Proso millet: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Correct, expand. |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Panicum miliaceum''''' is a grain crop with many [[common name]]s, including '''proso millet''', '''broomcorn millet''', '''common millet''', '''hog millet''', '''Kashfi millet''', '''red millet''', and '''white millet'''.<ref name=GRIN>{{GRIN | access-date=8 January 2015}}</ref> [[Archaeobotany|Archaeobotanical]] evidence suggests millet was first domesticated about [[Before Present|10,000 BP]] in Northern China.<ref name=domestication>{{ |

'''''Panicum miliaceum''''' is a grain crop with many [[common name]]s, including '''proso millet''', '''broomcorn millet''', '''common millet''', '''hog millet''', '''Kashfi millet''', '''red millet''', and '''white millet'''.<ref name=GRIN>{{GRIN | access-date=8 January 2015}}</ref> [[Archaeobotany|Archaeobotanical]] evidence suggests millet was first domesticated about [[Before Present|10,000 BP]] in Northern China.<ref name = domestication > {{ Cite journal | doi-access = free | last1 = Lu | first1 = H. | last2 = Zhang | first2 = J. | last3 = Liu | first3 = K.-b. | last4 = Wu | first4 = N. | last5 = Li | first5 = Y. | last6 = Zhou | first6 = K. | last7 = Ye | first7 = M. | last8 = Zhang | first8 = T. | last9 = Zhang | first9 = H. | last10 = Yang | first10 = X. | last11 = Shen | first11 = L. | last12 = Xu | first12 = D. | last13 = Li | first13 = Q. | journal = [[Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences]] (PNAS) | title = Earliest domestication of common millet (''Panicum miliaceum'') in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago | date = 21 April 2009 | volume = 106 | issue = 18 | pages = 7367–7372 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0900158106 | pmid = 19383791 | pmc = 2678631 | bibcode = 2009PNAS..106.7367L }}</ref> The crop is extensively cultivated in [[Agriculture in China|China]], [[Agriculture in India|India]], [[Agriculture in Nepal|Nepal]], [[Agriculture in Russia|Russia]], [[Agriculture in Ukraine|Ukraine]], [[Agriculture in Belarus|Belarus]], the [[Middle East]], [[Agriculture in Turkey|Turkey]], [[Agriculture in Romania|Romania]], and the [[Agriculture in the United States|United States]], where about half a million acres are grown each year.<ref>{{Cite web|url= https://www.nass.usda.gov/ |title = USDA - National Agricultural Statistics Service Homepage}}</ref>{{Better source needed|date=September 2022}} The crop is notable both for its extremely short lifecycle, with some varieties producing grain only 60 days after planting,<ref name=waxymilletpaper>{{cite journal |last1=Graybosch |first1=R. A. |last2=Baltensperger |first2=D. D. |title=Evaluation of the waxy endosperm trait in proso millet|journal=Plant Breeding |date=February 2009 |volume=128 |issue=1 |pages=70–73 |doi=10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01511.x|url= http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1367&context=agronomyfacpub }}</ref> and its low water requirements, producing grain more efficiently per unit of moisture than any other grain species tested.<ref name=waxymilletpaper/><ref>{{cite book|author1=Lyman James Briggs|author2=Homer LeRoy Shantz|title=The water requirement of plants|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=rkIZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR29 |year=1913|publisher=Govt. Print. Off.|pages=29–}}</ref> The name "proso millet" comes from the pan-Slavic general and generic name for millet ({{lang-sh-Latn-Cyrl|separator=/|proso|просо}}, {{lang-cs|proso}}, {{lang-pl|proso}}, {{lang-ru|просо}}). Proso millet is a relative of [[foxtail millet]], [[pearl millet]], [[maize]], and [[sorghum]] within the grass subfamily [[Panicoideae]]. While all of these crops use [[C4 photosynthesis]], the others all employ the NADP-ME as their primary carbon shuttle pathway, while the primary C4 carbon shuttle in proso millet is the NAD-ME pathway. |

||

==Evolutionary history== |

== Evolutionary history == |

||

''Panicum miliaceum'' is a tetraploid species with a base chromosome number of 18, twice the base chromosome number of diploid species within |

''Panicum miliaceum'' is a [[tetraploid]] species with a base chromosome number of 18, twice the base chromosome number of [[diploid]] species within its genus ''[[Panicum]]''.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Aliscioni |first1=Sandra S. |last2=Giussani |first2=Liliana M. |last3=Zuloaga |first3=Fernando O. |last4=Kellogg |first4=Elizabeth A. |title=A molecular phylogeny of ''Panicum'' (Poaceae: Paniceae): tests of monophyly and phylogenetic placement within the Panicoideae |journal= [[American Journal of Botany]] |date=May 2003 |volume=90 |issue=5 |pages=796–821 |doi=10.3732/ajb.90.5.796 |pmid=21659176}}</ref> The species appears to be an [[allotetraploid]] resulting from a wide hybrid between two different diploid ancestors.<ref name=reticulateevolution>{{cite journal |last1=Hunt |first1=H. V. |last2=Badakshi |first2=F. |last3=Romanova |first3=O. |last4=Howe |first4=C. J. |last5=Jones |first5=M. K. |last6=Heslop-Harrison |first6=J. S. P. |display-authors=3|title=Reticulate evolution in ''Panicum'' (Poaceae): the origin of tetraploid broomcorn millet, ''P. miliaceum'' |journal= [[Journal of Experimental Botany]] (JxB) |date=10 April 2014 |volume=65 |issue=12 |pages=3165–3175 |doi=10.1093/jxb/eru161|pmid=24723408 |pmc=4071833 }}</ref> One of the two subgenomes within proso millet appears to have come from either ''[[Panicum capillare/P. capillare]]'' or a close relative of that species. The second subgenome does not show close homology to any known diploid ''Panicum'' species, but some unknown diploid ancestor apparently also contributed a copy of its genome to a separate [[allotetraploid]] species ''[[Panicum repens|P. repens]]'' (torpedo grass).<ref name=reticulateevolution/> The two subgenomes within proso millet are estimated to have diverged 5.6 million years ago.<ref name=prosogenome>{{cite journal |last1=Zou |first1=Changsong |last2=Li |first2=Leiting |last3=Miki |first3=Daisuke |last4=Li |first4=Delin |last5=Tang |first5=Qiming |last6=Xiao |first6=Lihong |last7=Rajput |first7=Santosh |last8=Deng |first8=Ping |last9=Peng |first9=Li |last10=Jia |first10=Wei |last11=Huang |first11=Ru |last12=Zhang |first12=Meiling |last13=Sun |first13=Yidan |last14=Hu |first14=Jiamin |last15=Fu |first15=Xing |last16=Schnable |first16=Patrick S. |last17=Chang |first17=Yuxiao |last18=Li |first18=Feng |last19=Zhang |first19=Hui |last20=Feng |first20=Baili |last21=Zhu |first21=Xinguang |last22=Liu |first22=Renyi |last23=Schnable |first23=James C. |last24=Zhu |first24=Jian-Kang |last25=Zhang |first25=Heng |display-authors=3|title=The genome of broomcorn millet |journal= [[Nature Communications]] |date=25 January 2019 |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=436 |doi=10.1038/s41467-019-08409-5|pmid=30683860 |pmc=6347628 |bibcode=2019NatCo..10..436Z }}</ref> However, the species has experienced only limited amounts of fractionation and copies of most genes are still retained on both subgenomes.<ref name=prosogenome /> A sequenced version of the proso millet genome, estimated to be around 920 [[megabase]] pairs in size, was published in 2019.<ref name=prosogenome /> |

