Step aerobics

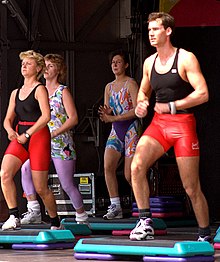

Step aerobics, also known as bench aerobics and step training,[1] is a form of aerobic exercise that involves stepping on and off a small platform.

Step aerobics was studied by physiologists in the 1980s, and in 1990 it swiftly grew in popularity in the U.S. as a style of health club exercise, largely because of promotion by Reebok of the Step Reebok device and associated exercise routines, prominently advocated by Gin Miller. Step aerobics attracted more men to group exercise classes.[2] At its peak in 1995, there were 11.4 million people doing step aerobics.[3]

Today, step aerobics classes are carried by many health clubs.[4] Exercise routines include weights held in the hands for upper body development. Music with a medium (not fast) tempo often accompanies the routine, and learning a choreography sequence can hold the participants' interest.

History

Background

Aerobics traces its origin to the 1968 book Aerobics by Dr. Kenneth H. Cooper, which inspired Jacki Sorensen to start her Aerobic Dancing program, combining music and dance routines to create an aerobic exercise pattern. Also in 1969, Judi Missett developed Jazzercise, combining jazz dance with fun exercise in much the same way. Building through the 1970s, Missett's Jazzercise and Sorensen's Aerobic Dancing became very popular in the U.S., such that by 1981–82 they counted 4,000 instructors each, and more than 300,000 students combined.[5][6]

In 1982, Jane Fonda's Workout video changed the fitness world dramatically, starting a boom in home video exercise instruction through the 1980s and beyond. This same boom benefited health clubs by increasing the number of people who were involved in fitness.[7][8]

Step development

Stair climbing exercise was already thousands of years old when physiologists started studying its medical characteristics in the 20th century. Climbing stairs was long known to be healthy exercise for the heart.[2] The act of stepping up and down on one bench was studied in 1986 by a team led by Doctor Fredric L. Goss of the Human Energy Research Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh. Goss et al examined the popular HeavyHands hand weights fitness product combined with stepping exercises on the "Superstep" 12-inch (30.5 cm) fitness bench, comparing this combination to treadmill exercises and finding them equivalent.[9] Goss followed this in 1988 with an evaluation of the energy expenditure of step aerobics combined with hand weights.[10]

At the same time, Atlanta-based aerobics competitor Gin Miller was sidelined from high-impact activities in 1986 when she injured her knee. She was advised by her physical therapist to build her strength back up by stepping on and off an upside-down plastic milk crate (11 inches (28 cm) tall).[11] The crate was too high, so she used her 8-inch front porch step instead. After a few weeks of therapy, she noticed her increased fitness and realized this would be a good workout method for others.[12] Working with Connie Collins Williams, Miller used prototypes made of plywood, and tried them out in an Atlanta Gold's Gym franchise, the location later called Sportslife. Working together, they developed 250 separate step-based movements. The program was aimed at men, the usual gym-goers at Gold's.[13] These wooden prototype benches were very long: 24 by 2 feet (7.32 by 0.61 m), with a choice of heights: 10, 11 and 12 inches. Small weights held in the hands could also be used.[14] Fitness instructor Kathy Smith first experienced the Williams/Miller prototype step aerobics program during its early days, thinking as she was leaving "This is the most cutting-edge workout I’ve ever seen."[15]

Miller and Williams formed a company called Bench Blast in late 1988, making wooden steps from 6 to 12 inches high.[12] They began to sell the benches and teach their style of step aerobics.[16] The two split in 1989, with Miller leaving for Reebok.[12][17] Miller's friend and Reebok shoe representative Kelly Watson saw the Bench Blast program, and recommended Miller visit Angel Martinez, Reebok's Director of Business Development.[14] Martinez thought the step aerobics idea was good, and introduced Miller to Reebok CEO Paul Fireman who quickly gave the go-ahead to hire Miller and start a major product campaign. Reebok already had connections with many health clubs through their shoe promotions, and they were very interested in any new aerobics program which would attract male customers, since existing classes were about 90% women.[18] Reebok commissioned physiology trials of the step exercise program, undertaken in 1989 by Doctors Lorna and Peter Francis at San Diego State University. The Francis study showed that 40 minutes of step aerobics was equivalent to running 7 miles (11 km) in terms of oxygen breathed and calories burnt, but the body stress was much lower, the same as normal walking.[2] Lorna Francis also observed a Bench Blast training session in May 1989, remarking that it was an excellent overall exercise regimen for people without joint problems.[19]

