Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Expanding article |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

||

| name = Drug-induced autoimmune heamolytic anemia |

| name = Drug-induced autoimmune heamolytic anemia |

||

| synonyms = |

| synonyms = Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia, DIIHA. |

||

| image = |

| image = Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia blood smear.jpg |

||

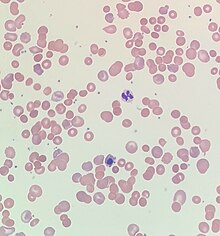

| caption = [[Blood smear]] from a patient with [[warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia]] showing [[spherocytes]], marked [[polychromasia]] and a [[nucleated red blood cell]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| pronounce = |

| pronounce = |

||

| field = [[Hematology]] |

| field = [[Hematology]] |

||

| symptoms = [[Fatigue]], [[shortness of breath]], [[dizziness]], [[bloody urine]], [[jaundice]], [[weakness]], and [[palpitations]]<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| complications = [[Hemolysis]], [[Shock (circulatory)|shock]], [[ischemia]], [[acute respiratory distress syndrome]], [[disseminated intravascular coagulation]],<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> and acute [[renal failure]].<ref name="Chen Zhan p. "/> |

|||

| complications = |

|||

| onset = Hours to months of the initial drug exposure.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| duration = |

| duration = |

||

| types = |

| types = |

||

| causes = [[Antimicrobial]]s, [[nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug]]s, [[antineoplastic]] drugs, and other drugs.<ref name="Garratty 2009 pp. 73–79"/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| risks = |

| risks = |

||

| diagnosis = Blood tests, [[blood smear]], and [[Direct antiglobulin test]]ing<ref name="Hill Stamps Massey Grainger 2017 pp. 208–220"./> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| differential = [[Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia]].<ref name="Hill Stamps Massey Grainger 2017 pp. 208–220"/> |

|||

| differential = |

|||

| prevention = |

| prevention = |

||

| treatment = Stopping the offending drug, [[Blood transfusion|blood transfusions]], and [[thromboprophylaxis]].<ref name="Hill Stamps Massey Grainger 2017 pp. 208–220"/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| medication = |

| medication = |

||

| prognosis = |

| prognosis = |

||

| frequency = One to two people per million worldwide.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| deaths = |

| deaths = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia''' also known as '''Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia''' (DIIHA) is a rare cause of [[hemolytic anemia]]. It is difficult to differentiate from other forms of [[anemia]] which can lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Many different types of [[Antibiotic|antibiotics]] can cause DIIHA and discontinuing the offending medication is the first line of treatment. DIIHA has is estimated to affect one to two people per million worldwide.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. ">{{cite journal | last=Chan Gomez | first=Janet | last2=Saleem | first2=Tabinda | last3=Snyder | first3=Samantha | last4=Joseph | first4=Maria | last5=Kanderi | first5=Tejaswi | title=Drug-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia due to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate: A Case Report and Review | journal=Cureus | publisher=Cureus, Inc. | date=June 17, 2020 | issn=2168-8184 | doi=10.7759/cureus.8666 |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7370667/|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

'''Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia''' is a form of [[hemolytic anemia]]. |

|||

In some cases, a drug can cause the immune system to mistakenly think the body's own [[red blood cells]] are dangerous, foreign substances. [[Antibodies]] then develop against the red blood cells. The antibodies attach to red blood cells and cause them to break down too early. It is known that more than 150 drugs can cause this type of [[hemolytic anemia]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Barcellini|first=Wilma|date=2015-10-01|title=Immune Hemolysis: Diagnosis and Treatment Recommendations|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0037196315000463|journal=Seminars in Hematology|series=Anemia in Clinical Practice|volume=52|issue=4|pages=304–312|doi=10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.05.001|pmid=26404442|issn=0037-1963}}</ref> The list includes |

In some cases, a drug can cause the immune system to mistakenly think the body's own [[red blood cells]] are dangerous, foreign substances. [[Antibodies]] then develop against the red blood cells. The antibodies attach to red blood cells and cause them to break down too early. It is known that more than 150 drugs can cause this type of [[hemolytic anemia]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Barcellini|first=Wilma|date=2015-10-01|title=Immune Hemolysis: Diagnosis and Treatment Recommendations|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0037196315000463|journal=Seminars in Hematology|series=Anemia in Clinical Practice|volume=52|issue=4|pages=304–312|doi=10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.05.001|pmid=26404442|issn=0037-1963}}</ref> The list includes: |

||

* [[Cephalosporins]] (a class of antibiotics) |

* [[Cephalosporins]] (a class of antibiotics) |

||

* [[Dapsone]] |

* [[Dapsone]] |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

* [[Quinidine]]<ref>{{MedlinePlusEncyclopedia|000578|Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia}}</ref> |

