Tarpan

| Tarpan Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Only known live photo of an alleged tarpan, which may have been a hybrid or feral animal, 1884 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †E. f. ferus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| †Equus ferus ferus Boddaert, 1785

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The tarpan (Equus ferus ferus), also known as Eurasian wild horse, was a subspecies of wild horse.[1] It is now extinct. The last individual believed to be of this subspecies died in captivity in the Russian Empire during 1909, although some sources claim that it was not a genuine wild horse due to its resemblance to domesticated horses.[2]

Beginning in the 1930s, several attempts were made to develop horses that looked like tarpans through selective breeding, called "breeding back" by advocates. The breeds that resulted included the Heck horse, the Hegardt or Stroebel's horse, and a derivation of the Konik breed, all of which have a primitive appearance, particularly in having the grullo coat color. Some of these horses are now commercially promoted as "tarpans". However, those who study the history of the ancient wild horse assert that the word "tarpan" describes only the true wild horse.

Name and etymology

The name "tarpan" or "tarpani" derives from a Turkic language (Kazakh or Kyrgyz) name meaning "wild horse".[3][4] The Tatars and the Cossacks distinguished the wild horse from the feral horse; the latter was called Takja or Muzin.[5][6]

In modern use, the term has been loosely used to refer to the predomesticated ancestor of the modern horse, Equus ferus, to the predomestic subspecies believed to have lived into the historic era, Equus ferus ferus, and to all European primitive or "wild" horses in general. The modern "bred-back" horse breeds are also promoted as "tarpan" by their supporters, though researchers discourage this use of the word, which they believe should only apply to the ancient E. ferus ferus.[citation needed]

Taxonomy

The tarpan was first described by Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin in 1771[7] ; he had seen the animals in 1769 in the district of Bobrov, near Voronezh. In 1784 Pieter Boddaert named the species Equus ferus, referring to Gmelin's description. Unaware of Boddaert's name, Otto Antonius published the name Equus gmelini in 1912, again referring to Gmelin's description. Since Antonius' name refers to the same description as Boddaert's it is a junior objective synonym. It is now thought that the domesticated horse, named Equus caballus by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, is descended from the tarpan; indeed, many taxonomists consider them to belong to the same species. By a strict application of the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, the tarpan ought to be named E. caballus, or if considered a subspecies, E. caballus ferus. However, biologists have generally ignored the letter of the rule and used E. ferus for the tarpan to avoid confusion with the domesticated subspecies.

It is debated if the small, free-roaming horses seen in the forests of Europe during 18th and 19th centuries and called "tarpan" were indeed wild, never-domesticated horses, hybrids of the Przewalski's horse and local domestic animals, or simply feral horses. Most studies have been based on only two preserved specimens and research to date has not positively linked the tarpan to Pleistocene or Holocene-era animals.[citation needed]

In 2003, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature "conserved the usage of 17 specific names based on wild species, which are predated by or contemporary with those based on domestic forms", confirming E. ferus for the tarpan. Taxonomists who consider the domestic horse a subspecies of the wild tarpan should use Equus ferus caballus; the name Equus caballus remains available for the domestic horse where it is considered to be a separate species.[8]

Appearance

Traditionally, two tarpan subtypes have been proposed, the forest tarpan and steppe tarpan, although there seem to be only minor differences in type. The general view is that there was only one subspecies, the tarpan, Equus ferus ferus.[2] The last individual, which died in captivity in 1909, was between 140 and 145 centimetres (55 and 57 in) tall at the shoulders, had a thick falling mane, a grullo coat colour, dark legs, and primitive markings, including a dorsal stripe and shoulder stripes.[2]

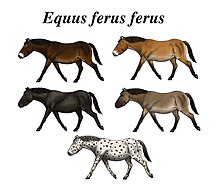

A number of genotypes have been identified within European wild horses from the Pleistocene and Holocene; their coat color genes including those creating bay, black and leopard complex are known to be present in the wild horse population in Europe and were depicted in cave paintings of wild horses during the Pleistocene.[10][10] The dun gene, a dilution gene seen in Przewalski's horse that also creates the grullo or "blue dun" coat, seen in the Konik has genetic markers identified in modern horses,[11] but has not yet been studied in European wild horses. It is considered likely that at least some wild horses had a dun coat.[10]

Some theorize that the tarpan had a standing mane because all other extant wild equines display this feature, and falling manes are considered an indication of domestication.[2] However, historical accounts do not unambiguously describe a standing mane in European wild horses, and it is likely that they had a short, falling mane. This feature is advantageous in regions with much rainfall because it diverts rain and snow from the neck and face and prevents a loss of heat, as much as a bushy tail. Mummified Siberian wild horses display a hanging mane as well.[12]

