Medieval European magic: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{More footnotes}} {{Expert}} |

add history from Magic (supernatural), see that article's history for contributors; remove most of the witchcraft (=/= magic) material as it is covered elsewhere; I will be expanding with better material though Tags: harv-error Disambiguation links added |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

During the [[Middle Ages]], [[magic (supernatural)|magic]] took on many forms. Instead of being able to identify one type of magic user, there were many who practiced several types of magic in these times, including monks, priests, physicians, surgeons, [[midwife|midwives]], [[folk healer]]s, and [[divination|diviners]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kieckhefer |first=Richard |title=Magic in the Middle Ages |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-107-43182-9 |edition=2nd |location=Cambridge |pages=56}}</ref> The practice of “magic” often consisted of using medicinal herbs for healing purposes. Classical medicine entailed magical elements. They would use charms or potions in hopes of driving out a sickness.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Medievalists.net |date=2021-09-04 |title=Everyday Magic in the Middle Ages |url=https://www.medievalists.net/2021/09/everyday-magic-middle-ages/ |access-date=2022-02-24 |website=Medievalists.net |language=en-US}}</ref> People had strongly differing opinions as to what magic was,<ref name=":12">{{Cite journal |last=Maguire |first=Henry |date=1997 |title=Magic and Money in the Early Middle Ages |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2865957 |journal= Speculum|volume=72 |issue=4 |pages=1037–1054 |doi=10.2307/2865957 |jstor=2865957 |s2cid=162305252 }}</ref> and because of this, it is important to understand all aspects of magic at this time. |

During the [[Middle Ages]], [[magic (supernatural)|magic]] took on many forms. Instead of being able to identify one type of magic user, there were many who practiced several types of magic in these times, including monks, priests, physicians, surgeons, [[midwife|midwives]], [[folk healer]]s, and [[divination|diviners]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kieckhefer |first=Richard |title=Magic in the Middle Ages |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-107-43182-9 |edition=2nd |location=Cambridge |pages=56}}</ref> The practice of “magic” often consisted of using medicinal herbs for healing purposes. Classical medicine entailed magical elements. They would use charms or potions in hopes of driving out a sickness.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Medievalists.net |date=2021-09-04 |title=Everyday Magic in the Middle Ages |url=https://www.medievalists.net/2021/09/everyday-magic-middle-ages/ |access-date=2022-02-24 |website=Medievalists.net |language=en-US}}</ref> People had strongly differing opinions as to what magic was,<ref name=":12">{{Cite journal |last=Maguire |first=Henry |date=1997 |title=Magic and Money in the Early Middle Ages |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2865957 |journal= Speculum|volume=72 |issue=4 |pages=1037–1054 |doi=10.2307/2865957 |jstor=2865957 |s2cid=162305252 }}</ref> and because of this, it is important to understand all aspects of magic at this time. |

||

==History== |

|||

{{Further|Sorcery (goetia)}} |

|||

Magic practices such as divination, interpretation of omens, sorcery, and use of charms had been specifically forbidden in Mosaic Law <ref>{{Bibleverse|Deuteronomy|18:9-18:14|ESV}}</ref> and condemned in Biblical histories of the kings.<ref>{{Bibleverse|2 Chronicles|33:1-33:9|ESV}}</ref> Many of these practices were spoken against in the New Testament as well.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|13:6-13:12|ESV}}</ref><ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|5:16-5:26|ESV}}</ref> |

|||

Some commentators say that in the first century CE, early Christian authors absorbed the [[Greco-Roman world|Greco-Roman]] concept of magic and incorporated it into their developing [[Christian theology]],{{sfn|Otto|Stausberg|2013|p=17}}and that these Christians retained the already implied Greco-Roman negative stereotypes of the term and extented them by incorporating conceptual patterns borrowed from Jewish thought, in particular the opposition of magic and [[miracle]].{{sfn|Otto|Stausberg|2013|p=17}} Some early Christian authors followed the Greek-Roman thinking by ascribing the origin of magic to the human realm, mainly to [[Zoroaster]] and [[Osthanes]]. The Christian view was that magic was a product of the Babylonians, Persians, or Egyptians.{{sfn|Davies|2012|pp=33–34}} The Christians shared with earlier classical culture the idea that magic was something distinct from proper religion, although drew their distinction between the two in different ways.{{sfn|Bailey|2006|p=8}} |

|||

[[File:Isidor von Sevilla.jpeg|thumb|left|A 17th-century depiction of the medieval writer Isidore of Seville, who provided a list of activities he regarded as magical]] |

