Solar sail

Solar sails (also called light sails or photon sails) are a form of spacecraft propulsion using the radiation pressure (also called solar pressure) from stars to push large ultra-thin mirrors to high speeds. Light sails could also be driven by energy beams to extend their range of operations, which is strictly beam sailing rather than solar sailing.

Solar sail craft offer the possibility of low-cost operations combined with long operating lifetimes. Since they have few moving parts and use no propellant, they can potentially be used numerous times for delivery of payloads.

Solar sails use a phenomenon that has a proven, measured effect on spacecraft. Solar pressure affects all spacecraft, whether in interplanetary space or in orbit around a planet or small body. A typical spacecraft going to Mars, for example, will be displaced by thousands of kilometres by solar pressure, so the effects must be accounted for in trajectory planning, which has been done since the time of the earliest interplanetary spacecraft of the 1960s. Solar pressure also affects the attitude of a craft, a factor that must be included in spacecraft design.[1]

The total force exerted on an 800 by 800 meter solar sail, for example, is about 5 newtons (1.1 lbf) at Earth's distance from the Sun,[2] making it a low-thrust propulsion system, similar to spacecraft propelled by electric engines.

History of concept

Johannes Kepler observed that comet tails point away from the Sun and suggested that the Sun caused the effect. In a letter to Galileo in 1610, he wrote, "Provide ships or sails adapted to the heavenly breezes, and there will be some who will brave even that void." He might have had the comet tail phenomenon in mind when he wrote those words, although his publications on comet tails came several years later.[3]

James Clerk Maxwell, in 1861–64, published his theory of electromagnetic fields and radiation, which shows that light has momentum and thus can exert pressure on objects. Maxwell's equations provide the theoretical foundation for sailing with light pressure. So by 1864, the physics community and beyond knew sunlight carried momentum that would exert a pressure on objects.

Jules Verne, in From the Earth to the Moon,[4] published in 1865, wrote "there will some day appear velocities far greater than these [of the planets and the projectile], of which light or electricity will probably be the mechanical agent ... we shall one day travel to the moon, the planets, and the stars."[5] This is possibly the first published recognition that light could move ships through space.

Pyotr Lebedev was first to successfully demonstrate light pressure, which he did in 1899 with a torsional balance;[6] Ernest Nichols and Gordon Hull conducted a similar independent experiment in 1901 using a Nichols radiometer.[7]

Albert Einstein provided a different formalism by his recognizing the equivalence of mass and energy. He simply wrote p = E/c as the relationship between the momentum, the energy, and the speed of light.

Svante Arrhenius predicted in 1908 the possibility of solar radiation pressure distributing life spores across interstellar distances, providing one means to explain the concept of panspermia. He apparently was the first scientist to state that light could move objects between stars.[8]

Friedrich Zander (Tsander) published a technical paper in 1925 that included technical analysis of solar sailing. Zander wrote of "using tremendous mirrors of very thin sheets" and "using the pressure of sunlight to attain cosmic velocities".[9]

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky first proposed using the pressure of sunlight to propel spacecraft through space and suggested, "using tremendous mirrors of very thin sheets to utilize the pressure of sunlight to attain cosmic velocities".[10]

JBS Haldane speculated in 1927 about the invention of tubular spaceships that would take humanity to space and how "wings of metallic foil of a square kilometre or more in area are spread out to catch the Sun's radiation pressure".[11]

J.D. Bernal wrote in 1929, "A form of space sailing might be developed which used the repulsive effect of the Sun's rays instead of wind. A space vessel spreading its large, metallic wings, acres in extent, to the full, might be blown to the limit of Neptune's orbit. Then, to increase its speed, it would tack, close-hauled, down the gravitational field, spreading full sail again as it rushed past the Sun."[12]

The first formal technology and design effort for a solar sail began in 1976 at Jet Propulsion Laboratory for a proposed mission to rendezvous with Halley's Comet.[2]

Physical principles

Solar radiation pressure

Solar radiation exerts a pressure on the sail due to reflection and a small fraction that is absorbed.

The momentum of a photon or an entire flux is given by Einstein's relation:[13][14]

- p = E/c

where p is the momentum, E is the energy (of the photon or flux), and c is the speed of light. Solar radiation pressure can be related to the irradiance (solar constant) value of 1361 W/m2 at 1 AU (Earth-Sun distance), as revised in 2011:[15]

- perfect absorbance: F = 4.54 μN per square metre (4.54 μPa) in the direction of the incident beam

- perfect reflectance: F = 9.08 μN per square metre (9.08 μPa) in the direction normal to surface

An ideal sail is flat and has 100% specular reflection. An actual sail will have an overall efficiency of about 90%, about 8.17 μN/m2,[14] due to curvature (billow), wrinkles, absorbance, re-radiation from front and back, non-specular effects, and other factors.

The force on a sail and the actual acceleration of the craft vary by the inverse square of distance from the Sun (unless extremely close to the Sun[16]), and by the square of the cosine of the angle between the sail force vector and the radial from the Sun, so

- F = F0 cos2 θ / R2 (ideal sail)

where R is distance from the Sun in AU. An actual square sail can be modeled as:

- F = F0 (0.349 + 0.662 cos 2θ − 0.011 cos 4θ) / R2

Note that the force and acceleration approach zero generally around θ = 60° rather than 90° as one might expect with an ideal sail.[17]

If some of the energy is absorbed, the absorbed energy will heat the sail, which re-radiates that energy from the front and rear surfaces, depending on the emissivity.

Solar wind, the flux of charged particles blown out from the Sun, exerts a nominal dynamic pressure of about 3 to 4 nPa, three orders of magnitude less than solar radiation pressure on a reflective sail.[18]

Sail parameters

Sail loading (areal density) is an important parameter, which is the total mass divided by the sail area, expressed in g/m2. It is represented by the Greek letter σ.

A sail craft has a characteristic acceleration, ac, which it would experience at 1 AU when facing the Sun. Using the value from above of 9.08 μN per square metre of radiation pressure at 1 AU, ac is related to areal density by:

- ac = 9.08(efficiency) / σ mm/s2

Assuming 90% efficiency, ac = 8.17 / σ mm/s2

The lightness number, λ, is the dimensionless ratio of maximum vehicle acceleration divided by the Sun's local gravity. Using the values at 1 AU:

- λ = ac / 5.93

The lightness number is also independent of distance from the Sun because both gravity and light pressure fall off as the inverse square of the distance from the Sun. Therefore, this number defines the types of orbit maneuvers that are possible for a given vessel.

