To Live and Die in L.A. (film)

| To Live and Die in L.A. | |

|---|---|

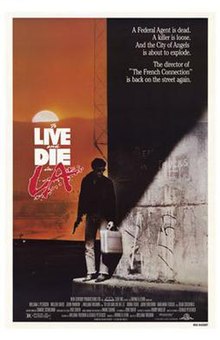

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William Friedkin |

| Screenplay by | William Friedkin Gerald Petievich |

| Produced by | Irving H. Levin Bud S. Smith |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robby Müller |

| Edited by | M. Scott Smith |

| Music by | Wang Chung |

Production companies | New Century Productions SLM Production Group |

| Distributed by | United Artists MGM/UA Entertainment Co. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6,000,000 |

| Box office | $17,300,000 |

To Live and Die in L.A. is a 1985 American action thriller film directed by William Friedkin and based on the novel by former U.S. Secret Service agent Gerald Petievich, who co-wrote the screenplay with Friedkin. The film features William Petersen, Willem Dafoe and John Pankow among others. Wang Chung composed and performed the original music soundtrack. The film tells the story of the lengths to which two Secret Service agents go to arrest a counterfeiter.

Plot

Richard Chance and Jimmy Hart are United States Secret Service agents assigned as counterfeiting investigators in its Los Angeles field office. Chance has a reputation for reckless behavior, while Hart is three days away from retirement. Alone, Hart stakes out a warehouse in the desert thought to be a print house of counterfeiter Rick Masters. After Masters and Jack, his bodyguard, kill Hart, Chance explains to his new partner, John Vukovich, that he will take Masters down no matter what.

The two agents attempt to get information on Masters by putting one of his criminal associates, attorney Max Waxman, under surveillance. Vukovich falls asleep on watch, and consequently they fail to catch Masters in the act of murdering Waxman. While Vukovich wants to go by the book, Chance becomes increasingly reckless and unethical in his efforts to catch Masters. While Chance relies on his sexual-extortion relationship with parolee/informant Ruth for information, Vukovich meets privately with Masters' attorney, Bob Grimes. Grimes, acknowledging a potential conflict of interest that could ruin his legal practice, agrees to set up a meeting between his client and the two agents, who engage Masters by posing as bankers from Palm Springs interested in Masters' counterfeiting services. Masters is reluctant to work with them, but ultimately agrees to print them $1,000,000 worth of fake bills.

In turn, Masters demands $30,000 in front money, which is three times the authorized agency limit for buy money. To get the cash, Chance persuades Vukovich to aid him in robbing Thomas Ling, a man whom Ruth previously told Chance is bringing $50,000 cash to purchase stolen diamonds. Chance and Vukovich intercept Ling at the train station and seize the cash in an industrial area. Ling's cover people follow them, though, open fire and accidentally shoot Ling. Chance and Vukovich try to evade them through the streets, freeways and even one of the flood control channels, before a final escape by going the wrong way on the freeway. The next day, the end of their daily briefing includes an FBI bulletin that Ling was an undercover FBI agent, kidnapped, robbed and murdered while on a sting operation. Only a generic description of the assailants and their vehicle is given. While Chance and Vukovich did not kill Ling, Vukovich is nonetheless consumed by guilt, while Chance is apathetic and focused solely on getting Masters. Unable to persuade Chance to come clean about their role in Ling's death, Vukovich meets with Grimes, who advises him to turn himself in and testify against Chance in exchange for a lighter sentence. Vukovich refuses to implicate his partner.

Chance and Vukovich meet with Masters for the exchange. After inspecting the counterfeit million, the agents attempt to arrest Masters and Jack, but Jack pulls a shotgun. Jack and Chance fatally shoot each other, and Masters escapes. Vukovich gives chase, going to a warehouse a previous informant had told them about. By the time he arrives, Masters has set fire to everything inside, destroying all evidence. Vukovich confronts Masters and during a brief struggle, Masters asks Vukovich why he did not take Grimes' advice to turn his partner in, revealing that Grimes was working on Masters' behalf all along. While Vukovich is stunned at the revelation, Masters grabs a board and knocks him unconscious. Masters then covers Vukovich with shredded paper and is about to set him on fire when Vukovich wakes up and shoots Masters. Masters drops his lighter and accidentally sets himself ablaze, while Vukovich empties his gun on the burning man, killing him.

