Space Pilot 3000

| "Space Pilot 3000" | |

|---|---|

| Futurama episode | |

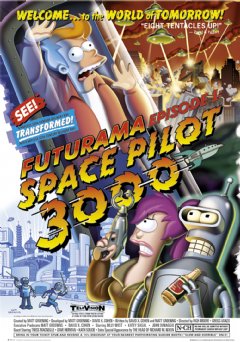

Promotional Artwork for this episode. | |

| Directed by | Rich Moore Gregg Vanzo |

| Written by | David X. Cohen Matt Groening |

| Original air date | March 28, 1999 |

| Episode features | |

| Opening cartoon | Little Buck Cheeser by MGM (1937) |

"Space Pilot 3000" is the pilot episode of Futurama, which originally aired in North America on March 28, 1999 on Fox.[1] The episode focuses on the cryogenic freezing of the series protagonist, Philip J. Fry, and the events when he awakens 1,000 years in the future. Series regulars are introduced and the futuristic setting, inspired by a variety of classic science fiction series from The Jetsons to Star Trek, is revealed. It also sets the stage for many of the events to follow in the series, foreshadowing plot points from the third and fourth seasons.

The episode was written by David X. Cohen and Matt Groening,[1] and directed by Rich Moore and Gregg Vanzo. Dick Clark and Leonard Nimoy guest starred as themselves.[2] The episode generally received good reviews with many reviewers noting that while the episode started slow the series merited further viewing.

Plot

On December 31, 1999, a pizza delivery boy named Philip J. Fry delivers a pizza to "Applied Cryogenics" in New York City. At midnight, Fry accidentally falls into an open cryonic tube and is frozen. He is defrosted on December 31, 2999, in what is now New New York City. He is taken to a fate assignment officer named Leela, a cyclops, who assigns him the computer-determined permanent career of delivery boy. Refusing, Fry flees into the city with Leela in pursuit.

While trying to track down his only living relative, Professor Farnsworth, Fry befriends a suicidal robot named Bender. As they talk at a bar, Fry learns that Bender too has deserted his job of bending girders for suicide booths. Together, they evade Leela and hide in the Head Museum, where they encounter the preserved heads of historical figures. Fry and Bender eventually find themselves underground in the ruins of Old New York.

Leela finally catches Fry and he, depressed that everyone that he knew and loved is dead, tells her that he will accept his career as a delivery boy. Leela unexpectedly sympathizes with Fry — she too is alone, and hates her job — so she quits and joins Fry and Bender as job deserters. The three track down Professor Farnsworth, founder of an intergalactic delivery company called Planet Express. The three deserters, with the help of Professor Farnsworth, evade the police by launching the Planet Express Ship at the stroke of midnight amid the New Year's fireworks. As the year 3000 begins, Farnsworth hires the three as the crew of his ship. Fry cheers at his acquisition of a new job: delivery boy.

Continuity

While the plot of the episode stands on its own it also sets up much of the continuing plot of the series by including Easter eggs for events which do not occur until much later.[1] As Fry falls into the freezer, the scene shows a strange shadow cast on the wall behind him. It is revealed in "The Why of Fry" that the shadow belongs to Nibbler, who intentionally pushes Fry into the freezer as part of a complex plan to save Earth from the Brainspawn in the future. Executive producer David X. Cohen claims that from the very beginning the creators had plans to show a larger conspiracy behind Fry's journey to the future.[3] In the movie Futurama: Bender's Big Score, it is revealed that the spacecraft seen destroying the city while Fry is frozen are piloted by Bender and those chasing him after he steals the Nobel Peace Prize.[4][5]

While Fry and Bender were in the bar, Fry asked Bender why a robot would need to drink; Bender gave the stereotypical alcoholic's response of "I don't need to drink; I can quit anytime I want!" However, later episodes (starting with this season's "I, Roommate") heavily stress the fact that robots do, in fact, need to drink, as alcohol powers their fuel cells. Without alcohol, Bender acts "sober," which is the robot equivalent of acting drunk.

At the end of the episode, Professor Farnsworth offers Fry, Leela, and Bender the Planet Express delivery crew positions. The professor produces the previous crew's career chips from an envelope labeled "Contents of Space Wasp's Stomach". In a later episode "The Sting" the crew encounters the ship of the previous crew in a space bee hive. When discussing this discontinuity in the episode commentary, writer of "The Sting" Patric Verrone states "we made liars out of the pilot".[6]

This episode introduces the fictional technology which allows preserved heads to be kept alive in jars. This technology makes it possible for the characters to interact with celebrities from the then distant past, and is used by the writers to comment on the 20th and 21st centuries in a satirical manner.[2]

Production

In the DVD commentary, Matt Groening notes that beginning any television series is difficult, but he found particular difficulty starting one that took place in the future because of the amount of setup required. As a trade off, they included a lot of Easter eggs in the episode that would pay off in later episodes. He and Cohen point these out throughout the episode.[7] The scene where Fry emerges from a cryonic tube and has his first view of New New York was the first 3D scene worked on by the animation team. It was considered to be a defining point for whether the technique would work or not.[8]

Originally, the first person entering the pneumatic tube transport system declared "J.F.K., Jr. Airport" as his destination. After John F. Kennedy, Jr.'s death in the crash of his private airplane, the line has since been redubbed on all subsequent broadcasts and the DVD release to "Radio City Mutant Hall." The original version was heard only during the pilot broadcast and the first rerun a few months later.[8] According to Groening, the inspiration for the suicide booth was the 1937 Donald Duck cartoon, "Modern Inventions", in which the Duck is faced with—and nearly killed several times by—various push button gadgets in a Museum of the Future.[7]