The table presents some example values. Payloads are not included. The first two are from the detailed design effort at JPL in the 1970s. The third, the lattice sailer, might represent about the best possible performance level.[2] The dimensions for square and lattice sails are edges. The dimension for heliogyro is blade tip to blade tip.

| Type | σ (g/m2) | ac (mm/s2) | λ | Size (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square sail | 5.27 | 1.56 | 0.26 | 0.820 |

| Heliogyro | 6.39 | 1.29 | 0.22 | 15 |

| Lattice sailer | 0.07 | 117 | 20 | 0.840 |

Attitude control

An active attitude control system (ACS) is essential for a sail craft to achieve and maintain a desired orientation. The required sail orientation changes slowly (often less than 1 degree per day) in interplanetary space, but much more rapidly in a planetary orbit. The ACS must be capable of meeting these orientation requirements. Attitude control is achieved by a relative shift between the craft's center of pressure and its center of mass. This can be achieved with control vanes, movement of individual sails, movement of a control mass, or altering reflectivity.

Holding a constant attitude requires that the ACS maintain a net torque of zero on the craft. The total force and torque on a sail, or set of sails, is not constant along a trajectory. The force changes with solar distance and sail angle, which changes the billow in the sail and deflects some elements of the supporting structure, resulting in changes in the sail force and torque.

Sail temperature also changes with solar distance and sail angle, which changes sail dimensions. The radiant heat from the sail changes the temperature of the supporting structure. Both factors affect total force and torque.

To hold the desired attitude the ACS must compensate for all of these changes.[19]

Constraints

In Earth orbit, solar pressure and drag pressure are typically equal at an altitude of about 800 km, which means that a sail craft would have to operate above that altitude. Sail craft must operate in orbits where their turn rates are compatible with the orbits, which is generally a concern only for spinning disk configurations.

Sail operating temperatures are a function of solar distance, sail angle, reflectivity, and front and back emissivities. A sail can be used only where its temperature is kept within its material limits. Generally, a sail can be used rather close to the Sun, around 0.25 AU, or even closer if carefully designed for those conditions.[2]

Applications

Potential applications for sail craft range throughout the Solar System, from near the Sun to the comet clouds beyond Neptune. The craft can make outbound voyages to deliver loads or to take up station keeping at the destination. They can be used to haul cargo and possibly also used for human travel.[2]

Inner planets

For trips within the inner Solar System, they can deliver loads and then return to Earth for subsequent voyages, operating as an interplanetary shuttle. For Mars in particular, the craft could provide economical means of routinely supplying operations on the planet according to Jerome Wright, "The cost of launching the necessary conventional propellants from Earth are enormous for manned missions. Use of sailing ships could potentially save more than 10 billion dollars in mission costs."[2]

Solar sail craft can approach the Sun to deliver observation payloads or to take up station keeping orbits. They can operate at 0.25 AU or closer. They can reach high orbital inclinations, including polar.

Solar sails can travel to and from all of the inner planets. Trips to Mercury and Venus are for rendezvous and orbit entry for the payload. Trips to Mars could be either for rendezvous or swing-by with release of the payload for aerodynamic braking.[2]

Outer planets

Minimum transfer times to the outer planets benefit from using an indirect transfer (solar swing-by). However, this method results in high arrival speeds. Slower transfers have lower arrival speeds.

The minimum transfer time to Jupiter for ac of 1 mm/s2 with no departure velocity relative to Earth is 2 years when using an indirect transfer (solar swing-by). The arrival speed (V∞) is close to 17 km/s. For Saturn, the minimum trip time is 3.3 years, with an arrival speed of nearly 19 km/s.[2]

Minimum times to the outer planets (ac = 1 mm/s2) Jupiter Saturn Uranus Neptune Time, yr 2.0 3.3 5.8 8.5 Speed, km/s 17 19 20 20

Oort Cloud / Sun's inner gravity focus

The Sun's inner gravity focus is a point, at about 550 AU in the inner Oort cloud, at which light from distant objects is focused by gravity as it passes the Sun. This is thus an ideal distance from which to observe the region of deep space on the other side of the Sun.[20]

A small team had initially proposed a beryllium inflated sail that would go down to 0.05 AU from the Sun in order to get an acceleration peaking at 36.4 m/s2, reaching a speed of 0.00264c (about 950 km/s) in less than a day. Such proximity to the Sun could prove to be impractical in the near term due to the structural degradation of beryllium at high temperatures, diffusion of Hydrogen at high temperatures as well as an electrostatic gradient, generated by the ionization of beryllium due to the solar wind, posing a burst risk; thus a revised perihelion of 0.1 AU was proposed to reduce the aforementioned temperature and solar flux exposure.[21] Such a sail would take "Two and a half years to reach the heliopause, six and a half years to get to the Sun’s inner gravitational focus. with arrival at the inner Oort Cloud in no more than thirty years."[20] "Such a mission could perform useful astrophysical observations en route, explore gravitational focusing techniques, and image Oort Cloud objects while exploring particles and fields in that region that are of galactic rather than solar origin."

Satellites

Robert L. Forward pointed out that a solar sail could be used to modify the orbit of a satellite around the Earth. In the limit, a sail could be used to "hover" a satellite above one pole of the Earth. Spacecraft fitted with solar sails could also be placed in close orbits about the Sun that are stationary with respect to either the Sun or the Earth, a type of satellite named by Forward a statite. This is possible because the propulsion provided by the sail offsets the gravitational potential of the Sun. Such an orbit could be useful for studying the properties of the Sun over long durations.[citation needed] Likewise a solar sail-equipped spacecraft could also remain on station nearly above the polar terminator of a planet such as the Earth by tilting the sail at the appropriate angle needed to just counteract the planet's gravity.[citation needed]

In his book The Case for Mars, Robert Zubrin points out that the reflected sunlight from a large statite placed near the polar terminator of the planet Mars could be focused on one of the Martian polar ice caps to significantly warm the planet's atmosphere. Such a statite could be made from asteroid material.

Trajectory corrections

The MESSENGER probe orbiting Mercury used light pressure on its solar panels to perform fine trajectory corrections on the way to Mercury.[22] By changing the angle of the solar panels relative to the Sun, the amount of solar radiation pressure was varied to adjust the spacecraft trajectory more delicately than possible with thrusters. Minor errors are greatly amplified by gravity assist maneuvers, so using radiation pressure to make very small corrections saved large amounts of propellant.

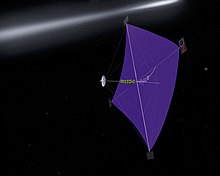

Interstellar flight

In the 1970s, Robert Forward proposed two beam-powered propulsion schemes using either lasers or masers to push giant sails to a significant fraction of the speed of light.[23]

In Rocheworld, Forward described a light sail propelled by super lasers. As the starship neared its destination, the outer portion of the sail would detach. The outer sail would then refocus and reflect the lasers back onto a smaller, inner sail. This would provide braking thrust to stop the ship in the destination star system.

Both methods pose monumental engineering challenges. The lasers would have to operate for years continuously at gigawatt strength. Forward's solution to this requires enormous solar panel arrays to be built at or near the planet Mercury. A planet-sized mirror or fresnel lens would be needed several dozen astronomical units from the Sun to keep the lasers focused on the sail. The giant braking sail would have to act as a precision mirror to focus the braking beam onto the inner "deceleration" sail.

