Religious views of Thomas Jefferson

The religious views of Thomas Jefferson diverged widely from the orthodox Christianity of his era. Throughout his life Jefferson was intensely interested in theology, religious studies, and morality.[1] Jefferson was most closely connected with Unitarianism.[2] He was sympathetic to and in general agreement with the moral precepts of Christianity, believed in an afterlife[3] and in the active involvement, or guidance, of God in the affairs of mankind.[4] He considered the teachings of Jesus as having "the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man,"[5] yet he held that the pure teachings of Jesus appeared to have been appropriated by some of Jesus' early followers, resulting in a Bible that contained both "diamonds" of wisdom and the "dung" of ancient political agendas.[6]

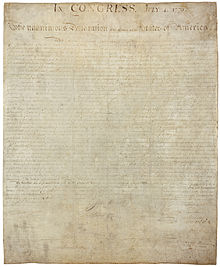

As the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence, Jefferson articulated a statement about human rights that most Americans regard as nearly sacred. Jefferson held that "acknowledging and adoring an overruling providence" (as in his First Inaugural Address[7]) was important and in his second inaugural address, expressed the need to gain "the favor of that Being in whose hands we are, who led our fathers, as Israel of old."[4] Still, together with James Madison, Jefferson carried on a long and successful campaign against state financial support of churches in Virginia. Also, it is Jefferson who coined the phrase "wall of separation between church and state" in his 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptists of Connecticut. During his 1800 campaign for the presidency, Jefferson even had to contend with critics who argued that he was unfit to hold office because of their discomfort with his "unorthodox" religious beliefs.

Jefferson used certain passages of the New Testament to compose The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (the "Jefferson Bible"), which excluded any miracles by Jesus and stressed his moral message. Though he often expressed his opposition to many practices of the clergy, and to many specific popular Christian doctrines of his day, Jefferson repeatedly expressed his admiration for Jesus as a moral teacher, and consistently referred to himself as a Christian (though following his own unique type of Christianity) throughout his life. Jefferson opposed Calvinism, Trinitarianism, and what he identified as Platonic elements in Christianity. In private letters Jefferson also described himself as subscribing to other certain philosophies, in addition to being a Christian. In these letters he described himself as also being an "Epicurean" (1819),[8] a "19th century materialist" (1820),[9] a "Unitarian by myself" (1825),[10] and "a sect by myself" (1819).[11] Upon the disestablishment of religion in Connecticut, he wrote to John Adams: "I join you, therefore, in sincere congratulations that this den of the priesthood is at length broken up, and that a Protestant Popedom is no longer to disgrace the American history and character."[12]

Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom associated Jefferson with "rational religion" or deism,[13] however Jefferson's expressed beliefs in divine interventionism, and in an afterlife would seem to disqualify him from being labeled as a true Deist, as the word Deist is understood in modern-day usage. Jefferson saw a certain harmony between the various philosophies that he ascribed to, but his understandings of these philosophies themselves were sometimes at odds with the more popular or "orthodox" understandings of these philosophies of his day.

Church attendance

Jefferson was raised in the Church of England at a time when it was the established church in Virginia and only denomination funded by Virginia tax money. Before the Revolution, parishes were units of local government, and Jefferson served as a vestryman, a lay administrative position in his local parish. Office-holding qualifications at all levels—including the Virginia House of Burgesses, to which Jefferson was elected in 1769—required affiliation with the current state religion and a commitment that one would neither express dissent nor do anything that did not conform to church doctrine. Jefferson counted clergy among his friends, and he contributed financially to the Anglican Church he attended regularly.

Following the Revolution, the Church of England in America was disestablished. It reorganized as the Episcopal Church in America. Margaret Bayard Smith, whose husband was a close friend of Jefferson, records that during the first winter of Jefferson's Presidency he regularly attended service on Sunday in a small humble Episcopalian church out of respect for public worship. This was the only church in the new city, with the exception of a little Catholic chapel. Within a year of his inauguration, Jefferson began attending church services in the House of Representatives, a custom which had not yet begun while he was Vice President, and which featured preachers of every Christian sect and denomination.[14]

In January 1806, a female evangelist, Dorothy Ripley, delivered a camp meeting-style exhortation in the House to Jefferson, Vice President Aaron Burr, and a "crowded audience". Throughout his administration Jefferson permitted church services in executive branch buildings, which were acceptable to Jefferson because they were nondiscriminatory and voluntary, and because he believed that religion was an important support for republican government.[15]

Henry S. Randall, the only biographer permitted to interview Jefferson's immediate family, recorded that Jefferson "attended church with as much regularity as most of the members of the congregation—sometimes going alone on horse-back, when his family remained at home", and that he also "contributed freely to the erection of Christian churches, gave money to Bible societies and other religious objects, and was a liberal and regular contributor to the support of the clergy. Letters of his are extant which show him urging, with respectful delicacy, the acceptance of extra and unsolicited contributions, on the pastor of his parish, on occasions of extra expense to the latter, such as the building of a house."[16]

In later years, Jefferson refused to serve as a godparent for infants being baptized, because he did not believe in the dogma of the Trinity.[17] Despite testimony of Jefferson's church attendance, there is no evidence that he was ever confirmed or was a communicant.[18]

Jefferson and Deism

While Jefferson did use the term Deism to describe Jesus' teachings, his usage of this term in this context may not have had exactly the same meaning as contemporary usage of the term "Deism" most typically implies today. Even though Jefferson did indeed reject the "miracles" and the "divinity" of Jesus, he still maintained a belief in an afterlife,[3] and in divine interventionism.[4] In modern-day understandings of Deism, "divine interventionism" is specifically opposed by Deism, and a belief in an afterlife is generally "tolerated" but certainly not a core tenet. Jefferson was never known to have described himself as a Deist.