The appearance of European wild horses is reconstructed with genetic, osteologic and historic data. One genetic study suggests that bay was the predominant color in European wild horses.[13] During the Mesolithic, a gene coding a black coat color appeared on the Iberian peninsula. This color spread east but was less common than bay in the investigated sample and never reached Siberia.[13] Bay in combination with dun results in the "bay dun" color seen in Przewalski's horses, black with dun creates the grullo coat. A loss of dun dilution may have been advantageous in more forested western European landscapes, as dark colors were a better camouflage in forests.[12] Pangaré or "mealy" coloration, a characteristic of other wild equines, might have been present in at least some tarpans,[12] as historic accounts report a light-colored belly.[14] It is also likely that European wild horses had primitive markings, consisting of stripes on the shoulders, legs and spine.[10]

History

Wild horses have been present in Europe since the Pleistocene and ranged from southern France and Spain east to central Russia. There are cave drawings of primitive predomestication horses at Lascaux, France and in Cave of Altamira, Spain, as well as artifacts believed to show the species in southern Russia, where a horse of this type was domesticated around 3000 BCE.[15] Equus ferus had a continuous range from western Europe to Alaska; historic material suggests wild horses lived in most parts of Holocene Europe and the Eurasian steppe, except for parts of Scandinavia, Iceland and Ireland.[14]

The "forest horse" or "forest tarpan" was a hypothesis of various 19th-century natural scientists, including Tadeusz Vetulani, who suggested that the continuous forestation of Europe after the last ice age created forest-adapted subtype of the wild horse, which he named Equus sylvestris. However, historic references do not describe any major difference between the populations, therefore most authors assume there was only one subspecies of western Eurasian wild horse, Equus ferus ferus.[2] Nevertheless, a stocky type of horse living in forests and highlands was described during the 19th century in Spain, the Pyrenees, the Camargue, the Ardennes, Great Britain, and the southern Swedish upland. They had a robust head and strong body, and a long frizzy mane. The color was described as faint brown or yellowish brown with eel stripe and leg stripes, or wholly black legs. The flanks and shoulders were spotted, some of them tended to an ashy colour. They dwelled in rocky habitats and showed intelligent and fierce behaviour. In Dutch swamps, black wild horses were found with a large skull, small eyes and a bristly muzzle. The mane was full, with broad hooves and curly hair. However, it is possible that these were feral and not wild horses.[16]

Herodotus described lightly-coloured wild horses in an area now part of Ukraine in the 5th century BCE. In the 12th century, Albertus Magnus states that mouse-coloured wild horses with a dark eel stripe lived in the German territory, and in Denmark, large herds were hunted. Wild horses still were common in the east of Prussia during the 15th and early 16th centuries. During the 16th century, wild horses disappeared from most of the mainland of western Europe and became less common in eastern Europe as well. Belsazar Hacquet saw wild horses in the Polish zoo in Zamość during the Seven Years' War. According to him, those wild horses were of small body size, had a blackish brown colour, a large and thick head, short dark manes and tail hair, and a “beard”. They were absolutely untameable and defended themselves harshly against predators. Kajetan Kozmian visited the population at Zamość as well and reported that they were small and strong, had robust limbs and a constantly dark mouse colour. Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin witnessed herds in Voronezh in 1768. Those wild horses were described as very fast and shy and would flee by any noise, small with small pinned ears, and a short frizzly mane. The tail was shorter than in domestic horses. They were described as mouse-colored with a light belly and legs becoming black, although gray and white horses were mentioned as well. The coat was long and dense. Peter Simon Pallas witnessed possible wild tarpans in the same year in southern Russia. He thought they were feral animals that escaped during the confusions of wars. These herds were important game of the Tatars and numbered between five and 20 animals. The horses he described had a small body, large and thick heads, short frizzly manes and short tail hair, as well as pinned ears. The colour was described as faint brownish, sometimes brown or black. He also reported of obvious domestic hybrids with lightly colored legs or grays.[14]

The Natural History of Horses by 19th-century author Charles Hamilton Smith also described tarpans. According to Smith, the herds of wild horses numbered from a few to hundred individuals. They often were mixed with domestic horses, and alongside pure herds there were herds of feral horses or hybrids. The color of pure tarpans was described as constantly brown, cream-colored or mouse-colored. The short frizzy mane was reported to be black, as were the tail and legs. The ears either were of varying size, but set up high at the skull. The eyes were small. According to Smith, tarpans made stronger sounds than domestic horses and the overall appearance of these wild horses was mule-like.[16] A tarpan herd survived in the Zoo of Zamość until 1806, when the reserve had to sell them because of economic problems. They were dispersed onto the local farms at the Biłgoraj region, tamed and bred to domestic horses. According to Kozmian, wild horses had been exterminated in the Polish wilderness shortly before, because they damaged hay collected for livestock.[14]