A potentially easier approach would be to use a maser to drive a "solar sail" composed of a mesh of wires with the same spacing as the wavelength of the microwaves, since the manipulation of microwave radiation is somewhat easier than the manipulation of visible light. The hypothetical "Starwisp" interstellar probe design[24][25] would use microwaves, rather than visible light, to push it. Masers spread out more rapidly than optical lasers owing to their longer wavelength, and so would not have as long an effective range.

Masers could also be used to power a painted solar sail, a conventional sail coated with a layer of chemicals designed to evaporate when struck by microwave radiation.[26] The momentum generated by this evaporation could significantly increase the thrust generated by solar sails, as a form of lightweight ablative laser propulsion.

To further focus the energy on a distant solar sail, Forward proposed a lens designed as a large zone plate. This would be placed at a location between the laser or maser and the spacecraft.[23]

Another more physically realistic approach would be to use the light from the Sun to accelerate.[27] The ship would first drop into an orbit making a close pass to the Sun, to maximize the solar energy input on the sail, then the ship would begin to accelerate away from the system using the light from the Sun to keep accelerating. Acceleration will drop approximately as the inverse square of the distance from the Sun, and beyond some distance, the ship would no longer receive enough light to accelerate it significantly, but would maintain its course due to inertia. When nearing the target star, the ship could turn its sails toward it and begin to use the outward acceleration to decelerate. Additional forward and reverse thrust could be achieved with more conventional means of propulsion such as rockets.

Similar solar sailing launch and capture were suggested for directed panspermia to expand life in other solar system. Velocities of 0.0005 c could be obtained by solar sails carrying 10 kg payloads, using thin solar sail vehicles with effective areal densities of 0.1 g/m2 with thin sails of 0.1 µm thickness and sizes on the order of one square kilometer. Alternatively, swarms of 1 mm capsules can be launched on solar sails with radii of 42 cm, each carrying 10,000 capsules of a hundred million extremophile microorganisms to seed life in diverse target environments.[28][29]

Deorbiting artificial satellites

Small solar sails have been proposed to accelerate the deorbiting of small artificial satellites from Earth orbits. Satellites in low Earth orbit can use a combination of solar pressure on the sail and increased atmospheric drag to accelerate satellite reentry.[30] A de-orbit sail developed at Cranfield University is part of the UK satellite TechDemoSat-1, launched in 2014, and is expected to be deployed at the end of the satellite's five-year useful life. The sail's purpose is to bring the satellite out of orbit over a period of about 25 years.[31] In July 2015 British 3U CubeSat called DeorbitSail was launched into space with the purpose of testing 16 m2 deorbit strucutre,[32] but eventually it failed to deploy it.[33] There is also a student 2U CubeSat mission called PW-Sat2 planned to launch in 2017 that will test 4 m2 deorbit sail.[34]

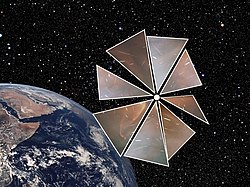

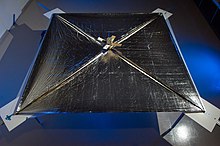

Sail configurations

IKAROS, launched in 2010, was the first practical solar sail vehicle. As of 2015, it was still under thrust, proving the practicality of a solar sail for long-duration missions.[35] It is spin-deployed, with tip-masses in the corners of its square sail. The sail is made of thin polyimide film, with evaporated aluminium on it. It steers with electrically-controlled liquid crystal panels. The sail slowly spins, and these panels turn on and off to control the attitude of the vehicle. When on, they diffuse light, reducing the momentum transfer to that part of the sail. When off, the sail reflects more light, transferring more momentum. In that way, they turn the sail.[36] Thin-film solar cells are also integrated into the sail, powering the spacecraft. The design is very reliable, because spin deployment, which is preferable for large sails, simplified the mechanisms to unfold the sail and the LCD panels have no moving parts.

Parachutes have very low mass, but a parachute is not a workable configuration for a solar sail. Analysis shows that a parachute configuration would collapse from the forces exerted by shroud lines, since radiation pressure does not behave like aerodynamic pressure, and would not act to keep the parachute open.[37]

Eric Drexler[38] proposed very high thrust-to-mass solar sails, and made prototypes of the sail material. His sail would use panels of thin aluminium film (30 to 100 nanometres thick) supported by a tensile structure. The sail would rotate and would have to be continually under thrust. He made and handled samples of the film in the laboratory, but the material was too delicate to survive folding, launch, and deployment. The design planned to rely on space-based production of the film panels, joining them to a deploy-able tension structure. Sails in this class would offer high area per unit mass and hence accelerations up to "fifty times higher" than designs based on deploy-able plastic films.[38]

The highest thrust-to-mass designs for ground-assembled deploy-able structures are square sails with the masts and guy lines on the dark side of the sail. Usually there are four masts that spread the corners of the sail, and a mast in the center to hold guy-wires. One of the largest advantages is that there are no hot spots in the rigging from wrinkling or bagging, and the sail protects the structure from the Sun. This form can, therefore, go close to the Sun for maximum thrust. Most designs steer with small moving sails on the ends of the spars.[39]

In the 1970s JPL studied many rotating blade and ring sails for a mission to rendezvous with Halley's Comet. The intention was to stiffen the structures using angular momentum, eliminating the need for struts, and saving mass. In all cases, surprisingly large amounts of tensile strength were needed to cope with dynamic loads. Weaker sails would ripple or oscillate when the sail's attitude changed, and the oscillations would add and cause structural failure. The difference in the thrust-to-mass ratio between practical designs was almost nil, and the static designs were easier to control.[39]

JPL's reference design was called the "heliogyro". It had plastic-film blades deployed from rollers and held out by centrifugal forces as it rotated. The spacecraft's attitude and direction were to be completely controlled by changing the angle of the blades in various ways, similar to the cyclic and collective pitch of a helicopter. Although the design had no mass advantage over a square sail, it remained attractive because the method of deploying the sail was simpler than a strut-based design.[39]

Heliogyro design is similar to the blades on a helicopter. The design is faster to manufacture due to lightweight centrifugal stiffening of sails. Also, they are highly efficient in cost and velocity because the blades are lightweight and long. Unlike the square and spinning disk designs, heliogyro is easier to deploy because the blades are compacted on a reel. The blades roll out when they are deploying after the ejection from the spacecraft. As the heliogyro travels through space the system spins around because of the centrifugal acceleration. Finally, payloads for the space flights are placed in the center of gravity to even out the distribution of weight to ensure stable flight.[39]

JPL also investigated "ring sails" (Spinning Disk Sail in the above diagram), panels attached to the edge of a rotating spacecraft. The panels would have slight gaps, about one to five percent of the total area. Lines would connect the edge of one sail to the other. Masses in the middles of these lines would pull the sails taut against the coning caused by the radiation pressure. JPL researchers said that this might be an attractive sail design for large manned structures. The inner ring, in particular, might be made to have artificial gravity roughly equal to the gravity on the surface of Mars.[39]