||

==Domestication and history of cultivation== |

== Domestication and history of cultivation == |

||

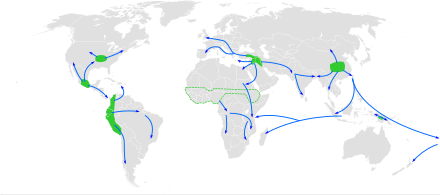

[[File:Centres of origin and spread of agriculture.svg|thumb|right|upright=2.0|Map of the world showing approximate centers of origin of agriculture and its spread in prehistory: the Fertile Crescent (11,000 BP), the Yangtze and Yellow River basins (9,000 BP), the New Guinea Highlands (9,000–6,000 BP), Central Mexico (5,000–4,000 BP), Northern South America (5,000–4,000 BP), sub-Saharan Africa (5,000–4,000 BP, exact location unknown), and eastern North America (4,000–3,000 BP).<ref>{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1126/science.1078208 | last1 = Diamond | first1 = J. | last2 = Bellwood | first2 = P. | title = Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions | journal = Science | volume = 300 | issue = 5619 | pages = 597–603 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12714734|bibcode = 2003Sci...300..597D | url = http://faculty.bennington.edu/%7Ekwoods/classes/enviro-hist/diamond%20agriculture%20and%20language.pdf | citeseerx = 10.1.1.1013.4523 | s2cid = 13350469 }}</ref>]] |

[[File:Centres of origin and spread of agriculture.svg|thumb|right|upright=2.0|Map of the world showing approximate centers of origin of agriculture and its spread in prehistory: the Fertile Crescent (11,000 BP), the Yangtze and Yellow River basins (9,000 BP), the New Guinea Highlands (9,000–6,000 BP), Central Mexico (5,000–4,000 BP), Northern South America (5,000–4,000 BP), sub-Saharan Africa (5,000–4,000 BP, exact location unknown), and eastern North America (4,000–3,000 BP).<ref>{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1126/science.1078208 | last1 = Diamond | first1 = J. | last2 = Bellwood | first2 = P. | title = Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions | journal = Science | volume = 300 | issue = 5619 | pages = 597–603 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12714734|bibcode = 2003Sci...300..597D | url = http://faculty.bennington.edu/%7Ekwoods/classes/enviro-hist/diamond%20agriculture%20and%20language.pdf | citeseerx = 10.1.1.1013.4523 | s2cid = 13350469 }}</ref>]] |

||

Weedy forms of proso millet are found throughout central Asia, covering a widespread area from the [[Caspian Sea]] east to [[Xinjiang]] and [[Mongolia]]. These may represent the wild progenitor of proso millet or feral escapes from domesticated production.<ref name="ZH">{{cite book |title=Domestication of Plants in the Old World |editor-first1=Daniel |editor-last1=Zohary |editor-first2=Maria |editor-last2=Hopf |edition=3rd |publisher= Oxford University Press |year=2000|isbn= 978-0198503569}}</ref>{{rp|83}} Indeed, in the United States, weedy proso millet, representing feral escapes from cultivation, are now common, suggesting current proso millet cultivars retain the potential to revert, similar to the pattern seen for weedy rice.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Thurber |first1=Carrie S. |last2=Reagon |first2=Michael |last3=Gross |first3=Briana L. |last4=Olsen |first4=Kenneth M. |last5=Jia |first5=Yulin |last6=CAICEDO |first6=ANA L. |display-authors=3|title=Molecular evolution of shattering loci in U.S. weedy rice |journal=Molecular Ecology |date=August 2010 |volume=19 |issue=16 |pages=3271–3284 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04708.x|pmid=20584132 |pmc=2988683 }}</ref> Currently, the earliest archeological evidence for domesticated proso millet comes from the Cishan site in semiarid north east China around 8,000 BCE.<ref name=domestication/> Because early varieties of proso millet had such a short lifecycle, as little as 45 days from planting to harvest, they are thought to have made it possible for seminomadic tribes to first adopt agriculture, forming a bridge between hunter-gatherer-focused lifestyles and early agricultural civilizations.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/this-ancient-grain-may-have-helped-humans-become-farmers-180957546/ |title = This Ancient Grain May Have Helped Humans Become Farmers|first=Maris |last=Fessenden |date=January 7, 2016|publisher=Smithsonian Magazine}}</ref> Archaeological evidence for cultivation of domesticated proso millet in east Asia and Europe dates to at least 5,000 BCE in [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]] and Germany (near Leipzig, Hadersleben) by [[Linear Pottery culture]] (Early LBK, Neolithikum 5500–4900 BCE),<ref>{{cite book |first=Udelgard |last=Körber-Grohne |title=Nutzpflanzen in Deutschland: Kulturgeschichte und Biologie |editor=Verlag Theiss |year=1987 |language=de |isbn=3-8062-0481-0}}</ref> and may represent either an independent domestication of the same wild ancestor, or the spread of the crop from east Asia along trade routes through the arid steppes.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hunt |first1=H. V. |last2=Badakshi |first2=F. |last3=Romanova |first3=O. |last4=Howe |first4=C. J. |last5=Jones |first5=M. K. |last6=Heslop-Harrison |first6=J. S. P. |display-authors=3|title=Reticulate evolution in Panicum (Poaceae): the origin of tetraploid broomcorn millet, P. miliaceum |journal=Journal of Experimental Botany |date=10 April 2014 |volume=65 |issue=12 |pages=3165–3175 |doi=10.1093/jxb/eru161|pmid=24723408 |pmc=4071833 }}</ref> Evidence for cultivation in southern Europe and the Near East is comparatively more recent, with the earliest evidence for its cultivation in the Near East a find in the ruins of [[Nimrud|Nimrud, Iraq]], dated to about 700 BC.<ref name="ZH"/>{{rp|86}} |

