The Talons of Weng-Chiang

| 091 – The Talons of Weng-Chiang | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor Who serial | |||

| File:Talons of Weng Chiang.jpg The Doctor confronts Magnus Greel with the key to Greel's Time Cabinet. | |||

| Cast | |||

Others

| |||

| Production | |||

| Directed by | David Maloney | ||

| Written by | Robert Holmes | ||

| Script editor | Robert Holmes | ||

| Produced by | Philip Hinchcliffe | ||

| Executive producer(s) | None | ||

| Music by | Dudley Simpson | ||

| Production code | 4S | ||

| Series | Season 14 | ||

| Running time | 6 episodes, 25 minutes each | ||

| First broadcast | 26 February – 2 April 1977 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| |||

The Talons of Weng-Chiang is the sixth and final serial of the 14th season of the British science fiction television series Doctor Who, which was first broadcast in six weekly parts from 26 February to 2 April 1977.[1]

Set in 19th-century London and written by the series' script editor at the time, Robert Holmes, The Talons of Weng-Chiang was also the final serial to be produced by Philip Hinchcliffe, who had worked on the series for three seasons. One of the most popular serials from the series' original run on television, The Talons of Weng-Chiang has continued to receive acclaim from reviewers and it has been repeatedly voted one of the best stories by fans. Despite this, criticism has been directed towards the serial's representation of Chinese characters and an unconvincing giant rat featured in the story.

Plot

This episode's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (June 2017) |

The Doctor and Leela arrive in London so that Leela can learn about the customs of her ancestors, specifically the musical theatre of Victorian England. Performing at the Palace Theatre on an extended run is the stage magician Li H'sen Chang, although the Doctor did hope to catch Little Tich. On their way to the Palace Theatre, the Doctor and Leela encounter a group of Chinese men who have apparently killed a cab driver. They attempt to silence the Doctor and Leela but are frightened away by the distant whistle of an approaching policeman. All but one escape, and he, the Doctor and Leela are taken to the local police station.

At the station, Li H'sen Chang is called in to act as an interpreter, but unbeknownst to everyone else he is the leader of the group and he secretly gives the captive henchman a pill of concentrated scorpion venom, which the henchman takes immediately and dies. The Doctor, upon a brief examination of the body, finds a scorpion tattoo—the symbol of the Tong of the Black Scorpion, devout followers of an ancient god, Weng-Chiang.

The body is taken to the local mortuary, along with the body of the cabbie which had just been found floating in the river. There they meet Professor Litefoot, who is performing the autopsies. The cabbie is Joseph Buller, who had been looking for his wife Emma, the latest in a string of missing women in the area. Buller had gone down to the Palace Theatre where he had confronted Chang about his wife's disappearance, threatening to report Chang to the police if she was not returned to him. Chang, fearful of discovery, had sent his men, including the diminutive Mr Sin, to kill Buller. Chang is in the service of Magnus Greel, a despot from the 51st century who had fled from the authorities in a time cabinet, now masquerading as the Chinese god Weng-Chiang. The technology of the cabinet is based on "zygma energy," which is unstable and has disrupted Greel's own DNA, deforming him horribly. This forces him to drain the life essences from young women to keep himself alive. At the same time, Greel is in search of his cabinet, taken from him by Chinese Imperial soldiers and in turn given by the Imperial Court to Professor Litefoot's parents as a gift. Mr Sin is also from the future, but is a robotic toy constructed with the cerebral cortex of a pig. It is better known as the Peking Homunculus, a vile thing that almost caused World War Six when its organic pig part took over the toy's functions.

Greel tracks down the time cabinet and steals it, whilst concurrently the Doctor tracks Greel to the sewers underneath the Palace Theatre, aided (rather clumsily) by the theatre's owner, Henry Gordon Jago. However, Greel has already fled his lair, abandoning Chang to the police. Chang escapes but only to be mauled by one of the giant rats—products of Greel's experiments, which were then used to guard his sewer hideout.

While the Doctor and Leela try to find Greel's new hideout, Jago comes across a bag of future technological artefacts, among which is the key to the time cabinet. He takes it to Professor Litefoot's house, and there, after leaving the artefacts and a note for the Doctor, the Professor and Jago set out to follow anyone coming around the Palace Theatre in search of the bag. However, they are captured for their efforts. Meanwhile, the Doctor and Leela happen upon Chang in an opium den, already half dead from his injuries and the narcotic; there, he tells them that Greel can be found in the House of the Dragon but falls into rambling and dies before telling them its exact location. He does leave them a Chinese puzzle that tells the Doctor that Greel's lair is in a Boot Court somewhere.