|||

For early Christian writers like [[Augustine of Hippo]], magic did not merely constitute fraudulent and unsanctioned ritual practices, but was the very opposite of religion because it relied upon cooperation from [[demons]], the henchmen of [[Satan]].{{sfn|Otto|Stausberg|2013|p=17}} In this, Christian ideas of magic were closely linked to the Christian category of [[paganism]],{{sfn|Davies|2012|pp=41–42}} and both magic and paganism were regarded as belonging under the broader category of ''superstitio'' ([[superstition]]), another term borrowed from pre-Christian Roman culture.{{sfn|Bailey|2006|p=8}} This Christian emphasis on the inherent immorality and wrongness of magic as something conflicting with good religion was far starker than the approach in the other large [[Monotheism|monotheistic]] religions of the period, Judaism and Islam.{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=72}} For instance, while Christians regarded demons as inherently evil, the [[jinn]]—comparable entities in [[Islamic mythology]]—were perceived as more ambivalent figures by Muslims.{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=72}} |

|||

The model of the magician in Christian thought was provided by [[Simon Magus]], (Simon the Magician), a figure who opposed [[Saint Peter]] in both the [[Acts of the Apostles]] and the apocryphal yet influential [[Acts of Peter]].{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=99}} The historian Michael D. Bailey stated that in medieval Europe, magic was a "relatively broad and encompassing category".{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=21}} Christian theologians believed that there were multiple different forms of magic, the majority of which were types of [[divination]], for instance, [[Isidore of Seville]] produced a catalogue of things he regarded as magic in which he listed divination by the four elements i.e. [[geomancy]], [[hydromancy]], [[aeromancy]], and [[pyromancy]], as well as by observation of natural phenomena e.g. the flight of birds and astrology. He also mentioned [[incantation|enchantment]] and ligatures (the medical use of magical objects bound to the patient) as being magical.{{sfn|Kieckhefer|2000|pp=10–11}} Medieval Europe also saw magic come to be associated with the Old Testament figure of [[Solomon]]; various [[grimoire]]s, or books outlining magical practices, were written that claimed to have been written by Solomon, most notably the [[Key of Solomon]].{{sfn|Davies|2012|p=35}} |

|||

In early medieval Europe, ''magia'' was a term of condemnation.{{sfn|Flint|1991|p=5}} In medieval Europe, Christians often suspected Muslims and Jews of engaging in magical practices;{{sfnm|1a1=Davies|1y=2012|1p=6|2a1=Bailey|2y=2018|2p=88}} in certain cases, these perceived magical rites—including the [[Blood libel|alleged Jewish sacrifice of Christian children]]—resulted in Christians massacring these religious minorities.{{sfn|Davies|2012|p=6}} Christian groups often also accused other, rival Christian groups such as the [[Hussites]]—which they regarded as [[heresy|heretical]]—of engaging in magical activities.{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=99}}<ref name="Johnson Scribner 1996 p. 47">{{cite book | last1=Johnson | first1=T. | last2=Scribner | first2=R.W. | title=Popular Religion in Germany and Central Europe, 1400-1800 | publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing | series=Themes in Focus | year=1996 | isbn=978-1-349-24836-0 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O5FKEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA47 | access-date=2023-04-02 | page=47}}</ref> Medieval Europe also saw the term ''maleficium'' applied to forms of magic that were conducted with the intention of causing harm.{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=21}} The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: ''sorcière'' in French, ''Hexe'' in German, ''strega'' in Italian, and ''bruja'' in Spanish.{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=22}} The English term for malevolent practitioners of magic, witch, derived from the earlier [[Old English]] term ''wicce''.{{sfn|Bailey|2018|p=22}} |

|||

Ars Magica or magic is a major component and supporting contribution to the belief and practice of spiritual, and in many cases, physical healing throughout the Middle Ages. Emanating from many modern interpretations lies a trail of misconceptions about magic, one of the largest revolving around wickedness or the existence of nefarious beings who practice it. These misinterpretations stem from numerous acts or rituals that have been performed throughout antiquity, and due to their exoticism from the commoner's perspective, the rituals invoked uneasiness and an even stronger sense of dismissal.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Flint|first1=Valerie I.J.|title=The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe|date=1990|publisher=Princeton University Press|location=Princeton, New Jersey|isbn=978-0691031651|pages=4, 12, 406|edition=1st}}</ref><ref name="Kieckhefer 1994">{{cite journal|last1=Kieckhefer|first1=Richard|title=The Specific Rationality of Medieval Magic|journal=The American Historical Review|date=June 1994|volume=99|issue=3|pages=813–818|doi=10.2307/2167771|jstor=2167771|pmid=11639314}}</ref> |

|||

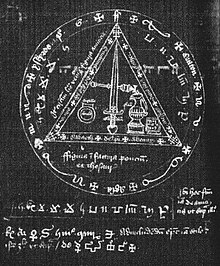

[[File:Sefer raziel segulot.png|thumb|right|An excerpt from [[Sefer Raziel HaMalakh]], featuring various magical [[Sigil (magic)|sigils]] (סגולות ''segulot'' in Hebrew)]] |

