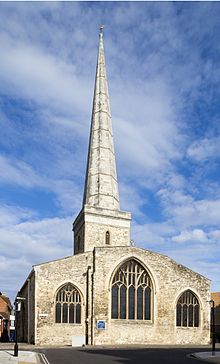

St Michael's Church, Southampton

| St. Michael's Church, Southampton | |

|---|---|

| Church of St. Michael | |

The Parish Church of St Michael, Southampton | |

| 50°53′59″N 1°24′19″W / 50.89959°N 1.40515°W | |

| Location | Southampton, Hampshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | Parish of St Michael's, Southampton |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Founded | 1070 |

| Dedication | St. Michael |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Listed building – Grade I |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Norman |

| Completed | Last major re-building 1872 |

| Specifications | |

| Spire height | 165 ft 0 in (50.29 m) |

| Materials | Ashlar |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Winchester |

| Archdeaconry | Bournemouth |

| Deanery | Southampton |

| Parish | St Michael's, Southampton |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Bishop of Southampton |

| Vicar(s) | Fr David Deboys |

| Priest(s) | Revd Phil Hand, Revd Mohan Uddin |

| Curate(s) | Revd Jackie Sellin |

| Laity | |

| Reader(s) | Duncan Bradley |

| Organist(s) | Keith Davis Director of Music |

| Music group(s) | Cantores Michaelis www.catoresmichaelis.net |

St. Michael the Archangel Church is the oldest building still in use in the city of Southampton, England,[1] founded in 1070. It is the only church still active of the five originally in the medieval walled town.[1] The church is a Grade I Listed building.[2][3]

Location

[edit]The church occupies the east side of St Michael's Square off Bugle Street in the heart of the Old Town, opposite the Tudor House Museum. In medieval times, the Fish Market (now the Tudor Merchant's Hall or Westgate Hall, adjoining the Westgate) was situated in St Michael's Square.[1]

History

[edit]Following the Norman Conquest of England, the town of Southampton was moved west from the original Saxon settlement of Hamwic, around the older St. Mary's Church, to higher ground closer to the River Test.[4] Archaeological evidence has dated the foundation of the church at 1070[5] and the church was dedicated to St. Michael, patron saint of Normandy. The original church was built on a cruciform plan; the earliest parts of the present church are the lower storeys of the central tower.[5]

The first documentary evidence of the existence of St. Michael's was in 1160 when Henry II granted the Chapels of St. Michael, Holyrood, St. Lawrence and All Saints to the monks of St. Denys, who retained the patronage until the dissolution in 1537 when St. Michael's passed to the Crown.[5]

As the town prospered during the Middle Ages, becoming one of the most important ports in England, so did St. Michael's, being at the heart of the thriving medieval town. St. Michael's was enlarged with chapels being added to both sides of the chancel in the 13th century.[5] During the French raids on the town in October 1338, the church was badly damaged by fire, with the wooden buildings attached to it being completely destroyed.[5] The French raids in the Hundred Years' War and the Black Death damaged the prosperity of the town, and it was not until the end of the 14th century that prosperity returned, with the resumption of the wine trade being evidenced by the large number of wine vaults under the old town streets.[5]

In the late 14th century the north aisle of the church was widened, with the south aisle being similarly widened and the west door rebuilt in the 15th century. Thus the church developed into its present almost rectangular shape. The church's first spire was constructed in the 15th century and by the beginning of the 16th century a chantry chapel projected from the south chapel.[5]

From the second half of the 16th century the importance of Southampton as a port declined, together with the prosperity of the town and the parish of St. Michael. As a result, the fabric of the church was neglected to such a degree that the chantry chapel was shut off, to be let as a dwelling house and even as a barber's shop until it was pulled down in about 1880.[5]

It was not until 1836 that centuries of neglect were halted, with the newly installed vicar, Rev. T. L. Shapcott, embarking upon a major reconstruction,[5] involving new pews, raising the floor level, heightening of the aisles and extension westward of the north aisle, reconstruction of the roof to a lower pitch to bring the whole under one gable, insertion of new galleries to the designs of Francis Goodwin and the replacement of the medieval nave arcades by stuccoed brick and cast-iron pillars, making a slim, elegant contrast to the solid rough stonework of the earlier walls.[1] The whole scheme cost the parish £2,390.[5]

