The Secret of the Unicorn

| The Secret of the Unicorn (Le Secret de La Licorne) | |

|---|---|

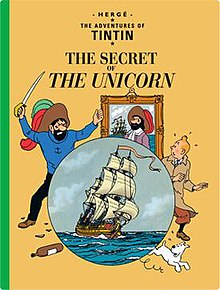

Cover of the English edition | |

| Date | 1943 |

| Series | The Adventures of Tintin |

| Publisher | Casterman |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Hergé |

| Original publication | |

| Published in | Le Soir |

| Date of publication | 11 June 1942 – 14 January 1943 |

| Language | French |

| Translation | |

| Publisher | Methuen |

| Date | 1959 |

| Translator |

|

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | The Shooting Star (1942) |

| Followed by | Red Rackham's Treasure (1944) |

The Secret of the Unicorn (Template:Lang-fr) is the eleventh volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised daily in Le Soir, Belgium's leading francophone newspaper, from June 1942 to January 1943 amidst the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. The story revolves around young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy, and his friend Captain Haddock, who discover a riddle left by Haddock's ancestor, the 17th century Sir Francis Haddock, which could lead them to the hidden treasure of the pirate Red Rackham. To unravel the riddle, Tintin and Haddock must obtain three identical models of Sir Francis's ship, the Unicorn, but they discover that criminals are also after these model ships and are willing to kill in order to obtain them.

The Secret of the Unicorn was a commercial success and was published in book form by Casterman shortly after its conclusion. Hergé concluded the arc begun in this story with Red Rackham's Treasure, while the series itself became a defining part of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. The Secret of the Unicorn remained Hergé's favourite of his own works until creating Tintin in Tibet (1960). The story was adapted for the 1957 Belvision animated series, Hergé's Adventures of Tintin, for the 1991 animated series The Adventures of Tintin by Ellipse and Nelvana, and for the feature film The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn (2011), directed by Steven Spielberg.

Synopsis

While browsing on the Brussels Voddenmarket/Marché aux puces at the Vossenplein in the Marollen, Tintin purchases an antique model ship which he intends to give Captain Haddock. Two strangers, model ship collector Ivan Ivanovitch Sakharine and antique-scout Barnaby, independently try to persuade Tintin to sell the model to them. He also sees the two police detectives, Thomson and Thompson, on the look out for a pickpocket. At Tintin's flat, Snowy accidentally knocks the model over and breaks its mainmast. Having repaired it, and shown the ship to Haddock, Tintin discovers that the ship is named the Unicorn, after a ship commanded by Haddock's ancestor. While Tintin is out, the ship is stolen from his apartment; in the investigation, he discovers that Sakharine owns an identical model, also named the Unicorn. At home, Tintin discovers a miniature scroll, and realises that this must have been hidden in the mast of the model which Snowy had broken. Written on the parchment is a riddle: "Three brothers joyned. Three Unicorns in company sailing in the noonday sunne will speak. For 'tis from the light that light will dawn, and then shines forth the Eagle's cross".[1]

Upon hearing of the riddle, Captain Haddock explains that the Unicorn was a 17th-century warship captained by his ancestor, Sir Francis Haddock, but seized by a pirate band led by Red Rackham. Alone of his crew to survive the capture, Sir Francis killed Rackham in single combat and destroyed the Unicorn; but later built three models, which he left to his sons. Meanwhile, Barnaby requests a meeting with Tintin, but is gunned down on Tintin's doorstep before he can speak, and points to sparrows as a cryptic clue to the identity of his assailant. Later, Tintin is kidnapped by the perpetrators of the shooting: the Bird brothers, two unscrupulous antique dealers who own the third model of the Unicorn, and who now seek the treasure plundered by Rackham. Tintin escapes from the cellars of the Bird brothers' country estate, Marlinspike Hall, while the Captain arrives with officers Thomson and Thompson to arrest them. It is found that the Bird Brothers have only one of the parchments, as two were lost when their wallet was stolen. It is also revealed that Barnaby survived the Bird brothers' shooting him on Tintin's doorstep, and has made a full recovery, much to Max Bird's enragement. The Bird brothers are arrested. Tintin and Thomson and Thompson track down the pickpocket, Aristides Silk, a kleptomaniac who has a penchant for collecting wallets, and obtain the Bird Brothers' wallet, containing the missing two parchments. By combining the three parchments and holding them to the light, Tintin and Haddock discover the coordinates (20°37'42.0" N 70°52'15.0" W) of the lost treasure and plan an expedition to find it.[2]