Vukovich visits Ruth as she packs up to leave L.A. He mentions Chance's death, deducing she had known all along that Ling was FBI. He knows Chance had left her with the remaining cash that his agency now wants back, but Ruth said she needed it to pay debts she owed. Vukovich declares that Ruth is working for him now, turning into the same "whatever it takes" agent that his partner was.

Cast

|

|

Production

Director William Friedkin was given Gerald Petievich's novel in manuscript form and found it very authentic.[1] The filmmaker was also fascinated by the "absolutely surrealistic nature" of the job of a Secret Service agent outside of Washington, D.C.[2] When the film deal was announced, Petievich was investigated by a rival for a pending office promotion, and felt that "a lot of resentment against me for making the movie" and "some animosity against me in the Secret Service" existed, exacerbated by the agent in the Los Angeles field office who suddenly resigned a few weeks after initiating the investigation.[3] SLM Productions, a tribunal of financiers, worked with Friedkin on a ten-picture, $100 million deal with 20th Century Fox but when the studio was purchased by Rupert Murdoch, one of the financiers pulled the deal and took it to MGM.[4]

Casting

Friedkin had a $6 million budget to work with while the cast and crew worked for relatively low salaries.[2] As a result, he realized that the film would have no movie stars in it.[4] William Petersen was acting in Canada when asked to fly to New York City and meet with the director. Half a page into his reading, Friedkin told him he had the part. The actor was drawn to the character of Chance as someone who had a badge and a gun and how it not only made him above the law, but also "above life and death in his head".[2] The actor found the experience of being this character and making the film "amazing" and "intoxicating".[2] He called fellow Chicago actor John Pankow and brought him to Friedkin's apartment the day after being cast as Chance, recommending him for the role of Vukovich. The director agreed on the spot.[4]

Former Secret Service agent and author Gerald Petievich, who wrote the book the movie is based on, appears in a cameo as a fellow Secret Service agent.

Screenplay

The basic plot, characters, and much of the dialogue of the film is drawn from Petievich's novel, but Friedkin added the opening terrorist sequence, the car chase, and clearer, earlier focus on the showdown between Chance and Masters.[5] Petievich said that Friedkin wrote a number of scenes but when there was a new scene or a story needed to be changed, he wrote it. The director admits that Petievich created the characters and situations and that he used a lot of dialogue but that he wrote the screenplay, not Petievich.[5]

Principal photography

The director wanted to make an independent film and collaborate with people who could work fast, like cinematographer Robby Müller and his handpicked crew who were non-union members.[2] Friedkin shot everything on location and worked quickly, often using the first take to give a sense of immediacy. He did not like to rehearse but would create situations where the actors thought they were rehearsing a scene when actually they were shooting a take. Friedkin did this just in case he got something he could use. To this end, he let scenes play out and allowed the actors to stay in character and improvise.[2] For example, during the scene where Chance visits Ruthie at the bar where she works, Friedkin allowed Petersen and actress Darlanne Fleugel devise their own blocking and told Müller, "Just shoot them. Try and keep them in the frame. If they're not in the frame, they're not in the movie. That's their problem".[6]

The shot of Petersen running along the top of the dividers between the terminal's moving sidewalk at the Los Angeles International Airport got the filmmakers into trouble with the airport police.[2] The airport had prohibited this action, mainly for Petersen's safety, as they felt that their insurance would not have covered him had he hurt himself. The actor told Friedkin that they should do the stunt anyway so the director proposed that they treat it like a rehearsal but have the cameras rolling and shoot the scene, angering airport officials.[2]

The counterfeiting montage looks authentic because Friedkin consulted actual counterfeiters who had done time. The "consultant" actually did the scenes that do not show actor Willem Dafoe on camera to give this sequence more authenticity[2] even though the actor learned how to print money.[7] Over one million dollars of counterfeit money was produced but with three deliberate errors so that it could not be used outside the film. The filmmakers burned most of the fake money but some leaked out, was used, and linked back to the production. The son of one of the crew members tried to use some of the prop money to buy candy at a local store and was caught.[8] Three FBI agents from Washington, D.C. interviewed 12-15 crew members including Friedkin who screened the workprint for them. He offered to show the film to the Secretary of the Treasury and take out anything that was a danger to national security. That was the last he heard from the government.[8]