Weedy forms of proso millet are found throughout central Asia, covering a widespread area from the [[Caspian Sea]] east to [[Xinjiang]] and [[Mongolia]]. These may represent the wild progenitor of proso millet or feral escapes from domesticated production.<ref name="ZH">{{cite book |title=Domestication of Plants in the Old World |editor-first1=Daniel |editor-last1=Zohary |editor-first2=Maria |editor-last2=Hopf |edition=3rd |publisher= [[Oxford University Press]] (OUP) |year=2000|isbn= 978-0198503569}}</ref>{{rp|83}} Indeed, in the United States, weedy proso millet, representing feral escapes from cultivation, are now common, suggesting current proso millet cultivars retain the potential to revert, similar to the pattern seen for weedy rice.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Thurber |first1=Carrie S. |last2=Reagon |first2=Michael |last3=Gross |first3=Briana L. |last4=Olsen |first4=Kenneth M. |last5=Jia |first5=Yulin |last6=CAICEDO |first6=ANA L. |display-authors=3|title=Molecular evolution of shattering loci in U.S. weedy rice |journal= [[Molecular Ecology]] |date=August 2010 |volume=19 |issue=16 |pages=3271–3284 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04708.x|pmid=20584132 |pmc=2988683 }}</ref> Currently, the earliest archeological evidence for domesticated proso millet comes from the Cishan site in semiarid north east China around 8,000 BCE.<ref name=domestication/> Because early varieties of proso millet had such a short lifecycle, as little as 45 days from planting to harvest, they are thought to have made it possible for seminomadic tribes to first adopt agriculture, forming a bridge between hunter-gatherer-focused lifestyles and early agricultural civilizations.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/this-ancient-grain-may-have-helped-humans-become-farmers-180957546/ |title = This Ancient Grain May Have Helped Humans Become Farmers|first=Maris |last=Fessenden |date=January 7, 2016|publisher=Smithsonian Magazine}}</ref> Archaeological evidence for cultivation of domesticated proso millet in east Asia and Europe dates to at least 5,000 BCE in [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]] and Germany (near Leipzig, Hadersleben) by [[Linear Pottery culture]] (Early LBK, Neolithikum 5500–4900 BCE),<ref>{{cite book |first=Udelgard |last=Körber-Grohne |title=Nutzpflanzen in Deutschland: Kulturgeschichte und Biologie |editor= [[Verlag Theiss]] |year=1987 |language=de |isbn=3-8062-0481-0}}</ref> and may represent either an independent domestication of the same wild ancestor, or the spread of the crop from east Asia along trade routes through the arid steppes.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hunt |first1=H. V. |last2=Badakshi |first2=F. |last3=Romanova |first3=O. |last4=Howe |first4=C. J. |last5=Jones |first5=M. K. |last6=Heslop-Harrison |first6=J. S. P. |display-authors=3|title= Reticulate evolution in ''Panicum'' (Poaceae): the origin of tetraploid broomcorn millet, ''P. miliaceum'' |journal= [[Journal of Experimental Botany]] (JxB) |date=10 April 2014 |volume=65 |issue=12 |pages=3165–3175 |doi=10.1093/jxb/eru161|pmid=24723408 |pmc=4071833 }}</ref> Evidence for cultivation in southern Europe and the Near East is comparatively more recent, with the earliest evidence for its cultivation in the Near East a find in the ruins of [[Nimrud|Nimrud, Iraq]], dated to about 700 BC.<ref name="ZH"/>{{rp|86}} |

||

==Cultivation== |

== Cultivation == |

||

Proso millet is a relatively low-demanding crop, and diseases are not known; consequently, it is often used in organic farming systems in Europe. In the United States, it is often used as an intercrop. Thus, proso millet can help to avoid a summer fallow, and continuous crop rotation can be achieved. Its superficial root system and its resistance to atrazine residue make proso millet a good intercrop between two water- and [[pesticide]]-demanding crops. The stubbles of the last crop, by allowing more heat into the soil, result in a faster and earlier millet growth. While millet occupies the ground, because of its superficial root system, the soil can replenish its water content for the next crop. Later crops, for example, a winter wheat, can in turn benefit from the millet stubble, which act as snow accumulators.<ref name="UNebraskaL">[http://ianrpubs.unl.edu/epublic/live/ec137/build/ec137.pdf Producing and marketing proso millet in the great plains], U. Nebraska-Lincoln Extension</ref> |

Proso millet is a relatively low-demanding crop, and diseases are not known; consequently, it is often used in organic farming systems in Europe. In the United States, it is often used as an intercrop. Thus, proso millet can help to avoid a summer fallow, and continuous crop rotation can be achieved. Its superficial root system and its resistance to atrazine residue make proso millet a good intercrop between two water- and [[pesticide]]-demanding crops. The stubbles of the last crop, by allowing more heat into the soil, result in a faster and earlier millet growth. While millet occupies the ground, because of its superficial root system, the soil can replenish its water content for the next crop. Later crops, for example, a winter wheat, can in turn benefit from the millet stubble, which act as snow accumulators.<ref name="UNebraskaL">[http://ianrpubs.unl.edu/epublic/live/ec137/build/ec137.pdf Producing and marketing proso millet in the great plains], U. Nebraska-Lincoln Extension</ref> ''P. miliaceum'' is commonly classified into five [[race (biology)|race]]s, ''miliaceum'', ''patentissimum'', ''contractum'', ''compactum'', and ''ovatum''.<ref name = "Diversity-Resources"> {{ Cite journal | volume = 6 | year = 2015 | publisher = [[Frontiers Media SA]] | first2 = Manish | first1 = Travis | last2 = Raizada | last1 = Goron | journal = [[Frontiers in Plant Science]] | issn = 1664-462X | title = Genetic diversity and genomic resources available for the small millet crops to accelerate a New Green Revolution | doi = 10.3389/fpls.2015.00157 }} </ref> |

||

===Climate and soil requirements=== |

=== Climate and soil requirements === |

||

Due to its C4 photosynthetic system, proso millet is thermophilic like [[maize]], so shady locations of the field should be avoided. It is sensitive to temperatures lower than 10 to 13 |