|||

In the Medieval Jewish view, the separation of the [[Mysticism|mystical]] and magical elements of Kabbalah, dividing it into speculative [[Kabbalah|theological Kabbalah]] (''Kabbalah Iyyunit'') with its meditative traditions, and theurgic practical Kabbalah (''Kabbalah Ma'asit''), had occurred by the beginning of the 14th century.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Josephy |first1=Marcia Reines |title=Magic & Superstition in the Jewish Tradition: An Exhibition Organized by the Maurice Spertus Museum of Judaica|date=1975 |publisher=Spertus College of Judaica Press|access-date=15 May 2020|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6TPXAAAAMAAJ&q=Magic+%26+Superstition+in+the+Jewish+Tradition|language=en|page=18}}</ref> |

|||

One societal force in the Middle Ages more powerful than the singular commoner, the Christian Church, rejected magic as a whole because it was viewed as a means of tampering with the natural world in a supernatural manner associated with the [[Bible|biblical]] verses of Deuteronomy 18:9–12.{{Explain|reason=There were some major examples of magic practiced in the Middle Ages, although not the stereotypical witchcraft type, that the Church did not take action against.|date=May 2023}} Despite the many negative connotations which surround the term magic, there exist many elements that are seen in a divine or holy light.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Lindberg|first1=David C.|title=The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450|date=2007|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=978-0226482057|page=20|edition=2nd}}</ref> |

|||

The [[divine right of kings]] in [[England]] was thought to be able to give them "[[Sacredness|sacred]] magic" power to heal thousands of their subjects from sicknesses.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Schama |first=Simon |title=A History of Britain 1: 3000 BC-AD 1603 At the Edge of the World? |title-link=A_History_of_Britain_(TV_series)#DVDs_and_books |publisher=[[BBC Worldwide]] |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-563-48714-2 |edition=Paperback 2003 |location=London |pages=193–194 |author-link=Simon Schama}}</ref> |

|||

Diversified instruments or rituals used in medieval magic include, but are not limited to: various amulets, talismans, potions, as well as specific chants, dances, and [[prayer]]s. Along with these rituals are the adversely imbued notions of demonic participation which influence of them. The idea that magic was devised, taught, and worked by demons would have seemed reasonable to anyone who read the Greek magical papyri or the [[Sepher Ha-Razim|Sefer-ha-Razim]] and found that healing magic appeared alongside rituals for killing people, gaining wealth, or personal advantage, and coercing women into sexual submission.{{sfn|Kieckhefer|1994|p=818}} Archaeology is contributing to a fuller understanding of ritual practices performed in the home, on the body and in monastic and church settings.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Gilchrist|first1=Roberta|title=Magic for the Dead? The Archaeology of Magic in Later Medieval Burials|journal=Medieval Archaeology|date=1 November 2008|volume=52|issue=1|pages=119–159|doi=10.1179/174581708x335468|s2cid=162339681|issn=0076-6097|url=http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/3556/1/MED52_05.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150514010744/http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/3556/1/MED52_05.pdf |archive-date=2015-05-14 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Gilchrist|first1=Roberta|title=Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course|date=2012|publisher=Boydell Press|location=Woodbridge|isbn=9781843837220|page=xii|edition=Reprint|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=T3EwHTrRZEsC|access-date=8 March 2017|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Islam and magic|Islamic reaction towards magic]] did not condemn magic in general and distinguished between magic which can heal sickness and [[Demonic possession#Islam|possession]], and sorcery. The former is therefore a special gift from [[God in Islam|God]], while the latter is achieved through help of [[Jinn]] and [[Shaitan|devils]]. [[Ibn al-Nadim]] held that [[exorcist]]s gain their power by their obedience to God, while sorcerers please the devils by acts of disobedience and sacrifices and they in return do him a favor.<ref>{{cite book|last1=El-Zein|first1=Amira|title=Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn|date=2009|publisher=Syracuse University Press|location=Syracuse, New York|isbn=9780815650706|page=77}}</ref> According to [[Ibn Arabi]], Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yusuf al-Shubarbuli was able to walk on water due to his piety.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Lebling|first1=Robert|title=Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar|date=2010|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=9780857730633|page=51}}</ref> According to the Quran 2:102, magic was also taught to humans by devils and the [[Fallen angel#Islam|fallen angels]] [[Harut and Marut]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Nasr|first1=Seyyed Hossein|last2=Dagli|first2=Caner K.|last3=Dakake|first3=Maria Massi|last4=Lumbard|first4=Joseph E.B.|last5=Rustom|first5=Mohammed|title=The Study Quran; A New Translation and Commentary|date=2015|publisher=Harper Collins|isbn=9780062227621|page=25}}</ref> |

|||

== Medieval magic == |

== Medieval magic == |

||

| Line 38: | Line 64: | ||

=== Prosecution in the Early Middle Ages === |

=== Prosecution in the Early Middle Ages === |

||

Important political figures were the most frequently known characters in trials against magic, whether defendants, accusers, or victims. This was because high-society trials were more likely to be recorded as opposed to trials involving ordinary townspeople or villagers. For example, [[Gregory of Tours]] recorded the accusations of magic at the royal court of 6th century [[Gaul]]. According to [[Historia Francorum|History of the Franks]], two people were executed for supposedly bewitching [[emperor Arnulf]] and prompting the stroke that led to his death. Prosecution of magic was infrequent during this era because Christians were willing to adapt magic practices within the context of religion. For example, astrology was created by the Greeks, who were considered to be [[pagans]] by Medieval Christians. Astrology was condemned if it were used to control destiny because the Christian God is supposed to be the one who controls destiny. Early Christians were accommodating of astrology as long as it was connected to the physical realm as opposed to the spiritual.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Aveni |first=Anthony F. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50091675 |title=Behind the crystal ball : magic, science, and the occult from antiquity through the New Age |publisher=University Press of Colorado |year=2002 |isbn=0-87081-671-3 |edition=Rev. |location=Boulder, Colo. |pages=101–102 |oclc=50091675}}</ref> |

