reverse" or "stop" on the engines, survivor testimony on this conflicts[32][33][34]). The iceberg brushed the ship's starboard side (right side), buckling the hull in several places and popping out rivets below the waterline over a length of 299 feet (90 m). As seawater filled the forward compartments, the watertight doors shut. However, while the ship could stay afloat with four flooded compartments, five were filling with water. The five water-filled compartments weighed down the ship so that the tops of the forward watertight bulkheads fell below the ship's waterline, allowing water to pour into additional compartments. Captain Smith, alerted by the jolt of the impact, arrived on the bridge and ordered a full stop. Shortly after midnight on 15 April, following an inspection by the ship's officers and Thomas Andrews, the lifeboats were ordered to be readied and a distress call was sent out.

Wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride were busy sending out CQD, the international distress signal. Several ships responded, including Mount Temple, Frankfurt and Titanic's sister ship, Olympic, but none was close enough to make it in time.[35] The closest ship to respond was Cunard Line's Carpathia 58 miles (93 km) away, which could arrive in an estimated four hours—too late to rescue all of Titanic's passengers. The only land–based location that received the distress call from Titanic was a wireless station at Cape Race, Newfoundland.[35]

From the bridge, the lights of a nearby ship could be seen off the port side. The identity of this ship remains a mystery but there have been theories suggesting that it was probably either the Californian or a sealer called the Sampson.[36] As it was not responding to wireless, Fourth Officer Boxhall and Quartermaster Rowe attempted signalling the ship with a Morse lamp and later with distress rockets, but the ship never appeared to respond.[37] The Californian, which was nearby and stopped for the night because of ice, also saw lights in the distance. The Californian's wireless was turned off, and the wireless operator had gone to bed for the night. Just before he went to bed at around 23:00 the Californian's radio operator attempted to warn the Titanic that there was ice ahead, but he was cut off by an exhausted Jack Phillips, who had fired back an angry response, "Shut up, shut up, I am busy; I am working Cape Race", referring to the Newfoundland wireless station. [38] When the Californian's officers first saw the ship, they tried signalling her with their Morse lamp, but also never appeared to receive a response. Later, they noticed the Titanic's distress signals over the lights and informed Captain Stanley Lord. Even though there was much discussion about the mysterious ship, which to the officers on duty appeared to be moving away, the Californian did not wake her wireless operator until morning.[37]

Lifeboats launched

The first lifeboat launched was Lifeboat 7 on the starboard side with 28 people on board out of a capacity of 65. It was lowered at around 00:40 as believed by the British Inquiry.[39][40] Lifeboat 6 and Lifeboat 5 were launched ten minutes later. Lifeboat 1 was the fifth lifeboat to be launched with 12 people. Lifeboat 11 was overloaded with 70 people. Collapsible D was the last lifeboat to be launched. The Titanic carried 20 lifeboats with a total capacity of 1,178 people. While not enough to hold all of the passengers and crew, the Titanic carried more boats than was required by the British Board of Trade Regulations. At the time, the number of lifeboats required was determined by a ship's gross register tonnage, rather than her human capacity.

The Titanic showed no outward signs of being in imminent danger, and passengers were reluctant to leave the apparent safety of the ship to board small lifeboats. As a result, most of the boats were launched partially empty; one boat meant to hold 40 people left the Titanic with only 12 people on board it. With "Women and children first" the imperative for loading lifeboats, Second Officer Lightoller, who was loading boats on the port side, allowed men to board only if oarsmen were needed, even if there was room. First Officer Murdoch, who was loading boats on the starboard side, let men on board if women were absent. As the ship's list increased people started to become nervous, and some lifeboats began leaving fully loaded. By 02:05, the entire bow was under water, and all the lifeboats, save for two, had been launched.

Final minutes

Around 02:10, the stern rose out of the water exposing the propellers, and by 02:17 the waterline had reached the boat deck. The last two lifeboats floated off the deck, one upside down, the other half-filled with water. Shortly afterwards, the forward funnel collapsed, crushing part of the bridge and people in the water. On deck, people were scrambling towards the stern or jumping overboard in hopes of reaching a lifeboat. The ship's stern slowly rose into the air, and everything unsecured crashed towards the water. While the stern rose, the electrical system finally failed and the lights went out. Shortly afterwards, the stress on the hull caused Titanic to break apart between the last two funnels, and the bow went completely under. The stern righted itself slightly and then rose vertically. After a few moments, at 02:20, this too sank into the ocean.

Only two of the 18 launched lifeboats rescued people after the ship sank. Lifeboat 4 was close by and picked up five people, two of whom later died. Close to an hour later, lifeboat 14 went back and rescued four people, one of whom died afterwards. Other people managed to climb onto the lifeboats that floated off the deck. There were some arguments in some of the other lifeboats about going back, but many survivors were afraid of being swamped by people trying to climb into the lifeboat or being pulled down by the suction from the sinking Titanic, though it turned out that there had been very little suction.

As the ship fell into the depths, the two sections behaved very differently. The streamlined bow planed off approximately 2,000 feet (609 m) below the surface and slowed somewhat, landing relatively gently. The stern plunged violently to the ocean floor, the hull being torn apart along the way from massive implosions caused by compression of the air still trapped inside. The stern smashed into the bottom at considerable speed, grinding the hull deep into the silt.

After steaming under a forced draft for just under four hours, the RMS Carpathia arrived in the area and at 04:10 began rescuing survivors. By 08:30 she picked up the last lifeboat with survivors and left the area at 08:50 bound for New York.[41]

Aftermath

Arrival of Carpathia in New York

On 18 April, the Carpathia docked at Pier 54 at Little West 12th Street in New York with the survivors. It arrived at night and was greeted by thousands of people. The Titanic had been headed for 20th Street. The Carpathia dropped off the empty Titanic lifeboats at Pier 59, as property of the White Star Line, before unloading the survivors at Pier 54. Both piers were part of the Chelsea Piers built to handle luxury liners of the day. As news of the disaster spread, many people were shocked that the Titanic could sink with such great loss of life despite all of her technological advances. Newspapers were filled with stories and descriptions of the disaster and were eager to get the latest information. Many charities were set up to help the victims and their families, many of whom lost their sole breadwinner, or, in the case of third class survivors, lost everything they owned.[42] The people of Southampton were deeply affected by the sinking. According to the Hampshire Chronicle on 20 April 1912, almost 1,000 local families were directly affected. Almost every street in the Chapel district of the town lost more than one resident and over 500 households lost a member.[43]

Survivors, victims and statistics

| Category | Number aboard | Number of survivors | Percentage survived | Number lost | Percentage lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First class | 329 | 199 | 60.5 % | 130 | 39.5 % |

| Second class | 285 | 119 | 41.7 % | 166 | 58.3 % |

| Third class | 710 | 174 | 24.5 % | 536 | 75.5 % |

| Crew | 899 | 214 | 23.8 % | 685 | 76.2 % |

| Total | 2,223 | 706 | 31.8 % | 1,517 | 68.2 % |

Of a total of 2,223 people aboard the Titanic only 706 survived the disaster and 1,517 perished.[44] The majority of deaths were caused by hypothermia in the 28 °F (−2 °C) water.[45] Men and members of the lower classes were less likely to survive. Of male passengers in second class, 92 percent perished. Third class passengers fared very badly.