History

Background

Amidst the German occupation of Belgium during World War II, Hergé had accepted a position working for Le Soir, Belgian's largest Francophone daily newspaper. Confiscated from its original owners, the German authorities permitted Le Soir to reopen under the directorship of Belgian editor Raymond de Becker, although it remained firmly under Nazi control, supporting the German war effort and espousing anti-Semitism.[3] After joining Le Soir on 15 October 1940, Hergé became editor of its new children's supplement [Le Soir Jeunesse] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), with assistance by old friend Paul Jamin and cartoonist Jacques Van Melkebeke, before paper shortages forced Tintin to be serialised daily in the main pages of Le Soir.[4] Some Belgians were upset that Hergé was willing to work for a newspaper controlled by the occupying Nazi administration,[5] although he was heavily enticed by the size of Le Soir's readership, which reached 600,000.[6] Faced with the reality of Nazi oversight, Hergé abandoned the overt political themes that had pervaded much of his earlier work, instead adopting a policy of neutrality.[7] Without the need to satirise political types, entertainment producer and author Harry Thompson observed that "Hergé was now concentrating more on plot and on developing a new style of character comedy. The public reacted positively."[8]

The Secret of the Unicorn was the first of The Adventures of Tintin which Hergé had collaborated on with Van Melkebeke to a significant degree; biographer Benoît Peeters suggested that Van Melkebeke should rightly be considered the story's "co-scriptwriter".[9] It was Hergé's discussions with Van Melkebeke that led him to craft a more complex story than he had in prior Adventures.[10] Van Melkebeke had been strongly influenced by the adventure novels of writers like Jules Verne and Paul d'Ivoi, with this influence being apparent throughout the story.[9] The inclusion of three hidden scrolls has parallels with Verne's 1867 story, The Children of Captain Grant, which Van Melkebeke had recommended to Hergé.[11] Hergé acknowledged Van Melkebeke's contribution by including a cameo of him within the market scene at the start of the story; this was particularly apt as Van Melkebeke had purchased his books in Brussels' Old Market as a child.[12]

The Secret of the Unicorn was the first half of a two-part story arc that was concluded in the following adventure, Red Rackham's Treasure. This arc was the first that Hergé had utilised since Cigars of the Pharaoh and The Blue Lotus (1934–36).[13] However, as Tintin expert Michael Farr related, whereas Cigars of the Pharaoh and The Blue Lotus had been largely "self-sufficient and self-contained", the connection between The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure would be far closer.[14]

In previous works, Hergé had drawn upon a variety of pictorial sources, such as newspaper clippings, from which to draw the scenes and characters; for The Secret of the Unicorn he drew upon an unprecedented variety of these sources.[15] In drawing many of the old vessels, Hergé initially consulted the then recently published L'Art et la Mer ("Art and the Sea") by Alexandre Berqueman.[16] Seeking further accurate depictions of old naval vessels, Hergé consulted a friend of his, Gérard Liger-Belair, who owned a Brussels shop specialising in model ships. Liger-Belair produced plans of a 17th-century French fifty-gun warship for Hergé to copy; Le Brillant, which had been constructed in Le Havre in 1690 by the shipwright Salicon and then decorated by Jean Bérain the Elder.[17]

He also studied other vessels from the period, such as the Le Soleil Royal, La Couronne, La Royale and Le Reale de France, to better understand 17th-century ship design. It was from the Le Reale de France that he gained a basis for his design of the Unicorn's jolly boat.[18] No ship named the Unicorn was listed in the annals of the French Navy, but Hergé instead took the name from a British frigate which had been active in the mid-18th century; the fictional ship's unicorn figurehead was also adopted from the frigate.[18]