In 1760, at age 16, Jefferson entered the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, and for two years he studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under Professor William Small. He introduced the enthusiastic Jefferson to the writings of the British Empiricists, including John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton.[19] Jefferson biographers say that he was influenced by deist philosophy while at William & Mary, particularly by Bolingbroke.[20][21]

Phrases such as "Nature's God", which Jefferson used in the Declaration of Independence, are typical of Deism, although they were also used at the time by non-Deist thinkers, such as Francis Hutcheson. In addition, it was part of Roman thinking about natural law, and Jefferson was influenced by reading Cicero on this topic.[22][23]

Most deists denied the Christian concepts of miracles and the Trinity. Though he had a lifelong esteem for Jesus' moral teachings, Jefferson did not believe in miracles, nor in the divinity of Jesus. In a letter to deRieux in 1788, he declined a request to act as a godfather, saying he had been unable to accept the doctrine of the Trinity "from a very early part of my life".[17][24]

Jefferson was directly linked to deism in the writings of some of his contemporaries. Patrick Henry's widow wrote in 1799, "I wish the Grate Jefferson & all the Heroes of the Deistical party could have seen my... Husband pay his last debt to nature."[25][26]

While many biographers, as well as some of his contemporaries, have characterized Jefferson as a Deist, historians and scholars have not found any such self-identification in Jefferson's surviving writings. In an 1803 letter to Priestley, Jefferson praises Jesus for a form of deism.[27] He expressed similar ideas in an 1817 letter to John Adams.[28]

Disestablishment of religion in Virginia

For Jefferson, separation of church and state was a necessary reform of the religious tyranny whereby a religion received state endorsement, and those not of that religion were denied rights, and even punished.

Following the Revolution, Jefferson played a leading role in the disestablishment of religion in Virginia. Previously as the established state church, the Anglican Church received tax support and no one could hold office who was not an Anglican. The Presbyterian, Baptist and Methodist churches did not receive tax support. As Jefferson wrote in his Notes on Virginia, pre-Revolutionary colonial law held that "if a person brought up a Christian denies the being of a God, or the Trinity ...he is punishable on the first offense by incapacity to hold any office ...; on the second by a disability to sue, to take any gift or legacy ..., and by three year' imprisonment." Prospective officer-holders were required to swear that they did not believe in the central Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation.

In 1779 Jefferson proposed "The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom", which was adopted in 1786. Its goal was complete separation of church and state; it declared the opinions of men to be beyond the jurisdiction of the civil magistrate. He asserted that the mind is not subject to coercion, that civil rights have no dependence on religious opinions, and that the opinions of men are not the concern of civil government. This became one of the American charters of freedom. This elevated declaration of the freedom of the mind was hailed in Europe as "an example of legislative wisdom and liberality never before known".[29]

From 1784 to 1786, Jefferson and James Madison worked together to oppose Patrick Henry's attempts to assess general taxes in Virginia to support churches. In 1786, the Virginia General Assembly passed Jefferson's Bill for Religious Freedom, which he had first submitted in 1779. It was one of only three accomplishments he put in his epitaph. The law read:

No man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burdened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.[30]

In his 1787 Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson stated:

Millions of innocent men, women and children, since the introduction of Christianity, have been burned, tortured, fined and imprisoned. What has been the effect of this coercion? To make one half the world fools and the other half hypocrites; to support roguery and error all over the earth. ... Our sister states of Pennsylvania and New York, however, have long subsisted without any establishment at all. The experiment was new and doubtful when they made it. It has answered beyond conception. They flourish infinitely. Religion is well supported; of various kinds, indeed, but all good enough; all sufficient to preserve peace and order: or if a sect arises, whose tenets would subvert morals, good sense has fair play, and reasons and laughs it out of doors, without suffering the state to be troubled with it. They do not hang more malefactors than we do. They are not more disturbed with religious dissensions. On the contrary, their harmony is unparalleled, and can be ascribed to nothing but their unbounded tolerance, because there is no other circumstance in which they differ from every nation on earth. They have made the happy discovery, that the way to silence religious disputes, is to take no notice of them. Let us too give this experiment fair play, and get rid, while we may, of those tyrannical laws.[31]

Accusations of being an infidel

During the 1800 presidential campaign, the New England Palladium wrote, "Should the infidel Jefferson be elected to the Presidency, the seal of death is that moment set on our holy religion, our churches will be prostrated, and some infamous 'prostitute', under the title of goddess of reason, will preside in the sanctuaries now devoted to the worship of the most High."[32] Federalists attacked Jefferson as a "howling atheist" and infidel, claiming that his attraction to the religious and political extremism of the French Revolution disqualified him from public office.[33][34] At that time, calling a person an infidel could mean a number of things, including that they did not believe in God. It was an accusation commonly levelled at Deists, although they believe in a deity. It was also directed at those thought to be harming the Christian faith in which they were raised.