|||

=== Rise of witch trials === |

=== Rise of witch trials === |

||

{{futher|Witch-hunt|Witch trials in the early modern period}} |

|||

The rise of witch trials is brought about by changes in religion as well as changes to the political world in Europe showing once again how different topics had an influence on witchcraft.The fourteenth century already brought about an increase of [[Maleficium (sorcery)|sorcery]] trials, however the second and third quarters of the fifteenth century were known for the most dramatic uprising of trials involving witchcraft.<ref name=":52">{{Cite book |last=Bennett |first=Judith M. |title=The Oxford Handbook of Women & Gender In Medieval Europe |publisher=University Press |year=2013 |pages=578–587}}</ref> The trials developed into catch-all prosecution, in which townspeople were encouraged to seek out as many suspects as possible. The goal was no longer to secure [[justice]] against a single offender but rather to purge the community of all transgressors |

The rise of witch trials is brought about by changes in religion as well as changes to the political world in Europe showing once again how different topics had an influence on witchcraft.The fourteenth century already brought about an increase of [[Maleficium (sorcery)|sorcery]] trials, however the second and third quarters of the fifteenth century were known for the most dramatic uprising of trials involving witchcraft.<ref name=":52">{{Cite book |last=Bennett |first=Judith M. |title=The Oxford Handbook of Women & Gender In Medieval Europe |publisher=University Press |year=2013 |pages=578–587}}</ref> The trials developed into catch-all prosecution, in which townspeople were encouraged to seek out as many suspects as possible. The goal was no longer to secure [[justice]] against a single offender but rather to purge the community of all transgressors. |

||

The stereotype of the witch finally solidified in the late [[Middle Ages]]. Numerous texts singled out women to be especially inclined to witchcraft. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, women defendants outnumbered men two to one. This difference only became more pronounced in the following centuries. The disparity between women and men defendants was primarily due to the position women held in late medieval society. Women in this era were far less trusted than men, as they were thought to be weak minded and easily dissuaded. General [[misogynist]] stereotypes further encouraged their [[prosecution]], which lead to a more stiffened [[stereotype]] of witches. Massive witch trials swept across Europe in the second half of the fifteenth century. In 1428, more than 100 people were burned for killing others, destroying crops, and working harm by means of magic. This trial in the [[Valais]] provided the first evidence for the fully developed stereotype of a witch, including flight through the air, transforming humans into animals, eating babies and the veneration of the [[Devil]]. The unrestricted use of torture in combination with the adoption of inquisitorial procedures as well as the development of the witch stereotype and a dramatic rise in public suspicion ultimately caused the swelling fervor and frequency of these sweeping witch hunts. |

|||

== Magic and Christianity == |

== Magic and Christianity == |

||

Witchcraft and magic has connections to many other topics in the Middle Ages, making it a very important and influential topic. It has a large connection to religion due to the fact that Christianity had a major impact on those who practiced magic. When Christianity became more strict it viewed witches as atheists, in turn prosecuting them for it.<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Ben-Yehuda |first=Nachman |date=1980 |title=The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist Perspective |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2778849 |journal=American Journal of Sociology |volume=86 |issue=1 |pages=2–32 |doi=10.1086/227200 |jstor=2778849 |s2cid=143650714 |via=JSTOR}}</ref> Christianity and Catholicism grew with movements like the Spanish Reconquista, which ended in 1492 when Spain conquered Granada. This movement was a crusade and those involved forced others to convert to Christianity.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kroesen |first=Justin E.A. |date=2008 |title=From Mosques to Cathedrals: Converting Sacred Space During the Spanish Reconquest |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/42586616 |journal=Mediaevistik |volume=21 |pages=113–137 |doi=10.3726/83010_113 |jstor=42586616 |via=JSTOR}}</ref> |