The character of Red Rackham was partly inspired by Jean Rackam, a fictional pirate who appeared in a story alongside female pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read that Hergé encountered in a November 1938 edition of Dimanche-Illustré.[19] Red Rackham's looks and costumes were also inspired by the character, Lerouge, who appears in C. S. Forester's novel, The Captain from Connecticut, and by the 17th-century French buccaneer Daniel Montbars.[20] The name of Marlinspike Hall—Moulinsart in French—was based upon the name of the real Belgian town, Sart-Moulin.[21] The actual design of the building was based upon the Château de Cheverny, albeit with the two outer wings removed.[22] In introducing Francis Haddock to the story, Hergé made Captain Haddock the only character in the series (except Jolyon Wagg, introduced later) to have a family and an ancestry.[23] The Secret of the Unicorn was set entirely in Belgium and was the last Adventure to be set there until The Castafiore Emerald.[24] It would also be Hergé's favourite story until Tintin in Tibet.[25]

Historical parallels

After publishing the book, Hergé learned that there had actually been an Admiral Haddock who had served in the British Royal Navy during the late 17th and early 18th centuries: Sir Richard Haddock (1629–1715). Richard Haddock was in charge of the Royal James, the flagship of the Earl of Sandwich during the Battle of Solebay of 1672, the first naval battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War. During the fighting, the Royal James was set alight and Haddock escaped but had to be rescued from the sea, following which his bravery was recognised by the British monarch, King Charles II. He subsequently took command of another ship, the Royal Charles, before becoming a naval administrator in later life.[26] Admiral Haddock's grandfather, also named Richard, commanded the ship of the line HMS Unicorn during the reign of King Charles I.[27]

Another individual known as Captain Haddock had lived in this period, who had commanded a fire ship, the Anne and Christopher. It was recorded by David Ogg that this captain and his ship had been separated from their squadron whilst out at sea and so docked at Málaga to purchase goods that could be taken back to Britain and sold for a profit. For this action, Haddock was brought before an admiralty tribunal in 1674, where he was ordered to forfeit all profits from the transaction and suspended from his command for six months.[26]

Publication

Le Secret de La Licorne began serialisation as a daily strip in newspaper Le Soir from 11 June 1942.[28] As with previous adventures, it then began serialisation in the French Catholic newspaper Cœurs Vaillants, from 19 March 1944.[28] In Belgium, it was then published in a 62-page book format by Editions Casterman in 1943.[28] Now fully coloured,[29] the book included a new cover design created by Hergé after he had completed the original serialisation of the story,[30] along with six large colour drawings.[31] The first printing sold 30,000 copies in Francophone Belgium.[32]

The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure were the first two Adventures of Tintin to be published in English-language translations for the British market. Published by Casterman, these two editions sold poorly and have since become rare collector's items.[33] Both stories would be republished for the British market seven years later, this time by Methuen with new translations provided by Michael Turner and Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper.[34] In the English translation, Sir Francis Haddock was described as serving the British monarch Charles II, in contrast to the original French version, in which he serves French king Louis XIV.[35]

The series' Danish publishers, Carlsen, later located a model of an early-17th-century Danish ship called the Enhjørnigen (The Unicorn) which they gave to Hergé. Constructed in 1605, Enhjørnigen had been wrecked in an attempt to navigate the Northwest Passage.[36]

Critical analysis

The Secret of the Unicorn resembled the earlier Adventures of Tintin in its use of style, colour and content, leading Harry Thompson to remark that it "unquestionably" belongs to the 1930s, considering it to be "the last and best of Hergé's detective mysteries."[24] He asserted that this story and Red Rackham's Treasure marked the third and central stage of "Tintin's career", also stating that here, Tintin has been converted from a reporter into an explorer to cope with the new political climate.[13] He further added his opinion that it was "the most successful of all Tintin's adventures".[24] Jean-Marc Lofficier and Randy Lofficier asserted that Sir Francis Haddock was "the best realised character" in the story, conversely describing the Bird Brothers as "relatively uninspired villains".[37] They went on to state that The Secret of the Unicorn-Red Rackham's Treasure arc represents "a turning point" for the series as it shifts the reader's attention from Tintin to Haddock, who has become "by far, the most interesting character".[37] They praised the "truly outstanding storytelling" of The Secret of the Unicorn, ultimately awarding it a rating of four out of five.[38]

Phillipe Goddin commented on the scene in the story in which Haddock relates the life of his ancestor, stating that the reader is "alternately projected into the present and the past with staggering mastery. Periods interlocked, enriched one another, were amplified and married in a stunning fluidity. Hergé was at the height of his powers."[39]