While opposed to the institutions of organized religion, Jefferson consistently expressed his belief in God. For example, he invoked the notion of divine justice in 1782 in his opposition to slavery,[35] and invoked divine Providence in his second inaugural address.[36]

Jefferson did not shrink from questioning the existence of God. In a 1787 letter to his nephew and ward, Peter Carr, who was at school, Jefferson offered the following advice:

Fix Reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a God; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason than of blindfolded fear. ... Do not be frightened from this inquiry by any fear of its consequences. If it end in a belief that there is no God, you will find incitements to virtue in the comfort and pleasantness you feel in its exercise and in the love of others which it will procure for you. -- (Jefferson's Works, Vol. V., p. 322)[37]

Following the 1800 campaign, Jefferson became more reluctant to have his religious opinions discussed in public. He often added requests at the end of personal letters discussing religion that his correspondents be discreet regarding its contents.[38]

Separation of church and state

Jefferson sought what he called a "wall of separation between Church and State", which he believed was a principle expressed by the First Amendment. Jefferson's phrase has been cited several times by the Supreme Court in its interpretation of the Establishment Clause, including in cases such as Reynolds v. United States (1878), Everson v. Board of Education (1947), and McCollum v. Board of Education (1948).

In an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, he wrote:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof", thus building a wall of separation between church and State.[39]

In Jefferson's March 4, 1805, Drafts of Address of Second Inaugural he stated:

In matters of religion, I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the constitution independent of the powers of the general government. I have therefore undertaken, on no occasion, to prescribe the religious exercises suited to it; but have left them, as the constitution found them, under the direction and discipline of state or church authorities acknowledged by the several religious societies.[40]

Regarding the choice of some governments to regulate religion and thought, Jefferson stated:

The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.[41]

Deriving from this statement, Jefferson believed that the Government's relationship with the Church should be indifferent, religion being neither persecuted nor given any special status.

If anything pass in a religious meeting seditiously and contrary to the public peace, let it be punished in the same manner and no otherwise as it had happened in a fair or market[42]

Though he did so as Governor of Virginia, during his Presidency Jefferson refused to issue proclamations calling for days of prayer and thanksgiving. In a letter to Samuel Miller dated January 23, 1808 Jefferson stated:

But it is only proposed that I should recommend, not prescribe a day of fasting & prayer.[43]

However, in Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson supported "a perpetual mission among the Indian tribes" by the Christian Brafferton institution, at least in the interest of anthropology,[44] As president, he sanctioned financial support for a priest and church for the Kaskaskia Indians, who were at the time already Christianized and baptized. Edwin Gaustad wrote that this was a pragmatic political move aimed at stabilizing relations with the Indian tribes.[45]

Jefferson also publicly affirmed "acknowledging and adoring an overruling providence" by the nation in his First Inaugural Address[46] and in his Second Inaugural Address expressed his need of "the favor of that Being in whose hands we are, who led our fathers, as Israel of old", and thus asked the nation "to join in supplications" with him to God.[47]

Jefferson, Jesus, and the Bible

Jefferson's views on Jesus and the Bible were mixed, but were progressively far from what was and is largely considered orthodox in Christianity. Jefferson stated in a letter in 1819, "You say you are a Calvinist. I am not. I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know."[48] He also rejected the idea of the divinity of Christ, but as he writes to William Short on October 31, 1819, he was convinced that the fragmentary teachings of Jesus constituted the "outlines of a system of the most sublime morality which has ever fallen from the lips of man."[49]

On one hand Jefferson affirmed, "We all agree in the obligation of the moral precepts of Jesus, and nowhere will they be found delivered in greater purity than in his discourses",[50] and that he was "sincerely attached to His doctrines in preference to all others",[51] and that "the doctrines of Jesus are simple, and tend all to the happiness of man".[52] However, Jefferson considered much of the New Testament of the Bible to be false. In a letter to William Short in 1820, he expressed that his intent was to "place the character of Jesus in its true and high light, as no imposter himself", but that he was not with Jesus "in all his doctrines", Jefferson described many passages as "so much untruth, charlatanism and imposture".[53] In the same letter Jefferson states he is separating "the gold from the dross", and describes the "roguery of others of His disciples", [54] calling this group a "band of dupes and impostors", who wrote "palpable interpolations and falsifications", with Paul being the "first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus".[54]

Jefferson also denied the divine inspiration of the Book of Revelation, describing it to Alexander Smyth in 1825 as "merely the ravings of a maniac, no more worthy nor capable of explanation than the incoherences of our own nightly dreams".[55] From his study of the Bible, Jefferson concluded that Jesus never claimed to be God.[56]

In 1803 Jefferson composed a "Syllabus of an Estimate of the Merit of the Doctrines of Jesus" of the comparative merits of Christianity, after having read the pamphlet “Socrates and Jesus Compared” by the Unitarian minister, Dr. Joseph Priestley.[57] In this brief work Jefferson affirms Jesus' "moral doctrines, relating to kindred & friends, were more pure & perfect than those of the most correct of the philosophers, and greatly more so than those of the Jews", but asserts that "fragments only of what he did deliver have come to us mutilated, misstated, & often unintelligible", and that "the question of his being a member of the Godhead, or in direct communication with it, claimed for him by some of his followers, and denied by others is foreign to the present view, which is merely an estimate of the intrinsic merit of his doctrines".[58] He let only a few see it, including Benjamin Rush in 1803 and William Short in 1820. When Rush died in 1813, Jefferson asked the family to return the document to him.