Meanwhile, in New Jersey, fitness trainer Cathe Friedrich had been working with long wooden benches which were 14 inches (36 cm) high. Up to six people at a time could perform her leg-strengthening and aerobics movements on one bench. In 1988 when she heard about the Bench Blast project,[20] she put together a video production company with Chris Williams, the owner of Four Seasons Health Spa in Glassboro, forming Step N Motion Videos.[21] They produced their first step aerobics video in mid-1989, using wooden benches.[21][22]

Problems with the Bench Blast wooden benches included difficulty of storage, sideways instability, slippery upper surface when wet with sweat, dangerous sharp corners, and the heights were too challenging.[23] Lyle Irwin, a shareholder of Sportslife gym, saw Williams and Miller struggling with these problems; he suggested the first adjustable-height step bench on June 19, 1989, with nesting stacked layers, and later patented the idea. Sportslife CEO Rich Boggs joined with Irwin to hire Industrial Design Associates (IDA) to fabricate an attractive plastic exercise aide in the form of an adjustable-height step. William J. Saunders and Samuel Crosby of IDA worked with QPI, a plastics molding company in Atlanta, to prepare a prototype step, which was first displayed in October 1989 in Chicago at a trade show. Reebok licensed "The Step" through Boggs and Irwin's new company, Sports Step. The step base unit was teal with a black non-skid upper surface. It came with two sets of risers in contrasting colors: purple and gray for health clubs, purple and pink for home users. The first official deliveries were in January 1990, carrying Reebok's name as well as The Step trademark.[24][25][23]

Early demonstration units were trialed by Step Reebok in select health clubs, including Mezzeplex in West Los Angeles in December 1989. Gin Miller taught the routines to local instructors.[26] Mezzeplex began offering two to three step aerobics classes every day.[27]

Demand for the Step Reebok device quickly rose, requiring Boggs to add two more manufacturing plants in other cities,[23] including one in Ontario, California.[28] Combined, the three plants were making 50,000 steps every month.[29] Sports Step extended their reach with manufacturing licenses in Japan and Europe.[28]

Two months after its introduction to the general public, step aerobics classes were attracting major media attention, starting with a March 1990 article published by The New York Times.[30] Miller promoted Step Reebok in person, touring the U.S. and demonstrating it at hundreds of exercise studios. Step aerobics became widely popular, helping the company sell many thousands of step devices, and millions of lightweight, flexible high-top shoes with ankle support.[28] For promoting aerobics through Step Reebok, Miller was named IDEA Fitness Instructor of the Year in 1991.[31] Step aerobics programs were soon developed by Jazzercise, Kathy Smith, Jane Fonda, Molly Fox, and New Zealand health club founder Les Mills. The year 1995 was the peak of step aerobics, with 11.4 million practitioners.[3]

Videos

The first home video of step aerobics was released during the weekend of July 28–30, 1989, by Cathe Friedrich who sold out her supply of tapes at the IDEA International Aerobics Convention in Nashville.[32] Also in town for the convention, Gin Miller appeared on Nashville's TV show Talk of the Town on July 28 to promote Bench Blast.[33] New Jersey fitness instructor Dawn Brown released Step It Out in 1990, one of the earliest adopters of Step Reebok. In 1991, more videos of step aerobics were released by Cher, Stacey Benson, Denise Austin, Victoria Johnson, Jenny Ford, Gilad Janklowicz, Debbie Tellshow, Cory Everson, Karen Flores, Carolyn Brown, and Esquire magazine featuring Marian Ramaikas.[34] A smaller device called Super Step was promoted with a video by Brenda Dykgraaf (later Dygraf) and Kathy Smith.[35]

Miller's Bench Blast colleague and co-developer Connie Collins Williams trademarked "BenchAerobix" in 1990, and at the same time put out a step aerobics video called BenchAerobix.[36] Williams trained instructors in her method, and promoted a smaller molded plastic bench, 36 by 14 inches (91 by 36 cm), with a fixed height of 8 inches for most students, and 10 inches for advanced levels.[13][17] She sold Bench Blast to Reebok in 1991,[37] to focus on BenchAerobix. Bench Blast trainer Sindy Benson[16] joined Reebok's 14-person training team.[38]

