Square-free integer

In mathematics, a square-free, or quadratfrei, integer is one divisible by no perfect square, except 1. For example, 10 is square-free but 18 is not, as it is divisible by 9 = 32. The smallest positive square-free numbers are

- 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 26, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, ... (sequence A005117 in the OEIS)

Equivalent characterizations

The positive integer n is square-free if and only if in the prime factorization of n, no prime number occurs more than once. Another way of stating the same is that for every prime factor p of n, the prime p does not divide n / p. Yet another formulation: n is square-free if and only if in every factorization n = ab, the factors a and b are coprime. An immediate result of this definition is that all prime numbers are square-free.

The positive integer n is square-free if and only if μ(n) ≠ 0, where μ denotes the Möbius function.

The positive integer n is square-free if and only if all abelian groups of order n are isomorphic, which is the case if and only if all of them are cyclic. This follows from the classification of finitely generated abelian groups.

The integer n is square-free if and only if the factor ring Z / nZ (see modular arithmetic) is a product of fields. This follows from the Chinese remainder theorem and the fact that a ring of the form Z / kZ is a field if and only if k is a prime.

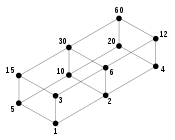

For every positive integer n, the set of all positive divisors of n becomes a partially ordered set if we use divisibility as the order relation. This partially ordered set is always a distributive lattice. It is a Boolean algebra if and only if n is square-free.

The radical of an integer is always square-free: an integer is square-free if it is equal to its radical.

Dirichlet generating function

The Dirichlet generating function for the square-free numbers is

- where ζ(s) is the Riemann zeta function.

This is easily seen from the Euler product

Distribution

Let Q(x) denote the number of square-free (quadratfrei) integers between 1 and x. For large n, 3/4 of the positive integers less than n are not divisible by 4, 8/9 of these numbers are not divisible by 9, and so on. Because these events are independent, we obtain the approximation:

This argument can be made rigorous to yield:

(see pi and big O notation). Under the Riemann hypothesis, the error term can be reduced:[1]

See the race between the number of square-free numbers up to n and round(n/ζ(2)) on the OEIS:

OEIS: A158819 – (Number of square-free numbers ≤ n) minus round(n/ζ(2)). ]

The asymptotic/natural density of square-free numbers is therefore

where ζ is the Riemann zeta function and 1/ζ(2) is approximately 0.6079 (over 3/5 of the integers are square-free).

Likewise, if Q(x,n) denotes the number of n-free integers (e.g. 3-free integers being cube-free integers) between 1 and x, one can show

Encoding as binary numbers

If we represent a square-free number as the infinite product:

then we may take those and use them as bits in a binary number, i.e. with the encoding:

e.g. The square-free number 42 has factorisation 2 × 3 × 7, or as an infinite product: 21 · 31 · 50 · 71 · 110 · 130 · ...; Thus the number 42 may be encoded as the binary sequence ...001011 or 11 decimal. (Note that the binary digits are reversed from the ordering in the infinite product.)

Since the prime factorization of every number is unique, so also is every binary encoding of the square-free integers.

The converse is also true. Since every positive integer has a unique binary representation it is possible to reverse this encoding so that they may be 'decoded' into a unique square-free integer.

Again, for example if we begin with the number 42, this time as simply a positive integer, we have its binary representation 101010. This 'decodes' to become 20 · 31 · 50 · 71 · 110 · 131 = 3 × 7 × 13 = 273.

Among other things, this implies that the set of all square-free integers has the same cardinality as the set of all integers. In turn that leads to the fact that the in-order encodings of the square-free integers are a permutation of the set of all integers.

See sequences A048672 and A064273 in the OEIS

Erdős squarefree conjecture

The central binomial coefficient

is never squarefree for n > 4. This was proven in 1996 by Olivier Ramaré and Andrew Granville.

Squarefree core

The multiplicative function is defined to map positive integers n to t-free numbers by reducing the exponents in the prime power representation modulo t:

The value set of , in particular, are the square-free integers. Their Dirichlet generating functions are

- .

OEIS representatives are OEIS: A007913 (t=2), OEIS: A050985 (t=3) and OEIS: A053165 (t=4).

Notes

- ^ Jia, Chao Hua. "The distribution of square-free numbers", Science in China Series A: Mathematics 36:2 (1993), pp. 154–169. Cited in Pappalardi 2003, A Survey on k-freeness; also see Kaneenika Sinha, "Average orders of certain arithmetical functions", Journal of the Ramanujan Mathematical Society 21:3 (2006), pp. 267–277.

References

- Granville, Andrew; Ramaré, Olivier (1996). "Explicit bounds on exponential sums and the scarcity of squarefree binomial coefficients". Mathematika. 43: 73–107. doi:10.1112/S0025579300011608. MR 1401709. Zbl 0868.11009.

- Guy, Richard K. (2004). Unsolved problems in number theory (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-20860-7. Zbl 1058.11001.

![{\displaystyle Q(x,n)={\frac {x}{\sum _{k=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{k^{n}}}}}+O\left({\sqrt[{n}]{x}}\right)={\frac {x}{\zeta (n)}}+O\left({\sqrt[{n}]{x}}\right).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0ee1f41bd7855734c706b7b8b71544e094e7a5da)