The Doctor and Leela return to Professor Litefoot's house. There they find the note and the key to the time cabinet. They decide to wait for Greel and his henchmen. When they arrive, the Doctor uses the key, a fragile crystal known as a Trionic Lattice, as a bargaining chip. He asks to be taken to the House of the Dragon, offering the key in exchange for Litefoot and Jago's release. Instead, Greel overpowers the Doctor and locks him in with the two amateur sleuths.

Leela, who had been left at Litefoot's house at the Doctor's behest, has followed them and confronts Greel. She is captured and set in his life-essence extraction machine, a catalytic extraction chamber, but before her life essence is drained in order to feed Greel, the Doctor, Jago and Litefoot escape and rescue her. In a final confrontation, Mr Sin turns on Greel as the Doctor convinces it that Greel escaping in his time cabinet will create a catastrophic implosion. The Doctor defeats Greel by forcibly pushing him into his own catalytic extraction chamber, thus damaging it and causing it to overload. Having fallen victim to his own machine, Greel suffers Cellular Collapse and disintegrates. Enraged by the events, the Peking Homunculus attacks Leela, but the Doctor manages to remove its prime fuse and damage it beyond repair before bringing the Zygma Experiment to a permanent end by destroying the lattice.

As the Doctor prepares the TARDIS, Litefoot attempts to explain tea to Leela, only to baffle her further. The Doctor and Leela bid farewell to Jago and Litefoot as they enter the TARDIS. Confused by the police box, Litefoot is astonished by its de-materialisation, a stunt which Jago remarks that even Li H'sen Chang could have appreciated.

Continuity

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

This is the only story from the Tom Baker era in which he is not seen wearing one of his trademark scarves, his attire instead resembling that of Sherlock Holmes. Leela is not shown wearing her leathers. According to the textual information track on the DVD release, this change in costume was supposed to be permanent as the Doctor and Leela established a Professor Higgins/Eliza Doolittle-style relationship, but the idea was soon dropped. At one point, the Doctor empties his pockets, revealing a number of odds and ends, including a bag of his trademark jelly baby sweets and a toy Batmobile.[2] This story alludes to the First Doctor serial Marco Polo, when the Doctor remarks, "I haven't been in China for 400 years."

The Virgin Missing Adventures spin off novel The Shadow of Weng-Chiang by David A. McIntee is a sequel to this story, and again features Mr Sin, this time under the control of Li H'sen Chang's daughter Hsien-Ko, who seeks to divert Greel to 1937 so that she can torture him for his role in her father's death. The Doctor encounters Professor Litefoot again in the Eighth Doctor Adventures novel The Bodysnatchers by Mark Morris, although the Eighth Doctor claims to merely be an 'associate' of the Fourth Doctor rather than revealing that he is the same man. The Time Agents who pursue Greel are featured in the Eighth Doctor Adventures Eater of Wasps and Emotional Chemistry. The Ninth and Tenth Doctor's former companion and leader of Torchwood, Jack Harkness identified himself as an ex-Time Agent also from the 51st century.

The Mahogany Murderers is a Big Finish Productions audio drama in which Jago & Litefoot (played by the original actors) relate another adventure they shared, but without the Doctor's help. There have been further audio dramas of "Jago & Litefoot", including a brief period where they travel with the Sixth Doctor. Magnus Greel's days as The Minister of Justice are explored in the 2012 prequel audio story The Butcher of Brisbane, featuring the Fifth Doctor, being careful not to change his own past as he becomes involved in the events that forced Greel to flee into the past.

Production

Robert Banks Stewart's story outline ("The Foe from the Future") inspired elements of this serial. "The Foe from the Future" was adapted by Big Finish Productions as an audio play in 2012. Working titles for this story included The Talons of Greel. This was the final Doctor Who story produced by Philip Hinchcliffe. Hinchcliffe was succeeded by Graham Williams as the series producer, who sat in on this story's production. This story featured the first Doctor Who work by John Nathan-Turner as series production unit manager. Nathan-Turner would succeed Williams as the show's producer from 1980 to 1989.

The Talons of Weng-Chiang featured two separate blocks of location shooting. As planned, the serial was to have a week of location filming for the exterior footage, which took place at various locations in London, with the majority in the area around Wapping,[3] in mid-December 1976, followed by three studio recording sessions. Producer Philip Hinchcliffe was able to negotiate the swapping of one of the planned studio sessions for the use of an outside broadcast video crew, which led to the second block of location shooting in early January 1977, encompassing a week in Northampton, the majority of which was spent at the Royal Theatre.[4]

A large pile of straw seen in one scene was placed there to cover a modern car that had not been moved off the street.[3] The production team briefly considered giving Jago and Litefoot their own spin-off series.