Hergé biographer Benoît Peeters asserted that both The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure "hold a crucial position" in The Adventures of Tintin as they establish the "Tintin universe" with its core set of characters.[9] Focusing on the former comic, he described it as one of Hergé's "greatest narrative successes" through the manner in which it interweaves three separate plots.[9] He felt that while religious elements had been present in previous stories, they were even stronger in The Secret of the Unicorn and its sequel, something which he attributed to Van Melkebeke's influence.[10] Elsewhere he asserted that it "explores this prelude with extraordinary narrative virtuosity."[40]

Biographer Pierre Assouline stated that the story was "clearly influenced ... in spirit if not in detail" by Robert Louis Stevenson's book, Treasure Island in that it "seemed to cater to a need for escapism".[41] He described the adventure as "a new development in Hergé's work, a flight from the topical to epics of pirate adventures set in distant horizons".[41] Assouline also expressed the view that the ancestral figure of Sir Francis Haddock reflected Hergé's attempt to incorporate one of his own family secrets, that he had an aristocratic ancestor, into the story.[42]

Michael Farr believed that the "most remarkable" factor of the book was its introduction of Sir Francis Haddock, highlighting that in his mannerisms and visual depiction, he is "scarely distinguishable" from Captain Haddock.[43] He also highlighted that the scenes in which Captain Haddock relates the tale of his ancestor carries on the "merging of dreams and reality" that Hergé had "experimented with" in The Crab with the Golden Claws and The Shooting Star.[43] Noting that unlike The Shooting Star, this two-book story arc contains "scarcely an allusion to occupation and war", he praised the arc's narrative as "perfectly paced, without that feeling of haste" present in some of Hergé's earlier work.[15]

In his psychoanalytical study of the Adventures of Tintin, the academic Jean-Marie Apostolidès characterised the Secret of the Unicorn-Red Rackham's Treasure arc as being about the characters going on a "treasure hunt that turns out to be at the same time a search for their roots."[44] He stated that the arc delves into Haddock's ancestry, and in doing so "deals with the meanings of symbolic relations within personal life".[45] Discussing the character of Sir Francis Haddock, he states that this ancestral figure resembles both Tintin and Haddock, "the foundling and the bastard", thus making the duo brothers as well as close friends.[45] He adds that when Captain Haddock reenacts his ancestor's fight with Rackham, he adopts his "very soul, his mana, and is transformed in the process."[46] Comparing Sir Francis Haddock to Robinson Crusoe, he also draws a comparison between the way that the Caribbean natives deified Sir Francis Haddock by erecting a statue of him in the same manner that the Congolese deify Tintin at the end of Tintin in the Congo.[47] Apostolidès also discusses Red Rackham, noting that the name "Red" conjures up "the forbidden colour of blood and wine" while "Rackham" combines raca ("false brother")[a] with the French word for scum (racaille), then highlighting a potential link between Rackham's name and that of Rascar Capac, an Incan mummy who appears in The Seven Crystal Balls.[48] He further draws parallels between the model ships containing the secret parchments with the Arumbaya fetish containing a rare diamond which appears in The Broken Ear.[45]

Literary critic Tom McCarthy highlighted the scene in which Tintin was imprisoned in the Marlinspike crypt, observing that it had parallels with Tintin's exploration of tombs and other secret chambers throughout the series.[49] He identified the mystery left in Francis Haddock's parchments to be another appearance of Tintin's adventures being "framed by enigmas".[50] To this he adds that in solving the enigma, Tintin shows that he is "the best reader" in the series, and it is this which establishes him as "the oeuvre's hero".[51] McCarthy praised Hergé's Silk as one of the pivotal characters in the series who can "exude a presence far beyond that which we might expect from a novelist, let alone a cartoonist".[52]

Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle discussed the scene in the story in which Tintin was imprisoned in the crypt of Marlinspike Hall. He stated that in this section, "Hergé offers us an embedded story, a kind of interlude in which the artist, setting aside the use value of objects, takes the liberty of giving them mischievous powers, akin to a certain surrealism."[53]

Adaptations

In 1957, the animation company Belvision Studios produced Hergé's Adventures of Tintin, a series of daily five-minute colour adaptations based upon Hergé's original comics. The Secret of the Unicorn was the fourth to be adapted in the second animated series; it was directed by Ray Goossens and written by Greg, a well-known cartoonist who was to become editor-in-chief of Tintin magazine.[54]