Witchcraft and magic has connections to many other topics in the Middle Ages, making it a very important and influential topic. It has a large connection to religion due to the fact that Christianity had a major impact on those who practiced magic. When Christianity became more strict it viewed witches as atheists, in turn prosecuting them for it.<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Ben-Yehuda |first=Nachman |date=1980 |title=The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist Perspective |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2778849 |journal=American Journal of Sociology |volume=86 |issue=1 |pages=2–32 |doi=10.1086/227200 |jstor=2778849 |s2cid=143650714 |via=JSTOR}}</ref> Christianity and Catholicism grew with movements like the Spanish Reconquista, which ended in 1492 when Spain conquered Granada. This movement was a crusade and those involved forced others to convert to Christianity.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kroesen |first=Justin E.A. |date=2008 |title=From Mosques to Cathedrals: Converting Sacred Space During the Spanish Reconquest |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/42586616 |journal=Mediaevistik |volume=21 |pages=113–137 |doi=10.3726/83010_113 |jstor=42586616 |via=JSTOR}}</ref> |

||

== Women in magic == |

|||

During the Middle Ages around 60,000 people died during the early modern witch hunts, and as many as 70 percent of these people were women.<ref name=":52"/> Men began to see illiterate women as beings who held the power of sorcery, and witchcraft began to be viewed as satanic. The reason witches were mainly seen as women can be traced back to the Germanic legend of the Alpine witch, which stated that the details of demonology were strictly female.<ref name=":52" /> Women in medicine held titles such as healers and midwives, which had connections to witchcraft.<ref name=":42"/> With changes in the church came changes in the role of women, which influenced these prosecutions.<ref name=":6" /> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 21:50, 27 September 2023

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2023) |

This article needs attention from an expert in history. The specific problem is: history is all muddled together and exceeds scope of article by including Early Modern era material. (September 2023) |

During the Middle Ages, magic took on many forms. Instead of being able to identify one type of magic user, there were many who practiced several types of magic in these times, including monks, priests, physicians, surgeons, midwives, folk healers, and diviners.[1] The practice of “magic” often consisted of using medicinal herbs for healing purposes. Classical medicine entailed magical elements. They would use charms or potions in hopes of driving out a sickness.[2] People had strongly differing opinions as to what magic was,[3] and because of this, it is important to understand all aspects of magic at this time.

History

Magic practices such as divination, interpretation of omens, sorcery, and use of charms had been specifically forbidden in Mosaic Law [4] and condemned in Biblical histories of the kings.[5] Many of these practices were spoken against in the New Testament as well.[6][7]

Some commentators say that in the first century CE, early Christian authors absorbed the Greco-Roman concept of magic and incorporated it into their developing Christian theology,[8]and that these Christians retained the already implied Greco-Roman negative stereotypes of the term and extented them by incorporating conceptual patterns borrowed from Jewish thought, in particular the opposition of magic and miracle.[8] Some early Christian authors followed the Greek-Roman thinking by ascribing the origin of magic to the human realm, mainly to Zoroaster and Osthanes. The Christian view was that magic was a product of the Babylonians, Persians, or Egyptians.[9] The Christians shared with earlier classical culture the idea that magic was something distinct from proper religion, although drew their distinction between the two in different ways.[10]

For early Christian writers like Augustine of Hippo, magic did not merely constitute fraudulent and unsanctioned ritual practices, but was the very opposite of religion because it relied upon cooperation from demons, the henchmen of Satan.[8] In this, Christian ideas of magic were closely linked to the Christian category of paganism,[11] and both magic and paganism were regarded as belonging under the broader category of superstitio (superstition), another term borrowed from pre-Christian Roman culture.[10] This Christian emphasis on the inherent immorality and wrongness of magic as something conflicting with good religion was far starker than the approach in the other large monotheistic religions of the period, Judaism and Islam.[12] For instance, while Christians regarded demons as inherently evil, the jinn—comparable entities in Islamic mythology—were perceived as more ambivalent figures by Muslims.[12]

The model of the magician in Christian thought was provided by Simon Magus, (Simon the Magician), a figure who opposed Saint Peter in both the Acts of the Apostles and the apocryphal yet influential Acts of Peter.[13] The historian Michael D. Bailey stated that in medieval Europe, magic was a "relatively broad and encompassing category".[14] Christian theologians believed that there were multiple different forms of magic, the majority of which were types of divination, for instance, Isidore of Seville produced a catalogue of things he regarded as magic in which he listed divination by the four elements i.e. geomancy, hydromancy, aeromancy, and pyromancy, as well as by observation of natural phenomena e.g. the flight of birds and astrology. He also mentioned enchantment and ligatures (the medical use of magical objects bound to the patient) as being magical.[15] Medieval Europe also saw magic come to be associated with the Old Testament figure of Solomon; various grimoires, or books outlining magical practices, were written that claimed to have been written by Solomon, most notably the Key of Solomon.[16]

In early medieval Europe, magia was a term of condemnation.[17] In medieval Europe, Christians often suspected Muslims and Jews of engaging in magical practices;[18] in certain cases, these perceived magical rites—including the alleged Jewish sacrifice of Christian children—resulted in Christians massacring these religious minorities.[19] Christian groups often also accused other, rival Christian groups such as the Hussites—which they regarded as heretical—of engaging in magical activities.[13][20] Medieval Europe also saw the term maleficium applied to forms of magic that were conducted with the intention of causing harm.[14] The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: sorcière in French, Hexe in German, strega in Italian, and bruja in Spanish.[21] The English term for malevolent practitioners of magic, witch, derived from the earlier Old English term wicce.[21]

