Trypanosoma

- This article is about the genus Trypanosoma, for the specific human pathogens see Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi.

| Trypanosoma | |

|---|---|

| |

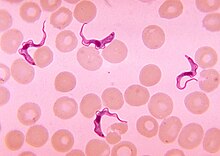

| Trypanosoma sp. among red blood cells. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Trypanosoma Gruby, 1843

|

Trypanosoma is a genus of kinetoplastids (class Kinetoplastida), a monophyletic[1] group of unicellular parasitic flagellate protozoa. The name is derived from the Greek trypano- (borer) and soma (body) because of their corkscrew-like motion. All trypanosomes are heteroxenous (requiring more than one obligatory host to complete life cycle) and most are transmitted via a vector. The majority of species are transmitted by blood-feeding invertebrates, but there are different mechanisms among the varying species. In an invertebrate host they are generally found in the intestine, but normally occupy the bloodstream or an intracellular environment in the mammalian host.

Trypanosomes infect a variety of hosts and cause various diseases, including the fatal human diseases sleeping sickness, caused by Trypanosoma brucei, and Chagas disease, caused by Trypanosoma cruzi.

The mitochondrial genome of the Trypanosoma, as well as of other kinetoplastids, known as the kinetoplast, is made up of a highly complex series of catenated circles and minicircles and requires a cohort of proteins for organisation during cell division.

History

The first species of Trypanosoma identified was in a trout by Valentin in 1841. They were identified in mammals 50–80 years later.

Taxonomy

The monophyly of the genus Trypanosoma is not supported by a number of different methods. Rather, the American and African trypanosomes constitute distinct clades, implying that the major human disease agents T. cruzi (cause of Chagas’ disease) and T. brucei (cause of African sleeping sickness) are not closely related to each other.[2]

Phylogenetic analyses suggest an ancient split into a branch containing all Salivarian trypanosomes and a branch containing all non-Salivarian lineages. The latter branch splits into a clade containing bird, reptilian and Stercorarian trypanosomes infecting mammals and a clade with a branch of fish trypanosomes and a branch of reptilian or amphibian lineages.[3]

Salivarians are trypanosomes of the subgenera of Duttonella, Trypanozoon, Pycnomonas and Nannomonas. These trypanosomes are passed to the recipient in the saliva of the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.).[4] Antigenic variation is a characteristic shared by the Salivaria, which has been particularly well-studied in T. brucei.[5] The Trypanozoon subgenus contains the species Trypanosoma brucei, T. rhodesiense and T. equiperdum. The sub genus Duttonella contains the species T. vivax. Nannomonas contains T. congolense.[6]

Stercorians are trypanosomes passed to the recipient in the feces of insects from the subfamily Triatominae (most importantly Triatoma infestans).[7] This group includes Trypanosoma cruzi, T. lewisi, T. melophagium, T. nabiasi, T. rangeli, T. theileri, T. theodori.[8] The sub genus Herpetosoma contains the species T. lewisi and the sub genus Schizotrypanum contains T. cruzi.[6]

Evolution

The relationships between the species have not been worked out to date. It has been suggested that T. evansi arose from a clone of T. equiperdum which lost its maxicircles.[9] It has also been proposed that T. evansi should be classified as a subspecies of T. brucei.[10]

Selected species

Species of Trypanosoma include the following:

- T. ambystomae. in amphibians

- T. antiquus, extinct (Fossil in Miocene amber)

- T. avium, which causes trypanosomiasis in birds

- T. boissoni, in elasmobranch

- T. brucei, which causes sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in cattle

- T. cruzi, which causes Chagas disease in humans

- T. congolense, which causes nagana in ruminant livestock, horses and a wide range of wildlife

- T. equinum, in South American horses, transmitted via Tabanidae,

- T. equiperdum, which causes dourine or covering sickness in horses and other Equidae, it can be spread through coitus.

- T. evansi, which causes one form of the disease surra in certain animals (a single case report of human infection in 2005 in India[11] was successfully treated with suramin[12])

- T. everetti, in birds

- T. hosei, in amphibians

- T. irwini, in koalas

- T. lewisi, in rats

- T. melophagium, in sheep, transmitted via Melophagus ovinus

- T. paddae, in birds

- T. parroti, in amphibians

- T. percae, in the species Perca fluviatilis

- T. rangeli, believed to be nonpathogenic to humans

- T. rotatorium, in amphibians

- T. rugosae, in amphibians

- T. sergenti, in amphibians

- T. simiae, which causes nagana in pigs. Its main reservoirs are warthogs and bush pigs

- T. sinipercae, in fishes

- T. suis, which causes a different form of surra

- T. theileri, a large trypanosome infecting ruminants

- T. triglae, in marine teleosts

- T. vivax, which causes the disease nagana, mainly in West Africa, although it has spread to South America[13]

Hosts, life cycle and morphologies

Two different types of trypanosomes exist, and their life cycles are different, the salivarian species and the stercorarian species.