In 1872, the Goodwin galleries had to be removed as they were damaging the fabric of the building.[1]

The spire was first built in the 15th century, and reconstructed in 1732.[1] In 1887, to make it a better landmark for shipping, a further 9 ft was added to the blunt shape, bringing it to its present graceful proportions. It is now 165 ft (50 m) high.[5]

In World War II, much of Southampton was devastated by enemy bombing during the blitz. Although the other churches in the central town, Holyrood and All Saints, were both destroyed in 1940, St. Michael's escaped with only minor damage,[5] allegedly because the spire was used by the German bombers as a landmark and their pilots were ordered not to hit it.[6]

In the 1960s, the entire church was restored at a total cost of £36,000, with the work being completed in time for the church's 900th anniversary in 1970.[1]

Description of the church

[edit]Exterior

[edit]The west wall has one of the original Norman pilaster buttresses, a 15th-century doorway and the marks of the original gabled roof line before the roof was raised in 1828.[5]

The south wall has pieces of the cluster of round pillars of the original Norman church, which were removed in 1828 and inserted in the wall when it was heightened. The large arch, which opened into the chantry, is now filled in.[5]

The east wall has 12th-century work in its lower part with the external south-east angle of the 12th-century chancel still projecting from the present wall.[5]

The north wall has a doorway with a well moulded, four-centred arched head and jambs of 15th century date (perhaps removed from the south transept wall when the door under the window was closed up and re-set here in 1828).[5]

The 165 ft high spire is surmounted by a weather vane comprising a gilded cock measuring 3 ft 3in from beak to tail, and 21in high. This was originally placed on top of the spire when this was rebuilt in 1733.[5]

Interior

[edit]The walls average 3 ft 10in in thickness and are pierced towards the chancel, nave and transepts with semi-circular arches of a single square order. The arches are of equal span but are irregularly placed in their respective sides.[5]

The chancel is 22 ft 6in square. The lower part of the east wall is substantially 12th century. There is a triple arch piscina with double "bason" (c.1260) and a 15th-century single piscina.[5]

The north and south chapels, flanking the chancel, open to the chancel by fine arches of two chamfered orders. The south chapel, now used as a vestry, has a four-light east window similar to that in the north chapel. The 15 ft wide arch (now blocked up) leading to the chantry is in the south wall. The organ is raised above the choir vestry (in what was the south transept) which is separated from the south aisle of the nave by a screen, on which is mounted the only medieval woodwork remaining in the church.[5]

The north chapel was originally known as the Mayor's or Corporation Chapel because, until 1835, the mayor was "sworn in" there. From 1677 onwards, the ceremony was performed without a sermon for in that year the mayor and councillors took exception to being abused from the pulpit by the Vicar, Rev. Thomas Butler. The chapel's four-light east window has renewed 15th-century tracery and glass of 1872. In the eastern jamb of the window in the north wall is a merchant's mark, a square sunk panel with a shield bearing a monogram – the sign of the Woolstaplers' Guild. Opposite the north door, there is a 13th-century piscina.[5]

The south wall dates from the 15th century and has two square headed 15th-century windows. The north wall has two-light late 14th-century windows enclosed within acutely pointed heads. To the west of the second window is the blocked north doorway, adjoining the east jamb of which is a 15th-century holy water stoup.[5]

Windows

[edit]

The East Window depicts the five churches of medieval Southampton: St. John's (pulled down in 1708), St. Lawrence (pulled down between the wars), St. Michael's, Holyrood (bombed in 1940) and All Saints' (destroyed by bombing in 1940).[5][7][8]

The West Window depicts St Michael slaying the dragon.[7][9]

Furnishings

[edit]Font

[edit]

The font was made in about 1170 from a single block of black Tournai marble and is one of four such fonts in Hampshire with a further 3 in the rest of England.[1][10] The pillars of the font are made from Purbeck Marble.[10]

