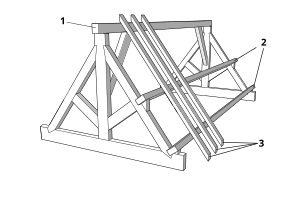

Timber roof truss

Key:1: ridge beam, 2: purlins, 3: common rafters. This is an example of a "double roof" with principal rafters and common rafters.

A timber roof truss is a structural framework of timbers designed to bridge the space above a room and to provide support for a roof. Trusses usually occur at regular intervals, linked by longitudinal timbers such as purlins. The space between each truss is known as a bay.[1]

Rafters have a tendency to flatten under gravity, thrusting outwards on the walls. For larger spans and thinner walls, this can topple the walls. Pairs of opposing rafters were thus initially tied together by a horizontal tie beam, to form coupled rafters. But such roofs were structurally weak, and lacking any longitudinal support, they were prone to racking, a collapse resulting from horizontal movement. Timber roof trusses were a later, medieval development.[2] A roof truss is cross-braced into a stable, rigid unit. Ideally, it balances all of the lateral forces against one another, and thrusts only directly downwards on the supporting walls. In practice, lateral forces may develop; for instance, due to wind, excessive flexibility of the truss, or constructions that do not accommodate small lateral movements of the ends of the truss.

History

[edit]

The top members of a truss are known generically as the top chord, bottom members as the bottom chord, and the interior members as webs. In historic carpentry the top chords are often called rafters, and the bottom chord is often referred to as a tie beam. There are two main types of timber roof trusses: closed, in which the bottom chord is horizontal and at the foot of the truss, and open, in which the bottom chords are raised to provide more open space, also known as raised bottom chord trusses.[3]

Closed trusses

[edit]Closed/open distinction is used in two ways to describe truss roofs.

Closed truss:

- A truss with a tie beam; or

- Roof framing with a ceiling so the framing is not visible.

Open truss:

- A truss with an interrupted tie beam or scissor truss which allow a vaulted ceiling area; or

- Roof framing open to view, not hidden by a ceiling.[4]

King post truss

[edit]

Key: 1: king post, 2: tie beam, 3: principal rafters, 4: struts.

A king post truss has two principal rafters, a tie beam, and a central vertical king post.[5] The simplest of trusses, it is commonly used in conjunction with two angled struts.

The king post is normally under tension, and requires quite sophisticated joints with the tie beam and principal rafters. In a variation known as a king bolt (rod) truss the king post is replaced by a metal bolt (rod), usually of wrought iron.

Queen post truss

[edit]

Key: 1: queen posts, 2: tie beam, 3: straining beam, 4: principal rafters.

A queen post truss has two principal rafters and two vertical queen posts.[5] The queen post truss extends the span, and combined with spliced joints in the longer members extends the useful span for trusses of these types. As with a king post, the queen posts may be replaced with iron rods and thus called a queen rod truss. This truss is often known as a palladiana (Palladian truss) in Italy, as it was frequently used by the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio.[6][a] Sometimes a Palladian truss is defined as a compound truss with a queen post and king post truss in the same assembly.[7]

The queen post truss and the king post truss may be combined, by using the straining beam of the queen post truss as the tie beam for a king post truss above.[8] Such combinations are known as compound trusses.

Liegender Stuhl

[edit]

Liegender Stuhl is a truss of German origin; the German name is used in America. This truss is found in some 18th- and 19th-century buildings where Germans settled in the U.S. The literal translation is "lying chair", lying meaning the top chords are angled or leaning (and chair in the sense of a support, in this case a post or truss).[9] Carpenters in the Netherlands also used this truss where it is spelled liggende stoel.[10]

The opposite being a "Stehender Stuhl", which is the common roof truss type where simple vertical posts replace the more elaborate support structure in the image (highlighted in blue).

Open trusses

[edit]Arch-braced truss

[edit]

Key: 1: principal rafters, 2: collar beam, 3: arch braces.