Cultural references

In their original pitch to Fox, Groening and Cohen stated that they wanted the futuristic setting for the show to be neither "dark and drippy" like Blade Runner, nor "bland and boring" like The Jetsons.[7] They felt that they could not make the future either a utopia or a dystopia because either option would eventually become boring.[8] The creators gave careful consideration to the setting, and the influence of classic science fiction is evident in this episode as a series of references to—and parodies of—easily recognizable films, books and television programs. In the earliest glimpse of the future while Fry is frozen in the cryonic chamber, time is seen passing outside the window until reaching the year 3000. This scene was inspired by a similar scene in the film The Time Machine based on H.G. Wells' novel.[7] When Fry awakens in the year 2999, he is greeted with Terry's catchphrase "Welcome to the world of tomorrow." The scene is a joke at the expense of Futurama's namesake, the Futurama ride at the 1939 World's Fair whose tag line was "The World of Tomorrow".[9]

In addition to the setting, part of the original concept for the show was that there would be a lot of advanced technology similar to that seen in Star Trek, but it would be constantly malfunctioning.[8] The automatic doors at Applied Cryogenics resemble those in Star Trek: The Original Series; however, they malfunction when Fry remarks on this similarity.[10] In another twist, the two policemen who try to arrest Fry at the head museum use weapons which are visually similar to lightsabers used in the Star Wars film series; however, they are functionally more similar to nightsticks.[10] The interaction between the characters was not overlooked. The relationship formed between Fry and Bender in this episode has been compared to the relationship between Will Robinson and the robot in Lost in Space.[11]

Although both Futurama and The Simpsons were created by Matt Groening, overt references to the latter are mostly avoided in Futurama. One of the few exceptions to this rule is the appearance of Blinky, a three-eyed orange fish seen on The Simpsons, as Fry is going through the tube.[7]

Another running gag of the series is Bender's fondness for Olde Fortran malt liquor,[10] named after Olde English 800 malt liquor and the programming language Fortran. The drink was first introduced in this episode and became so closely associated with the character that he was featured with a bottle in both the Rocket USA wind-up toy and the action figure released by Moore Action Collectibles.[12][13]

Broadcast and reception

In a review by Patrick Lee in Science Fiction Weekly based on a viewing of this episode alone, Futurama was deemed not as funny as The Simpsons, particularly as "the satire is leavened with treacly sentimental bits about free will and loneliness". The episode was rated as an "A- pick" and found to "warrant further viewing" despite these concerns.[10] Rob Owen of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette noted that although the episode contained the same skewed humor as The Simpsons, it was not as smart and funny, and he attributed this to the large amount of exposition and character introduction required of a television series pilot, noting that the show was "off to a good start."[14] Andrew Billen of New Statesman found the premise of the episode to be unoriginal, but remained somewhat enthusiastic about the future of the series. While he praised the humorous details of the episode, such as the background scenes while Fry was frozen, he also criticized the show's dependence on in-jokes such as Groening's head being present in the head museum.[15]

In its initial airing, the episode had "unprecedented strong numbers" with a Nielsen rating of 11.2/17 in homes and 9.6/23 in adults 18–49.[16] The Futurama premiere was watched by more people than either its lead-in show (The Simpsons) or the show following it (The X-Files), and it was the number one show among men aged 18–49 and teenagers for the week.[17][18] The episode was ranked in 2006 by IGN as number 14 in their list of the top 25 Futurama episodes.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d Iverson, Dan (2006-07-07). ""Top 25 Futurama Episodes"". IGN. Retrieved 2008-06-15. Cite error: The named reference "IGN" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Booker, M. Keith. Drawn to Television:Prime-Time Animation from The Flintstones to Family Guy. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 115–224. ISBN 0275990192.

- ^ Cohen, David X (2003). Futurama season 4 DVD commentary for the episode "The Why of Fry" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Reed, Phil (2007-12-02). "Review: Bender's Big Score". Noisetosignal.org. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Groening, Matt (2007). Futurama: Bender's Big Score DVD commentary (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Verrone, Patric (2003). Futurama season 4 DVD commentary for the episode "The Sting" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

{{cite AV media}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b c d e Groening, Matt (2003). Futurama season 1 DVD commentary for the episode "Space Pilot 3000" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

{{cite AV media}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b c d Cohen, David X (2003). Futurama season 1 DVD commentary for the episode "Space Pilot 3000" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

{{cite AV media}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Cohen" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "The Original Futurama". Wired. 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d Lee, Patrick (March 22, 1999). ""Futurama: The future's not what it used to be "". Sci Fi Weekly. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ Joyce Millman (1999-03-26). ". . . . . . . that 31st century show . . . . . . ". Salon.com. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Janulewicz, Tom (2000-02-29). "Pushing Tin: Space Toys With Golden-Age Style". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ Huxter, Sean (2001-06-11). "Futurama Action Figures". Sci Fi Weekly. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ Owen, Rob (1999-03-26). "Simpsons meet the Jetsons; 'The Devil's Arithmetic'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Billen, Andrew (1999-09-27). "Laughing matters". New Statesman. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bierbaum, Tom (1999-03-30). "Fox sees 'Futurama' and it works". Variety. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ de Moraes, Lisa (1999-03-31). "`Futurama' Draws Them In". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ ""Futurama" has popular premiere". Animation World Network. 1999-04-04. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)