6 of the 7 children in first class and all of the children in second class survived, whereas only 34 percent were saved in third class. 4 first class women died and 86 percent women survived in second class and less than half survived in third class. Overall, only 20 percent of the men survived, compared to nearly 75 percent of the women. First-class men were four times as likely to survive as second-class men, and twice as likely to survive as third class men.[46]

Another disparity is that a greater percentage of British passengers died than American passengers; some sources claim this could be because many Britons of the time were too polite and queued, rather than to force and elbow their way onto the lifeboats as some Americans did. The captain, Edward John Smith, shouted out: "Be British, boys, be British!" as the cruise liner went down, according to witnesses. [47][48]

- In one case in the third class, a Swedish family lost the mother, Alma Pålsson, and her four children, all aged under 10. The father was waiting for them to arrive at the destination. "Paulson's grief was the most acute of any who visited the offices of the White Star, but his loss was the greatest. His whole family had been wiped out."[49]

- The sailors aboard the ship CS Mackay-Bennett which recovered bodies from Titanic, who were very upset by the discovery of the unknown boy's body, paid for a monument and he was buried on 4 May 1912 with a copper pendant placed in his coffin by the sailors that read "Our Babe". The unknown child was later positively identified as Sidney Leslie Goodwin.

- One survivor, stewardess Violet Jessop, who had been on board the RMS Olympic when she collided with HMS Hawke in 1911, went on to survive the sinking of HMHS Britannic in 1916.

- There are no living survivors of the Titanic disaster. The last living survivor was Millvina Dean, who was only nine weeks old at the time of the sinking. She died on 31 May 2009, the 98th anniversary of the launching of the ship's hull. She lived in Southampton, England.[50]

- There are many stories relating to dogs on the Titanic. Apparently, a passenger released the dogs just before the ship went down; they were seen running up and down the decks. At least two dogs survived.[51]

Retrieval and burial of the dead

Once the massive loss of life became clear, White Star Line chartered the cable ship CS Mackay-Bennett from Halifax, Nova Scotia to retrieve bodies. Three other ships followed in the search, the cable ship Minia, the lighthouse supply ship Montmagny and the sealing vessel Algerine. Each ship left with embalming supplies, undertakers, and clergy. Of the 333 victims that were eventually recovered, 328 were retrieved by the Canadian ships and five more by passing North Atlantic steamships. For some unknown reason, numbers 324 and 325 were unused, and the six passengers buried at sea by the Carpathia also went unnumbered.[52] In mid-May 1912, over 200 miles (320 km) from the site of the sinking, the Oceanic recovered three bodies, numbers 331, 332 and 333, who were occupants of Collapsible A, which was swamped in the last moments of the sinking. Several people managed to reach this lifeboat, although some died during the night. When Fifth Officer Harold Lowe rescued the survivors of Collapsible A, he left the three dead bodies in the boat: Thomas Beattie, a first-class passenger, and two crew members, a fireman and a seaman. The bodies were buried at sea from Oceanic.[53]

The first body recovery ship to reach the site of the sinking, the cable ship CS Mackay-Bennett found so many bodies that the embalming supplies aboard were quickly exhausted. Health regulations only permitted that embalmed bodies could be returned to port.[54] Captain Larnder of the Mackay-Bennett and undertakers aboard decided to preserve all bodies of First Class passengers, justifying their decision by the need to visually identify wealthy men to resolve any disputes over large estates. As a result the burials at sea were third class passengers and crew. Larnder himself claimed that as a mariner, he would expect to be buried at sea.[55] However complaints about the burials at sea were made by families and undertakers. Later ships such as Minia found fewer bodies, requiring fewer embalming supplies, and were able to limit burials at sea to bodies which were too damaged to preserve.

Bodies recovered were preserved to be taken to Halifax, the closest city to the sinking with direct rail and steamship connections. The Halifax coroner, John Henry Barnstead, developed a detailed system to identify bodies and safeguard personal possessions. His identification system would later be used to identify victims of the Halifax Explosion in 1917. Relatives from across North America came to identify and claim bodies. A large temporary morgue was set up in a curling rink and undertakers were called in from all across Eastern Canada to assist.[53] Some bodies were shipped to be buried in their hometowns across North America and Europe. About two-thirds of the bodies were identified. Unidentified victims were buried with simple numbers based on the order in which their bodies were discovered. The majority of recovered victims, 150 bodies, were buried in three Halifax cemeteries, the largest being Fairview Lawn Cemetery followed by the nearby Mount Olivet and Baron de Hirsch cemeteries.[56] Much floating wreckage was also recovered with the bodies, many pieces of which can be seen today in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

Memorials

In many locations there are memorials to the dead of the Titanic. In Southampton, England a memorial to the engineers of the Titanic may be found in Andrews Park on Above Bar Street. Opposite the main memorial is a memorial to Wallace Hartley and the other musicians who played on the Titanic. A memorial to the ship's five postal workers, which says "Steadfast in Peril" is held by Southampton Heritage Services.[57]

A memorial to the liner is also located on the grounds of City Hall in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

In the United States there are memorials to the Titanic disaster as well. The Titanic Memorial in Washington, D.C. and a memorial to Ida Straus at Straus Park in Manhattan, New York are two examples.