Due to its C4 photosynthetic system, proso millet is thermophilic like [[maize]], so shady locations of the field should be avoided. It is sensitive to temperatures lower than {{ Convert | 10 to 13 | C }}. Proso millet is highly drought-resistant, which makes it of interest to regions with low water availability and longer periods without rain.<ref name="Biohirse">Merkblatt für den Anbau von Rispenhirse im biologischen Landbau, www.biofarm.ch, http://www.biofarm.ch/assets/files/Landwirtschaft/Merkblatt_Biohirse_Version%2012_2010.pdf(23.11.14) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150203161307/http://www.biofarm.ch/assets/files/Landwirtschaft/Merkblatt_Biohirse_Version%2012_2010.pdf |date=2015-02-03 }}</ref><ref name="Pearl">{{cite book |vauthors= Hanna WW, Baltensperger DD, Seetharam A |year=2004 |chapter=Pearl Millet and Other Millets |title=Warm-Season (C4) Grasses |series= [[Agronomy Monographs]] |pages=537–560 |veditors=Moser LE, Burson BL, Sollenberger LE |doi=10.2134/agronmonogr45.c15|isbn=9780891182375 }}</ref> The soil should be light or medium-heavy. Due to its flat root systems, soil compaction must be avoided. Furthermore, proso millet does not tolerate soil wetness caused by dammed-up water.<ref name="Pearl" /> |

||

===Seedbed and sowing === |

=== Seedbed and sowing === |

||

The seedbed should be finely crumbled as for [[sugar beet]] and [[rapeseed]].<ref name=Biohirse /> In Europe, proso millet is sowed between mid-April and the end of May. About 500 g/acre of seeds are required, which is roughly 500 |

The seedbed should be finely crumbled as for [[sugar beet]] and [[rapeseed]].<ref name=Biohirse /> In Europe, proso millet is sowed between mid-April and the end of May. About {{ Convert | 500 | g/acre }} of seeds are required, which is roughly {{ Convert | 500 | /m2 | /acre }}. In [[organic farming]], this amount should be increased if a [[harrow (tool)|harrow]] weeder is used. For sowing, the usual sowing machines can be used similarly to how they are used for other crops such as wheat. A distance between the rows of {{ Convert | 16 to 25 | cm }} is recommended if the farmer uses an interrow [[cultivator]]. The sowing depth should be {{ Convert | 1.5 to 2 | cm }} in optimal soil or {{ Convert | 3 to 4 | cm }} in dry soil. Rolling of the ground after sowing is helpful for further cultivation.<ref name=Biohirse /> Cultivation in [[no-till farming]] systems is also possible and often practiced in the United States. Sowing then can be done two weeks later.<ref name="UNebraskaL"/> |

||

[[File:White Proso Millet.jpg|thumb|White proso millet]] |

[[File:White Proso Millet.jpg|thumb|White proso millet]] |

||

===Field management=== |

=== Field management === |

||

Only a few diseases and pests are known to attack proso millet, but they are not economically important. Weeds are a bigger problem. The critical phase is in juvenile development. The formation of the grains happens in the 3- to 5-leaf |

Only a few diseases and pests are known to attack proso millet, but they are not economically important. Weeds are a bigger problem. The critical phase is in juvenile development. The formation of the grains happens in the 3- to 5-leaf stage. After that, all nutrients should be available for the millet, so preventing the growth of weeds is necessary. In [[conventional farming]], [[herbicides]] may be used. In [[organic farming]], harrow weeder or interrow [[cultivator]] use is possible, but special sowing parameters are needed.<ref name=Biohirse /> |

||

For good crop development, [[fertilization]] with 50 to 75 |

For good crop development, [[fertilization]] with {{ Convert | 50 to 75 | kg }} nitrogen per hectare is recommended.<ref name="Pearl" /> Planting proso millet in a [[crop rotation]] after [[maize]] should be avoided due to its same weed spectrum. Because proso millet is an undemanding crop, it may be used at the end of the [[crop rotation|rotation]].<ref name=Biohirse /> |

||

===Harvesting and postharvest treatments=== |

=== Harvesting and postharvest treatments === |

||

Harvest time is at the end of August until mid-September. Determining the best harvest date is not easy because all the grains do not ripen simultaneously. The grains on the top of the [[panicle]] ripen first, while the grains in the lower parts need more time, making compromise and harvest necessary to optimize yield.<ref name=Biohirse /> Harvesting can be done with a conventional [[combine harvester]] with the moisture content of the grains around 15-20%. Usually, proso millet is mowed into [[windrow]]s first, since the plants are not dry like [[wheat]]. There, they can wither, which makes the [[threshing]] easier. Then the harvest is done with a pickup attached to a combine.<ref name=Biohirse /> |

Harvest time is at the end of August until mid-September. Determining the best harvest date is not easy because all the grains do not ripen simultaneously. The grains on the top of the [[panicle]] ripen first, while the grains in the lower parts need more time, making compromise and harvest necessary to optimize yield.<ref name=Biohirse /> Harvesting can be done with a conventional [[combine harvester]] with the moisture content of the grains around 15-20%. Usually, proso millet is mowed into [[windrow]]s first, since the plants are not dry like [[wheat]]. There, they can wither, which makes the [[threshing]] easier. Then the harvest is done with a pickup attached to a combine.<ref name=Biohirse /> |

||

Possible yields are between 2.5 and 4.5 |

Possible yields are between {{ Convert | 2.5 and 4.5 | t/ha }} under optimal conditions. Studies in Germany showed that even higher yields can be attained.<ref name=Biohirse /> |

||

===United States=== |

===United States=== |

||

About half of the millet grown in the United States is grown in eastern Colorado on 340,000 |

About half of the millet grown in the United States is grown in eastern Colorado on {{ Convert | 340,000 | acre )). Historically grown as animal and bird seed, as of 2020, it has found a market as an organic gluten-free grain.<ref name="DP73020">{{cite news |author1=Daliah Singer |title=Colorado's hottest grain is gluten-free, nutrient-dense, great in beer and about to be your new fav pantry staple Colorado produces the most millet in the country. But what exactly is it? |url=https://theknow.denverpost.com/2020/07/30/millet-grain-colorado/242449/ |access-date=July 30, 2020 |work=The Denver Post |date=July 30, 2020}}</ref> |

||

==Uses== |

== Uses == |

||

[[File:Gijang-bap.jpg|thumb|''Gijang-[[bap (rice dish)|bap]]'' (proso millet rice)]] |

[[File:Gijang-bap.jpg|thumb|''Gijang-[[bap (rice dish)|bap]]'' (proso millet rice)]] |

||

{{Infobox nutritional value |

{{Infobox nutritional value |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

| right=1}} |

| right=1}} |

||

Proso millet is one of the few types of millet not cultivated in Africa.<ref>{{cite book |author=National Research Council |title=Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains |url=http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2305&page=260 |access-date=2008-07-18 |series=Lost Crops of Africa |volume=1 |date=1996-02-14 |publisher=National Academies Press |isbn=978-0-309-04990-0 |doi= 10.17226/2305|page=260 |chapter=Ebony |chapter-url=http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2305&page=252 }}</ref> |