Lacking a tie beam,[11] the arch-braced (arched brace)[12] truss gives a more open look to the interior of the roof. The principal rafters are linked by a collar beam supported by a pair of arch braces, which stiffen the structure and help to transmit the weight of the roof down through the principal rafters to the supporting wall. A double arch braced truss[12] has a second pair of arched braces lower down, from the rafter to a block or inner sill: This form is called a wagon, cradle, barrel or tunnel roof because of this cylindrical appearance.[13]

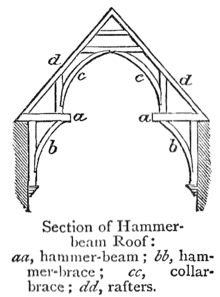

Hammerbeam truss

[edit]

The hammerbeam roof was the culmination of the development of the arch-braced truss, allowing greater spaces to be spanned. The hammerbeam roof of Westminster Hall in London, designed by Hugh Herland and installed between 1395 and 1399, was the largest timber-roofed space in medieval Europe, spanning a distance of just over 20 metres (66 ft).[14] It is considered to be the best example of a hammer-beam truss in England.[15]

Hammer beam trusses can have a single hammerbeam or multiple hammerbeams. A false hammerbeam roof (truss) has two definitions: 1) There is no hammer post on the hammer beam[16][17] as sometimes found in a type of arch brace truss[18] or; 2)The hammer beam joins into the hammer post instead of the hammer post landing on the hammer beam.[19]

Scissor truss

[edit]

The scissor truss gets its name from being shaped like a pair of shears (scissors). Two defining features of a scissor truss are: 1) the joint where the bottom chords pass (the hinge of a pair of scissors) must be firmly connected and 2) the rafter (top chord) feet must land on the bottom chords. If the bottom chords join to the under-side of the top chords the assembly is said to be "scissor braced"[20] rather than a scissor truss.

Bracing

[edit]It has been proven that permanent bracing designs can improve the lateral stability of roof trusses, specifically with j chords. Continuous lateral braces can prevent negative effects of lateral forces by being diagonally set in to brace the chord. However, there are variable effects of permanent braces on the truss web, given that the length of the chord would determine the number of brace locations.[21]

Pre-fabricated wood trusses

[edit]Pre-fabricated wood trusses offer advantages in building construction through machine-made accuracy and tend to use less timber.[22] However, this does not take into account site-specific design alterations that require customized truss design.

Historic wood trusses

[edit]The challenges of maintaining wood trusses are not limited to newer building projects. Visual grading can be used to conduct condition assessments for historic trusses. This along with load carrying tests, can be used to determine the best possible solutions to repairing older truss systems. Metal plates and correct, period material can be used to repair, although 100% recovery of the material may be hard if the wood truss has deteriorated. MPC (Metal Plate Connected) wood trusses are typically made from dressed wood (lumber), rather than timber (round-wood poles).[23]

Connections in wooden trusses

[edit]The earliest wooden truss connections consisted of mortise-and-tenon joints and were most likely crafted at the construction site with the posts. Since most early trusses were made from unseasoned posts, the subsequent shrinkage would create cracking at the mortise-and-tenon joints. Additionally, the mortise-and-tenon joints in older trusses were located at the weakest point in the post, accelerating failure. Much of the early truss connection designs anticipated structural behaviour under loads. This is why holes were drilled slightly off-centre, allowing the peg to naturally pull the posts together with gravity.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

Citations

- ^ Curl, James Stevens (2006), "truss", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (online ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9, retrieved 1 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ Steane (1984), p. 196

- ^ Lewandoski, Jan, Jack Sobon, and Kenneth Rower. Historic American roof trusses. Becket, MA: Timber Framers Guild, 2006. 48. ISBN 0970664346

- ^ Domestic Buildings Research Group (Surrey, England), http://www.dbrg.org.uk/GLOSSARY/Open%20truss.html

- ^ a b Glossary of Australian Building Terms – Third Edition.(NCRB)