Extinction

The human-caused extinction of the tarpan began in Southern Europe, possibly in antiquity.[14] While humans had been hunting wild horses since the Paleolithic,[12] during historic times horse meat was an important source of protein for many cultures. As large herbivores, the range of the tarpan was continuously decreased by the increasing civilization of the Eurasian continent. Wild horses were further persecuted because they caused damage to hay storages and often took domestic mares from pastures. Furthermore, interbreeding with wild horses was an economic loss for farmers since the foals of such matings were intractable.[14] Tarpans survived the longest in the southern parts of the Russian steppe. By 1880, when most "tarpans" may have become hybrids, wild horses became very rare. In 1879 the last scientifically confirmed individual was killed. After that, only dubious sightings were documented.[14] As the tarpan horse died out in the wild between 1875 and 1890, the last considered-wild mare was accidentally killed during an attempt at capture. The last captive tarpan died in 1909 in a Russian zoo.[18]

An early 19th-century attempt was made by the Polish government to save the tarpan type by establishing a preserve for animals descended from the tarpan in a forested area in Białowieża.[15] In 1780, a wildlife park was established protecting a population of tarpans until the beginning of the 19th century. When the preserve had to close down in 1806, the last remaining tarpans were donated to local farmers and it is claimed that they survived through crossbreeding with domestic horses.[2][19] The Konik is claimed to descend from these hybrid horses.[15] Recent research has highlighted a significant degree of anatomic difference between free-roaming Konik in the Netherlands and the modern domesticated horse.[20]

Interbreeding with domestic horses

The oldest archaeological evidence for domesticated horses is from Kazakhstan and Ukraine between 6000 and 5500 years BP (Before Present).[21] The diverse mitochondrial DNA of the domestic horse coinciding with the very low diversity on the Y chromosome suggests that many mares but only very few stallions were used,[22] and local use of wild mares or even secondary sites of domestication are likely.[23] Therefore, the European tarpan may have contributed to the domestic horse.[23]

Some researchers consider the tarpans of the last two centuries of their existence to be mixed wild and feral population or completely feral horses. Few consider the more recent animals historically called "tarpans" to be genuine wild horses without domestic influence.[14] Historic references to "wild horses" may actually refer to feral domestic horses or hybrids. Some 19th-century authors wrote that local "wild" horses had hoof problems, leading to crippled legs, and therefore they assumed these were feral horses.[14] Other contemporary authors claimed all "wild" horses between the Volga River and the Ural were actually feral. However, others thought that this was too speculative and assumed that wild, undomesticated horses still lived into the 19th century.[16] Domestic horses used in warfare often were turned loose when they were not needed. Also, remaining wild stallions could steal domestic mares. There are some accounts from the 18th and 19th centuries of wild herds with typical wild horse features such as large heads, pinned ears, short frizzy mane and tail, but mentioned animals with domestic influence as well.[14]

The only known individual to be photographed was the so-called Cherson-tarpan, which was caught as a foal near Novovorontsovka in 1866. It died in 1887 in the Moscow Zoo. The nature of this horse was dubious in its lifetime, because it showed almost none of the wild horse features described in the historic sources.[2] Today it is assumed this individual either was a hybrid or a feral domestic horse.[14]

Three attempts have been made to use selective breeding to create a type of horse that resembles the tarpan phenotype, though recreating an extinct subspecies is not genetically possible with current technology. In 1936, Polish university professor Tadeusz Vetulani selected Polish farm horses that he believed resembled the historic tarpan and started a selective breeding program. This horse breed is now called the Konik, which clusters genetically with other domestic horse breeds, including those as diverse as the Mongolian horse and the Thoroughbred.[23] In the early 1930s, Berlin Zoo Director Lutz Heck and Heinz Heck of the Munich Zoo began a program crossbreeding Koniks with Przewalski horses, Gotland Ponies, and Icelandic horses. By the 1960s they produced the Heck horse.[24] In the mid-1960s, Harry Hegard started a similar program in the United States using Mustangs and local working ranch horses that has resulted in the Hegardt or Stroebel's Horse.[25]

