Worry

Worry refers to the thoughts, images and emotions of a negative nature in which mental attempts are made[vague] to avoid anticipated potential threats.[1] As an emotion it is experienced as anxiety or concern about a real or imagined issue, often personal issues such as health or finances, or broader issues such as environmental pollution and social or technological change. Most people experience short-lived periods of worry in their lives without incident; indeed, a moderate amount of worrying may even have positive effects, if it prompts people to take precautions (e.g., fastening their seat belt or buying fire insurance) or avoid risky behaviours (e.g., angering dangerous animals, or binge drinking).

Excessive worry is the main component of generalized anxiety disorder.

Theories

Dr. Edward Hallowell, psychiatrist and author of Worry," argues that while "Worry serves a productive function," anticipatory and dangerous worrying—which he calls "toxic worry"—can be harmful for your mental and physical health. He claims that "Toxic worry is when the worry paralyzes you," whereas "Good worry leads to constructive action" such as taking steps to resolve the issue that is causing concern. To combat worry, Hallowell suggests that people should not worry alone, because people are much more likely to come up with solutions when talking about their concerns with a friend. As well, he urges worriers to find out more information about the issue that is troubling them, or make sure that their information is correct. Another step to reduce worry is to make a plan and take action and take "care of your brain" by sleeping enough, getting exercise, and eating a healthy diet (without a "lot of carbs, junk food, alcohol, drugs, etc). Hallowell encourages worriers to get "regular doses of positive human contact" such as "a hug or a warm pat on the back." Finally, he suggests that worriers let the problem go rather than gathering them around themselves.[3]

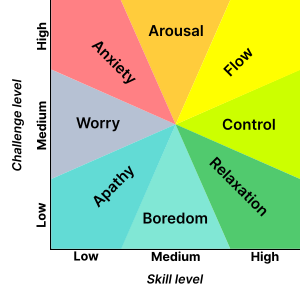

In positive psychology, worry is described as a response to a moderate challenge for which the subject has inadequate skills.[2]

In scientific psychology, worry is part of Perseverative Cognition (a collective term for continuous thinking about negative events in the past or in the future).[4]

Meher Baba stated that worry is caused by desires and can be overcome through detachment: "Worry is the product of feverish imagination working under the stimulus of desires....[It] is a necessary resultant of attachment to the past or to the anticipated future, and it always persists in some form or other until the mind is completely detached from everything."[5]

See also

References

- ^ Borkovec TD. (2002). Living in a state of worry can cause anxiety, and depression, as well as ruin the present. "Worry does take the pain out of tomorrow, it causes one to be prepared today." -Anonymous. Life in the future versus life in the present. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9, 76–80.

- ^ a b Csikszentmihalyi M (1997). Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life (1st ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-465-02411-7. Cite error: The named reference "Finding Flow" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ 5 steps to control worry

- ^ Brosschot, J.F., Pieper, S. & Thayer J.F. (2005) Expanding Stress Theory: Prolonged Activation And Perseverative Cognition. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(10):1043-9.

- ^ Baba, Meher (1967). Discourses. 3. Sufism Reoriented. pp. 121-22. ISBN 978-1880619094.