A solar sail can serve a dual function as a high-gain antenna.[40] Designs differ, but most modify the metalization pattern to create a holographic monochromatic lens or mirror in the radio frequencies of interest, including visible light.[40]

Electric solar wind sail

Pekka Janhunen from FMI has invented a type of solar sail called the electric solar wind sail.[41] Mechanically it has little in common with the traditional solar sail design. The sails are replaced with straightened conducting tethers (wires) placed radially around the host ship. The wires are electrically charged to create an electric field around the wires. The electric field extends a few tens of metres into the plasma of the surrounding solar wind. The solar electrons are reflected by the electric field (like the photons on a traditional solar sail). The radius of the sail is from the electric field rather than the actual wire itself, making the sail lighter. The craft can also be steered by regulating the electric charge of the wires. A practical electric sail would have 50–100 straightened wires with a length of about 20 km each.[citation needed]

Electric solar wind sails can adjust their electrostatic fields and sail attitudes.

Magnetic sail

A magnetic sail would also employ the solar wind. However, the magnetic field deflects the electrically charged particles in the wind. It uses wire loops, and runs a static current through them instead of applying a static voltage.[42]

All these designs maneuver, though the mechanisms are different.

Magnetic sails bend the path of the charged protons that are in the solar wind. By changing the sails' attitudes, and the size of the magnetic fields, they can change the amount and direction of the thrust.

Sail making

Materials

The most common material in current designs is a thin layer of aluminum coating on a polymer (plastic) sheet, such as aluminized 2 µm Kapton film. The polymer provides mechanical support as well as flexibility, while the thin metal layer provides the reflectivity. Such material resists the heat of a pass close to the Sun and still remains reasonably strong. The aluminium reflecting film is on the Sun side. The sails of Cosmos 1 were made of aluminized PET film (Mylar).

Drexler developed a concept for a sail in which the polymer was removed. The material developed for the Drexler solar sail was a thin aluminium film with a baseline thickness of 0.1 µm, to be fabricated by vapor deposition in a space-based system. Drexler used a similar process to prepare films on the ground. As anticipated, these films demonstrated adequate strength and robustness for handling in the laboratory and for use in space, but not for folding, launch, and deployment.

Research by Geoffrey Landis in 1998–1999, funded by the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts, showed that various materials such as alumina for laser lightsails and carbon fiber for microwave pushed lightsails were superior sail materials to the previously standard aluminium or Kapton films.[43]

In 2000, Energy Science Laboratories developed a new carbon fiber material that might be useful for solar sails.[44][45] The material is over 200 times thicker than conventional solar sail designs, but it is so porous that it has the same mass. The rigidity and durability of this material could make solar sails that are significantly sturdier than plastic films. The material could self-deploy and should withstand higher temperatures.

There has been some theoretical speculation about using molecular manufacturing techniques to create advanced, strong, hyper-light sail material, based on nanotube mesh weaves, where the weave "spaces" are less than half the wavelength of light impinging on the sail. While such materials have so far only been produced in laboratory conditions, and the means for manufacturing such material on an industrial scale are not yet available, such materials could mass less than 0.1 g/m2,[46] making them lighter than any current sail material by a factor of at least 30. For comparison, 5 micrometre thick Mylar sail material mass 7 g/m2, aluminized Kapton films have a mass as much as 12 g/m2,[39] and Energy Science Laboratories' new carbon fiber material masses 3 g/m2.[44]

The least dense metal is lithium, about 5 times less dense than aluminium. Fresh, unoxidized surfaces are reflective. At a thickness of 20 nm, lithium has an area density of 0.011 g/m2. A high-performance sail could be made of lithium alone at 20 nm (no emission layer). It would have to be fabricated in space and not used to approach the Sun. In the limit, a sail craft might be constructed with a total areal density of around 0.02 g/m2, giving it a lightness number of 67 and ac of about 400 mm/s2. Magnesium and beryllium are also potential materials for high-performance sails. These 3 metals can be alloyed with each other and with aluminium.[2]

Reflection and emissivity layers

Aluminium is the common choice for the reflection layer. It typically has a thickness of at least 20 nm, with a reflectivity of 0.88 to 0.90. Chromium is a good choice for the emission layer on the face away from the Sun. It can readily provide emissivity values of 0.63 to 0.73 for thicknesses from 5 to 20 nm on plastic film. Usable emissivity values are empirical because thin-film effects dominate; bulk emissivity values do not hold up in these cases because material thickness is much thinner than the emitted wavelengths.[47]

Fabrication

Sails are fabricated on Earth on long tables where ribbons are unrolled and joined to create the sails. Sail material needed to have as little weight as possible because it would require the use of the shuttle to carry the craft into orbit. Thus, these sails are packed, launched, and unfurled in space.[48]

In the future, fabrication could take place in orbit inside large frames that support the sail. This would result in lower mass sails and elimination of the risk of deployment failure.

Operations

Changing orbits

Sailing operations are simplest in interplanetary orbits, where attitude changes are done at low rates. For outward bound trajectories, the sail force vector is oriented forward of the Sun line, which increases orbital energy and angular momentum, resulting in the craft moving farther from the Sun. For inward trajectories, the sail force vector is oriented behind the Sun line, which decreases orbital energy and angular momentum, resulting in the craft moving in toward the Sun. It is worth noting that only the Sun's gravity pulls the craft toward the Sun—there is no analog to a sailboat's tacking to windward. To change orbital inclination, the force vector is turned out of the plane of the velocity vector.

In orbits around planets or other bodies, the sail is oriented so that its force vector has a component along the velocity vector, either in the direction of motion for an outward spiral, or against the direction of motion for an inward spiral.

Trajectory optimizations can often require intervals of reduced or zero thrust. This can be achieved by rolling the craft around the Sun line with the sail set at an appropriate angle to reduce or remove the thrust.[49]

Swing-by Maneuvers

A close solar passage can be used to increase a craft's energy. The increased radiation pressure combines with the efficacy of being deep in the Sun's gravity well to substantially increase the energy for runs to the outer Solar System. The optimal approach to the Sun is done by increasing the orbital eccentricity while keeping the energy level as high as practical. The minimum approach distance is a function of sail angle, thermal properties of the sail and other structure, load effects on structure, and sail optical characteristics (reflectivity and emissivity). A close passage can result in substantial optical degradation. Required turn rates can increase substantially for a close passage. A sail craft arriving at a star can use a close passage to reduce energy, which also applies to a sail craft on a return trip from the outer Solar System.

A lunar swing-by can have important benefits for trajectories leaving from or arriving at Earth. This can reduce trip times, especially in cases where the sail is heavily loaded. A swing-by can also be used to obtain favorable departure or arrival directions relative to Earth.