In March 1992, Reebok designed a new step with angular nesting legs.[24] They featured this new step in a moody industrial video led by Gin Miller, driven by live percussionists in a band. The video starts with a 1991 TV commercial showing a fit young couple running up the steps of the Guatemalan pyramid Tikal, intercut with scenes of people using the previous rounded step design in teal and purple. Then the Miller workout is performed on the new angular step design in dark and light gray.[39] A new Step Reebok logo was issued, with three horizontal lines representing the 'E' in Step.[40]

Characteristics

Step aerobics is one of several low-impact aerobic exercises, along with water aerobics, dance aerobics and fast walking.[41] Step aerobics is similar to climbing stairs, but performed while staying in one place. The step platform itself is much less expensive and more portable than a StairMaster, and needs no electricity to operate.[29]

Music for step aerobics should be medium tempo, typically 118 to 122 beats per minute (bpm). A rhythm of 126–128 bpm is sometimes used for advanced classes; Reebok defined 128 bpm as the "fastest permissible speed."[42] The style of music should emphasize the beat, for instance a steady four on the floor rather than offbeat syncopation. Choreography requires that the music present a predictable 32-beat, eight-measure sequence.[11][41] Playlists for aerobic dance may include such songs as "Strut" by the Cheetah Girls, "Carry Out" by Timbaland featuring Justin Timberlake, and "Every Teardrop Is a Waterfall" by Coldplay.[43]

Step and bench devices are usually molded polyethylene plastic, covered in rubber or other non-slip surface, with the lowest height starting at 4 inches (10 cm). This height can be increased in 2-inch (5 cm) increments to 8 inches (20 cm). Studies have been made of 10- and 12-inch benches, but these are not recommended for popular step aerobics classes.[35] The height of the step should be tailored to the individual; lower levels for beginners.[42][2] Typical steps have a length and width of 43 by 16 inches (109 by 41 cm). A smaller product called Super Step was 28 by 14 inches (71 by 36 cm). The step is never approached with the participant's back toward it.[44]

While women were already doing aerobic dance in the 1970s and 1980s, outnumbering men 9 to 1,[27] men were attracted to step aerobics in the 1990s because the style was simpler, not based on dance choreography with unfamiliar dance lingo.[23][45][46] Mixed-gender step classes were common from the start.[2] On the other hand, dance routines can be brought into step aerobics, for instance Phillip Weeden's "X-treme" hip-hop dance program with music by Beyoncé, Silentó and old school rappers.[47][48] Elements of step aerobics can be blended into other exercise styles such as kickboxing[49] or Zumba to create hybrid or combo styles.[50]

References

- ^ Pickett, Betty; Mosher, Patricia (November–December 1990). "Bench Aerobics". Strategies: A Journal for Physical and Sport Educators. 4 (2): 28–29. doi:10.1080/08924562.1990.10591769.

- ^ a b c d e Green, Penelope (September 2, 1990). "Beauty, the Next Step". The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Hua, Vanessa (April 22, 1999). "Firming Up Revenues". The Courant. Hartford, Connecticut.

- ^ "Back to the 1980s". Sports Fitness. November 14, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ McCormack, Patricia (October 16, 1981). "Womans' World: Aerobic Dancing: 'hips, hips' away!". United Press International. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Weiner, Yitzi (May 19, 2019). "Judi Sheppard Missett of Jazzercise". Authority Magazine. Medium.com. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Hendricks, Nancy (2018). Popular Fads and Crazes Through American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 526. ISBN 9781440851834.

- ^ Stillwell, Jadie (November 13, 2019). "That Time Jane Fonda Sculpted Abs to Save the Planet". Interview. Retrieved September 6, 2020. 1984 interview between Fonda and Maura Moynihan.

- ^ Goss, Fredric L. (November 20, 1987). "Are Treadmill Based Exercise Prescriptions Generalizable to Combined Arm and Leg Exercise?". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation. 7 (11): 551–555. doi:10.1097/00008483-198711200-00006.

- ^ Goss, Fredric L. (October 24, 1988). "Energy Cost of Bench Stepping and Pumping Light Handweights in Trained Subjects". Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 60 (4): 369–372. doi:10.1080/02701367.1989.10607465. PMID 2489865.

- ^ a b Karageorghis, Costas I. (2016). Applying Music in Exercise and Sport. Human Kinetics. p. 114. ISBN 9781492513810.