On 15 April 2012, the 100th anniversary of the sinking of Titanic is planned to be commemorated around the world. By that date, the Titanic Quarter in Belfast is planned to have been completed. The area will be regenerated and a signature memorial project unveiled to celebrate Titanic and her links with Belfast, the city that had built the ship.[58]

The Balmoral, operated by Fred Olsen Cruise Lines has been chartered by Miles Morgan Travel to follow the original route of the Titanic, intending to stop over the point on the sea bed where she rests on 15 April 2012.[59]

Investigations into the RMS Titanic disaster

Before the survivors even arrived in New York, investigations were being planned to discover what had happened, and what could be done to prevent a recurrence. The United States Senate initiated an inquiry into the disaster on 19 April, a day after Carpathia arrived in New York.

The chairman of the inquiry, Senator William Alden Smith, wanted to gather accounts from passengers and crew while the events were still fresh in their minds. Smith also needed to subpoena the British citizens while they were still on American soil. This prevented all surviving passengers and crew from returning to England before the American inquiry, which lasted until 25 May, was completed.

Lord Mersey was appointed to head the British Board of Trade's inquiry into the disaster. The British inquiry took place between 2 May and 3 July. Each inquiry took testimony from both passengers and crew of the Titanic, crew members of Leyland Line's Californian, Captain Arthur Rostron of the Carpathia and other experts.

The investigations found that many safety rules were simply out of date, and new laws were recommended. Numerous safety improvements for ocean-going vessels were implemented, including improved hull and bulkhead design, access throughout the ship for egress of passengers, lifeboat requirements, improved life-vest design, the holding of safety drills, better passenger notification, radio communications laws, etc. The investigators also learned that the Titanic had sufficient lifeboat space for all first-class passengers, but not for the lower classes. In fact, most third-class, or steerage, passengers had no idea where the lifeboats were, much less any way of getting up to the higher decks where the lifeboats were stowed.

SS Californian inquiry

Both inquiries into the disaster found that the SS Californian and its captain, Stanley Lord, failed to give proper assistance to the Titanic. Testimony before the inquiry revealed that at 22:10, the Californian observed the lights of a ship to the south; it was later agreed between Captain Lord and Third Officer C.V. Groves (who had relieved Lord of duty at 22:10) that this was a passenger liner. The Californian warned the ship by radio of the pack ice because of which the Californian had stopped for the night, but was violently rebuked by Titanic senior wireless operator, Jack Phillips. At 23:50, the officer had watched this ship's lights flash out, as if the ship had shut down or turned sharply, and that the port light was now observed. Morse light signals to the ship, upon Lord's order, occurred five times between 23:30 and 01:00, but were not acknowledged. (In testimony, it was stated that the Californian's Morse lamp had a range of about four miles (6 km), so could not have been seen from Titanic.)[37]

Captain Lord had retired at 23:30; however, Second Officer Herbert Stone, now on duty, notified Lord at 01:15 that the ship had fired a rocket, followed by four more. Lord wanted to know if they were company signals, that is, coloured flares used for identification. Stone said that he did not know that the rockets were all white. Captain Lord instructed the crew to continue to signal the other vessel with the Morse lamp, and went back to sleep. Three more rockets were observed at 01:50 and Stone noted that the ship looked strange in the water, as if she were listing. At 02:15, Lord was notified that the ship could no longer be seen. Lord asked again if the lights had had any colours in them, and he was informed that they were all white.

The Californian eventually responded. At 05:30, Chief Officer George Stewart awakened wireless operator Cyril Evans, informed him that rockets had been seen during the night, and asked that he try to communicate with any ships. The Frankfurt notified the operator of the Titanic's loss, Captain Lord was notified, and the ship set out for assistance.

The inquiries found that the Californian was much closer to the Titanic than the 19.5 miles (31.4 km) that Captain Lord had believed and that Lord should have awakened the wireless operator after the rockets were first reported to him, and thus could have acted to prevent loss of life.[37]

In 1990, following the discovery of the wreck, the Marine Accident Investigation Branch of the British Department of Transport re-opened the inquiry to review the evidence relating to the Californian. Its report of 1992 concluded that the Californian was farther from the Titanic than the earlier British inquiry had found, and that the distress rockets, but not the Titanic herself, would have been visible from the Californian.[60]

Rediscovery of the Titanic

The idea of finding the wreck of Titanic, and even raising the ship from the ocean floor, had been around since shortly after the ship sank. No attempts were successful until 1 September 1985, when a joint American-French expedition, led by Jean-Louis Michel (Ifremer) and Dr. Robert Ballard (WHOI), located the wreck using the side-scan sonar from the research vessel Knorr. It was found at a depth of 2.5 miles (4 km), slightly more than 370 miles (600 km) south-east of Mistaken Point, Newfoundland at 41°43′55″N 49°56′45″W / 41.73194°N 49.94583°W, 13 miles (21 km) from fourth officer Joseph Boxhall's last position reading where Titanic was originally thought to rest. Ballard noted that his crew had paid out 12,500 feet (3,810 m) of the sonar's tow cable at the time of the discovery of the wreck,[61] giving an approximate depth of the seabed of 12,450 feet (3,795 m).[62] Ifremer, the French partner in the search, records a depth of 3,800 m (12,467 ft), an almost exact equivalent.[63] These are approximately 2.33 miles, and they are often rounded upwards to 2.5 miles or 4 km. In 1986, Ballard returned to the wreck site aboard the Atlantis II to conduct the first manned dives to the wreck in the submersible Alvin.

Ballard had in 1982 requested funding for the project from the US Navy, but this was provided only on the then secret condition that the first priority was the then secret search for the sunken US nuclear submarines Thresher and Scorpion. Only when these had been discovered and photographed did the search for Titanic begin.[64]

The most notable discovery the team made was that the ship had split apart, the stern section lying 1,970 feet (600 m) from the bow section and facing opposite directions. There had been conflicting witness accounts of whether the ship broke apart or not, and both the American and British inquiries found that the ship sank intact. Up until the discovery of the wreck, it was generally assumed that the ship did not break apart.

The bow section had struck the ocean floor at a position just under the forepeak, and embedded itself 60 feet (18 m) into the silt on the ocean floor. Although parts of the hull had buckled, the bow was mostly intact. The collision with the ocean floor forced water out of Titanic through the hull below the well deck. One of the steel covers (reportedly weighing approximately ten tonnes) was blown off the side of the hull. The bow is still under tension, in particular the heavily damaged and partially collapsed decks.[65]

The stern section was in much worse condition, and appeared to have been torn apart during its descent. Unlike the bow section, which was flooded with water before it sank, it is likely that the stern section sank with a significant volume of air trapped inside it. As it sank, the external water pressure increased but the pressure of the trapped air could not follow suit due to the many air pockets in relatively sealed sections. Therefore, some areas of the stern section's hull experienced a large pressure differential between outside and inside which possibly caused an implosion. Further damage was caused by the sudden impact of hitting the seabed; with little structural integrity left, the decks collapsed as the stern hit.[66]

Surrounding the wreck is a large debris field with pieces of the ship, furniture, dinnerware and personal items scattered over one square mile (2.6 km²). Softer materials, like wood, carpet and human remains were devoured by undersea organisms.