A planetary swing-by could also be employed similar to what is done with coasting spacecraft, but good alignments might not exist due to the requirements for overall optimization of the trajectory.[50]

Smart lines

A smart line could be a critical element of sailing operations. As with maritime ships, lines are essential for a wide range of uses. One difference is that some lines may be very long and need to be self-guiding. The lines could extend from and retract into the sail craft.

A maneuverable grappling device can be used at the end of a line to place or pick up payload containers, to secure a ship to a structure such as a station, to pick up samples from an asteroid or comet, or to engage in towing. The maneuvering unit is like a small spacecraft, with many of the same sensors and control systems. It could draw power from and communicate with the sail craft through the line. These operations could be done autonomously.

Lines a few hundred kilometers long may be used to move a ship from a space station to an orbit farther out where it could begin sailing.[51]

Towing

Smart lines can enable towing operations by being able to attach to or release objects at the remote end of the line. Attached objects might be pulled in to the body of the sailer or remain at the end of the deployed line. Objects to be towed may have attachment points that allow multiple sail craft to engage in the towing. Towing operations can include deflecting large bodies that pose a hazard to Earth, bringing natural bodies to Earth or other sites for resource recovery, and transporting disabled spacecraft or other structures.

To tow or deflect a large body, poles can be inserted on the spin axis of the body. Sail craft can attach to the embedded poles using smart lines. Slip rings enable the craft to tow without the lines getting wrapped up as a result of rotation of the body.[49][52]

Projects operating or completed

IKAROS 2010

On 21 May 2010, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched the world's first interplanetary solar sail spacecraft "IKAROS" (Interplanetary Kite-craft Accelerated by Radiation Of the Sun) to Venus.[53]

JAXA successfully tested IKAROS in 2010. The goal was to deploy and control the sail and, for the first time, to determine the minute orbit perturbations caused by light pressure. Orbit determination was done by the nearby AKATSUKI probe from which IKAROS detached after both had been brought into a transfer orbit to Venus. The total effect over the six month' flight was 100 m/s.[54]

Until 2010, no solar sails had been successfully used in space as primary propulsion systems. On 21 May 2010, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched the IKAROS (Interplanetary Kite-craft Accelerated by Radiation Of the Sun) spacecraft, which deployed a 200 m2 polyimide experimental solar sail on June 10.[55][56][57] In July, the next phase for the demonstration of acceleration by radiation began. On 9 July 2010, it was verified that IKAROS collected radiation from the Sun and began photon acceleration by the orbit determination of IKAROS by range-and-range-rate (RARR) that is newly calculated in addition to the data of the relativization accelerating speed of IKAROS between IKAROS and the Earth that has been taken since before the Doppler effect was utilized.[58] The data showed that IKAROS appears to have been solar-sailing since 3 June when it deployed the sail.

IKAROS has a diagonal spinning square sail 14×14 m (196 m2) made of a 7.5-micrometre (0.0075 mm) thick sheet of polyimide. The polyimide sheet had a mass of about 10 grams per square metre. A thin-film solar array is embedded in the sail. Eight LCD panels are embedded in the sail, whose reflectance can be adjusted for attitude control.[59][60] IKAROS spent six months traveling to Venus, and then began a three-year journey to the far side of the Sun.[61]

Attitude (orientation) control

Both the Mariner 10 mission, which flew by the planets Mercury and Venus, and the MESSENGER mission to Mercury demonstrated the use of solar pressure as a method of attitude control in order to conserve attitude-control propellant.

Hayabusa also used solar pressure on its solar paddles as a method of attitude control to compensate for broken reaction wheels and chemical thruster.

MTSAT-1R (Multi-Functional Transport Satellite )'s solar sail counteracts the torque produced by sunlight pressure on the solar array. The trim tab on the solar array makes small adjustments to the torque balance.

Sail deployment tests

NASA has successfully tested deployment technologies on small scale sails in vacuum chambers.[62]

On February 4, 1993, the Znamya 2, a 20-meter wide aluminized-mylar reflector, was successfully deployed from the Russian Mir space station. Although the deployment succeeded, propulsion was not demonstrated. A second test, Znamya 2.5, failed to deploy properly.

In 1999, a full-scale deployment of a solar sail was tested on the ground at DLR/ESA in Cologne.[63]

On August 9, 2004, the Japanese ISAS successfully deployed two prototype solar sails from a sounding rocket. A clover-shaped sail was deployed at 122 km altitude and a fan-shaped sail was deployed at 169 km altitude. Both sails used 7.5-micrometer film. The experiment purely tested the deployment mechanisms, not propulsion.[64]

Solar sail propulsion attempts

A joint private project between Planetary Society, Cosmos Studios and Russian Academy of Science made two sail testing attempts: in 2001 a suborbital prototype test failed because of rocket failure; and in June 21, 2005, Cosmos 1 launched from a submarine in the Barents Sea, but the Volna rocket failed, and the spacecraft failed to reach orbit. They intended to use the sail to gradually raise the spacecraft to a higher Earth orbit over a mission duration of one month. The launch attempt sparked public interest according to Louis Friedman, "I saw a nice demonstration of public interest in human spaceflight...At the kiosk on one of the streets I noticed a newspaper with an article about our launch...and was delighted to see the best picture capturing the vision of solar sail flight"[65] Despite the failed launch attempt of Cosmos 1, The Planetary Society received applause for their efforts from the space community and sparked a rekindled interest in solar sail technology.

A 15-meter-diameter solar sail (SSP, solar sail sub payload, soraseiru sabupeiro-do) was launched together with ASTRO-F on a M-V rocket on February 21, 2006, and made it to orbit. It deployed from the stage, but opened incompletely.[66]

NanoSail-D 2010

A team from the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (Marshall), along with a team from the NASA Ames Research Center, developed a solar sail mission called NanoSail-D, which was lost in a launch failure aboard a Falcon 1 rocket on 3 August 2008.[67][68] The second backup version, NanoSail-D2, also sometimes called simply NanoSail-D,[69] was launched with FASTSAT on a Minotaur IV on November 19, 2010, becoming NASA's first solar sail deployed in low earth orbit. The objectives of the mission were to test sail deployment technologies, and to gather data about the use of solar sails as a simple, "passive" means of de-orbiting dead satellites and space debris.[70] The NanoSail-D structure was made of aluminium and plastic, with the spacecraft massing less than 10 pounds (4.5 kg). The sail has about 100 square feet (9.3 m2) of light-catching surface. After some initial problems with deployment, the solar sail was deployed and over the course of its 240-day mission reportedly produced a "wealth of data" concerning the use of solar sails as passive deorbit devices.[71]

NASA launched the second NanoSail-D unit stowed inside the FASTSAT satellite on the Minotaur IV on November 19, 2010. The ejection date from the FASTSAT microsatellite was planned for December 6, 2010, but deployment only occurred on January 20, 2011.[72]

LightSail-A

On Carl Sagan's 75th birthday (November 9, 2009) the Planetary Society announced plans[73] to make three further attempts, dubbed LightSail-1, -2, and -3.[74] The new design will use a 32 m2 Mylar sail, deployed in four triangular segments like NanoSail-D.[74] The launch configuration is a 3U CubeSat format, and as of 2015, it is scheduled as a secondary payload for a 2016 launch on the first SpaceX Falcon Heavy launch.[75] The Planetary Society of the United States initiated a short test of an artificial satellite "LightSail-A" that launched on 20 May 2015.[76] The purpose of the test is to allow a full checkout of the satellite's systems in advance of the main 2016 mission, LightSail-1.