Also while living in the White House, Jefferson began to piece together his own version of the Gospels, with the first draft being "The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth...Being an Abridgement of the New Testament for the Use of the Indians, Unembarrased [uncomplicated] with Matters of Fact or Faith beyond the Level of their Comprehensions". This was followed by a compilation titled, The LIFE AND MORALS OF JESUS OF NAZARETH: Extracted Textually from the Gospels Greek, Latin, French, and English, from which he omitted the virgin birth of Jesus, miracles attributed to Jesus, divinity, and the resurrection of Jesus – among many other teachings and events. He retained primarily Jesus' moral philosophy, of which he approved, and also included the Second Coming, a future judgment, Heaven, Hell, and a few other supernatural events.

This compilation was completed about 1820, but Jefferson did not make these works public, acknowledging "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth" existence only to a few friends.[59] This work was published after his death and became known as the Jefferson Bible.[9]

Anti-clericalism, anti-mysticism, and anti-Calvinism

While Jefferson did indeed include some Protestant clergymen as amongst his friends,[60] and while he did in fact donate monies in support of some clergy and some churches,[61] his attitude towards the "theology" of contemporary "Christianity" was one of extreme aversion. Towards the Roman Catholic church, Jefferson was uniformly adverse. Jefferson's residence in France just before the French Revolution left him deeply suspicious of Catholic priests and bishops as a force for reaction and ignorance. His later private letters indicate he was skeptical of too much interference by Catholic clergy in matters of civil government. He wrote in letters: "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government"[62] and "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."[63]

May it [the French Revolution] be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all), the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government.[64]

Observing inter-denominational intolerance in the United States, he extended his skepticism to Protestant clergy. In an 1820 letter to William Short, Jefferson wrote: "the serious enemies are the priests of the different religious sects, to whose spells on the human mind its improvement is ominous."[9]

In 1817 he wrote to John Adams:

The Christian priesthood, finding the doctrines of Christ levelled to every understanding and too plain to need explanation, saw, in the mysticisms of Plato, Materials with which they might build up an artificial system which might, from its indistinctness, admit everlasting controversy, give employment for their order, and introduce it to profit, power, and preeminence. The doctrines which flowed from the lips of Jesus himself are within the comprehension of a child; but thousands of volumes have not yet explained the Platonisms engrafted on them: and for this obvious reason that nonsense can never be explained.[65]

Jefferson intensely opposed Calvinism. He never ceased to denounce the "blasphemous absurdity of the five points of Calvin", writing three years before his death to John Adams:

His [Calvin's] religion was demonism. If ever man worshiped a false God, he did. The being described in his five points is ... a demon of malignant spirit. It would be more pardonable to believe in no God at all, than to blaspheme him by the atrocious attributes of Calvin.[66]

Aaron Bancroft observed, "It is hard to say, which surpassed the other in boiling hatred of Calvinism, Jefferson or John Adams."[67]

Priestley and Unitarianism

Jefferson expressed general agreement with Unitarianism, which, like Deism, rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. Jefferson never joined a Unitarian church, but he did attend Unitarian services while in Philadelphia. His friend Joseph Priestley was the minister. Jefferson corresponded on religious matters with numerous Unitarians, among them Jared Sparks (Unitarian minister, historian and president of Harvard), Thomas Cooper, Benjamin Waterhouse and John Adams. In an 1822 letter to Benjamin Waterhouse he wrote,

I rejoice that in this blessed country of free inquiry and belief, which has surrendered its conscience to neither kings or priests, the genuine doctrine of only one God is reviving, and I trust that there is not a young man now living in the United States who will not die a Unitarian.[68]

Jefferson named the teachings of both Joseph Priestley and Conyers Middleton (an English clergyman who questioned miracles and revelation, emphasizing Christianity's role as a mainstay of social order) as the basis for his own faith. He became friends with Priestley, who lived in Philadelphia. In a letter to John Adams dated August 22, 1813, Jefferson wrote,

You are right in supposing, in one of yours, that I had not read much of Priestley's Predestination, his no-soul system, or his controversy with Horsley. But I have read his Corruptions of Christianity, and Early Opinions of Jesus, over and over again; and I rest on them, and on Middleton's writings, especially his Letters from Rome, and To Waterland, as the basis of my own faith. These writings have never been answered, nor can be answered by quoting historical proofs, as they have done. For these facts, therefore, I cling to their learning, so much superior to my own.[69]

