The Man Who Laughs

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

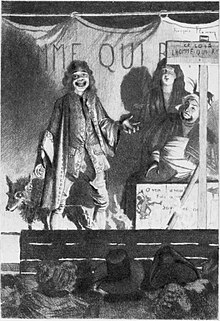

"At the Green Box.", Frontispiece to volume II of the 1869 English translation. | |

| Author | Victor Hugo |

|---|---|

| Original title | L'Homme qui rit |

| Cover artist | François Flameng |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Novel |

| Published | April 1869 A. Lacroix, Verboeckhoven & Ce |

| Publication place | France |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 386 |

| OCLC | 49383068 |

The Man Who Laughs (also published under the title By Order of the King) is a novel by Victor Hugo, originally published in April 1869 under the French title L'Homme qui rit. It was adapted into a popular 1928 film, directed by Paul Leni and starring Conrad Veidt, Mary Philbin and Olga Baclanova.

It was recently adapted for the 2012 French film L'Homme Qui Rit, directed by Jean-Pierre Améris and starring Gérard Depardieu, Marc-André Grondin and Christa Theret. In 2016, it was adapted as The Grinning Man, an English musical. In 2018, The Man Who Laughs is set to be adapted into a South Korean musical of the same name starring EXO's Suho, Park Hyo-shin and Park Kang Hyun.

Background

Hugo wrote The Man Who Laughs, or the Laughing Man, over a period of fifteen months while he was living in the Channel Islands, having been exiled from his native France because of the controversial political content of his previous novels. Hugo's working title for this book was On the King's Command, but a friend suggested The Man Who Moans Loudly.[citation needed]

Plot

In late 17th-century England, a homeless boy named Gwynplaine rescues an infant girl during a snowstorm, her mother having frozen to death whilst feeding her. They meet an itinerant carnival vendor who calls himself Ursus, and his pet wolf, Homo. Gwynplaine's mouth has been mutilated into a perpetual grin; Ursus is initially horrified, then moved to pity, and he takes them in. Fifteen years later, Gwynplaine has grown into a strong young man, attractive except for his distorted visage. The girl, now named Dea, is blind, and has grown into a beautiful and innocent young woman. By touching his face, Dea concludes that Gwynplaine is perpetually happy. They fall in love. Ursus and his surrogate children earn a meagre living in the fairs of southern England. Gwynplaine keeps the lower half of his face concealed. In each town, Gwynplaine gives a stage performance in which the crowds are provoked to laughter when Gwynplaine reveals his grotesque face.

The spoiled and jaded Duchess Josiana, the illegitimate daughter of King James II, is bored by the dull routine of court. Her fiancé, David Dirry-Moir, to whom she has been engaged since infancy, tells the Duchess that the only cure for her boredom is Gwynplaine. Josiana attends one of Gwynplaine's performances, and is aroused by the combination of his virile grace and his facial deformity. Gwynplaine is aroused by Josiana's physical beauty and haughty demeanor. Later, an agent of the royal court, Barkilphedro, who wishes to humiliate and destroy Josiana by compelling her to marry the 'clown' Gwynplaine, arrives at the caravan and compels Gwynplaine to follow him. Gwynplaine is ushered to a dungeon in London, where a physician named Hardquannone is being tortured to death. Hardquannone recognizes Gwynplaine, and identifies him as the boy whose abduction and disfigurement Hardquannone arranged twenty-three years earlier. A flashback relates the doctor's story.

During the reign of the despotic King James II, in 1685–1688, one of the King's enemies was Lord Linnaeus Clancharlie, Marquis of Corleone, who had fled to Switzerland. Upon the baron's death, the King arranged the abduction of his two-year-old son and legitimate heir, Fermain. The King sold Fermain to a band of wanderers called "Comprachicos": criminals who mutilate and disfigure children, who are then forced to beg for alms or who are exhibited as carnival freaks.