Projects in development or proposed

Despite the losses of Cosmos 1 and NanoSail-D (which were due to failure of their launchers), scientists and engineers around the world remain encouraged and continue to work on solar sails. While most direct applications created so far intend to use the sails as inexpensive modes of cargo transport, some scientists are investigating the possibility of using solar sails as a means of transporting humans. This goal is strongly related to the management of very large (i.e. well above 1 km2) surfaces in space and the sail making advancements. Manned space flight utilizing solar sails is still in the development state of infancy.

Sunjammer 2015

A technology demonstration sail craft, dubbed Sunjammer, was in development with the intent to prove the viability and value of sailing technology.[77] Sunjammer had a square sail, 124 feet (38 meters) wide on each side (total area 13,000 sq ft or 1,208 sq m). It would have traveled from the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrangian point 900,000 miles from Earth (1.5 million km) to a distance of 1,864,114 miles (3 million kilometers).[78] The demonstration was expected to launch on a Falcon 9 in January 2015.[79] It would have been a secondary payload, released after the placement of the DSCOVR climate satellite at the L1 point.[79] Citing a lack of confidence in its contractor's ability to deliver, the mission was cancelled in October 2014.[80]

Gossamer deorbit sail

As of December 2013[update], the European Space Agency (ESA) has a proposed deorbit sail, named "Gossamer", that would be intended to be used to accelerate the deorbiting of small (less than 700 kilograms (1,500 lb)) artificial satellites from low-Earth orbits. The launch mass is 2 kilograms (4.4 lb) with a launch volume of only 15×15×25 centimetres (0.49×0.49×0.82 ft). Once deployed, the sail would expand to 5 by 5 metres (16 ft × 16 ft) and would use a combination of solar pressure on the sail and increased atmospheric drag to accelerate satellite reentry.[30]

NEA Scout

The Near-Earth Asteroid Scout (NEA Scout) is a mission being jointly developed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), consisting of a controllable low-cost CubeSat solar sail spacecraft capable of encountering near-Earth asteroids (NEA).[81] Four 7 m booms would deploy, unfurling the 83 m2 aluminized polyimide solar sail.[82][83][84] In 2015, NASA announced it had selected NEA Scout to launch as one of several secondary payloads aboard EM-1, the first flight of the agency's heavy-lift SLS launch vehicle.[85]

In science fiction

The earliest reference to solar sailing was in Jules Verne's 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon,[4] only a year after Maxwell's equations were published, in which he wrote "... light or electricity will probably be the mechanical agent... [by which] we shall one day travel to the moon, the planets, and the stars.[5][86] The next known publication came more than 20 years later when Georges Le Faure and Henri De Graffigny published a four-volume science fiction novel in 1889, The Extraordinary Adventures of a Russian Scientist, which included a spacecraft propelled by solar pressure.[86] In 1913, B. Krasnogorskii published On the Waves of the Ether. In his story backed by technical calculations, a small, bullet-shaped capsule is surrounded by a circular mirror 35 meters in diameter. It travels through space by means of solar pressure on the mirror.[86]

One of the earliest American stories about light sails is "The Lady Who Sailed the Soul" by Cordwainer Smith, which was published in 1960. In it, a tragedy results from the slowness of interstellar travel by this method. Another example is the 1962 story "Gateway to Strangeness" (also known as "Sail 25") by Jack Vance, in which the outward direction of propulsion poses a life-threatening dilemma. Also in early 20th century literature, Pierre Boulle's Planet of the Apes novel starts with a couple floating in space on a ship propelled and maneuvered by light sails.

Both Arthur C. Clarke and Poul Anderson, independently published distinct stories titled "Sunjammer" in March 1964. Clarke's, published in the March 1964 issue of Boys' Life, depicted a "yacht race" between solar sail spacecraft; Anderson, in the April 1964 issue of Analog Science Fiction / Science Fact, depicts a maintenance crew, servicing space-freighters powered by light sails.

Interstellar travel by using light sails was used in Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle's 1974 The Mote in God's Eye, in which a sail is used as a brake and a weapon. In "The Flight of the Dragonfly", Robert Forward (who also proposed the microwave-pushed Starwisp design) described an interstellar journey using a light driven propulsion system, wherein a part of the sail was broken off and used as a reflector to slow the main spacecraft as it approached its destination. Forward's ideas were developed further in Buzz Aldrin and John Barnes 1996 science fiction novel "Encounter with Tiber", where the alien race 'the tiberians' use a solar sail powered first by a close flybys with Alpha Centauri A and B followed by laser boosting to travel to Earth some 9000 years ago. Their spaceship decelerate by detaching part of the light sail as well as using magnetic braking in the solar wind. Charles Stross's 2005 novel Accelerando.[87] also developed interstellar travel by sail.

In visual media, in the 1982 film Tron, in the computer simulation, a "Solar Sailer" was a craft with butterfly-like sails which moved along focused beams of light. The 1983 episode "Enlightenment" of Doctor Who featured sailing ships in space that used solar wind to fly. In the episode "Explorers" of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine that aired in 1995, a reconstructed, "ancient" Bajoran "light ship" was featured. It was designed to use solar wind to fly out of a Solar System with no engine. In the film Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones one is used by Count Dooku to propel himself across space. A solar sail was also used in James Cameron's Avatar. In the Disney film Treasure Planet, solar sails are used literally as sails for interstellar travel as well as serving for the photovoltaic gathering of energy for the jet propulsion of a steampunk-styled masted sailing ship capable of traveling through space.

See also

References

- ^ Georgevic, R. M. (1973) "The Solar Radiation Pressure Forces and Torques Model", The Journal of the Astronautical Sciences, Vol. 27, No. 1, Jan–Feb. First known publication describing how solar radiation pressure creates forces and torques that affect spacecraft.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jerome Wright (1992), Space Sailing, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers

- ^ Johannes Kepler (1604) Ad vitellionem parali pomena, Frankfort; (1619) De cometis liballi tres , Augsburg

- ^ a b Jules Verne (1865) De la Terre à la Lune (From the Earth to the Moon)

- ^ a b Chris Impey, Beyond: Our Future in Space, W. W. Norton & Company (2015)

- ^ P. Lebedev, 1901, "Untersuchungen über die Druckkräfte des Lichtes", Annalen der Physik, 1901

- ^ Lee, Dillon (2008). "A Celebration of the Legacy of Physics at Dartmouth". Dartmouth Undergraduate Journal of Science. Dartmouth College. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ Svante Arrhenius (1908) Worlds in the Making

- ^ Friedrich Zander's 1925 paper, "Problems of flight by jet propulsion: interplanetary flights", was translated by NASA. See NASA Technical Translation F-147 (1964)

- ^ Urbanczyk, Mgr., "Solar Sails-A Realistic Propulsion for Space Craft", Translation Branch Redstone Scientific Information Center Research and Development Directorate U.S. Army Missile Command Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, 1965.