While all three breeds have a primitive look that resembles the wild type tarpan in some respects, they are not genetically tarpans and the wild, predomestic European horse remains extinct. However, this does not prevent some modern breeders from marketing horses with these features as a "tarpan".[26] In spite of sharing primitive external features, the Konik and Hucul horses have markedly different conformation with differently-proportioned body measurements, thought in part to be linked to living in different habitats.[2][27] Other breeds sometimes alleged to be surviving tarpans include the Exmoor pony and the Dülmen pony. However, genetic studies do not set any of these breeds apart from other domestic horses.[23][28] On the other hand, there has not yet been a study comparing domestic breeds directly with the European wild horse.[29]

See also

References

- ^ Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 630-631. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bunzel-Drüke, Finck, Kämmer, Luick, Reisinger, Riecken, Riedl, Scharf & Zimball: "Wilde Weiden: Praxisleitfaden für Ganzjahresbeweidung in Naturschutz und Landschaftsentwicklung

- ^ "Tarpan". Merriam-Webster Unabridged.

- ^ "Tarpan". Vasmer's Etymological Dictionary.

- ^ Boyd, Lee; Houpt, Katherine A. (1994). Przewalski's Horse: The History and Biology of an Endangered Species. SUNY Series in Endangered Species. Albany State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1890-1.

- ^ Smith, Charles Hamilton (1841–1866). The Natural History of Horses, with Memoir of Gesner.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Comparative craniometry of "Shatilov's tarpan" (Equus gmelini Antonius, 1912): a problem of species status" (PDF). Zoological Museum of Moscow University. 49. 2008.

- ^ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (2003). Opinion 2027 (Case 3010). "Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are predated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved." Bulletin of Zoologic Nomenclature, 60:81-84.

- ^ Bennett, 1998

- ^ a b c d Pruvost et al. (2011): Genotypes of predomestic horses match genotypes painted in Paleolithic works of cave art. (PDF)

- ^ "Horse Dun Zygosity Test". Vgl.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Sue, 2008: Exmoor Ponies: Survival of the Fittest – A natural history.

- ^ a b Ludwig et al. 2009: Coat color variation at the beginning of horse domestication

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tadeusz Jezierski, Zbigniew Jaworski: Das Polnische Konik. Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei Bd. 658, Westarp Wissenschaften, Hohenwarsleben 2008

- ^ a b c "Tarpan". Breeds of Livestock. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ a b c Smith, Charles Hamilton (1814/1866). The Natural history of Horses, with Memoir of Gesner.

- ^ http://www.pnas.org/content/108/46/18626.full.pdf

- ^ Dohner, Janet Vorwald (2001). "Equines: Natural History". In Dohner, Janet Vorwald (ed.). Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Topeka, KS: Yale University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-300-08880-9.

- ^ Thomas Jansen: Untersuchungen zur Phylogenie und Domestikation des Hauspferdes (Equus ferus f. caballus) Stammesentwicklung und geografische Verteilung. 2002 (PDF Archived 2016-03-08 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ May-Davis, Sharon; Brown, Wendy; Shorter, Kathleen; Vermeulen, Zefanja; Butler, Raquel; Koekkoek, Marianne; May-Davis, Sharon; Brown, Wendy Y.; Shorter, Kathleen (2018-02-01). "A Novel Non-Invasive Selection Criterion for the Preservation of Primitive Dutch Konik Horses". Animals. 8 (2): 21. doi:10.3390/ani8020021. PMC 5836029. PMID 29389896.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Outram, A.K., Stear, N.A., Bendrey, R., Olsen, S., Kasparov, A., Zaibert, V., Thorpe, N. and Evershed, R.P. 2009 The Earliest Horse Harnessing and Milking Science. 323(5919): 1332–1335

- ^ Lindgren et al. 2004: Limited number of patrilines in horse domestication

- ^ a b c d Jansen et al. 2002: Mitochondrial DNA and the origins of the domestic horse

- ^ Heck, H. (1952). "The Breeding-Back of the Tarpan". Oryx. 1 (7): 338. doi:10.1017/S0030605300037662.

- ^ The Extinction Website. "Equus ferus ferus". Recently Extinct Animals. The Extinction Website. Archived from the original on 2009-01-13. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ "North American Tarpan Association". Tarpanassociation.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ^ Komosa, M.; Purzyc, H. (2009). "Konik and Hucul horses: A comparative study of exterior measurements". Journal of Animal Science. 87 (7): 2245–2254. doi:10.2527/jas.2008-1501. PMID 19329479.

- ^ Cieslak et al. 2010: Origin and History of Mitochondrial DNA lineages in domestic horses

- ^ Jordana & Sanchez, 1995: Analysis of genetic relationships in horse breeds