Dr. Ballard and his team did not bring up any artefacts from the site, considering this to be tantamount to grave robbing.[67] Under international maritime law, however, the recovery of artefacts is necessary to establish salvage rights to a shipwreck. In the years after the find, Titanic has been the object of a number of court cases concerning ownership of artefacts and the wreck site itself. In 1994, RMS Titanic Inc. was awarded ownership and salvaging rights of the wreck, even though RMS Titanic Inc. and other salvaging expeditions have been criticised for taking items from the wreck. Among the items recovered by RMS Titanic Inc. was the ship's whistle, which was brought to the surface in 1992 and placed in the company's travelling exhibition. It has been operated only twice since, using compressed air rather than steam, because of its fragility.[68]

Approximately 6,000 artefacts have been removed from the wreck. Many of these were put on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, and later as part of a travelling museum exhibit.

Current condition of the wreck

Many scientists, including Robert Ballard, are concerned that visits by tourists in submersibles and the recovery of artefacts are hastening the decay of the wreck. Underwater microbes have been eating away at Titanic's iron since the ship sank, but because of the extra damage visitors have caused the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that "the hull and structure of the ship may collapse to the ocean floor within the next 50 years."[69][70]

Ballard's book Return to Titanic, published by the National Geographic Society, includes photographs depicting the deterioration of the promenade deck and damage caused by submersibles landing on the ship. The mast has almost completely deteriorated and has been stripped of its bell and brass light. Other damage includes a gash on the bow section where block letters once spelled Titanic, part of the brass telemotor which once held the ship's wooden wheel is now twisted and the crow's nest is completely deteriorated.[71]

Ownership and litigation

Titanic's rediscovery in 1985 launched a debate over ownership of the wreck and the valuable items inside. On 7 June 1994 RMS Titanic Inc., a subsidiary of Premier Exhibitions Inc., was awarded ownership and salvaging rights by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.[72] (See Admiralty law)[73] Since 1987, RMS Titanic Inc. and its predecessors have conducted seven expeditions and salvaged over 5,500 historic objects. The biggest single recovered object was a 17-ton section of the hull, recovered in 1998.[74] Many of these items are part of travelling museum exhibitions.

In 1993, a French administrator in the Office of Maritime Affairs of the Ministry of Equipment, Transportation, and Tourism awarded RMS Titanic Inc.'s predecessor title to the relics recovered in 1987.

In a motion filed on 12 February 2004, RMS Titanic Inc. requested that the district court enter an order awarding it "title to all the artifacts (including portions of the hull) which are the subject of this action pursuant to the Law of Finds" or, in the alternative, a salvage award in the amount of $225 million. RMS Titanic Inc. excluded from its motion any claim for an award of title to the objects recovered in 1987, but it did request that the district court declare that, based on the French administrative action, "the artifacts raised during the 1987 expedition are independently owned by RMST." Following a hearing, the district court entered an order dated 2 July 2004, in which it refused to grant comity and recognise the 1993 decision of the French administrator, and rejected RMS Titanic Inc.'s claim that it should be awarded title to the items recovered since 1993 under the Maritime Law of Finds.

RMS Titanic Inc. appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. In its decision of 31 January 2006[75] the court recognised "explicitly the appropriateness of applying maritime salvage law to historic wrecks such as that of Titanic" and denied the application of the Maritime Law of Finds. The court also ruled that the district court lacked jurisdiction over the "1987 artifacts", and therefore vacated that part of the court's 2 July 2004 order. In other words, according to this decision, RMS Titanic Inc. has ownership title to the objects awarded in the French decision (valued $16.5 million earlier) and continues to be salver-in-possession of the Titanic wreck. The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the District Court to determine the salvage award ($225 million requested by RMS Titanic Inc.).[76]

On 24 March 2009, it was revealed that the fate of 5,900 artefacts retrieved from the wreck will rest with a US District Judge's decision.[77] The ruling will decide whether the artefacts should be placed in a public exhibit or in the hands of private collectors. The judge will also rule on the RMS Titanic Inc.'s degree of ownership of the wreck as well as establishing a monitoring system to check future activity upon the wreck site.[78]

Possible factors in the sinking

It is well established that the sinking of the Titanic was the result of an iceberg collision which fatally punctured the ship's front five watertight compartments. Less obvious however are the reasons for the collision itself (which occured on a clear night, and after the ship had received numerous ice warnings), the factors underlying the sheer extent of the damage sustained by the ship, and the reasons for the extreme loss of life.

Construction

Originally, historians thought the iceberg had cut a gash into Titanic's hull. Since the part of the ship that the iceberg damaged is now buried, scientists used sonar to examine the area and discovered the iceberg had caused the hull to buckle, allowing water to enter Titanic between her steel plates.

A detailed analysis of small pieces of the steel plating from the Titanic's wreck hull found that it was of a metallurgy that loses its elasticity and becomes brittle in cold or icy water, leaving it vulnerable to dent-induced ruptures. The pieces of steel were found to have very high content of phosphorus and sulphur (4x and 2x respectively, compared with modern steel), with manganese-sulphur ratio of 6.8:1 (compared with over 200:1 ratio for modern steels). High content of phosphorus initiates fractures, sulphur forms grains of iron sulphide that facilitate propagation of cracks, and lack of manganese makes the steel less ductile. The recovered samples were found to be undergoing ductile-brittle transition in temperatures of 90 °F (32 °C) for longitudinal samples and 133 °F (56 °C) for transversal samples, compared with transition temperature of −17 °F (−27 °C) common for modern steels: modern steel would only become so brittle in between −76 °F and −94 °F (−60 °C and −70 °C). The Titanic's steel, although "probably the best plain carbon ship plate available at the time", was thus unsuitable for use at low temperatures.[79] The anisotropy was probably caused by hot rolling influencing the orientation of the sulphide stringer inclusions. The steel was probably produced in the acid-lined, open-hearth furnaces in Glasgow, which would explain the high content of phosphorus and sulphur, even for the time.[79][80]

Another factor was the rivets holding the hull together, which were much more fragile than once thought.[80][81] From 48 rivets recovered from the hull of the Titanic, scientists found many to be riddled with high concentrations of slag. A glassy residue of smelting, slag can make rivets brittle and prone to fracture. Records from the archive of the builder show that the ship's builder ordered No. 3 iron bar, known as "best" — not No. 4, known as "best-best", for its rivets, although shipbuilders at that time typically used No. 4 iron for rivets. The company also had shortages of skilled riveters, particularly important for hand riveting, which took great skill: the iron had to be heated to a precise colour and shaped by the right combination of hammer blows. The company used steel rivets, which were stronger and could be installed by machine, on the central hull, where stresses were expected to be greatest, using iron rivets for the stern and bow.[80] Rivets of "best best" iron had a tensile strength approximately 80% of that of steel, "best" iron some 73%.[82] Despite this, the most extensive and finally fatal damage Titanic sustained at boiler rooms No. 5 & 6 was done in an area where steel rivets were used.