- ^ JBS Haldane, The Last Judgement, New York and London, Harper & Brothers, 1927.

- ^ J. D. Bernal (1929) The World, the Flesh & the Devil: An Enquiry into the Future of the Three Enemies of the Rational Soul

- ^ "Relativistic Momentum". Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- ^ a b Wright, Appendix A

- ^ Kopp, G.; Lean, J. L. (2011). "A new, lower value of total solar irradiance: Evidence and climate significance". Geophysical Research Letters 38. doi:10.1029/2010GL0457770.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McInnes, C. R. and Brown, J. C. (1989) Solar Sail Dynamics with an Extended Source of Radiation Pressure, International Astronautical Federation, IAF-89-350, October.

- ^ Wright, Appendix B.

- ^ http://www.swpc.noaa.gov/SWN/index.html Archived 2014-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wright, ibid., Ch 6 and Appendix B.

- ^ a b Maccone, Claudio. "The Sun as a Gravitational Lens : A Target for Space Missions A Target for Space Missions Reaching 550 AU to 1000 AU" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Paul Gilster (2008-11-12). "An Inflatable Sail to the Oort Cloud". Centauri-dreams.org. Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- ^ "MESSENGER Sails on Sun's Fire for Second Flyby of Mercury". 2008-09-05.

On September 4, the MESSENGER team announced that it would not need to implement a scheduled maneuver to adjust the probe's trajectory. This is the fourth time this year that such a maneuver has been called off. The reason? A recently implemented navigational technique that makes use of solar-radiation pressure (SRP) to guide the probe has been extremely successful at maintaining MESSENGER on a trajectory that will carry it over the cratered surface of Mercury for a second time on October 6.

- ^ a b Forward, R.L. (1984). "Roundtrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser-Pushed Lightsails". J Spacecraft. 21 (2): 187–195. Bibcode:1984JSpRo..21..187F. doi:10.2514/3.8632.

- ^ Forward, Robert L., "Starwisp: An Ultralight Interstellar Probe,” J. Spacecraft and Rockets, Vol. 22, May–June 1985, pp. 345-350.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A., "Microwave Pushed Interstellar Sail: Starwisp Revisited," paper AIAA-2000-3337, 36th Joint Propulsion Conference, Huntsville AL, July 17–19, 2000.

- ^ "Earth To Mars in a Month With Painted Solar Sail". SPACE.com. 2005-02-11. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ^ "Solar Sail Starships:Clipper Ships of the Galaxy," chapter 6, Eugene F. Mallove and Gregory L. Matloff, The Starflight Handbook: A Pioneer's Guide to Interstellar Travel, pp. 89-106, John Wiley & Sons, 1989. ISBN 978-0471619123

- ^ Meot-Ner (Mautner), Michael N.; Matloff, Gregory L. (1979). "Directed panspermia: A technical and ethical evaluation of seeding nearby solar systems" (PDF). Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 32: 419–423. Bibcode:1979JBIS...32..419M. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mautner, Michael N. (1995). "Directed panspermia. 2. Technological advances toward seeding other solar systems, and the foundations of panbiotic ethics". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 48: 435–440.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (2013-12-26). "ESA Developing Solar Sail to Safely Deorbit Satellites". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ^ "22,295,864 amazing things you need to know about the UK’s newest satellite". Innovate UK.

- ^ "Mission". www.surrey.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ "DeorbitSail Update and Initial Camera Image". AMSAT-UK. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ "PW-Sat2 gets 180 000 € to fund the launch". PW-Sat2: Polish student satellite project. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ "Small Solar Power Sail Demonstrator machine (小型ソーラー電力セイル実証機)" (PDF). JAXA. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ JAXA. "Small Solar Power Sail Demonstrator 'IKAROS' Successful Attitude Control by Liquid Crystal Device". JAXA. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Wright, ibid., p. 71, last paragraph

- ^ a b Drexler, K. E. (1977). "Design of a High Performance Solar Sail System, MS Thesis," (PDF). Dept. of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Massachusetts Institute of Techniology, Boston.

- ^ a b c d e f "Design & Construction". NASA JPL. Archived from the original on 2005-03-11.

- ^ a b Khayatian, Rahmatsamii, Porgorzelski, UCLA and JPL. "An Antenna Concept Integrated with Future Solar Sails" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NASA. "Solar Sails Could Send Spacecraft 'Sailing' Through Space".

- ^ http://www.niac.usra.edu/files/library/meetings/fellows/nov99/320Zubrin.pdf

- ^ Geoffrey A. Landis, Ohio Aerospace Institute (1999). "Advanced Solar- and Laser-pushed Lightsail Concepts" (PDF).

- ^ a b SPACE.com Exclusive: Breakthrough In Solar Sail Technology Archived 2014-09-07 at the Wayback Machine (DEAD LINK!)

- ^ http://sbir.nasa.gov/SBIR/abstracts/99/sbir/phase1/SBIR-99-1-25.02-2034.html (NASA SBIR page) retrieved 25 Dec, 2015

- ^ "Researchers produce strong, transparent carbon nanotube sheets". Physorg.com. 2005-08-18. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ^ Wright, ibid. Ch 4

- ^ Rowe, W. m. 'Sail film materials and supporting structure for a solar sail, a preliminary design, volume 4." Jet Propulsion Lab. California, Pasadena, California.

- ^ a b Wright, ibid., chapter 1.

- ^ Wright, ibid., Ch 6 and Appendix C.

- ^ Smart lines for sailing operations

- ^ "Asteroid deflection/towing".

- ^ "IKAROS Project|JAXA Space Exploration Center". Jspec.jaxa.jp. 2010-05-21. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ^ Tsuda, Yuichi (2011). "Solar Sail Navigation Technology of IKAROS". JAXA.

- ^ "Small Solar Power Sail Demonstrator 'IKAROS' Successful Solar Sail Deployment". JAXA website press release. Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ "News briefing: 27 May 2010". NatureNEWS. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ Samantha Harvey (21 May 2010). "Solar System Exploration: Missions: By Target: Venus: Future: Akatsuki". NASA. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ "About the confirmation of photon acceleration of "IKAROS" the small solar-sail demonstrating craft (There is not English press release yet)". JAXA website press release. Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 2010-07-09. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "Small Solar Power Sail Demonstrator". JAXA. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ "IKAROS Project". JAXA. 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (2010-05-17). "Space yacht Ikaros ready to cast off for far side of the Sun". London: The Guardian Weekly. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ "Solar Sails Could Send Spacecraft 'Sailing' Through Space".