Jefferson continued to express his strong objections to the doctrines of the virgin birth, the divinity of Jesus, and the Trinity. In a letter to Adams (April 11, 1823), Jefferson wrote, "And the day will come, when the mystical generation of Jesus, by the Supreme Being as His Father, in the womb of a virgin, will be classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva, in the brain of Jupiter."[70]

In an 1821 letter he wrote:

No one sees with greater pleasure than myself the progress of reason in its advances towards rational Christianity. When we shall have done away the incomprehensible jargon of the Trinitarian arithmetic, that three are one, and one is three; when we shall have knocked down the artificial scaffolding, reared to mask from view the simple structure of Jesus; when, in short, we shall have unlearned everything which has been taught since His day, and got back to the pure and simple doctrines He inculcated, we shall then be truly and worthily His disciples; and my opinion is that if nothing had ever been added to what flowed purely from His lips, the whole world would at this day have been Christian. I know that the case you cite, of Dr. Drake, has been a common one. The religion-builders have so distorted and deformed the doctrines of Jesus, so muffled them in mysticisms, fancies and falsehoods, have caricatured them into forms so monstrous and inconceivable, as to shock reasonable thinkers, to revolt them against the whole, and drive them rashly to pronounce its Founder an impostor. Had there never been a commentator, there never would have been an infidel. ... I have little doubt that the whole of our country will soon be rallied to the unity of the Creator, and, I hope, to the pure doctrines of Jesus also.[71]

Jefferson once wrote to the minister of the First Parish Church (Unitarian) in Portland, Maine, asking for services for him and a small group of friends. The church responded that it did not have clergy to send to the South. In an 1825 letter to Waterhouse, Jefferson wrote:

I am anxious to see the doctrine of one god commenced in our state. But the population of my neighborhood is too slender, and is too much divided into other sects to maintain any one preacher well. I must therefore be contented to be an Unitarian by myself, altho I know there are many around me who would become so, if once they could hear the questions fairly stated.[10]

When followers of Richard Price and Priestley began debating over the existence of free-will and the soul (Priestley had taken the materialist position,[72]) Jefferson expressed reservations that Unitarians were finding it important to dispute doctrine with one another. In 1822 he held the Quakers up as an example for them to emulate.[73]

In Jefferson's time, Unitarianism was generally considered a branch of Christianity. Originally it questioned the doctrine of the Trinity and the pre-existence of Christ. During the period 1800-1850, Unitarianism began also to question the existence of miracles, the inspiration of Scripture, and the virgin birth, though not yet the resurrection of Jesus.[74]

Contemporary Unitarianism no longer implies belief in a deity; some Unitarians are theists and some are not. Modern Unitarians consider Jefferson both a kindred spirit and an important figure in their history. The Famous UUs website[75] says:

Like many others of his time (he died just one year after the founding of institutional Unitarianism in America), Jefferson was a Unitarian in theology, though not in church membership. He never joined a Unitarian congregation: there were none near his home in Virginia during his lifetime. He regularly attended Joseph Priestley's Pennsylvania church when he was nearby, and said that Priestley's theology was his own, and there is no doubt Priestley should be identified as Unitarian. Jefferson remained a member of the Episcopal congregation near his home, but removed himself from those available to become godparents, because he was not sufficiently in agreement with the Trinitarian theology. His work, the Jefferson Bible, was Unitarian in theology ...

General remarks

Biographer Merrill D. Peterson summarizes Jefferson's theology:

First, that the Christianity of the churches was unreasonable, therefore unbelievable, but that stripped of priestly mystery, ritual, and dogma, reinterpreted in the light of historical evidence and human experience, and substituting the Newtonian cosmology for the discredited Biblical one, Christianity could be conformed to reason. Second, morality required no divine sanction or inspiration, no appeal beyond reason and nature, perhaps not even the hope of heaven or the fear of hell; and so the whole edifice of Christian revelation came tumbling to the ground.[76]

In an 1820 letter to his close friend William Short, Jefferson stated, "it is not to be understood that I am with him [Jesus] in all his doctrines. I am a Materialist; he takes the side of Spiritualism; he preaches the efficacy of repentance toward forgiveness of sin; I require a counterpoise of good works to redeem it."[77] In 1824, four years later, Jefferson had changed on his view of the "materialism" of Jesus, clarifying then that "... the founder of our religion, was unquestionably a materialist as to man."[78][79]

Avery Dulles, a leading Catholic theologian, states that while at the College of William & Mary, "under the influence of several professors, he [Jefferson] converted to the deist philosophy".[20] Dulles concludes:

In summary, then, Jefferson was a deist because he believed in one God, in divine providence, in the divine moral law, and in rewards and punishments after death; but did not believe in supernatural revelation. He was a Christian deist because he saw Christianity as the highest expression of natural religion and Jesus as an incomparably great moral teacher. He was not an orthodox Christian because he rejected, among other things, the doctrines that Jesus was the promised Messiah and the incarnate Son of God. Jefferson's religion is fairly typical of the American form of deism in his day.