* [[Quinidine]]<ref>{{MedlinePlusEncyclopedia|000578|Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia}}</ref> |

||

==Signs and symptoms== |

|||

[[Penicillin]] in high doses can induce immune mediated hemolysis<ref name="pmid10815791">{{cite journal |last1=Stroncek |first1=David |last2=Procter |first2=Jo L. |last3=Johnson |first3=Judy |title=Drug-induced hemolysis: Cefotetan-dependent hemolytic anemia mimicking an acute intravascular immune transfusion reaction |journal=American Journal of Hematology |volume=64 |issue=1 |pages=67–70 |year=2000 |pmid=10815791 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(200005)64:1<67::AID-AJH12>3.0.CO;2-Z |doi-access=free }}</ref> via the [[hapten]] mechanism in which antibodies are targeted against the combination of penicillin in association with red blood cells. Complement is activated by the attached antibody leading to the removal of red blood cells by the spleen.{{citation needed|date=August 2015}} |

|||

Initial symptoms of drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia are typically vague and reflect mild, moderate, or severe [[anemia]]. Symptoms of DIIHA can manifest within hours to months of the initial drug exposure.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> DIIHA ranges in severity from severe [[intravascular hemolysis]] to milder presentations of [[extravascular hemolysis]].<ref name="Karunathilaka Chandrasiri Ranasinghe Ratnamalala 2020 pp. 1–3">{{cite journal | last=Karunathilaka | first=H. G. C. S. | last2=Chandrasiri | first2=D. P. | last3=Ranasinghe | first3=P. | last4=Ratnamalala | first4=V. | last5=Fernando | first5=A. H. N. | title=Co-Amoxiclav Induced Immune Haemolytic Anaemia: A Case Report | journal=Case Reports in Hematology | publisher=Hindawi Limited | volume=2020 | date=March 31, 2020 | issn=2090-6560 | doi=10.1155/2020/9841097 | pages=1–3|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150724/|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> Common symptoms of DIIHA are [[fatigue]], [[shortness of breath]], [[dizziness]], [[Bloody urine|bloody]] or dark urine,<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> [[weakness]], and [[palpitations]]. DIIHA will occasionally present as [[hemoglobinuria]] with [[chills]], however this is quite rare.<ref name="Chen Zhan p. ">{{cite journal | last=Chen | first=Fei | last2=Zhan | first2=Zhuying | title=Severe drug-induced immune haemolytic anaemia due to ceftazidime | journal=Blood Transfusion | publisher=Edizioni SIMTI | pmid=24887228| doi=10.2450/2014.0237-13 |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4111830/|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> Patients with DIIHA may appear pale and have [[jaundice]]. [[Hepatomegaly]], [[splenomegaly]], and [[adenopathy]] have also been observed.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> |

|||

When DIIHA is not recognized promptly it can have life-threatening complications such as [[hemolysis]] leading to [[Shock (circulatory)|shock]], [[ischemia]], [[acute respiratory distress syndrome]], [[disseminated intravascular coagulation]],<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> and acute [[renal failure]].<ref name="Chen Zhan p. "/> |

|||

The drug itself can be targeted by the immune system, e.g. by [[IgE]] in a [[Type I hypersensitivity reaction]] to penicillin, rarely leading to anaphylaxis.{{citation needed|date=August 2015}} |

|||

==Causes== |

|||

As of 2020 over 130 drugs have been reported to cause DIIHA. That number will continue to rise as new drugs are discovered.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> [[Antimicrobial]]s are responsible for 42% of DIIHA cases, making them the most common cause. [[Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug|Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs]] cause about 15% of cases and [[antineoplastic]] drugs cause around 11%.<ref name="Garratty 2009 pp. 73–79">{{cite journal | last=Garratty | first=George | title=Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia | journal=Hematology | publisher=American Society of Hematology | volume=2009 | issue=1 | date=January 1, 2009 | issn=1520-4391 | doi=10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.73 | pages=73–79|url=https://ashpublications.org/hematology/article/2009/1/73/19772/Drug-induced-immune-hemolytic-anemia|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