- ^ a b Valeriani, Simona (August 2006), "The Roofs of Wren and Jones: A Seventeenth-Century Migration of Technical Knowledge from Italy to England". Working Papers on the Nature of Evidence: How Well Do 'Facts' Travel?" (PDF), Department of Economic History, London School of Economics, retrieved 22 December 2012

- ^ Proceedings of the Third Annual Congress on Construction History, May 2009. Figure 1. based on Sachero, C., 1864: Sulla stabilità delle armature dei tetti. Giornale del Genio Militare 2. 250. http://www.bma.arch.unige.it/PDF/CONSTRUCTION_HISTORY_2009/VOL3/TURRI-Zamperin_Cappelletti_1_paper-revised_layouted.pdf accessed 12/24/2012

- ^ Yeomans (2003), p. 42

- ^ Anderegg, Jean. Holzbaukunst: Fachwerk, Dachgerüst, Zimmermannswerkzeug : systematisches Fachwörterbuch = Architecture en bois : construction en pan de bois, charpente de toit, outils du charpentier : dictionnaire spécialisé et systématique = Architecture in wood : timber-frame construction, roof frame, carpenter's tools : specialized and systematic dictionary. Munich: K.G. Saur, 1997. : 65. ISBN 3598104618

- ^ Herman Janse, Houten kappen in Nederland 1000-1940. Delftse Universitaire Pers, Delft / Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg, Zeist 1989.

- ^ Harris (2003), pp. 75–77

- ^ a b Chappell, Steve. A timber framer's workshop: joinery, design & construction of traditional timber frames. Brownfield, Me.: Fox Maple Press, 1998. 115. Print.

- ^ Whewell, William, and F. de. Lassaulx. Architectural notes on German churches; with notes written during an architectural tour in Picardy and Normandy.. The 3d ed. Cambridge: J. and J.J. Deighton; [etc.], 1842. 44. Print.

- ^ Steane (1984), pp. 196–97

- ^ Webber, Frederick G.. Carpentry & Joinery. Methuen and Co., London: 1898. 152.

- ^ Davies, Nikolas, and Erkki Jokiniemi. Dictionary of architecture and building construction. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Architectural Press, 2008. 144.

- ^ Alcock, N. W.. Recording timber-framed buildings: an illustrated glossary. London: Council for British Archaeology, 1989.

- ^ Sharpe, Geoffrey R.. Historic English churches a guide to their construction, design and features. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011. 111. fig. 61.

- ^ Wood, Margaret. The English Mediaeval House. London: Ferndale Editions, 1980, 1965. 319.

- ^ Lewandoski, Jan, Jack Sobon, and Kenneth Rower. Historic American roof trusses. Becket, MA: Timber Framers Guild, 2006. 7. ISBN 0970664346

- ^ Permanent bracing design for MPC wood roof truss webs and chords, Forest Products Journal, 51(7), 73-81

- ^ "The benefits of pre-fabricated timber roof trusses." Civil Engineering (10212000) 24, no. 7: 47-48. Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 8, 2017)

- ^ Non-destructive assessment, full-scale load-carrying tests and local interventions on two historic timber collar roof trusses. Engineering structures, 140.

- ^ "Early Wooden Truss Connections vs. Wood Shrinkage: From Mortise-and-Tenon Joints to Bolted Connections" APT Bulletin, Vol. 27, No. 1/2, A Tribute to Lee H. Nelson (1996), pp. 11-23.

Bibliography

- Harris, Richard (2003), Discovering Timber-framed Buildings, Shire Publications, ISBN 978-0-7478-0215-0

- Steane, John (1984), Archaeology of Mediaeval England and Wales, Croom Helm, ISBN 978-0-7099-2385-5

- Yeomans, David T. (2003), The Repair of Historic Timber Structures, Thomas Telford, ISBN 978-0-7277-3213-2

- Hoffsummer, Patrick, ed. (2009), Roof Frames from the 11th to the 19th Century. Typology and Development in Northern France and in Belgiums, Brepols, ISBN 978-2-503-52987-5