Rudder construction and turning ability

Although Titanic's rudder met the mandated dimensional requirements for a ship her size, the rudder's design was hardly state-of-the-art. According to research by BBC History: "Her stern, with its high graceful counter and long thin rudder, was an exact copy of an 18th-century sailing ship...a perfect example of the lack of technical development. Compared with the rudder design of the Cunarders, Titanic's was a fraction of the size. No account was made for advances in scale and little thought was given to how a ship, 852 feet in length, [sic] might turn in an emergency or avoid collision with an iceberg. This was Titanic's Achilles heel."[83] A more objective assessment of the rudder provision compares it with the legal requirement of the time: the area had to be within a range of 1.5% and 5% of the hull's underwater profile and, at 1.9%, the Titanic was at the low end of the range. However, the tall rudder design was more effective at the vessel's designed cruising speed; short, square rudders were more suitable for low-speed manoeuvring.[84]

Perhaps more fatal to the design of the Titanic was her triple screw engine configuration, which had reciprocating steam engines driving her wing propellers, and a steam turbine driving her centre propeller. The reciprocating engines were reversible, while the turbine was not. According to subsequent evidence from Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall, who entered the bridge just after the collision, First Officer Murdoch had set the engine room telegraph to reverse the engines to avoid the iceberg,[33] thus handicapping the turning ability of the ship. Because the centre turbine could not reverse during the "full speed astern" manoeuvre, it was simply stopped. Since the centre propeller was positioned forward of the ship's rudder, the effectiveness of that rudder would have been greatly reduced: had Murdoch simply turned the ship while maintaining her forward speed, the Titanic might have missed the iceberg with metres to spare.[85] Another survivor, Frederick Scott, an engine room worker, gave contrary evidence: he recalled that at his station in the engine room all four sets of telegraphs had changed to "Stop", but not until after the collision.[34]

Orientation of impact

It has been speculated that the ship could have been saved if she had rammed the iceberg head on.[86][87] It is hypothesised that if Titanic had not altered her course at all and instead collided head first with the iceberg, the impact would have been taken by the naturally stronger bow and damage would have affected only one or two forward compartments. This would have disabled her, and possibly caused casualties among the passengers near the bow, but probably would not have resulted in sinking since Titanic was designed to float with the first four compartments flooded. Instead, the glancing blow to the starboard side caused buckling in the hull plates along the first five compartments, more than the ship's designers had allowed for.

Adverse weather conditions

The weather conditions for the Atlantic at the time of the collision were unusual because there was a flat calm sea, without wind or swell. In addition, it was a moonless night. Under normal sea conditions in the area of the collision, waves would have broken over the base of an iceberg, assisting in the location of icebergs even on a moonless night.

Excessive speed

The conclusion of the British Inquiry into the sinking was “that the loss of the said ship was due to collision with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship was being navigated”. At the time of the collision it is thought that the Titanic was at her normal cruising speed of about 22 knots, which was less than her top speed of around 24 knots. At the time it was common (but not universal) practice to maintain normal speed in areas where icebergs were expected. It was thought that any iceberg large enough to damage the ship would be seen in sufficient time to be avoided.

After the sinking the British Board of Trade introduced regulations instructing vessels to moderate their speed if they were expecting to encounter icebergs.[citation needed] It is often alleged that J. Bruce Ismay instructed or encouraged Captain Smith to increase speed in order to make an early landfall, and it is a common feature in popular representations of the disaster, such as the 1997 film, Titanic [88] There is little evidence for this having happened, and it is disputed by many.[89][90]

Insufficient lifeboats

No single aspect regarding the huge loss of life from the Titanic disaster has provoked more outrage than the fact that the ship did not carry enough lifeboats for all her passengers and crew. This is partially due to the fact that the law, dating from 1894, required a minimum of 16 lifeboats for ships of over 10,000 tons. This law had been established when the largest ship afloat was RMS Lucania. Since then the size of ships had increased rapidly, meaning that Titanic was legally required to carry only enough lifeboats for less than half of its capacity. Actually, the White Star Line exceeded the regulations by including four more collapsible lifeboats — this gave a total capacity of 1,178 people (still only around a third of Titanic's total capacity of 3,547).

In the busy North Atlantic sea lanes it was expected that in the event of a serious accident to a ship, help from other vessels would be quickly obtained, and that the lifeboats would be used to ferry passengers and crew from the stricken vessel to its rescuers. Full provision of lifeboats was not considered necessary for this.

It was anticipated during the design of the ship that the British Board of Trade might require an increase in the number of lifeboats at some future date. Therefore lifeboat davits capable of handling up to four boats per pair of davits were designed and installed, to give a total potential capacity of 64 boats[91]. The additional boats were never fitted. It is often alleged that J. Bruce Ismay, the President of White Star, vetoed the installation of these additional boats to maximise the passenger promenade area on the boat deck. Harold Sanderson, Vice President of International Merchantile Marine refuted this allegation during the British Inquiry.[92]

The lack of lifeboats was not the only cause of the tragic loss of lives. After the collision with the iceberg, one hour was taken to evaluate the damage, recognize what was going to happen, inform first class passengers, and lower the first lifeboat. Afterward, the crew worked quite efficiently, taking a total of 80 minutes to lower all 16 lifeboats. Since the crew was divided into two teams, one on each side of the ship, an average of 10 minutes of work was necessary for a team to fill a lifeboat with passengers and lower it.