The production of this serial featured in a BBC 2 documentary, Whose Doctor Who (1977), presented by Melvyn Bragg, which was part of the arts series The Lively Arts. Including interviews with Tom Baker, Philip Hinchcliffe and fans of the series, it was the first in-depth documentary made by the BBC on the series and was transmitted on the day following the final episode. The programme is included as an extra on the DVD releases of The Talons of Weng-Chiang.

Cast notes

Deep Roy, who played Mr. Sin, had an uncredited role as an unnamed alien trade delegate in The Trial of a Time Lord: Mindwarp. Dudley Simpson – who composed much of the music for Doctor Who in the 1960s, and '70s – has a cameo as the conductor of Jago's theatre orchestra. Michael Spice appears in this story as the main villain, Magnus Greel. He also provided the voice of Morbius in the previous season's The Brain of Morbius. John Bennett had previously appeared in Doctor Who as General Finch in Invasion of the Dinosaurs. Christopher Benjamin had previously appeared in Inferno as Sir Keith Gold and would return to play Colonel Hugh in "The Unicorn and the Wasp".

Outside references

There are a number of references to the Sherlock Holmes novels by Arthur Conan Doyle:

- The Doctor is dressed in a similar way as the stereotype Sherlock Holmes caricature (although the Holmes of Doyle's stories would never have worn a deerstalker and Inverness cape in town) and uses sayings and mannerisms similar to Holmes'.

- Professor Litefoot is a similar character to Sherlock Holmes' colleague Dr Watson and he has a housekeeper called Mrs Hudson (the same name as the housekeeper at 221b Baker Street in the Sherlock Holmes novels).

- At one point the Doctor says to Litefoot "...elementary, my dear Litefoot".

In so far as Magnus Greel is a hideously deformed character living beneath a 19th-century theatre who convinces a performer that he is a spirit rather than a man, the story is also reminiscent of The Phantom of the Opera. When Chang calls the Doctor to the stage, there is a short musical excerpt from Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado. The fourth episode features a rendition of the popular song "Daisy Bell", written in 1892.

Broadcast and reception

| Episode | Title | Run time | Original air date | UK viewers (millions) [5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Part One" | 24:44 | 26 February 1977 | 11.3 |

| 2 | "Part Two" | 24:26 | 5 March 1977 | 9.8 |

| 3 | "Part Three" | 21:56 | 12 March 1977 | 10.2 |

| 4 | "Part Four" | 24:30 | 19 March 1977 | 11.4 |

| 5 | "Part Five" | 24:49 | 26 March 1977 | 10.1 |

| 6 | "Part Six" | 23:26 | 2 April 1977 | 9.3 |

Paul Cornell, Martin Day, and Keith Topping, in The Discontinuity Guide (1995), praised the double act of Jago and Litefoot and called the serial, "One of the great moments of Doctor Who history - an effortless conquering of the pseudo-historical genre with a peerless script."[6] In The Television Companion (1998), David J. Howe and Stephen James Walker were full of similar praise for the script, direction, the characters, and acting.[7] In 2010, Mark Braxton of Radio Times described the serial as atmospheric and "a triumph of pastiche over cliché". He praised the villains and Leela.[8] The A.V. Club reviewer Christopher Bahn wrote that the story was good at "genre-blending" and homages.[9]

In 2008, The Daily Telegraph named the serial the best of the "10 greatest episodes of Doctor Who" up to that point, writing, "The top-notch characterisation, direction and performances, with Tom Baker at the top of his game, make this the perfect Doctor Who story."[10] This story was voted the best Doctor Who story ever in the 2003 Outpost Gallifrey poll to mark the series' 40th anniversary, narrowly beating The Caves of Androzani.[11] In Doctor Who Magazine's 2009 "Mighty 200" poll, asking readers to rank all of the then-released 200 stories, The Talons of Weng-Chiang came in fourth place.[12] In a similar poll in 2014, magazine readers ranked the episode in sixth place.[13] Russell T Davies, lead writer and executive producer for Doctor Who's 21st-century revival, praised this serial, saying, "Take The Talons of Weng-Chiang, for example. Watch episode one. It's the best dialogue ever written. It's up there with Dennis Potter. By a man called Robert Holmes. When the history of television drama comes to be written, Robert Holmes won't be remembered at all because he only wrote genre stuff. And that, I reckon, is a real tragedy."[14]