Confirming the story is a message in a bottle recently brought to Queen Anne. The message is a final confession from the Comprachicos, written in the certainty that their ship was about to founder in a storm. The message explains how they renamed the boy "Gwynplaine", and abandoned him in a snowstorm before setting to sea. David Dirry-Moir is the illegitimate son of Lord Linnaeus. Now that Fermain is known to be alive, the inheritance promised to David on the condition of his marriage to Josiana will instead go to Fermain.

Dea is saddened by Gwynplaine's protracted absence. Barkilphedro lies to Ursus that Gwynplaine is dead. The frail Dea becomes ill with grief. The authorities condemn them to exile for illegally using a wolf in their shows.

Josiana has Gwynplaine secretly brought to her so that she may seduce him. She is interrupted by the delivery of a pronouncement from the Queen, informing Josiana that David has been disinherited, and the Duchess is now commanded to marry Gwynplaine. Josiana rejects Gwynplaine as a lover, but dutifully agrees to marry him.

Gwynplaine is instated as Lord Fermain Clancharlie, Marquis of Corleone, and permitted to sit in the House of Lords. When he addresses the peerage with a fiery speech against the gross inequality of the age, the other lords are provoked to laughter by Gwynplaine's clownish grin. David defends him and challenges a dozen Lords to duels, but he also challenges Gwynplaine; the new Marquis' speech inadvertently condemned David's mother, who abandoned David's father to become the mistress of Charles II.

Gwynplaine renounces his peerage and travels to find Ursus and Dea. He is nearly driven to suicide when he is unable to find them. Learning that they are to be deported, he locates their ship and reunites with them. Dea is ecstatic, but abruptly dies. Ursus faints. Gwynplaine, as though in a trance, walks across the deck while speaking to the dead Dea, and throws himself overboard. When Ursus recovers, he finds Homo sitting at the ship's rail, howling at the sea.

Adaptations

Film

See The Man Who Laughs (film) for the full list of film adaptations.

Theatre

This section is written like a review. (March 2016) |

- Clair de Lune, a stage play written by Blanche Oelrichs under her male pseudonym Michael Strange, which ran for 64 performances on Broadway from April to June 1921. Oelrichs/Strange made some extremely arbitrary changes to the story, such as altering the protagonist's name to “Gwymplane”. The play features some very contrived and stilted dialogue, and would probably never have been produced if not for the fact that Oelrichs's husband at this time was the famed actor John Barrymore, who agreed to play Gwymplane and persuaded his sister Ethel Barrymore to portray Queen Anne. The ill-starred drama was dismissed as a vanity production, indulged by Barrymore purely to give his wife some credibility as playwright “Michael Strange”. The review by theatre critic James Whittaker of the Chicago Tribune was headlined “For the Love of Mike!”

- In 2005, The Stolen Chair Theatre Company recreated the story as a "Silent film for the stage." This adaptation pulled equally from Hugo's novel, the 1927 Hollywood Silent film, and from the creative minds of Stolen Chair. Stolen Chair's collectively created adaptation was staged as a live silent film, with stylized movement, original musical accompaniment, and projected intertitles. Gwynplaine was brought to life by Jon Campbell and was joined by Jennifer Wren, Alexia Vernon, Dennis Wit and Cameron J. Oro. It played in New York to critical acclaim and was published in the book, Playing with Cannons. It was revived in 2013 by the same company.

- In 2006 the original story was adapted into a musical by Alexandr Tyumencev (composer) and Tatyana Ziryanova (Russian lyrics),[1] entitled 'The Man Who Laughs' ('Человек, который смеётся'). This musical adaptation was performed by the Seventh Morning Musical Theatre, opening November 6, 2006.[2]

- In 2013, another musical version surfaced in Hampton Roads, VA featuring a blend of Jewish, Gypsy and Russian song styles.

- In 2016 a musical adaptation titled The Grinning Man opened at the Bristol Old Vic, followed by a transfer to the Trafalgar Studios in London's West End from December 2017.