Yet another factor in the high death toll that related to the lifeboats was the reluctance of the passengers to board them. They were, after all, on a ship deemed to be "unsinkable". Because of this, some lifeboats were launched with far less than capacity, the most notable being Lifeboat #1, with a capacity of 40, launched with only 12 people aboard.

Alternative theories

A number of alternative theories diverging from the standard explanation for the Titanic's demise have been brought forth since shortly after the sinking. Some of these include a coal fire aboard ship,[93] or the Titanic hitting pack ice rather than an iceberg.[94][95] In the realm of the supernatural, it has been proposed that the Titanic sank due to a mummy's curse.[96]

Legends and myths regarding the RMS Titanic

Unsinkable

Contrary to popular mythology, the Titanic was never described as "unsinkable", without qualification, until after she sank.[6][97] There are three trade publications (one of which was probably never published) that describe the Titanic as unsinkable, prior to its sinking, but there is no evidence that the notion of the Titanic's unsinkability had entered public consciousness until after the sinking.[6]

The first unqualified assertion of the Titanic's unsinkability appears the day after the tragedy (on 16 April 1912) in The New York Times, which quotes Philip A. S. Franklin, vice president of the White Star Line as saying, when informed of the tragedy,

I thought her unsinkable and I based by [sic] opinion on the best expert advice available. I do not understand it.[98]

This comment was seized upon by the press and the idea that the White Star Line had previously declared the Titanic to be unsinkable (without qualification) gained immediate and widespread currency.

David Sarnoff, wireless reports and the use of SOS

An often-quoted story that has been blurred between fact and fiction states that the first person to receive news of the sinking was David Sarnoff, who would later lead media giant RCA. In modified versions of this legend, Sarnoff was not the first to hear the news (though Sarnoff willingly promoted this notion), but he and others did staff the Marconi wireless station (telegraph) atop the Wanamaker Department Store in New York City, and for three days, relayed news of the disaster and names of survivors to people waiting outside. However, even this version lacks support in contemporary accounts. No newspapers of the time, for example, mention Sarnoff. Given the absence of primary evidence, the story of Sarnoff should be properly regarded as a legend.[99][100][101][102][103]

Despite popular belief, the sinking of Titanic was not the first time the internationally recognised Morse code distress signal "SOS" was used. The SOS signal was first proposed at the International Conference on Wireless Communication at Sea in Berlin in 1906. It was ratified by the international community in 1908 and had been in widespread use since then. The SOS signal was, however, rarely used by British wireless operators, who preferred the older CQD code. First Wireless Operator Jack Phillips began transmitting CQD until Second Wireless Operator Harold Bride suggested half jokingly, "Send SOS; it's the new call, and this may be your last chance to send it." Phillips, who later died, then began to intersperse SOS with the traditional CQD call.

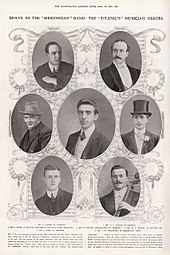

Titanic's band

One of the most famous stories of Titanic is of the band. On 15 April Titanic's eight-member band, led by Wallace Hartley, had assembled in the first-class lounge in an effort to keep passengers calm and upbeat. Later they moved on to the forward half of the boat deck. The band continued playing, even when it became apparent the ship was going to sink, and all members perished.

There has been much speculation about what their last song was. A first-class Canadian passenger, Mrs. Vera Dick, alleged that the final song played was the hymn "Nearer, My God, to Thee". Hartley reportedly once said to a friend if he were on a sinking ship, "Nearer, My God, to Thee" would be one of the songs he would play.[104] But Walter Lord's book A Night to Remember popularized wireless operator Harold Bride's 1912 account (New York Times) that he heard the song "Autumn" before the ship sank. It is considered Bride either meant the hymn called "Autumn" or waltz "Songe d'Automne" but neither were in the White Star Line songbook for the band.[104] Bride is the only witness who was close enough to the band, as he floated off the deck before the ship went down, to be considered reliable—Mrs. Dick had left by lifeboat an hour and 20 minutes earlier and could not possibly have heard the band's final moments. The notion that the band played "Nearer, My God, to Thee" as a swan song is possibly a myth originating from the wrecking of the SS Valencia, which had received wide press coverage in Canada in 1906 and so may have influenced Mrs. Dick's recollection.[6] Also, there are two, very different, musical settings for "Nearer, My God, to Thee": one is popular in Britain, and the other is popular in the U.S., and the British melody might sound like the other hymn ("Autumn"). The film A Night to Remember (1958) uses the British setting; while the 1953 film Titanic, with Clifton Webb, uses the American setting; but Cameron's Titanic (1997) has passengers singing the hymn "Autumn" as only Harold Bride indicated.[104]

The Predictions of W.T. Stead

Another often cited Titanic legend concerns perished first class passenger William Thomas Stead. According to this folklore, Stead had, through precognative insight, foreseen his own death on the Titanic. This is apparently suggested in two fictional sinking stories, which he penned decades earlier. The first, "How the Mail Steamer Went Down in Mid-Atlantic, by a Survivor" [105] (Pall Mall Gazette, March 22, 1886) tells of a mail steamer's collision with another ship, resulting in high loss of life due to lack of lifeboats. Cryptically, Stead finishes the story: "This is exactly what might take place and will take place if liners are sent to sea short of boats".

The Titanic curse

When Titanic sank, claims were made that a curse existed on the ship. The press quickly linked the "Titanic curse" with the White Star Line practice of not christening their ships (notwithstanding the opening scene of the film A Night to Remember).[6]

One of the most widely spread legends linked directly into the sectarianism of the city of Belfast, where the ship was built. It was suggested that the ship was given the number 390904 which, when read backwards as reflected by the water's surface, was claimed to spell 'no pope', a sectarian slogan attacking Roman Catholics that was (and is) widely used provocatively by extreme Protestants in Northern Ireland, where the ship was built. In the extreme sectarianism of north-east Ireland (Northern Ireland itself did not exist until 1920), the ship's sinking, though mourned, was alleged to be on account of the sectarian anti-Catholicism of her manufacturers, the Harland and Wolff company, which had an almost exclusively Protestant workforce and an alleged record of hostility towards Catholics. (Harland and Wolff did have a record of hiring few Catholics; whether that was through policy or because the company's shipyard in Belfast's bay was located in almost exclusively Protestant East Belfast — through which few Catholics would dare to travel — or a mixture of both, is a matter of dispute.)[106]

The 'no pope' story is in fact an urban legend. RMS Olympic and Titanic were assigned the yard numbers 400 and 401[107] respectively. The source of the story may have been from reports by dockworkers in Queenstown of anti-Catholic graffiti that they found on Titanic's coalbunkers when they were loading coal.