Proso millet is one of the few types of millet not cultivated in Africa.<ref>{{cite book |author=National Research Council |title=Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains |url=http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2305&page=260 |access-date=2008-07-18 |series= [[Lost Crops of Africa]] |volume=1 |date=1996-02-14 |publisher= [[National Academies Press]] (NAP) |isbn=978-0-309-04990-0 |doi= 10.17226/2305|page=260 |chapter=Ebony |chapter-url=http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2305&page=252 }}</ref> |

||

In the United States, former Soviet Union, and some South American countries, it is primarily grown for livestock feed. As a grain fodder, it is very deficient in [[lysine]] and needs complementation. |

In the United States, former Soviet Union, and some South American countries, it is primarily grown for livestock feed. As a grain fodder, it is very deficient in [[lysine]] and needs complementation. |

||

Proso millet is also a poor fodder due to its low leaf-to-stem ratio and a possible irritant effect due to its hairy stem. Foxtail millet, having a higher leaf-to-stem ratio and less hairy stems, is preferred as fodder, particularly the variety called moha, which is a high-quality fodder. |

Proso millet is also a poor fodder due to its low leaf-to-stem ratio and a possible irritant effect due to its hairy stem. Foxtail millet, having a higher leaf-to-stem ratio and less hairy stems, is preferred as fodder, particularly the variety called moha, which is a high-quality fodder. |

||

To promote millet cultivation, other potential uses have been considered recently.<ref name="Rose">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rose DJ, Santra DK |year=2013 |title=Proso millet (''Panicum miliaceum'' L.) fermentation for fuel ethanol production |journal=Industrial Crops and Products |volume=43 |issue=1 |pages=602–605 |doi=10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.08.010|s2cid=1627015 |url=http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1066&context=panhandleresext }}</ref> For example, [[starch]] derived from millets has been shown to be a good substrate for fermentation and malting with grains having similar starch contents as wheat grains.<ref name="Rose"/> A recently published study suggested that starch derived from proso millet can be converted to [[ethanol]] with an only moderately lower efficiency than starch derived from corn.<ref name="Taylor">{{cite journal | last1 = Taylor | first1 = J.R.N. | last2 = Schober | first2 = T.J. | last3 = Bean | first3 = S.R. | year = 2006 | title = Novel food and non-food uses for sorghum and millets | journal = Journal of Cereal Science | volume = 44 | issue = 3| pages = 252–271 | doi=10.1016/j.jcs.2006.06.009}}</ref> The development of varieties with highly fermentable characteristics could improve ethanol yield to that of highly fermentable corn.<ref name="Taylor"/> Since proso millet is compatible with low-input agriculture, cultivation on marginal soils for biofuel production could represent an important new market, such as for farmers in the High Plains of the US.<ref name="Taylor"/> |

To promote millet cultivation, other potential uses have been considered recently.<ref name="Rose">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rose DJ, Santra DK |year=2013 |title=Proso millet (''Panicum miliaceum'' L.) fermentation for fuel ethanol production |journal= [[Industrial Crops and Products]] |volume=43 |issue=1 |pages=602–605 |doi=10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.08.010|s2cid=1627015 |url=http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1066&context=panhandleresext }}</ref> For example, [[starch]] derived from millets has been shown to be a good substrate for fermentation and malting with grains having similar starch contents as wheat grains.<ref name="Rose"/> A recently published study suggested that starch derived from proso millet can be converted to [[ethanol]] with an only moderately lower efficiency than starch derived from corn.<ref name="Taylor">{{cite journal | last1 = Taylor | first1 = J.R.N. | last2 = Schober | first2 = T.J. | last3 = Bean | first3 = S.R. | year = 2006 | title = Novel food and non-food uses for sorghum and millets | journal = [[Journal of Cereal Science]] | volume = 44 | issue = 3| pages = 252–271 | doi=10.1016/j.jcs.2006.06.009}}</ref> The development of varieties with highly fermentable characteristics could improve ethanol yield to that of highly fermentable corn.<ref name="Taylor"/> Since proso millet is compatible with low-input agriculture, cultivation on marginal soils for biofuel production could represent an important new market, such as for farmers in the High Plains of the US.<ref name="Taylor"/> |

||

The demand for more diverse and healthier cereal-based foods is increasing, particularly in affluent countries.<ref name="Saleh">{{cite journal |vauthors=Saleh AS, Zhang Q, Chen J, Shen Q |year=2012 |title=Millet Grains: Nutritional Quality, Processing, and Potential Health Benefits |journal=Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety |volume=12 |issue=3 |pages=281–295 |doi=10.1111/1541-4337.12012|s2cid=86749886 }}</ref> This could create new markets for proso millet products in human nutrition. Protein content in proso millet grains is comparable with that of wheat, but the share of some essential amino acids ([[leucine]], [[isoleucine]], and [[methionine]]) is substantially higher in proso millet.<ref name="Saleh"/> In addition, health-promoting phenolic compounds contained in the grains are readily bioaccessible, and their high [[calcium]] content favors bone strengthening and dental health.<ref name="Saleh"/> Among the most commonly consumed products are ready-to-eat breakfast cereals made purely from millet flour,<ref name="Biohirse"/><ref name="Saleh"/> and a variety of noodles and bakery products that are, however, often produced from mixtures with wheat flour to improve their sensory quality.<ref name="Saleh"/> |

The demand for more diverse and healthier cereal-based foods is increasing, particularly in affluent countries.<ref name="Saleh">{{cite journal |vauthors=Saleh AS, Zhang Q, Chen J, Shen Q |year=2012 |title=Millet Grains: Nutritional Quality, Processing, and Potential Health Benefits |journal= [[Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety]] |volume=12 |issue=3 |pages=281–295 |doi=10.1111/1541-4337.12012|s2cid=86749886 }}</ref> This could create new markets for proso millet products in human nutrition. Protein content in proso millet grains is comparable with that of wheat, but the share of some essential amino acids ([[leucine]], [[isoleucine]], and [[methionine]]) is substantially higher in proso millet.<ref name="Saleh"/> In addition, health-promoting phenolic compounds contained in the grains are readily bioaccessible, and their high [[calcium]] content favors bone strengthening and dental health.<ref name="Saleh"/> Among the most commonly consumed products are ready-to-eat breakfast cereals made purely from millet flour,<ref name="Biohirse"/><ref name="Saleh"/> and a variety of noodles and bakery products that are, however, often produced from mixtures with wheat flour to improve their sensory quality.<ref name="Saleh"/> |