- ^ a b c Fisher, Laura (1991). "Step Right Up". American Health. Vol. 10, no. 7. pp. 66–70.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Barbara (September 25, 1990). "Approach the Bench: Step Training Is Here". The Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Hartford, Teresa (September 23, 2019). "Gin Miller… Meet the Creator of Step Aerobics". SGB Online. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Kathy. "Free 10-min Step Aerobics Video". Kathy Smith. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Kilgore, Vickie (June 13, 1989). "A step up on other aerobic exercises". Courier-Post. Camden, New Jersey. Gannett News Service.

- ^ a b Evertz, Mary (June 16, 1991). "Steps in the right direction". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Hartford, Teresa (September 23, 2019). "Step Reebok's Rise To Success… With Angel Martinez". SGB Online. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Kilgore, Vickie (May 28, 1989). "Bench: a workout and more (whew!)". The Tennessean. Nashville. p. E1.

- ^ Kremer, Wendy Niemi (1996). "Interview: Cathe Friedrich". Video Fitness. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Dove, Patricia (March 14, 2011). "Washington Township woman made quest to be healthy, active into full-time business venture". NJ. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Cathe Friedrich: 2011 NFHOF Inductee". National Fitness Hall of Fame. 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Cammy (October 25, 1990). "An exercise on the rise: step aerobics". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Step Co. v. Consumer Direct, Inc., 936 F. Supp. 960 (N.D. Ga. 1994)". Justia. September 29, 1994. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Condon, Garret (September 18, 1991). "One Step Makes Workouts More Strenuous". The Courant. Hartford, Connecticut.

- ^ "A Modal Robe for Barbra". Los Angeles Times. December 29, 1989. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Doheny, Kathleen (December 26, 1989). "Step Up in Class with New Exercise Program". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lim, Soon Neo (November 30, 1990). "Stair Climber Exercise Devices Becoming Stairway to Success". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Evertz, Mary (March 27, 1991). "The circuits are busy". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Lloyd, Barbara (March 26, 1990). "Step Up (and Down) to Sharper Workouts". The New York Times. p. C-10.

- ^ "IDEA Award Winners". IDEA Health & Fitness Association. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Download Step N Motion 1". Cathe. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "TV tapings, talks show guests this week". The Tennessean. July 23, 1989. p. 16.

- ^ Wallace, Judy (October 8, 1992). "Where to Step". The Palm Beach Post. p. 212. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Melillo, Wendy (June 11, 1991). "Step Up to the Beat with Bench Aerobics". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ BenchAerobix. 1990. OCLC 22864662. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Williams, Connie C. (2018). Empowering People to Pause. Media kit brochure from thepowertopause.com.

- ^ Simmons, Drew (November 11, 1992). "Fitness instructors step up the pace". The Jackson Hole Guide. p. C3.

- ^ Miller, Gin (1992). "Step Reebok: The Video". YouTube. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Step Reebok logo". Trademark Justia. April 10, 1992. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Hyde, Cheryl L.; American Association for Active Lifestyles and Fitness (2002). Fitness Instructor Training Guide. Kendall Hunt. pp. 85–108. ISBN 9780787292935.

- ^ a b Olson, Michele Scharff; Miller, Gin (June–July 1997). "Research in Action: Stepping To A New Beat". Gin Miller. Archived from the original on October 20, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2020. First published in the June–July 1997 issue of Reebok Alliance Newsletter.

- ^ Lawhorn, Chris (November 9, 2012). "Dance Cardio Music: Your Perfect Playlist". Shape. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Mazzeo, Karen S.; Mangili, Lauren M. (2012). Fitness! (5 ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 79–80, 103, 116. ISBN 9780840048097.

- ^ Dimon, Suzanne E. (August 20, 1990). "Do Real Men Do Aerobics?". The Daily Press. Newport News, Virginia. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Davidson; Van Horn, Patricia (March 19, 1992). "Low-impact workout draws men as well as women". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Zoldan, Rachel Jacoby (March 9, 2016). "Genius Trainer Combines Beyoncé and Step Aerobics for Best Dance Cardio Class Ever". Shape. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Peters, Terri (June 30, 2020). "This mom lost 75 pounds by taking a hip-hop step aerobics classes". Today. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Step Aerobics and Cardio Kickboxing Certification". American Sports and Fitness. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Caroline (2018). "A Brief History of Step Aerobics". GX United. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

External links

- 1992 Step Reebok video featuring Gin Miller, 58 minutes