The wrong-way car chase on a Los Angeles freeway sequence was one of the last things shot in the film and it took six weeks to shoot.[2] At this point, Friedkin was working with a very stripped down crew. He came up with the idea of staging the chase against the flow of traffic on February 25, 1963 when he was driving home from a wedding in Chicago.[8] He fell asleep at the wheel and woke up in the wrong lane with oncoming traffic heading straight for him. He swerved back to his side of the road and for the next 20 years wondered how he was going to use it in a film. He told stunt coordinator Buddy Joe Hooker that if they could come up with a chase better than the one in The French Connection then it would be in the film. If not, he would not use it. Petersen did a lot of his own driving during this sequence and actor John Pankow's stressed out reactions were real.[2] Three weekends were spent on sections of the Terminal Island Freeway near Wilmington, California that were closed for four hours at a time to allow the crew to stage the chaotic chase.[9] With delays, the film ran a reported $1 million over budget.[10]

Adding to the chaotic feeling of the chase, Friedkin staged it so that the freeway traffic flow was reversed. That is that the normal traffic in the scene has the drivers driving on their left in the left hand lanes (as in Britain) while the cars driving against the flow were driving on their right (as would be usual in North America).

Post-production

As early as the day he cast Petersen, Friedkin thought about killing off Chance towards the end of the film, but according to editor Bud Smith, Vukovich was supposed to be the one who was killed.[11] The climactic scene in which Chance is killed was not very well received by MGM executives, who found it to be too negative.[2] To satisfy the studio heads, he shot a second ending, in which Chance survives the shotgun blast and, presumably as an internal punishment, he and Vukovich are transferred to a remote Secret Service station in Alaska, and watch their boss, Thomas Bateman, being interviewed on television.[2] Friedkin previewed the alternate ending and kept the original.[7]

Reception

Box-office

To Live and Die in L.A. premiered in the United States on November 1, 1985 in 1,135 theaters where it grossed $3.6 million on its opening weekend. It went on to make $17.3 million in North America, well above its $6 million budget.[12]

Critical response

Roger Ebert, film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave the film four out of four stars and wrote, "[T]he movie is also first-rate. The direction is the key. Friedkin has made some good movies ... and some bad ones. This is his comeback, showing the depth and skill of the early pictures".[13] He went on to praise Petersen, "a Chicago stage actor who comes across as tough, wiry and smart. He has some of the qualities of a Steve McQueen".[13] Critic Janet Maslin was dismissive of the film, and wrote, "Today, in the dazzling, superficial style that Mr. Friedkin has so thoroughly mastered, it's the car chases and shootouts and eye-catching settings that are truly the heart of the matter".[14] David Ansen, critic for Newsweek, wrote, "Shot with gritty flamboyance by Robby Muller, cast with a fine eye for fresh, tough-guy faces, To Live and Die in L.A. may be fake savage, but it's fun".[15]

The staff at Variety magazine were not impressed with the film and wrote that it was over the top: "To Live and Die in L.A. looks like a rich man's Miami Vice. William Friedkin's evident attempt to fashion a West Coast equivalent of his 1971 The French Connection is engrossing and diverting enough on a moment-to-moment basis but is overtooled ... Friedkin keeps dialog to a minimum, but what conversation there is proves wildly overloaded with streetwise obscenities, so much so that it becomes something of a joke".[16] In his review for the Washington Post, Paul Attanasio wrote, "To Live and Die in L.A. will live briefly and die quickly in L.A., where God hath no wrath like a studio executive with bad grosses. Then again, perhaps it's unfair to hold this overheated and recklessly violent movie to the high standard established by Starsky and Hutch".[17] Jay Scott, in his review for the Globe and Mail, wrote, "Pity poor Los Angeles: first the San Andreas fault and now this. The thing about it is, To Live and Die in L.A., for all its amorality and downright immorality, is a cracker-jack thriller, tense and exciting and unpredictable, and more grimy fun than any moralist will want it to be".[18] Time criticized its "brutal, bloated car-chase sequence pilfered from Friedkin's nifty The French Connection", and called it "a fetid movie hybrid: Miami Vile".[19]

Almost two decades later, a review in The Digital Fix called the film "A sun-bleached study in corruption and soul-destroying brutality, this film by the notoriously erratic but sometimes brilliant William Friedkin is nasty, cynical and incredibly good."[20] The film was voted as the 19th best film set in Los Angeles in the last 25 years by a group of Los Angeles Times writers and editors with two criteria: "The movie had to communicate some inherent truth about the L.A. experience, and only one film per director was allowed on the list".[21]

Accolades

Wins

- Cognac Festival du Film Policier: Audience Award; William Friedkin; 1986.