Dulles concurs with historian Stephen Webb, who states that Jefferson's frequent references to "Providence" indicate his Deism, as "most eighteenth-century deists believed in providence".[80]

The historian of religion Sydney E. Ahlstrom says "One religious movement which enjoyed a season of popularity, and great prestige during the era, in America as in France, was the cult of reason." Ahlstrom calls it "rational religion or deism".[81] Ahlstrom also uses the phrases "reasonable Christianity" and "Christian rationalists",[82] echoing Jefferson's own use of the phrase "rational Christianity".[83] Ahlstrom adds, "Thomas Jefferson was unquestionably the most significant of the American rationalists". He notes that, in content, his theology was similar to that of John Adams, Joel Barlow, Elihu Palmer, and Thomas Paine, "though Jefferson was more doctrinaire in his materialism".[84]

Historian Gregg L. Frazer argues that Jefferson's religious views fell between Christianity and Deism.[85] Frazer describes Jefferson as a theistic rationalist, a term from German theology whose first-found English usage is in the year 1856.[86] Frazer cites the following quote from Jefferson's 1785 Notes on the State of Virginia:

Can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever; that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events; that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.[87]

See also

- Bibliography of Thomas Jefferson

- Jesuism

- The Faiths of the Founding Fathers, a book on the subject

References

- ^ Charles Sanford, The Religious Life of Thomas Jefferson (Charlotte: UNC Press, 1987).

- ^ Michael Corbett and Julia Mitchell Corbett, Politics and religion in the United States (1999) p. 68

- ^ a b Thomas Jefferson: Deist or Christian? Debunking Dr James Kennedy Jefferson: "That there is a future state of rewards and punishments." By Lewis Loflin. Downloaded 15-04-03.

- ^ a b c Thomas Jefferson, Second Inaugural Address, Monday, March 4, 1805

- ^ Jefferson, Washington, 1907, p. 89

- ^ Thomas Jefferson and his Bible April, 1998, PBS Frontline, downloaded 15-04-03

- ^ Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address

- ^ Albert Ellery Bergh, ed. (1853). October 31, 1819 letter to William Short. Vol. XV. The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association. p. 219. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

As you say of yourself, I too am an Epicurian. I consider the genuine (not the imputed) doctrines of Epicurus as containing everything rational in moral philosophy which Greece and Rome have left us.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Letter to William Short". April 13, 1820.

- ^ a b Thomas Jefferson (January 8, 1825). "letter to Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse". The copy of this 1825 Thomas Jefferson letter to Waterhouse (1754-1846) is in an unknown hand.

- ^ Albert Ellery Bergh, ed. (1853). June 25, 1819 letter to Ezra Stiles Ely. Vol. XV. The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association. p. 202. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

You say you are a Calvinist. I am not. I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Works, Vol. iv., p. 301.

- ^ Ahlstrom p 366

- ^ Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (Margaret Bayard), The first forty years of Washington society, pp.13, 15

- ^ "Religion and the Federal Government: PART 2". Library of Congress Exhibition. (Religion and the Founding of the American Republic)

- ^ Henry S. Randall, The life of Thomas Jefferson, p. 555

- ^ a b Holmes, David ynn (2006). The Faiths of the Founding Fathers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-19-530092-5.

- ^ Holmes, David. "Monticello Speakers Forum: Thomas Jefferson and Religion". Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ Merrill D. Peterson, ed. Thomas Jefferson: Writings, p. 1236

- ^ a b Dulles, Avery (January 2005). "The Deist Minimum". First Things (149): 25+.

- ^ "Jefferson's Religious Beliefs". monticello.org. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^

Alexander Brodie, ed. (2003). The Cambridge Companion to the Scottish Enlightenment. Cambridge. p. 324.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book, trans. and ed. Douglas L. Wilson (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989), p. 159.

- ^ Clark, J. C. D. The language of liberty, 1660-1832. p. 347. (letter to J.P.P Derieux, July 25, 1788, Papers vol 13, p 418)

- ^ Breig, James (Spring 2009). "DEISM: One Nation Under A Clockwork God?". Colonial Williamsburg. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ Couvillon, Mark. "A Patrick Henry Essay: The Voice vs. the Pen" (PDF). National Forensic League. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson (1803). H.A. Washington (1861) (ed.). April 9, 1803 letter to Dr. Joseph Priestley. Washington: H.W. Derby.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: editors list (link)... In consequence of some conversation with Dr. Rush, in the year 1798-99, I had promised some day to write him a letter giving him my view of the Christian system. I have reflected often on it since, and even sketched the outlines in my own mind. I should first take a general view of the moral doctrines of the most remarkable of the ancient philosophers, of whose ethics we have sufficient information to make an estimate, say Pythagoras, Epicurus, Epictetus, Socrates, Cicero, Seneca, Antoninus. I should do justice to the branches of morality they have treated well; but point out the importance of those in which they are deficient. I should then take a view of the deism and ethics of the Jews, and show in what a degraded state they were, and the necessity they presented of a reformation. I should proceed to a view of the life, character, and doctrines of Jesus, who sensible of incorrectness of their ideas of the Deity, and of morality, endeavored to bring them to the principles of a pure deism, and juster notions of the attributes of God, to reform their moral doctrines to the standard of reason, justice and philanthropy, and to inculcate the belief of a future state. This view would purposely omit the question of his divinity, and even his inspiration. To do him justice, it would be necessary to remark the disadvantages his doctrines had to encounter, not having been committed to writing by himself, but by the most unlettered of men, by memory, long after they had heard them from him; when much was forgotten, much misunderstood, and presented in every paradoxical shape. Yet such are the fragments remaining as to show a master workman, and that his system of morality was the most benevolent and sublime probably that has been ever taught, and consequently more perfect than those of any of the ancient philosophers. His character and doctrines have received still greater injury from those who pretend to be his special disciples, and who have disfigured and sophisticated his actions and precepts, from views of personal interest, so as to induce the unthinking part of mankind to throw off the whole system in disgust, and to pass sentence as an impostor on the most innocent, the most benevolent, the most eloquent and sublime character that ever has been exhibited to man...