||

==Pests== |

==Pests== |

||

Insect |

[[Insect pest]]s include:<ref name="Kalaisekar">{{cite book|last=Kalaisekar|first=A|title=Insect pests of millets: systematics, bionomics, and management|publisher= [[Elsevier]] |publication-place= [[London]] |year=2017|isbn=978-0-12-804243-4|oclc=967265246}}</ref> |

||

;Seedling pests |

;Seedling pests |

||

*shoot fly ''[[Atherigona pulla]]'' (proso millet shoot fly,<ref>Ravulapenta Sathish, M Manjunatha, K Rajashekarappa. [https://www.entomoljournal.com/archives/?year=2017&vol=5&issue=5&ArticleId=2557 Incidence of shoot fly, ''Atherigona pulla'' (Wiedemann) on proso millet at different dates of sowing]. ''J Entomol Zool Stud'' 2017;5(5):2000-2004.</ref><ref name="GahukarReddy2019">{{cite journal|last1=Gahukar|first1=Ruparao T|last2=Reddy|first2=Gadi V P|last3=Royer|first3=Tom|title=Management of Economically Important Insect Pests of Millet|journal=Journal of Integrated Pest Management|volume=10|issue=1|year=2019|issn=2155-7470|doi=10.1093/jipm/pmz026|doi-access=free}}</ref> a major pest in India and Africa) |

*shoot fly ''[[Atherigona pulla]]'' (proso millet shoot fly,<ref>Ravulapenta Sathish, M Manjunatha, K Rajashekarappa. [https://www.entomoljournal.com/archives/?year=2017&vol=5&issue=5&ArticleId=2557 Incidence of shoot fly, ''Atherigona pulla'' (Wiedemann) on proso millet at different dates of sowing]. ''[[J Entomol Zool Stud]]'' 2017;5(5):2000-2004.</ref><ref name="GahukarReddy2019">{{cite journal|last1=Gahukar|first1=Ruparao T|last2=Reddy|first2=Gadi V P|last3=Royer|first3=Tom|title=Management of Economically Important Insect Pests of Millet|journal= [[Journal of Integrated Pest Management]] |volume=10|issue=1|year=2019|issn=2155-7470|doi=10.1093/jipm/pmz026|doi-access=free}}</ref> a major pest in India and Africa) |

||

*''[[Atherigona miliaceae]]'', ''[[Atherigona soccata]]'', and ''[[Atherigona punctata]]'' |

*''[[Atherigona miliaceae]]'', ''[[Atherigona soccata]]'', and ''[[Atherigona punctata]]'' |

||

*wheat stem maggot ''[[Meromyza americana]]'' occurs in the United States |

*wheat stem maggot ''[[Meromyza americana]]'' occurs in the United States |

||

Revision as of 20:17, 15 May 2023

| Proso millet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Proso millet panicles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Panicoideae |

| Genus: | Panicum |

| Species: | P. miliaceum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panicum miliaceum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Panicum miliaceum is a grain crop with many common names, including proso millet, broomcorn millet, common millet, hog millet, Kashfi millet, red millet, and white millet.[2] Archaeobotanical evidence suggests millet was first domesticated about 10,000 BP in Northern China.[3] The crop is extensively cultivated in China, India, Nepal, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, the Middle East, Turkey, Romania, and the United States, where about half a million acres are grown each year.[4][better source needed] The crop is notable both for its extremely short lifecycle, with some varieties producing grain only 60 days after planting,[5] and its low water requirements, producing grain more efficiently per unit of moisture than any other grain species tested.[5][6] The name "proso millet" comes from the pan-Slavic general and generic name for millet (Serbo-Croatian: proso/просо, Czech: proso, Polish: proso, Russian: просо). Proso millet is a relative of foxtail millet, pearl millet, maize, and sorghum within the grass subfamily Panicoideae. While all of these crops use C4 photosynthesis, the others all employ the NADP-ME as their primary carbon shuttle pathway, while the primary C4 carbon shuttle in proso millet is the NAD-ME pathway.

Evolutionary history

Panicum miliaceum is a tetraploid species with a base chromosome number of 18, twice the base chromosome number of diploid species within its genus Panicum.[7] The species appears to be an allotetraploid resulting from a wide hybrid between two different diploid ancestors.[8] One of the two subgenomes within proso millet appears to have come from either Panicum capillare/P. capillare or a close relative of that species. The second subgenome does not show close homology to any known diploid Panicum species, but some unknown diploid ancestor apparently also contributed a copy of its genome to a separate allotetraploid species P. repens (torpedo grass).[8] The two subgenomes within proso millet are estimated to have diverged 5.6 million years ago.[9] However, the species has experienced only limited amounts of fractionation and copies of most genes are still retained on both subgenomes.[9] A sequenced version of the proso millet genome, estimated to be around 920 megabase pairs in size, was published in 2019.[9]

Domestication and history of cultivation

Weedy forms of proso millet are found throughout central Asia, covering a widespread area from the Caspian Sea east to Xinjiang and Mongolia. These may represent the wild progenitor of proso millet or feral escapes from domesticated production.[11]: 83 Indeed, in the United States, weedy proso millet, representing feral escapes from cultivation, are now common, suggesting current proso millet cultivars retain the potential to revert, similar to the pattern seen for weedy rice.[12] Currently, the earliest archeological evidence for domesticated proso millet comes from the Cishan site in semiarid north east China around 8,000 BCE.[3] Because early varieties of proso millet had such a short lifecycle, as little as 45 days from planting to harvest, they are thought to have made it possible for seminomadic tribes to first adopt agriculture, forming a bridge between hunter-gatherer-focused lifestyles and early agricultural civilizations.[13] Archaeological evidence for cultivation of domesticated proso millet in east Asia and Europe dates to at least 5,000 BCE in Georgia and Germany (near Leipzig, Hadersleben) by Linear Pottery culture (Early LBK, Neolithikum 5500–4900 BCE),[14] and may represent either an independent domestication of the same wild ancestor, or the spread of the crop from east Asia along trade routes through the arid steppes.[15] Evidence for cultivation in southern Europe and the Near East is comparatively more recent, with the earliest evidence for its cultivation in the Near East a find in the ruins of Nimrud, Iraq, dated to about 700 BC.[11]: 86

Cultivation

Proso millet is a relatively low-demanding crop, and diseases are not known; consequently, it is often used in organic farming systems in Europe. In the United States, it is often used as an intercrop. Thus, proso millet can help to avoid a summer fallow, and continuous crop rotation can be achieved. Its superficial root system and its resistance to atrazine residue make proso millet a good intercrop between two water- and pesticide-demanding crops. The stubbles of the last crop, by allowing more heat into the soil, result in a faster and earlier millet growth. While millet occupies the ground, because of its superficial root system, the soil can replenish its water content for the next crop. Later crops, for example, a winter wheat, can in turn benefit from the millet stubble, which act as snow accumulators.[16] P. miliaceum is commonly classified into five races, miliaceum, patentissimum, contractum, compactum, and ovatum.[17]