Ars Magica or magic is a major component and supporting contribution to the belief and practice of spiritual, and in many cases, physical healing throughout the Middle Ages. Emanating from many modern interpretations lies a trail of misconceptions about magic, one of the largest revolving around wickedness or the existence of nefarious beings who practice it. These misinterpretations stem from numerous acts or rituals that have been performed throughout antiquity, and due to their exoticism from the commoner's perspective, the rituals invoked uneasiness and an even stronger sense of dismissal.[22][23]

In the Medieval Jewish view, the separation of the mystical and magical elements of Kabbalah, dividing it into speculative theological Kabbalah (Kabbalah Iyyunit) with its meditative traditions, and theurgic practical Kabbalah (Kabbalah Ma'asit), had occurred by the beginning of the 14th century.[24]

One societal force in the Middle Ages more powerful than the singular commoner, the Christian Church, rejected magic as a whole because it was viewed as a means of tampering with the natural world in a supernatural manner associated with the biblical verses of Deuteronomy 18:9–12.[further explanation needed] Despite the many negative connotations which surround the term magic, there exist many elements that are seen in a divine or holy light.[25]

The divine right of kings in England was thought to be able to give them "sacred magic" power to heal thousands of their subjects from sicknesses.[26]

Diversified instruments or rituals used in medieval magic include, but are not limited to: various amulets, talismans, potions, as well as specific chants, dances, and prayers. Along with these rituals are the adversely imbued notions of demonic participation which influence of them. The idea that magic was devised, taught, and worked by demons would have seemed reasonable to anyone who read the Greek magical papyri or the Sefer-ha-Razim and found that healing magic appeared alongside rituals for killing people, gaining wealth, or personal advantage, and coercing women into sexual submission.[27] Archaeology is contributing to a fuller understanding of ritual practices performed in the home, on the body and in monastic and church settings.[28][29]

The Islamic reaction towards magic did not condemn magic in general and distinguished between magic which can heal sickness and possession, and sorcery. The former is therefore a special gift from God, while the latter is achieved through help of Jinn and devils. Ibn al-Nadim held that exorcists gain their power by their obedience to God, while sorcerers please the devils by acts of disobedience and sacrifices and they in return do him a favor.[30] According to Ibn Arabi, Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yusuf al-Shubarbuli was able to walk on water due to his piety.[31] According to the Quran 2:102, magic was also taught to humans by devils and the fallen angels Harut and Marut.[32]

Medieval magic

Medical magic

Medical care in the Middle Ages was extremely broad and took many different forms. Practices like therapy revolved around plants, animals, and minerals at this time.[3] Medicinal practices in the Middle Ages were often regarded as herbalism.[3] One example of a book that gave recipes and descriptions of plants, animals, and minerals was referred to as a “leechbook”, or a doctor-book that included Masses to be said to bless the healing herbs. There were over 400 herbs and plants recorded in different medical books produced during this time.[33] For example, a procedure for curing skin disease first involves an ordinary herbal medicine followed by strict instructions to draw blood from the neck of the ill, pour it into running water, spit three times and recite a sort of spell to complete the cure. In addition to the leechbook, the Lacnunga included many prescriptions derived from the European folk culture. The Lacnunga prescribed a set of Christian prayers to be said over the ingredients used to make the medicine, and such ingredients were to be mixed by straws with the names “Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John” inscribed on them. In order for the cure to work, several charms had to be sung in Latin over the medicine. Books like the "leechbook" and the Lacnunga were essentially recipe books that contained details on what each recipe could be used for and it gave detailed descriptions of the plants that were used for healing. Each book contained different content, because popular belief was always changing.

Astrology

Astrology in its rudimentary form was categorized under spirituality. However, many of the subsections under medieval magic relied on the contextual information within astrology in order to be effective. People who practiced magic often relied on the influence of astrological power for their practices.[34] The presence of astrology in the Middle Ages is recorded on the walls of the San Miniato al Monte basilica in Florence, Italy. The art on the walls of the basilica depict all of the zodiac symbols. Each of the zodiac during this era were connected with a specific part of the human body that it was deeply connected to.[35] People who practice magic during this period could take the zodiac into consideration of the practices more precisely if it were directly related to body parts.

Divination

Divination in the Middle Ages can be used as a broad term to define practices used to understand or foresee one's fate and to connect with the entities that brought about said fate. There were multiple ways by which people could attempt divination. Tarot cards were present during the Middle Ages, but it is not clear how the cards were used and interpreted during this period. However, the general placement of the cards would have affected the interpretation of the message.[36]

Charms

Prayers, blessings, and adjurations were all common forms of verbal formulas whose intentions were hard to distinguish between the magical and the religious. In the Christian context, prayers were typically requests directed to a holy figure such as God, a saint, Christ, or Mary. Blessings more often were addressed to patients, and came in the form of wishes for good fortune. Adjurations, which is defined as the process of making an oath, are also used as exorcisms were more directed to either a sickness, or the agent responsible such as a worm, ghost, demon, or fairy of a mischievous or malevolent nature. While these three verbal formulas may have had religious intentions, they often played a role in magical practices. Blessings were more often than not strictly religious as well, unless they were used alongside magic or in a magical context. However, adjurations required closer scrutiny, as their formulas were generally derived from folklore. Though people at this age were less concerned with whether or not these verbal formulas involved magic or not, but rather with the reality of if they were or were not successful, because they were used to heal.