- Stuntman Awards: Stuntman Award; Best Feature Film Vehicular Stunt, Dick Ziker and Eddy Donnol; Most Feature Film Spectacular Sequence, Dick Ziker; 1986.

Impact

Although criticized at the time for the lack of accomplished celebrities in its cast,[22] many of the actors have gone on to become established stars, most notably Willem Dafoe (Platoon,The Last Temptation of Christ, Mississippi Burning, Spider-Man, The English Patient, Wild at Heart), William Petersen (Manhunter, CSI), John Pankow (Mad About You), Jane Leeves (Frasier), and John Turturro (Quiz Show, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Big Lebowski).

Soundtrack

According to Friedkin, the main reason he chose Wang Chung to compose the soundtrack was because the band "stands out from the rest of contemporary music ... What they finally recorded has not only enhanced the film, it has given it a deeper, more powerful dimension".[23] He wanted them to compose the score for his film after listening to the band’s previous album, Points on the Curve. He was so taken with the album that he took one of the songs straight off the album, "Wait", and used it as part of the soundtrack. "Wait" plays at the end credits of the film. Every song on the soundtrack, excluding the title song and "Wait", was written and recorded within a two-week period. Only after Wang Chung saw a rough draft of the film did they produce the title song.[23]

An original motion picture soundtrack was released on September 30, 1985, by Geffen Records. The album contained eight tracks. The album’s title song, "To Live and Die in L.A.", (with a music video also directed by Friedkin), made it on the Billboard Hot 100 where it peaked at #41 in the United States.

Home media

A DVD was released by MGM Home Entertainment on December 2, 2003. The DVD contains a new restored wide-screen transfer, an audio commentary featuring director Friedkin where he relates stories about the making of the movie, a half-hour documentary featuring the main characters, a deleted scene showing a distraught Vukovich bothering his soon-to-be ex-wife at her apartment, and the alternate ending Friedkin refused to use, in which the two Secret Service partners survive but are transferred to Alaska while their supervisor Bateman is promoted and takes credit for stopping Masters. On February 2, 2010, the film was released on Blu-ray containing all of the previous special features that were included on the DVD release.[24]

TV Series

William Friedkin is developing a TV series based on the movie for WGN America.[25]

References

Notes

- ^ Segaloff 1990, p. 224.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Arick, Michael M (2003). "Counterfeit World: The Making of To Live and Die in L.A.". To Live and Die in L.A. Special Edition DVD =. MGM.

- ^ Segaloff 1990, p. 225.

- ^ a b c Segaloff 1990, p. 226.

- ^ a b Segaloff 1990, p. 230.

- ^ Segaloff 1990, p. 231.

- ^ a b Segaloff 1990, p. 233.

- ^ a b c Segaloff 1990, p. 234.

- ^ Segaloff 1990, pp. 234-235.

- ^ Segaloff 1990, p. 235.

- ^ Segaloff 1990, p. 232.

- ^ "To Live and Die in L.A.". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (November 1, 1985). "To Live and Die in L.A.". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (November 1, 1985). "From Friedkin". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Ansen, David (November 11, 1985). "Law of the Urban Jungle". Newsweek. p. 80.

- ^ "To Live and Die in L.A.". Variety. November 1, 1985. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Attanasio, Paul (November 4, 1985). "Counterfeit Cops". Washington Post. p. B6.

- ^ Scott, Jay (November 4, 1985). "Only the wrong survive in this dirty thriller". Globe and Mail. p. B6.

- ^ "Rushes". Time. April 18, 2005. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ The Digital Fix. Staff DVD review. December 7, 2003. Accessed: August 8, 2013.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (August 31, 2008). "The 25 best L.A. films of the last 25 years". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ^ ^ a b c Segaloff 1990, p. 226.

- ^ a b "Geffen Records Press Release For To Live and Die in L.A.". Geffen Records. September 1985. Archived from the original on 2008-03-12. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ Dreuth, Josh (December 10, 2009). "Fox February Titles Get Detailed". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ http://deadline.com/2015/06/to-live-and-die-in-la-tv-series-william-friedkin-wgn-america-1201456085/

Bibliography

- Segaloff, Nat (1990) Hurricane Billy: The Stormy Life and Films of William Friedkin. New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-688-07852-4.

External links

- 1985 films

- 1980s action thriller films

- 1980s crime thriller films

- American action thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American films

- Films based on thriller novels

- Chase films

- Films directed by William Friedkin

- Films set in Los Angeles, California

- American independent films

- Police detective films

- United Artists films

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films