- ^

Albert Ellery Bergh, ed. (1853). May 5, 1817 letter to John Adams. Vol. 15. The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, & A.A. Lipscomb. pp. 108–109. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

I had believed that [Connecticut was] the last retreat of monkish darkness, bigotry, and abhorrence of those advances of the mind which had carried the other States a century ahead of them. ... I join you, therefore, in sincere congratulations that this den of the priesthood is at length broken up, and that a Protestant Popedom is no longer to disgrace the American history and character. If by religion we are to understand [i.e., to mean] sectarian dogmas, in which no two of them agree, then your exclamation on that hypothesis is just, 'that this would be the best of all possible worlds, if there were no religion in it.' But if the moral precepts, innate in man, and made a part of his physical constitution, as necessary for a social being, if the sublime doctrines of philanthropism and deism taught us by Jesus of Nazareth, in which all agree, constitute true religion, then, without it, this would be, as you again say, 'something not fit to be named even, indeed, a hell'.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Price, Richard (July 26, 1786). The Correspondence of Richard Price. Letter to Sylvanus Urban. p. vol 2, p 45. ISBN 978-0-8223-1327-4.

- ^ Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: Writings (1984), p. 347

- ^ "Notes on the State of Virginia".

- ^ "New England Palladium, 1800 remarks about Jefferson". 1800. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- ^ Isaac Kramnick, and Robert Laurence Moore (1997). The Godless Constitution: The Case against Religious Correctness. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393315240. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ^ Ferling, John. Adams vs. Jefferson, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 154. ISBN 0-19-516771-6

- ^

"Notes on the State of Virginia, Q.XVIII". 1782.

This is so true, that of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed are ever seen to labour. And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice can not sleep forever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference!"

- ^ "Jefferson's Second Inaugural Address", Bartleby Quotes

- ^ "1787 letter to nephew Peter Carr". 1787.

- ^ Albert Ellery Bergh, ed. (1853). April 21, 1803 letter to Doctor Benjamin Rush. Vol. X. The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association. p. 379. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

... To the corruptions of Christianity I am, indeed, opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other.... And in confiding it [an enclosed syllabus] to you, I know it will not be exposed to the malignant perversions of those who make every word from me a text for new misrepresentations and calumnies. I am moreover averse to the communication of my religious tenets to the public; because it would countenance the presumption of those who have endeavored to draw them before that tribunal, and to seduce public opinion to erect itself into that inquisition over the rights of conscience, which the laws have so justly proscribed....

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Wikisource:Letter to the Danbury Baptists - January 1, 1802, January 1, 1802

- ^ "Draft of 2nd Inaugural". Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ Notes on the State of Virginia

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (1900). John P. Foley (ed.). The Jeffersonian Cyclopedia: a Comprehensive Collection of the Views of Thomas Jefferson. New York City: Funk and Wagnalls. p. 140.

- ^ [1]

- ^ University of Virginia Library, Jefferson's Notes on Virginia, p. 210

- ^ Edwin S. Gaustad, Sworn of the Altar of God: A Religious Biography of Thomas Jefferson, p. 101.

- ^ ,Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address

- ^ Thomas Jefferson, Second Inaugural Address

- ^ Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Ezra Stiles Ely, June 25, 1819, Encyclopedia Virginia

- ^ https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/jeffersons-religious-beliefs

- ^ Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Alberty Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XII, p. 315, to James Fishback, September 27, 1809

- ^ Thomas Jefferson, Memoirs, correspondence and private papers of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 3; Letter to Benjamin rush, April 21, 1803

- ^ Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. XII, p. 383

- ^ Thomas Jefferson & Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1829). Memoirs, Correspondence, and Private Papers of Thomas Jefferson : Late President of the United States. London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. OCLC 19942206. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ a b Jefferson, Thomas (1854). H. A. WASHINGTON (ed.). The Writings of Thomas Jefferson: Being His Autobiography, Correspondence. WASHINGTON, D. C: TAYLOR & MATJRY. p. 156. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (1854). H. A. WASHINGTON (ed.). The Writings of Thomas Jefferson: Being His Autobiography, Correspondence. WASHINGTON, D. C: TAYLOR & MATJRY. p. 395. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Edward J. Larson, A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America's First Presidential Campaign (Simon and Schuster, 2007), p. 171.

- ^ Jared Farley, Jefferson's "Syllabus", "Philosophy" and "Life & Morals"

- ^ page 1 & page 2

- ^ Smithsonian magazine, Secretary Clough on Jefferson's Bible, October 2011

- ^ The Thomas Jefferson Hour: Clay Jenkinson book review, June 3, 2012 Excerpt: "Jefferson had many friends who were pastors, ministers, theologians, preachers, and priests".