In addition to the Christian base of charms, tangible items were incorporated into the magical practice. Such items included amulets, talismans, gemstones, as well as smaller items that were used to create the amulets. These items were convenient because they could be kept on one's person at all times, and they served many purposes. They could protect the user from multiple forms of danger, bring the user good fortune, or they could combine multiple blessings and protections depending on how the charm user interacted with them.[37]

Sorcery

Not only was it difficult to make the distinction between the magical and religious, but what was even more challenging was to distinguish between helpful (white) magic from harmful (black) magic. Medical magic and protective magic were regarded as helpful, and called ‘white’, while sorcery was considered evil and ‘black’. Distinguishing between black magic and white magic often relied on perspective, for example, if a healer attempted to cure a patient and failed, some would accuse the healer of intentionally harming the patient. In this era, magic was only punished if it was deemed to be ‘black’, meaning it was the practice of a sorcerer with harmful intention.

Opposition

Early opposition

Views on magic changed throughout the years and as time went on more controls were placed on magic, these controls varied from place to place and also depended on social status.[38] One of the main reasons magic was condemned was because those who practiced it put themselves at risk of physical and spiritual assault from the demons they sought to control. However, the overarching concern of magical practices was the grievous harm it could do to others. Magic represented a huge threat to an age that widely professed belief in religion and holy powers.

Legal prohibitions

Legislation against magic could be one of two types, either by secular authorities or by the Church.[38] The penalties assigned by secular law typically included execution, but were more severe based on the impact of the magic, as people were less concerned with the means of magic, and more concerned with its effects on others. The penalties by the Church often required penance for, what they viewed as the sin of magic, or in harsher cases could excommunicate the accused under the circumstances that the work of magic was a direct offense against God. The distinction between these punishments, secular versus the Church, were not absolute as many of the laws enacted by both parties were derived from the other.

The persecution of magic can be seen in law codes dating back to the 6th century, where the Germanic code of Visigoths condemned sorcerers who cursed the crops and animals of peasant's enemies. In terms of secular legislation, Charles the Great (Charlemagne) was arguably the strongest opposing force to magic. He declared that all who practiced sorcery or divination would become slaves to the Church, and all those who sacrificed to the Devil or Germanic gods would be executed.

Charlemagne's objection to magic carried over into later years, as many rulers built on his early prohibitions. King Roger II of Sicily punished the use of poisons by death, whether natural or magical. Additionally, he proclaimed that ‘love magic’ be punished regardless of if anyone was hurt or not. However, secular rulers were still more concerned with the actual damage of the magic rather than the means of its infliction.

Instructions issued in 800 at a synod in Freising provide general outlines for ecclesiastical hearings. The document states that those accused of some type of sorcery were to be examined by the archpriest of the diocese in hopes of prompting a confession. Torture was used if necessary, and the accused were often sentenced to prison until they resolved to do penance for their sins.

Prosecution in the Early Middle Ages

Important political figures were the most frequently known characters in trials against magic, whether defendants, accusers, or victims. This was because high-society trials were more likely to be recorded as opposed to trials involving ordinary townspeople or villagers. For example, Gregory of Tours recorded the accusations of magic at the royal court of 6th century Gaul. According to History of the Franks, two people were executed for supposedly bewitching emperor Arnulf and prompting the stroke that led to his death. Prosecution of magic was infrequent during this era because Christians were willing to adapt magic practices within the context of religion. For example, astrology was created by the Greeks, who were considered to be pagans by Medieval Christians. Astrology was condemned if it were used to control destiny because the Christian God is supposed to be the one who controls destiny. Early Christians were accommodating of astrology as long as it was connected to the physical realm as opposed to the spiritual.[39]

Rise of witch trials

Template:Futher The rise of witch trials is brought about by changes in religion as well as changes to the political world in Europe showing once again how different topics had an influence on witchcraft.The fourteenth century already brought about an increase of sorcery trials, however the second and third quarters of the fifteenth century were known for the most dramatic uprising of trials involving witchcraft.[40] The trials developed into catch-all prosecution, in which townspeople were encouraged to seek out as many suspects as possible. The goal was no longer to secure justice against a single offender but rather to purge the community of all transgressors.

Magic and Christianity

Witchcraft and magic has connections to many other topics in the Middle Ages, making it a very important and influential topic. It has a large connection to religion due to the fact that Christianity had a major impact on those who practiced magic. When Christianity became more strict it viewed witches as atheists, in turn prosecuting them for it.[41] Christianity and Catholicism grew with movements like the Spanish Reconquista, which ended in 1492 when Spain conquered Granada. This movement was a crusade and those involved forced others to convert to Christianity.[42]

See also

References

- ^ Kieckhefer, Richard (2014). Magic in the Middle Ages (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-107-43182-9.