In 1991, a collaboration between the French studio Ellipse and the Canadian animation company Nelvana adapted 21 of the stories into a series of episodes. The Secret of the Unicorn was the ninth story of The Adventures of Tintin to be produced and was divided into two thirty-minute episodes. Directed by Stéphane Bernasconi, the series has been praised for being "generally faithful" to the original comics, to the extent that the animation was directly adopted from Hergé's original panels.[55]

A 2011 motion capture feature film The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, directed by Steven Spielberg and produced by Peter Jackson, was released in most of the world October–November 2011 and in the US on 21 December 2011. The film is based partly upon The Secret of the Unicorn and partly on both Red Rackham's Treasure and The Crab with the Golden Claws.[56] A video-game tie-in to the movie was released October 2011.[57]

References

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Hergé 1959, pp. 1–12.

- ^ Hergé 1959, pp. 12–62.

- ^ Assouline 2009, pp. 70–71; Peeters 2012, pp. 116–118.

- ^ Assouline 2009, p. 72; Peeters 2012, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Goddin 2009, p. 73; Assouline 2009, p. 72.

- ^ Assouline 2009, p. 73; Peeters 2012.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 99; Farr 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d Peeters 2012, p. 143.

- ^ a b Peeters 2012, p. 144.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 54; Goddin 2009, p. 102.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 54; Peeters 2012, p. 143.

- ^ a b Thompson 1991, p. 112.

- ^ Farr 2001, p. 105.

- ^ a b Farr 2001, p. 112.

- ^ Goddin 2009, p. 104.

- ^ Assouline 2009, p. 88; Farr 2001, p. 111; Peeters 2012, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b Peeters 1989, p. 75; Farr 2001, p. 111.

- ^ Farr 2001, pp. 108–109; Horeau 2004, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Horeau 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Peeters 1989, p. 77; Thompson 1991, p. 115; Farr 2001, p. 106; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Peeters 1989, p. 76; Thompson 1991, p. 115; Farr 2001, p. 106; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Peeters 1989, p. 75; Thompson 1991, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Thompson 1991, p. 113.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 113; Farr 2001, p. 105.

- ^ a b Farr 2001, p. 111.

- ^ Lavery 2003, p. 158; Davies 2004.

- ^ a b c Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Goddin 2009, p. 124.

- ^ Goddin 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Goddin 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Peeters 2012, p. 145.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 121; Farr 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Farr 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Horeau 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 115; Farr 2001, p. 111.

- ^ a b Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Goddin 2009, p. 110.

- ^ Peeters 1989, p. 75.

- ^ a b Assouline 2009, p. 88.

- ^ Assouline 2009, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Farr 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Apostolidès 2010, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Apostolidès 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Apostolidès 2010, p. 143.

- ^ Apostolidès 2010, p. 138.

- ^ a b Apostolidès 2010, p. 137.

- ^ McCarthy 2006, pp. 65–66.

- ^ McCarthy 2006, p. 18.

- ^ McCarthy 2006, p. 21.

- ^ McCarthy 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Fresnault-Deruelle 2010, p. 125.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 90.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph: Michael Farr 2011.

- ^ IGN 2011.

Bibliography

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010) [2006]. The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults. Jocelyn Hoy (translator). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6031-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, J.D. (2004). "Haddock, Sir Richard (c.1629–1715)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farr, Michael (17 October 2011). "The inspiration behind Steven Spielberg's Tintin". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Fresnault-Deruelle, Pierre (2010). "The Moulinsart Crypt". European Comic Art. 3 (2): 119–144.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goddin, Philippe (2009). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume 2: 1937-1949. Michael Farr (translator). San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-724-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hergé (1959) [1943]. The Secret of the Unicorn. Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner (translators). London: Egmont. ISBN 978-0-613-71791-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Horeau, Yves (2004). The Adventures of Tintin at Sea. Michael Farr (translator). London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6119-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lavery, Brian (2003). The Ship of the Line — Volume 1: The Development of the Battlefleet 1650-1850. Conway Maritime Post. ISBN 0-85177-252-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCarthy, Tom (2006). Tintin and the Secret of Literature. London: Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-831-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peeters, Benoît (1989). Tintin and the World of Hergé. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "The Adventures of Tintin [The Game] Review". IGN. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- The Secret of the Unicorn at the Official Tintin Website

- The Secret of the Unicorn at Tintinologist.org