- ^ "Full-scale deployment test of the DLR/ESA Solar Sail" (PDF). 1999.

- ^ "Cosmos 1 - Solar Sail (2004) Japanese Researchers Successfully Test Unfurling of Solar Sail on Rocket Flight". 2004.

- ^ Friedman Louis, "The Rise and Fall of Cosmos 1", Http://sail.planetary.org/story-part-2.html

- ^ "SSSat 1, 2". Space.skyrocket.de. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ^ NASASpaceflight.com - SpaceX Falcon I FAILS during first stage flight Archived 2008-12-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NASA to Attempt Historic Solar Sail Deployment". NASA. 2008-06-26.

- ^ "NASA Chat: First Solar Sail Deploys in Low-Earth Orbit". NASA. 2011-01-27. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

Sometimes the satellite is called NanoSail-D and sometimes NanoSail-D2. ... Dean: The project is just NanoSail-D. NanoSail-D2 is the serial #2 version.

- ^ Nasa report on mission

- ^ Nasa report on mission

- ^ "NASA - NanoSail-D Home Page". Nasa.gov. 2011-01-21. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ OVERBYE, DENNIS (November 9, 2009). "Setting Sail Into Space, Propelled by Sunshine". Retrieved 18 May 2012.

Planetary Society, ... the next three years, ... series of solar-sail spacecraft dubbed LightSails

- ^ a b "LightSail Mission FAQ". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Nye, Bill. Kickstart LightSail. Event occurs at 3:20. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Blastoff! X-37B Space Plane and LightSail Solar Sail Go Into Orbit".

- ^ "Nasa Solar Sail Demonstration". www.nasa.gov.

- ^ Leonard David (January 31, 2013). "NASA to Launch World's Largest Solar Sail in 2014". Space.com. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Mike Wall (June 13, 2013). "World's Largest Solar Sail to Launch in November 2014". Space.com. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Leone, Dan (October 17, 2014). "NASA Nixes Sunjammer Mission, Cites Integration, Schedule Risk". spacenews.com.

- ^ "NEA Scout". NASA. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ McNutt, Leslie; Castillo-Rogez, Julie (2014). "Near-Earth Asteroid Scout" (PDF). NASA. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter Dirk (13 April 2015). "NEA-Scout". Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ^ Castillo-Rogez, Julie; Abell, Paul. "Near Earth Asteroid Scout Mission" (PDF). NASA. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (November 27, 2015). "NASA identifies secondary payloads for SLS's EM-1 mission". NASAspaceflight.

- ^ a b c Jerome Wright, Space Sailing, Activity and History (accessed 24 Dec 2015)

- ^ Stross, Charles (2005). "Accelerando". Antipope.org. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

Bibliography

- G. Vulpetti, Fast Solar Sailing: Astrodynamics of Special Sailcraft Trajectories, ;;Space Technology Library Vol. 30, Springer, August 2012, (Hardcover) http://www.springer.com/engineering/mechanical+engineering/book/978-94-007-4776-0, (Kindle-edition), ASIN: B00A9YGY4I

- G. Vulpetti, L. Johnson, G. L. Matloff, Solar Sails: A Novel Approach to Interplanetary Flight, Springer, August 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-34404-1

- J. L. Wright, Space Sailing, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, London, 1992; Wright was involved with JPL's effort to use a solar sail for a rendezvous with Halley's comet.

- NASA/CR 2002-211730, Chapter IV— presents an optimized escape trajectory via the H-reversal sailing mode

- G. Vulpetti, The Sailcraft Splitting Concept, JBIS, Vol. 59, pp. 48–53, February 2006

- G. L. Matloff, Deep-Space Probes: To the Outer Solar System and Beyond, 2nd ed., Springer-Praxis, UK, 2005, ISBN 978-3-540-24772-2

- T. Taylor, D. Robinson, T. Moton, T. C. Powell, G. Matloff, and J. Hall, "Solar Sail Propulsion Systems Integration and Analysis (for Option Period)", Final Report for NASA/MSFC, Contract No. H-35191D Option Period, Teledyne Brown Engineering Inc., Huntsville, AL, May 11, 2004

- G. Vulpetti, "Sailcraft Trajectory Options for the Interstellar Probe: Mathematical Theory and Numerical Results", the Chapter IV of NASA/CR-2002-211730, The Interstellar Probe (ISP): Pre-Perihelion Trajectories and Application of Holography, June 2002

- G. Vulpetti, Sailcraft-Based Mission to The Solar Gravitational Lens, STAIF-2000, Albuquerque (New Mexico, USA), 30 January – 3 February 2000

- G. Vulpetti, "General 3D H-Reversal Trajectories for High-Speed Sailcraft", Acta Astronautica, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 67–73, 1999

- C. R. McInnes, Solar Sailing: Technology, Dynamics, and Mission Applications, Springer-Praxis Publishing Ltd, Chichester, UK, 1999, ISBN 978-3-540-21062-7

- Genta, G., and Brusa, E., "The AURORA Project: a New Sail Layout", Acta Astronautica, 44, No. 2–4, pp. 141–146 (1999)

- S. Scaglione and G. Vulpetti, "The Aurora Project: Removal of Plastic Substrate to Obtain an All-Metal Solar Sail", special issue of Acta Astronautica, vol. 44, No. 2–4, pp. 147–150, 1999

External links

- "Deflecting Asteroids" by Gregory L. Matloff, IEEE Spectrum, April 2012

- Planetary Society's solar sailing project

- The Solar Photon Sail Comes of Age by Gregory L. Matloff

- NASA Mission Site for NanoSail-D

- NanoSail-D mission: Dana Coulter, "NASA to Attempt Historic Solar Sail Deployment", NASA, June 28, 2008

- Far-out Pathways to Space: Solar Sails from NASA

- Solar Sails Comprehensive collection of solar sail information and references, maintained by Benjamin Diedrich. Good diagrams showing how light sailors must tack.

- U3P Multilingual site with news and flight simulators

- ISAS Deployed Solar Sail Film in Space

- Suggestion of a solar sail with roller reefing, hybrid propulsion and a central docking and payload station.

- Interview with NASA's JPL about solar sail technology and missions

- Website with technical pdf-files about solar-sailing, including NASA report and lectures at Aerospace Engineering School of Rome University

- Advanced Solar- and Laser-pushed Lightsail Concepts

- Andrews, D. G. (2003). "Interstellar Transportation using Today's Physics" (PDF). AIAA Paper 2003-4691. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

- www.aibep.org: Official site of American Institute of Beamed Energy Propulsion

- Space Sailing Sailing ship concepts, operations, and history of concept

- Bernd Dachwald's Website Broad information on sail propulsion and missions