Climate and soil requirements

Due to its C4 photosynthetic system, proso millet is thermophilic like maize, so shady locations of the field should be avoided. It is sensitive to temperatures lower than 10 to 13 °C (50 to 55 °F). Proso millet is highly drought-resistant, which makes it of interest to regions with low water availability and longer periods without rain.[18][19] The soil should be light or medium-heavy. Due to its flat root systems, soil compaction must be avoided. Furthermore, proso millet does not tolerate soil wetness caused by dammed-up water.[19]

Seedbed and sowing

The seedbed should be finely crumbled as for sugar beet and rapeseed.[18] In Europe, proso millet is sowed between mid-April and the end of May. About 500 grams per acre (44 oz/ha) of seeds are required, which is roughly 500 per square metre (2,000,000/acre). In organic farming, this amount should be increased if a harrow weeder is used. For sowing, the usual sowing machines can be used similarly to how they are used for other crops such as wheat. A distance between the rows of 16 to 25 centimetres (6.3 to 9.8 in) is recommended if the farmer uses an interrow cultivator. The sowing depth should be 1.5 to 2 centimetres (0.59 to 0.79 in) in optimal soil or 3 to 4 centimetres (1.2 to 1.6 in) in dry soil. Rolling of the ground after sowing is helpful for further cultivation.[18] Cultivation in no-till farming systems is also possible and often practiced in the United States. Sowing then can be done two weeks later.[16]

Field management

Only a few diseases and pests are known to attack proso millet, but they are not economically important. Weeds are a bigger problem. The critical phase is in juvenile development. The formation of the grains happens in the 3- to 5-leaf stage. After that, all nutrients should be available for the millet, so preventing the growth of weeds is necessary. In conventional farming, herbicides may be used. In organic farming, harrow weeder or interrow cultivator use is possible, but special sowing parameters are needed.[18] For good crop development, fertilization with 50 to 75 kilograms (110 to 165 lb) nitrogen per hectare is recommended.[19] Planting proso millet in a crop rotation after maize should be avoided due to its same weed spectrum. Because proso millet is an undemanding crop, it may be used at the end of the rotation.[18]

Harvesting and postharvest treatments

Harvest time is at the end of August until mid-September. Determining the best harvest date is not easy because all the grains do not ripen simultaneously. The grains on the top of the panicle ripen first, while the grains in the lower parts need more time, making compromise and harvest necessary to optimize yield.[18] Harvesting can be done with a conventional combine harvester with the moisture content of the grains around 15-20%. Usually, proso millet is mowed into windrows first, since the plants are not dry like wheat. There, they can wither, which makes the threshing easier. Then the harvest is done with a pickup attached to a combine.[18] Possible yields are between 2.5 and 4.5 tonnes per hectare (1.00 and 1.79 long ton/acre; 1.1 and 2.0 short ton/acre) under optimal conditions. Studies in Germany showed that even higher yields can be attained.[18]

United States

About half of the millet grown in the United States is grown in eastern Colorado on {{ Convert | 340,000 | acre )). Historically grown as animal and bird seed, as of 2020, it has found a market as an organic gluten-free grain.[20]

Uses

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,597 kJ (382 kcal) |

75.1 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 3.5 g |

4.2 g | |

10.8 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 33% 0.4 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 5% 0.07 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 38% 6 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 26% 1.3 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 22% 0.37 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 11% 42 μg |

| Vitamin E | 1% 0.11 mg |

| Vitamin K | 1% 0.8 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 14 mg |

| Iron | 22% 3.9 mg |

| Magnesium | 28% 119 mg |

| Manganese | 43% 1 mg |

| Phosphorus | 23% 285 mg |

| Potassium | 7% 224 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 4 mg |

| Zinc | 24% 2.6 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 8.7 g |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[21] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[22] | |

Proso millet is one of the few types of millet not cultivated in Africa.[23] In the United States, former Soviet Union, and some South American countries, it is primarily grown for livestock feed. As a grain fodder, it is very deficient in lysine and needs complementation. Proso millet is also a poor fodder due to its low leaf-to-stem ratio and a possible irritant effect due to its hairy stem. Foxtail millet, having a higher leaf-to-stem ratio and less hairy stems, is preferred as fodder, particularly the variety called moha, which is a high-quality fodder.

To promote millet cultivation, other potential uses have been considered recently.[24] For example, starch derived from millets has been shown to be a good substrate for fermentation and malting with grains having similar starch contents as wheat grains.[24] A recently published study suggested that starch derived from proso millet can be converted to ethanol with an only moderately lower efficiency than starch derived from corn.[25] The development of varieties with highly fermentable characteristics could improve ethanol yield to that of highly fermentable corn.[25] Since proso millet is compatible with low-input agriculture, cultivation on marginal soils for biofuel production could represent an important new market, such as for farmers in the High Plains of the US.[25] The demand for more diverse and healthier cereal-based foods is increasing, particularly in affluent countries.[26] This could create new markets for proso millet products in human nutrition. Protein content in proso millet grains is comparable with that of wheat, but the share of some essential amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and methionine) is substantially higher in proso millet.[26] In addition, health-promoting phenolic compounds contained in the grains are readily bioaccessible, and their high calcium content favors bone strengthening and dental health.[26] Among the most commonly consumed products are ready-to-eat breakfast cereals made purely from millet flour,[18][26] and a variety of noodles and bakery products that are, however, often produced from mixtures with wheat flour to improve their sensory quality.[26]

Pests

Insect pests include:[27]

- Seedling pests

- shoot fly Atherigona pulla (proso millet shoot fly,[28][29] a major pest in India and Africa)

- Atherigona miliaceae, Atherigona soccata, and Atherigona punctata

- wheat stem maggot Meromyza americana occurs in the United States

- thrip, Haplothrips aculeatus

- armyworms Mythimna separata, Mythimna unipuncta, Spodoptera exempta, and Spodoptera frugiperda

- field cricket Brachytrupes sp.