Stercorarian trypanosomes infect the insect, most often the triatomid kissing bug, develop in its posterior gut and infective organisms are released in the feces and deposited on the skin of the host. The organism then penetrates and can disseminate throughout the body. Insects become infected when taking a blood meal.

Salivarian trypanosomes develop in the anterior gut of insects, most importantly the Tsetse fly, and infective organisms are inoculated into the host by the insect bite before it feeds.

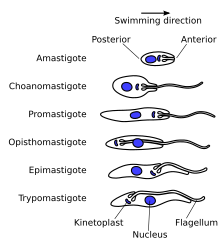

As trypanosomes progress through their life cycle they undergo a series of morphological changes as is typical of trypanosomatids. The life cycle often consists of the trypomastigote form in the vertebrate host and the trypomastigote or promastigote form in the gut of the invertebrate host. Intracellular lifecycle stages are normally found in the amastigote form. The trypomastigote morphology is unique to species in the genus Trypanosoma.

References

- ^ Hamilton PB, Stevens JR, Gaunt MW, Gidley J, Gibson WC (2004). "Trypanosomes are monophyletic: evidence from genes for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase and small subunit ribosomal RNA". Int. J. Parasitol. 34 (12): 1393–404. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.08.011. PMID 15542100.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Environmental kinetoplastid-like 18S rRNA sequences and phylogenetic relationships among Trypanosomatidae: Paraphyly of the genus Trypanosoma. Helen Piontkivska and Austin L. Hughes, Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, November 2005, Volume 144, Issue 1, Pages 94–99, doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.08.007

- ^ The molecular phylogeny of trypanosomes: evidence for an early divergence of the Salivaria. Jochen Haag, Colm O'hUigin and Peter Overath, Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 1 March 1998, Volume 91, Issue 1, Pages 37–49, doi:10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00185-0

- ^ Definition of the word Salivarian at medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com

- ^ Sex and evolution in trypanosomes. Wendy Gibson, International Journal for Parasitology, 1 May 2001, Volume 31, Issues 5–6, Pages 643–647, doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00138-2

- ^ a b Dihydrofolate reductases within the genus Trypanosoma. J.J. Jaffe, J.J. McCormack Jr and W.E. Gutteridge, Experimental Parasitology, 1969, Volume 25, Pages 311–318, doi:10.1016/0014-4894(69)90076-9

- ^ [1]

- ^ Stercoraria at medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com

- ^ Brun R, Hecker H, Lun ZR (1998) Trypanosoma evansi and T. equiperdum: distribution, biology, treatment and phylogenetic relationship (a review). Vet Parasitol 79(2):95-107

- ^ Carnes J, Anupama A, Balmer O, Jackson A, Lewis M, Brown R, Cestari I, Desquesnes M, Gendrin C, Hertz-Fowler C, Imamura H, Ivens A, Kořený L, Lai DH, MacLeod A, McDermott SM, Merritt C, Monnerat S, Moon W, Myler P, Phan I, Ramasamy G, Sivam D, Lun ZR, Lukeš J, Stuart K, Schnaufer A (2015) Genome and phylogenetic analyses of Trypanosoma evansi reveal extensive similarity to T. brucei and multiple independent origins for dyskinetoplasty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9(1):e3404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003404

- ^ World Health, Organization (2005). "A new form of human trypanosomiasis in India. Description of the first human case in the world caused by Trypanosoma evansi". Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 80 (7): 62–3. PMID 15771199.

- ^ Joshi PP, Chaudhari A, Shegokar VR; et al. (2006). "Treatment and follow-up of the first case of human trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma evansi in India". Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 100 (10): 989–91. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.11.003. PMID 16455122.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Batista JS, Rodrigues CM, García HA, Bezerra FS, Olinda RG, Teixeira MM, Soto-Blanco B. (2011). "Association of Trypanosoma vivax in extracellular sites with central nervous system lesions and changes in cerebrospinal fluid in experimentally infected goats". Veterinary Research. 42 (63): 1–7. doi:10.1186/1297-9716-42-63. PMC 3105954. PMID 21569364.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

External links

- Trypanosoma reviewed and published by Wikivet, accessed 08/10/2011.

- Trykipedia, Trypanosomatid specific ontologies

- Tree of Life: Trypanosoma