- ^ Jefferson's Religious Beliefs Monticello.org Discussion of Jefferson's church donations. Downloaded 15-04-03.

- ^ Letter to Alexander von Humboldt regarding religion in Mexico, December 6, 1813

- ^ Letter to Horatio G. Spafford, March 17, 1814

- ^ Letter to Roger C. Weightman June 24, 1826

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (1829). Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies: From the Papers of Thomas Jefferson. H. Colburn and R. Bentley. p. 242. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ (Works, Vol. iv., p. 363.

- ^ as quoted by Bennett, De Robigne Mortimer (1876). The World's Sages, Thinkers and Reformers: Being Biographical Sketches of Leading Philosophers, Teachers, Skeptics, Innovators, Founders of New Schools of Thought, Eminent Scientists, Etc. New York: The Truth Seeker Company. p. 567.

- ^ "1822 Letter to Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse". June 26, 1822. (meaning, at least, that they would not be "a Trinitarian")

- ^ "letter in reply to John Adams". Monticello. August 22, 1813. Retrieved 2011-02-22. Note: Conyers Middleton's name is often omitted when this quote is cited; thereby leading to the inference that Jefferson is relying solely upon Priestley. Middleton defended Deist Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation against attacks by Daniel Waterland.

- ^ Letter to John Adams. Monticello. April 1823. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- ^ Letter to Timothy Pickering, Esq. Monticello. February 27, 1821. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Kingston, Elizabeth (2008). "Joseph Priestley". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ "Letter To Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse". Monticello. June 26, 1822.

I rejoice that in this blessed country of free inquiry and belief, which has surrendered its creed and conscience to neither kings nor priests, the genuine doctrine of one only God is reviving, and I trust that there is not a young man now living in the United States who will not die an Unitarian. But much I fear, that when this great truth shall be re-established, its votaries will fall into the fatal error of fabricating formulas of creed and confessions of faith, the engines which so soon destroyed the religion of Jesus.... How much wiser are the Quakers, who, agreeing in the fundamental doctrines of the gospel, schismatize about no mysteries, and, keeping within the pale of common sense, suffer no speculative differences of opinion, any more than of feature, to impair the love of their brethren.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 299 (help) - ^ R. K. Webb, "Miracles in English Unitarian Thought", in Mark S. Micale, Robert L. Dietle, Peter Gay, editors, Enlightenment, Passion, Modernity: Historical Essays in European Thought and Culture, 2000

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson". Unitarian Universalist Association. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ Peterson, Merrill D. (1975). Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation. pp. 50–51.

- ^ The character of Thomas Jefferson: as exhibited in his own writings By Theodore Dwight, Pg. 363

- ^ The Battle for the American Mind: A Brief History of a Nation's Thought By Carl J. Richard, Pg. 98

- ^ Letter from Jefferson to Augustus Elias Brevoort Woodward, 24 March 1824 Downloaded 15-04-22, National Archives

- ^ Stephen H. Webb, American providence: a nation with a mission (2004) p. 35

- ^ Sydney E. Alstrom, A Religious History of the American People (1972), p. 366

- ^ Sydney E. Alstrom, A Religious History of the American People (1972), pp. 357, 366

- ^ Jefferson to Timothy Pickering, Feb. 27 1821

- ^ Sydney E. Alstrom, A Religious History of the American People (1972), pp. 367–68

- ^ Gregg L. Frazer, The Religious Beliefs of America's Founders: Reason, Revelation, Revolution (University Press of Kansas, 2012), p. 11

- ^ "Googlebooks search for "theistic rationalism"".

- ^ Frazer, The Religious Beliefs of America's Founders: Reason, Revelation, Revolution p. 128, quoting Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia, 1800 ed., p. 164.

Bibliography

- Gaustad, Edwin S. Sworn on the Altar of God: A Religious Biography of Thomas Jefferson (2001) Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 0-8028-0156-0

- Healey, Robert M. Jefferson on religion in public education (Yale University Press, 1962)

- Koch, Adrienne. The Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson (Columbia University Press, 1943)

- Neem, Johann N. "Beyond the Wall: Reinterpreting Jefferson's Danbury Address." Journal of the Early Republic 27.1 (2007): 139-154.

- Novak, Michael. The founders on God and government (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2004)

- Perry, Barbara A. "Jefferson's legacy to the Supreme Court: Freedom of religion." Journal of Supreme Court History 31.2 (2006): 181-198.

- Ragosta, John A. "The Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom." in y Francis D. Cogliano, ed., A Companion to Thomas Jefferson (2011): 75-90.

- Sanford, Charles B. The Religious Life of Thomas Jefferson (1987) University of Virginia Press, ISBN 0-8139-1131-1

- Sheridan, Eugene R. Jefferson and Religion, preface by Martin Marty, (2001) University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 1-882886-08-9

- Edited by Jackson, Henry E., President, College for Social Engineers, Washington, D. C. "The Thomas Jefferson Bible" (1923) Copyright Boni and Liveright, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Arranged by Thomas Jefferson. Translated by R. F. Weymouth. Located in the National Museum, Washington, D. C.