- In 2018, a South Korean musical adaptation of the same title, i.e., The Man Who Laughs , starring Park Hyo Shin (Veteran Singer and Musical actor), EXO's Suho, Park Kang Hyun ((Hangul: 박강현) a promising rookie musical actor who made his debut in 2015 and played in several musicals including In the Heights as Benny, Evil Dead as Ash, Kinky boots as Charlie, etc. Also he starred as Fraser in the stage play Our bad Magnet and appeared in a classical crossover singing competition Phantom Singer on JTBC and won second place as a member of Miraclass )is set to run from July 10 to August 26 at the Seoul Arts Centre's Opera House and from September 4 to October 28 at the Seoul Bluesquare Interpark Hall.

Comics

- The Man Who Laughs has been cited as an inspiration for the DC Comics super-villain known as the Joker.

- In May 1950, the Gilberton publishing company produced a comic-book adaptation of The Man Who Laughs as part of their prestigious Classics Illustrated series. This adaptation featured artwork by Alex A. Blum, much of it closely resembling the 1928 film (including the anachronistic Ferris wheel). The character of Gwynplaine is drawn as a handsome young man, quite normal except for two prominent creases at the sides of his mouth. As this comic book was intended for juvenile readers, there may have been an intentional editorial decision to minimise the appearance of Gwynplaine's disfigurement. A revised Classics Illustrated edition, with a more faithful script by Al Sundel, and a painted cover and new interior art by Norman Nodel, was issued in the spring of 1962. Nodel's artwork showed a Gwynplaine far more disfigured than the character's appearance in either the 1928 film or the 1950 Classics edition.

- A second comic book version was produced by artist Fernando de Felipe, published by S. I. ARTISTS and republished by Heavy Metal Magazine in 1994. This adaptation was intended for a mature audience and places more emphasis on the horrific elements of the story. De Felipe has simplified and taken some liberties with Hugo's storyline. His rendering emphasizes the grotesque in Hugo and excludes the elements of the sublime that are equally important in the original.

- A third comic book version of the story was published in 2013, featuring notable writer David Hine and artist Mark Stafford.

Criticism

Hugo's Romantic novel The Man Who Laughs places its narrative in 17th-century England, where the relationships between the bourgeoisie and aristocracy are complicated by continual distancing from the lower class. Hugo's protagonist, Gwynplaine (a physically transgressive figure, something of a monster), transgresses these societal spheres by being reinstated from the lower class into the aristocracy — a movement which enabled Hugo to critique construction of social identity based upon class status. Stallybrass and White's "The Sewer, the Gaze and the Contaminating Touch" addresses several of the class theories regarding narrative figures transgressing class boundaries. Gwynplaine specifically can be seen to be the supreme embodiment of Stallybrass and White's "rat" analysis, meaning Hugo's protagonist is, in essence, a sliding signifier.[3]

See also

References

- ^ Человек, который смеется [Театр мюзикла "Седьмое утро"] ... [The Man Who Laughs [Seventh Day Musical Theater] ...]. Torrentino (in Russian). Retrieved 29 December 2017.

Либретто: Татьяна Зырянова / Музыка: Александр Тюменцев / Режиссер: Татьяна Зырянова (Libretto: Tatyana Ziryanova / Music: Alexander Tyumencev / Producer: Tatyana Ziryanova

{{cite web}}: Invalid|script-title=: missing prefix (help) - ^ Спектакль Человек, который смеется [Performance of The Man Who Smiles]. Ваш Досуг (Your Leisure Time) (in Russian). ООО РДВ-Медиа (RDV-Media LLC). September 13, 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Politics and Poetics of Transgression. Routledge. July 1986. ISBN 0416415806.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help)

External links

- The Man Who Laughs at Project Gutenberg

The Man Who Laughs public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Man Who Laughs public domain audiobook at LibriVox