Although the script and the general production of the serial has been highly praised, some commentators have criticised elements of it such as the realisation of the giant rat and the depiction of the Chinese characters, which has been alleged to be racist. Mark Braxton, in his Radio Times review, acknowledged the failings of the giant rat.[8] In his volume of British history State of Emergency, Dominic Sandbrook criticizes the giant rat for being "one of the worst-realized monsters not merely in the show's history, but in the history of human entertainment."[15] Howe and Walker noted that its flaw was the realisation of the giant rat, though the story "still contains its fair share of gruesome and disturbing material".[7] Some of the English characters display racist attitudes towards the Chinese characters, which go unchallenged by the Doctor, who normally stands up for marginalized groups.[16] Meanwhile the Chinese immigrants themselves are portrayed in a stereotypical fashion – other than Li H'sen Chang (a major villain who is himself akin to Fu Manchu, but portrayed by a white actor – another source of criticism),[17] all of the Chinese characters are coolies or members of Tong gangs. The Chinese Canadian National Council for Equality characterized the content of the episodes as "dangerous, offensive, racist stereotyping [which] associate the Chinese with everything fearful and despicable". As a result of their complaint to TVOntario, the Canadian channel chose not to broadcast all six episodes of the serial.[18] Christopher Bahn wrote, "If it wasn't for the uncomfortably racist aspects of the story, it'd be close to perfection."[9]

Commercial Releases

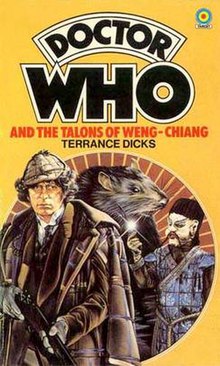

In print

| |

| Author | Terrance Dicks |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Jeff Cummins |

| Series | Doctor Who book: Target novelisations |

Release number | 61 |

| Publisher | Target Books |

Publication date | 15 November 1977 |

| ISBN | 0-426-11973-8 |

A novelisation of this serial, written by Terrance Dicks, was published by Target Books in November 1977, entitled Doctor Who and The Talons of Weng-Chiang.

The script was published by Titan Books in November 1989, entitled "Doctor Who The Scripts The Talons of Weng-Chiang" and edited by John McElroy.[19]

Home media

The Talons of Weng-Chiang was released in omnibus format on VHS in the UK in 1988, having previously been available only in Australia. The fight scene between the Doctor and the Tong of the Black Scorpion in Part One was slightly edited to remove the use of the nunchaku (or chain-sticks), which were at the time classed as illegal weapons in the UK and couldn't be shown on-screen — a ruling which has since changed.

The story was released in complete and unedited episodic format on DVD in April 2003 in a two-disc set as part of the Doctor Who 40th Anniversary Celebration releases, representing the Tom Baker years. On 2 September 2008, this serial was released for sale on iTunes. A special edition version of the story was released on DVD as part of the "Revisitations 1" box set in October 2010.

References

- ^ Debnath, Neela (21 September 2013). "Review of Doctor Who 'The Talons of Weng-Chiang' (Series 14)". The Independent.

- ^ DVD textual information track

- ^ a b https://drwhointerviews.wordpress.com/category/david-maloney/

- ^ Sullivan, Shannon (2007-08-07). "The Talons of Weng-Chiang". A Brief History of Time Travel. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ "Ratings Guide". Doctor Who News. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1995). "The Talons of Weng-Chiang". The Discontinuity Guide. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-426-20442-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Howe, David J & Walker, Stephen James (1998). Doctor Who: The Television Companion (1st ed.). London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-40588-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Braxton, Mark (14 September 2010). "Doctor Who: The Talons of Weng-Chaing". Radio Times. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ a b Bahn, Christopher (23 October 2011). "The Talons of Weng-Chiang". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "The 10 greatest episodes of Doctor Who ever". The Daily Telegraph. 2 July 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ "Outpost Gallifrey 2003 Reader Poll". Outpost Gallifrey. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Haines, Lester (17 September 2009). "Doctor Who fans name best episode ever". The Register. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ "The Top 10 Doctor Who stories of all time". Doctor Who Magazine. June 21, 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Richard (2007-03-11). "Master of the universe". The Sunday Telegraph. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ Sandbrook, Dominic (2010). State of Emergency: The Way We Were: Britain, 1970–1974. Allen Lane. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-846-14031-0.

... and a giant rat – the latter one of the worst-realized monsters not merely in the show's history, but in the history of human entertainment.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Stanish, Deborah. Chicks Unravel Time. Mad Norwegian Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1935234128.

- ^ Gillatt, Gary (1998). Doctor Who: From A to Z. London: BBC. pp. 35–39. ISBN 0563405899.

- ^ "Chinese object to Dr. Who". Regina Leader-Post. 7 November 1980. p. 12.

- ^ Holmes, Robert (November 1989). McElroy, John (ed.). Doctor Who - The Scripts: The Talons of Weng-Chiang. London: Titan Books. p. 4. ISBN 1-85286-144-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- The Talons of Weng-Chiang at BBC Online

- The Talons of Weng-Chiang on Tardis Wiki, the Doctor Who Wiki

- Template:Brief

- Template:Doctor Who RG