See also

- List of films about the RMS Titanic

- MS Hans Hedtoft, a ship sunk by an iceberg on her maiden voyage in 1959.

- Futility, or the Wreck of the Titan, a novella written by Morgan Robertson that outlined events similar to that of the Titanic, fourteen years prior to her sinking.

- SS Nomadic, former tender to the Titanic and Olympic.

References

Explanatory notes

a. ^ Times given are in ship time, the local time for Titanic's position in the Atlantic. On the night of the sinking, this was approximately one and half hours ahead of EST and two hours behind GMT.

Notes

- ^ Wilson, Timothy (1986). "Flags of British Ships other than the Royal Navy". Flags at Sea. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 34. ISBN 0-11-290389-4.

- ^ Maritimequest: RMS Titanic's data

- ^ a b c d Staff (27 May 1911). "The Olympic and Titanic". The Times (39596). London: 4.

- ^ a b Beveridge, Bruce (2004). "Ismay's Titans". Olympic & Titanic. West Conshohocken, PA: Infinity. p. 1. ISBN 0741419491.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic-Class Ships. Stroud, England: Tempus. p. 43. ISBN 0752428683.

- ^ a b c d e Richard Howells The Myth of the Titanic, ISBN 0333725972

- ^ Moss, Michael S (2004). "William James Pirrie". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bullock, Shan F. (1912). Thomas Andrews, Shipbuilder. Dublin: Maunsel and Co.

- ^ Jenkins, Stanley C. (1926-03-06). "Alexander Carlisle Obituary". The Times. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ a b "Testimony of Alexander Carlisle". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "RMS Titanic facts".

- ^ "Titanic:A voyage of discovery".

- ^ "Titanic-construction".

- ^ "Wireless and the Titanic".

- ^ LaRoe, L. M. n.d. Titanic. National Geographic Society Society.

- ^ "Titanic's life saving appliances". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ "Alexander Carlisle's testimony (question 21449)". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ Butler, p. 38

- ^ "Board of Trade's Administration". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "Testimony of J. Bruce Ismay". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Testimony of Harold A. Sanderson, recalled". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ^ "Titanic's Blueprints [Roy Mengot] db-09". Titanic-model.com. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ Titanic's Sea Trials

- ^ Cableto THE NEW YORK TIMES., Special (1912-04-11). "TITANIC IN PERIL ON LEAVING PORT". New York Times (1857-Current file). p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- ^ "Titanic Passengers and Crew Listings". encyclopedia titanica. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ "Deep Ocean Expeditions.com". Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ a b "Titanic Passenger List First Class Passengers". Encyclopedia Titanica. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Chernow (2001) Chapter 8

- ^ "Titanic & Her Sisters Olympic & Britannic" by McCluskie/Sharpe/Marriott, p. 490, ISBN 1-57145-175-7

- ^ "Unsinkable - the Full Story" by Daniel Allen Butler, pp. 61-62, ISBN 0-8117-1814-X

- ^ "The Discovery of the Titanic" by Dr. Ballard, p. 20, ISBN 0-446-51385-7

- ^ titanic.marconigraph.com - STOP Command Greaser Frederick Scott, who stated that the engine-room telegraphs showed "Stop", and by Leading Stoker Frederick Barrett who stated that the stoking indicators went from “Full” to “Stop”

- ^ a b "Testimony of Joseph G. Boxhall". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ a b "Testimony of Frederick Scott". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ a b "Pleas For Help - Distress Calls Heard". United States Senate Inquiry Report. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ http://www.webtitanic.net/framecal.html

- ^ a b c d "STEAMSHIP LIGHT SEEN FROM STEAMSHIP TITANIC & STEAMSHIP CALIFORNIAN'S RESPONSIBILITY". United States Senate Inquiry Report. Titanic Inquiry Project. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ United States Senate Inquiry - Day 8: Testimony of Cyril F. Evans

- ^ http://home.comcast.net/~bwormst/titanic/lifeboats/lifeboats.htm

- ^ http://www.titanic-titanic.com/lifeboat_lowering_times.shtml

- ^ ""RMS Carpathia"". Retrieved 2008-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Holdaway, F. W. (19 April 1912). "Winchester "titanic relief fund"". The Hampshire Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Gloom in southampton". The Hampshire Chronicle. 1912. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ U.S. Senate inquiry stats

- ^ Spitz, D.J. (2006): Investigation of Bodies in Water. In: Spitz, W.U. & Spitz, D.J. (eds): Spitz and Fisher’s Medicolegal Investigation of Death. Guideline for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigations (Fourth edition), Charles C. Thomas, pp.: 846-881; Springfield, Illinois.

- ^ Titanic Disaster: Official Casualty Figures and Commentary

- ^ Be British boys

- ^ Frey, Bruno S.; Savage, David A.; Torgler, Benno (January 2009), Surviving The Titanic Disaster: Economic, Natural And Social Determinants (PDF), Basel, Switzerland: Center for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts

- ^ Pålsson family tragedy

- ^ "Last Titanic survivor dies at 97". BBC News. 2009-05-31. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ^ Dogs on the Titanic

- ^ "RMS Titanic: List of Bodies and Disposition of Same". Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ a b "TITANIC - A Voyage of Discovery"

- ^ Maritime Museum of the Atlantic Titanic Research Page - Victims

- ^ Mowbray, Jay Henry (1912). "CHAPTER XXI. THE FUNERAL SHIP AND ITS DEAD". The sinking of the Titanic (1912). Retrieved 24 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ruffman, Alan Titanic Remembered: The Unsinkable ship and Halifax (1999) Halifax: Formac Publishing

- ^ The British Postal Museum & Archive online catalogue

- ^ "Titanic tourist project unveiled". BBC News. 2005-08-11.

- ^ "Cruise to mark Titanic centenary". BBC News. 2009-04-15.

- ^ Marine Accident Investigation Branch. (1992). RMS Titanic Reappraisal of Evidence Relating to SS Californian. London: H.M.S.O. ISBN 0115511113.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ballard, Robert D. (1988). The Discovery of the Titanic. Toronto: Madison Press. ISBN 0-670-81917-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 150" ignored (help) - ^ Staff (2004-01-01). "1985 Discovery of Titanic". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ^ "Mise au point du Système Acoustique Remorqué (Deployment of the Towed Acoustic System)" (Press release) (in French). Ifremer. 2004-11-23. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ^ Smith, Lewis (2008-05-24). "Titanic search was cover for secret Cold War subs mission". The Times. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ Lynch, Marschall & Cameron 2003, p. 137.