- Stem borers

- Chilo partellus, Chilo suppressalis, Chilo orichalcociliellus, Sesamia inferens, Sesamia cretica, and Ostrinia furnacalis

- Leaf feeders

- leaf folders Cnaphalocrocis medinalis and Cnaphalocrocis patnalis

- hairy caterpillar Spilosoma obliqua

- rice butterfly Melanitis leda ismene

- Moroccan locust Dociostaurus maroccanus

- migratory locust Locusta migratoria

- grasshoppers Hieroglyphus banian and Oxya chinensis

- Earhead feeders

- cotton boll worm Helicoverpa zea (in the United States)

- Other pests

- aphid Sipha flava (in North America)

- earhead bug Leptocorisa acuta and green bug Nezara viridula suck the milky developing grains in India

- termites, Odontotermes spp. and Microtermes spp., are the common species recorded on proso millet during dry seasons in India.

Names

Names for proso millet in other languages spoken in the countries where it is cultivated include:

- Bengali: cheena

- Odia: china bachari bagmu

- Kannada: baragu

- Telugu: variga

- Hindi: chena or barri

- Punjabi: cheena

- Gujarati: cheno

- Marathi: varaī

- Tamil: pani varagu

- Nepali: dudhe

References

- ^ "Panicum miliaceum L.". The Plant List. 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Panicum miliaceum". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ a b Lu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.-b.; Wu, N.; Li, Y.; Zhou, K.; Ye, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Shen, L.; Xu, D.; Li, Q. (21 April 2009). "Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). 106 (18): 7367–7372. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7367L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900158106. PMC 2678631. PMID 19383791.

- ^ "USDA - National Agricultural Statistics Service Homepage".

- ^ a b Graybosch, R. A.; Baltensperger, D. D. (February 2009). "Evaluation of the waxy endosperm trait in proso millet". Plant Breeding. 128 (1): 70–73. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01511.x.

- ^ Lyman James Briggs; Homer LeRoy Shantz (1913). The water requirement of plants. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 29–.

- ^ Aliscioni, Sandra S.; Giussani, Liliana M.; Zuloaga, Fernando O.; Kellogg, Elizabeth A. (May 2003). "A molecular phylogeny of Panicum (Poaceae: Paniceae): tests of monophyly and phylogenetic placement within the Panicoideae". American Journal of Botany. 90 (5): 796–821. doi:10.3732/ajb.90.5.796. PMID 21659176.

- ^ a b Hunt, H. V.; Badakshi, F.; Romanova, O.; et al. (10 April 2014). "Reticulate evolution in Panicum (Poaceae): the origin of tetraploid broomcorn millet, P. miliaceum". Journal of Experimental Botany (JxB). 65 (12): 3165–3175. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru161. PMC 4071833. PMID 24723408.

- ^ a b c Zou, Changsong; Li, Leiting; Miki, Daisuke; et al. (25 January 2019). "The genome of broomcorn millet". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 436. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..436Z. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08409-5. PMC 6347628. PMID 30683860.

- ^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions" (PDF). Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.4523. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469.

- ^ a b Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria, eds. (2000). Domestication of Plants in the Old World (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press (OUP). ISBN 978-0198503569.

- ^ Thurber, Carrie S.; Reagon, Michael; Gross, Briana L.; et al. (August 2010). "Molecular evolution of shattering loci in U.S. weedy rice". Molecular Ecology. 19 (16): 3271–3284. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04708.x. PMC 2988683. PMID 20584132.

- ^ Fessenden, Maris (January 7, 2016). "This Ancient Grain May Have Helped Humans Become Farmers". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Körber-Grohne, Udelgard (1987). Verlag Theiss (ed.). Nutzpflanzen in Deutschland: Kulturgeschichte und Biologie (in German). ISBN 3-8062-0481-0.

- ^ Hunt, H. V.; Badakshi, F.; Romanova, O.; et al. (10 April 2014). "Reticulate evolution in Panicum (Poaceae): the origin of tetraploid broomcorn millet, P. miliaceum". Journal of Experimental Botany (JxB). 65 (12): 3165–3175. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru161. PMC 4071833. PMID 24723408.

- ^ a b Producing and marketing proso millet in the great plains, U. Nebraska-Lincoln Extension

- ^ Goron, Travis; Raizada, Manish (2015). "Genetic diversity and genomic resources available for the small millet crops to accelerate a New Green Revolution". Frontiers in Plant Science. 6. Frontiers Media SA. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00157. ISSN 1664-462X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Merkblatt für den Anbau von Rispenhirse im biologischen Landbau, www.biofarm.ch, http://www.biofarm.ch/assets/files/Landwirtschaft/Merkblatt_Biohirse_Version%2012_2010.pdf(23.11.14) Archived 2015-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Hanna WW, Baltensperger DD, Seetharam A (2004). "Pearl Millet and Other Millets". In Moser LE, Burson BL, Sollenberger LE (eds.). Warm-Season (C4) Grasses. Agronomy Monographs. pp. 537–560. doi:10.2134/agronmonogr45.c15. ISBN 9780891182375.

- ^ Daliah Singer (July 30, 2020). "Colorado's hottest grain is gluten-free, nutrient-dense, great in beer and about to be your new fav pantry staple Colorado produces the most millet in the country. But what exactly is it?". The Denver Post. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

- ^ National Research Council (1996-02-14). "Ebony". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains. Lost Crops of Africa. Vol. 1. National Academies Press (NAP). p. 260. doi:10.17226/2305. ISBN 978-0-309-04990-0. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ a b Rose DJ, Santra DK (2013). "Proso millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) fermentation for fuel ethanol production". Industrial Crops and Products. 43 (1): 602–605. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.08.010. S2CID 1627015.

- ^ a b c Taylor, J.R.N.; Schober, T.J.; Bean, S.R. (2006). "Novel food and non-food uses for sorghum and millets". Journal of Cereal Science. 44 (3): 252–271. doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2006.06.009.

- ^ a b c d e Saleh AS, Zhang Q, Chen J, Shen Q (2012). "Millet Grains: Nutritional Quality, Processing, and Potential Health Benefits". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 12 (3): 281–295. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12012. S2CID 86749886.

- ^ Kalaisekar, A (2017). Insect pests of millets: systematics, bionomics, and management. London: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-804243-4. OCLC 967265246.

- ^ Ravulapenta Sathish, M Manjunatha, K Rajashekarappa. Incidence of shoot fly, Atherigona pulla (Wiedemann) on proso millet at different dates of sowing. J Entomol Zool Stud 2017;5(5):2000-2004.

- ^ Gahukar, Ruparao T; Reddy, Gadi V P; Royer, Tom (2019). "Management of Economically Important Insect Pests of Millet". Journal of Integrated Pest Management. 10 (1). doi:10.1093/jipm/pmz026. ISSN 2155-7470.

External links

Media related to Panicum miliaceum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Panicum miliaceum at Wikimedia Commons- Alternative Field Crops Manual: Millets