Lecterns

[edit]One of the two brass lecterns was rescued from the nearby Holyrood Church during the 1940 blitz and is one of the oldest (14th/early 15th century) and finest in the country,[1] with a beautifully tapering eagle's body and separated wing feathers. The other is a fine brass eagle (c.1450), but of more familiar type; its claws and jewelled eyes are missing.[5]

Tombs and memorials

[edit]The most famous tomb in the church is that of Sir Richard Lyster (c.1480–1554). Lyster was Chief Baron and later Lord Chief Justice of the Common pleas. His tomb was erected in 1567.[5] The tomb is situated in the north-east corner of the church and is a delightful early-Elizabethan example of the use of fluted columns and other classical details.[1]

By the north-east corner of the tower is part of a 12th-century gravestone made from Purbeck Marble, with a carving of a bishop in mass vestments, holding a crozier.[5][11]

High on the south wall is a memorial to Bennet Langton, with Samuel Johnson's epitaph to his close friend.[5]

Music for the liturgy and the new organ

[edit]

The choir of St Michael's is Cantores Michaelis – choral scholars from the University of Southampton who are funded by The Friends of St Michael's. Cantores Michaelis sing every Sunday and feast days during the academic year. The group (founded in 2000 by the Director Keith Davis) specialises in unaccompanied repertoire composed for the Christian liturgy. The original organ was built by H. C. Sims in 1880. It was enlarged by J. W. Walker in 1950, and subsequently rebuilt in 1986 by Keith Scudamore. In 1995 Andrew Cooper, of Griffiths and Cooper, undertook further renovations of the instrument. These included replacing the action, restoring the console and making a few tonal improvements.[12][13] The pipe organ was replaced in December 2016 with a four manual replica of Hereford Cathedral's famous Willis organ, digitally sampled by Hauptwerk built and installed by Romsey Organ Works.

Bells

[edit]From the 17th century until 1878 there were six bells, which came from the Salisbury foundry. In 1878 two additional trebles were cast by John Warner & Sons. One of them was very thin and eventually needed to be repaired. In 1923 the peal was recast by Gillett & Johnston and hung in a new iron frame replacing the solid oak one.[14] Finally in 1947 two further bells were cast by John Taylor & Co from the bell metal salvaged from the ruins of Holyrood Church.[14][15] St. Michael's is one of only six towers in the Diocese of Winchester with ten bells.[16]

See also

[edit]- St. George's Episcopal Memorial Church, a church in the US with a stained glass window containing shards of glass collected from this church when it was damaged in World War II.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Coles, R.J. (1981). Southampton's Historic Buildings. City of Southampton Society. p. 7.

- ^ "Listed Buildings in Southampton" (PDF). Southampton City Council. p. 126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "St Michael's Church, Southampton". English Heritage. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ Rance, Adrian (1986). Southampton. An Illustrated History. Milestone. p. 31. ISBN 0-903852-95-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "St Michael's Church, Southampton". The Churches of Hampshire. Southern Life. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "St Michael's Church". Southampton Guide. schmap.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ a b "A Brief History of St Michael's Church". St Michaels's Church. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "Christ in Majesty". Hampshire Church Windows. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ "St. Michael defeating Satan". Hampshire Church Windows. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ a b Wadham, Anthony W. Building Stones of Southampton Four Geological Walks Around the City Centre. Southampton Geology Field Study Group. p. 50.

- ^ Wadham, Anthony W. Building Stones of Southampton Four Geological Walks Around the City Centre. Southampton Geology Field Study Group. p. 51.

- ^ "St Michael's Church: The organ". St Michaels's Church. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "Hampshire, Southampton—St. Michael, St. Michael's Square". National Pipe Organ Register. British Institute of Organ Studies. 1995. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ a b "St Michael's Church: The bells". St Michaels's Church. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "Southampton—S Michael Archangel". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. 23 January 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "Search result for towers in the Diocese of Winchester with 10 bells". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. 23 January 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.