- ^ Serway, Raymond A. (2005). Principles Of Physics. Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 053449143X.

{{cite book}}: Text "pp. 494–495" ignored (help) - ^ Howells, Richard (1999). The myth of the Titanic. Basingstoke, England: Macmillan. p. 35. ISBN 0-333-72597-2.

- ^ "Titanic's whistles". Titanic-Titanic.com. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ^ Duncan Crosbie & Sheila Mortimer: Titanic: The Ship of Dreams, last page (no page number specified). Tony Potter Publishing Ltd., 2008

- ^ http://titanic.marconigraph.com/mgy_05observations.html, Last paragraph (Conclusion)

- ^ National Geographic Magazine: Why is Titanic Vanishing?

- ^ Comprehensive resume of ownership questions

- ^ "Corporate Profile". RMS Titanic, Inc. Retrieved 1 February 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Expeditions". RMS Titanic, Inc. Retrieved 1 February 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Template:PDFlink

- ^ "Commented excerpts of the Court of Appeals decision".

- ^ http://www.lehighvalleylive.com/entertainment-general/index.ssf/2009/03/battle_continues_on_fate_of_re.html

- ^ http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2009-03-24-titanic-artifacts_N.htm

- ^ a b Felkins, Katherine (1998). "The Royal Mail Ship Titanic: Did a Metallurgical Failure Cause a Night to Remember?". JOM. 50 (1). Warrendale PA: The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society: 12. doi:10.1007/s11837-998-0062-7. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "pp. 12–18" ignored (help) - ^ a b c In Weak Rivets, a Possible Key to Titanic’s Doom, New York Times, 15 April 2008. A1-A21.

- ^ McCarty, Jennifer et al. (2008). What Really Sank the Titanic. New York: Citadel Books.

- ^ Adams, Henry (1907). Cassel's Engineers' Handbook. London: Cassel and Company Ltd.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|unused_data=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|p.=ignored (help) - ^ Louden-Brown, Paul (2002-04-01). "Titanic: Sinking the Myths". British History. BBC. Retrieved 2005-06-20. The length quoted approximates to the vessel's waterline length.

- ^ Brown, David G. (2000). The Last Log of the Titanic. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0071364471.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "pp. 65–77; 111–112" ignored (help) - ^ Barczewski, Stephanie (2006). Titanic: A Night Remembered. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1852855002.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 194" ignored (help) - ^ Cassidy, Michael J. (2003). "The Sinking of the Titanic". In Hall, Randolph W. (ed.). Handbook of Transportation Science. Amsterdam Netherlands: Kluwer. ISBN 1402072465.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 68" ignored (help) - ^ "Testimony of Edward Wilding". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. 1912-07-30. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ "Titanic quotes from IMDB".

- ^ Beesley, Lawrence (1912). The Loss of the S.S. Titanic. London: Heinemann. p. 56.

- ^ Howells (1999: 31)

- ^ Testimony of Alexander Carlisle at British Inquiry

- ^ Testimony of Harold Sanderson at British Inquiry - Question #19398

- ^ Coal Fire Theory

- ^ Efforts to solve Titanic mystery cut no ice

- ^ L. M. Collins, The Sinking of the Titanic: The Mystery Solved

- ^ John P. Eaton, Charles A. Haas, Titanic: Destination Disaster: the Legends and the Reality, p. 95

- ^ Staff (19 April 1912). "Lead Article". The Engineer.

The phrase 'unsinkable ships' is certainly not one that has originated from the builders

- ^ Staff (16 April 1912). "Titanic sinks four hours after hitting iceberg". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

{{cite news}}: Text "pp. 1-2" ignored (help) - ^ "More About Sarnoff, Part One". PBS.

- ^ Bruce M. Owen (1999). "The Evolution of Broadcast Radio". The Internet Challenge to Television. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674003896.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 55" ignored (help) - ^ Albert Abramson (1995). "An Invitation from Westinghouse". Zworykin, Pioneer of Television. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252021045.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 41" ignored (help) - ^ Harold Evans (2006). They Made America: From the Steam Engine to the Search Engine. Little Brown And Company. ISBN 0316277665.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 337" ignored (help) - ^ Huntington Williams (1989). Beyond Control: ABC and the Fate of the Networks. Atheneum. ISBN 068911818X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "p. 26" ignored (help) - ^ a b c "snopes.com: Last Song on the Titanic", December 2005, web: T-lastsong.

- ^ W.T. Stead, "How the Mail Steamer went down in Mid Atlantic" (1886) at www.attackingthedevil.co.uk

- ^ "Pope and Circumstance". www.snopes.com. 2005-12-15. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Mark Chirnside (2008-05-05). "The mystery of Titanic's central propeller". Retrieved 2009-01-08.

Bibliography

- Beesley, Lawrence, The Loss of the SS Titanic: Its Story and Its Lessons, by One of the Survivors (June, 1912)

- Brander, Roy. The RMS Titanic and its Times: When Accountants Ruled the Waves. Elias P. Kline Memorial Lecture, October 1998 http://www.cuug.ab.ca/~branderr/risk_essay/Kline_lecture.html

- Brown, David G. (2000). The Last Log of the Titanic. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0071364471.

- Butler, Daniel Allen. Unsinkable: The Full Story of RMS Titanic. Stackpole Books, 1998, 292 pages

- Collins, L. M. The Sinking of the Titanic: The Mystery Solved Souvenir Press, 2003 ISBN 0-285-63711-8

- Eaton, John P. and Haas, Charles A. Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy (2nd ed.). W.W. Norton & Company, 1995 ISBN 0-393-03697-9

- Eaton, John P. and Haas, Charles A. Falling Star: The Misadventures of White Star Line Ships, c. 1990 W.W. Norton & Company, 1990 ISBN 0-3930-2873-7

- Gardener, R & van der Vat, D The Riddle of the Titanic Orion 1995

- HMSO. The Loss Of The Titanic: 1912 ISBN 0-11-702403-1 (Republished version of Lord Mersey's final report of the British inquiry, also including the report of 1992 inquiry)

- Kentley, Eric. Discover the Titanic Ed. Claire Bampton and Sue Leonard. 1st ed. New York: DK, Inc., 1997. 22. ISBN 0-7894-2020-1