- ^ Medievalists.net (2021-09-04). "Everyday Magic in the Middle Ages". Medievalists.net. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ a b c Maguire, Henry (1997). "Magic and Money in the Early Middle Ages". Speculum. 72 (4): 1037–1054. doi:10.2307/2865957. JSTOR 2865957. S2CID 162305252.

- ^ Deuteronomy 18:9–18:14

- ^ 2 Chronicles 33:1–33:9

- ^ Acts 13:6–13:12

- ^ Galatians 5:16–5:26

- ^ a b c Otto & Stausberg 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Davies 2012, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b Bailey 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Davies 2012, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Bailey 2018, p. 72.

- ^ a b Bailey 2018, p. 99.

- ^ a b Bailey 2018, p. 21.

- ^ Kieckhefer 2000, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Davies 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Flint 1991, p. 5.

- ^ Davies 2012, p. 6; Bailey 2018, p. 88.

- ^ Davies 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Johnson, T.; Scribner, R.W. (1996). Popular Religion in Germany and Central Europe, 1400-1800. Themes in Focus. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-349-24836-0. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ a b Bailey 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Flint, Valerie I.J. (1990). The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (1st ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 4, 12, 406. ISBN 978-0691031651.

- ^ Kieckhefer, Richard (June 1994). "The Specific Rationality of Medieval Magic". The American Historical Review. 99 (3): 813–818. doi:10.2307/2167771. JSTOR 2167771. PMID 11639314.

- ^ Josephy, Marcia Reines (1975). Magic & Superstition in the Jewish Tradition: An Exhibition Organized by the Maurice Spertus Museum of Judaica. Spertus College of Judaica Press. p. 18. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450 (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0226482057.

- ^ Schama, Simon (2003). A History of Britain 1: 3000 BC-AD 1603 At the Edge of the World? (Paperback 2003 ed.). London: BBC Worldwide. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-563-48714-2.

- ^ Kieckhefer 1994, p. 818.

- ^ Gilchrist, Roberta (1 November 2008). "Magic for the Dead? The Archaeology of Magic in Later Medieval Burials" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 52 (1): 119–159. doi:10.1179/174581708x335468. ISSN 0076-6097. S2CID 162339681. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-14.

- ^ Gilchrist, Roberta (2012). Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course (Reprint ed.). Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. xii. ISBN 9781843837220. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ El-Zein, Amira (2009). Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780815650706.

- ^ Lebling, Robert (2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B.Tauris. p. 51. ISBN 9780857730633.

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Dagli, Caner K.; Dakake, Maria Massi; Lumbard, Joseph E.B.; Rustom, Mohammed (2015). The Study Quran; A New Translation and Commentary. Harper Collins. p. 25. ISBN 9780062227621.

- ^ Stannard, Jerry (2013). "Medieval Herbalism and Post-Medieval Folk Medicine". Pharmacy in History. 55 (2–3): 47–54. PMID 25654900 – via JTSTOR.

- ^ Aveni, Anthony F. (2002). Behind the crystal ball : magic, science, and the occult from antiquity through the New Age. Boulder, Colo.: University Press of Colorado. p. 101. ISBN 0-87081-671-3. OCLC 50091675.

- ^ Gettings, Fred (1987). The secret zodiac : the hidden art in mediaeval astrology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-7102-1147-3. OCLC 15520872.

- ^ Aveni, Anthony (1996). Behind the Crystal Ball. University Press of Colorado. pp. 77–78. ISBN 9780870816710.

- ^ Jolly, Karen Louise (2002). The Middle Ages. Catharina Raudvere, Edward Peters, Bengt Ankarloo, Stuart Clark. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-8122-3616-5. OCLC 49564409.

- ^ a b Waite, Gary K. (2012). "Laura Stokes. Demons of Urban Reform: Early European Witch Trials and Criminal Justice, 1430–1530. Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. vii + 236 pp. $85. ISBN: 978–1–4039–8683–2". Renaissance Quarterly. 65 (1): 261–263. doi:10.1086/665886. ISSN 0034-4338. S2CID 164023962.

- ^ Aveni, Anthony F. (2002). Behind the crystal ball : magic, science, and the occult from antiquity through the New Age (Rev. ed.). Boulder, Colo.: University Press of Colorado. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-87081-671-3. OCLC 50091675.

- ^ Bennett, Judith M. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Women & Gender In Medieval Europe. University Press. pp. 578–587.

- ^ Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (1980). "The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist Perspective". American Journal of Sociology. 86 (1): 2–32. doi:10.1086/227200. JSTOR 2778849. S2CID 143650714 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Kroesen, Justin E.A. (2008). "From Mosques to Cathedrals: Converting Sacred Space During the Spanish Reconquest". Mediaevistik. 21: 113–137. doi:10.3726/83010_113. JSTOR 42586616 – via JSTOR.