==Mechanism== |

|||

The main mechanism of DIIHA is the development of [[antibodies]]. Drug-induced antibodies can be classified into two groups, drug-dependent antibodies and drug-independent autoantibodies. Drug-dependent antibodies are common in DIIHA. They require the offending drug to be present in order to bind and lyse cells.<ref name="Leicht Weinig Mayer Viebahn 2018 p. ">{{cite journal | last=Leicht | first=Hans Benno | last2=Weinig | first2=Elke | last3=Mayer | first3=Beate | last4=Viebahn | first4=Johannes | last5=Geier | first5=Andreas | last6=Rau | first6=Monika | title=Ceftriaxone-induced hemolytic anemia with severe renal failure: a case report and review of literature | journal=BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology | publisher=Springer Science and Business Media LLC | volume=19 | issue=1 | date=October 25, 2018 | issn=2050-6511 | doi=10.1186/s40360-018-0257-7 |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6203207/|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Drug-independent autoantibodies are a less common factor in DIIHA. Drug-independent autoantibodies are found in Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia because of [[Β-Lactamase inhibitor|beta-lactamase inhibitors]] and [[Platinum-based chemotherapeutic drug|platinum-based chemotherapeutics]]. These autoantibodies can sometimes bind and react to [[Red blood cell|red blood cells]] even in the absence of whatever drug triggered the [[anemia]].<ref name="Leicht Weinig Mayer Viebahn 2018 p. "/> |

|||

==Diagnosis== |

|||

Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia causes a significant drop in [[hemoglobin]] and [[hematocrit]]. Occasionally DIIHA can present with mild [[leukocytosis]]. In it's earlier stages patients with DIIHA will have low [[Reticulocyte|reticulocytes]]. As HIIHA progresses [[Reticulocyte|reticulocytes]] increase leading to an elevated [[mean corpuscular volume]]. [[Indirect bilirubin]] and [[Lactate dehydrogenase]] become elevated. [[Liver function tests|LFTs]] occasionally become elevated. In some cases, a [[peripheral blood smear]] may show [[Schistocyte|schistocytes]], [[anisocytosis]], [[polychromasia]], or [[poikilocytosis]].<ref name="Karunathilaka Chandrasiri Ranasinghe Ratnamalala 2020 pp. 1–3"/> |

|||

[[Direct antiglobulin test]]ing is the only way to confirm DIIHA. [[Direct antiglobulin test]]ing can determine if [[C3a (complement)|complement C3 antibody]] and/or [[immunoglobulin G]] is bound to the red blood cell membrane.<ref name="Hill Stamps Massey Grainger 2017 pp. 208–220">{{cite journal | last=Hill | first=Quentin A. | last2=Stamps | first2=Robert | last3=Massey | first3=Edwin | last4=Grainger | first4=John D. | last5=Provan | first5=Drew | last6=Hill | first6=Anita | title=Guidelines on the management of drug‐induced immune and secondary autoimmune, haemolytic anaemia | journal=British Journal of Haematology | publisher=Wiley | volume=177 | issue=2 | year=2017 | issn=0007-1048 | doi=10.1111/bjh.14654 | pages=208–220|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.14654|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> A positive direct antiglobulin test differentiates immune-mediated hemolytic anemia from a nonimmune-mediated cause. Other situations such as [[liver disease]], post-[[Blood transfusion|transfusion]] or [[Immunoglobulin therapy|immunoglobulin]] administration, [[renal disease]], and [[malignancy]] can cause a positive direct antiglobulin test.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> If both complement C3 Antibodies and immunoglobulin G are positive or if only immunoglobulin G is positive then [[warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia]] must be considered as a differential diagnosis.<ref name="Hill Stamps Massey Grainger 2017 pp. 208–220"/> |

|||

==Treatment== |

|||

An appropriate course of treatment for drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia hasn't yet been established. Once DIIHA has been recognized, the patient must stop whatever drug caused the anemia in order to provide proper treatment. Patients should be given [[Blood transfusion|blood transfusions]] as needed. The use of [[thromboprophylaxis]] is encouraged because despite being anemic, patients are often [[hypercoagulable]].<ref name="Hill Stamps Massey Grainger 2017 pp. 208–220"/> Although [[Corticosteroid|corticosteroids]] have been used to treat DIIHA it is difficult to differentiate how much effects [[Corticosteroid|corticosteroids]] actually have on DIIHA.<ref name="Garbe Andersohn Bronder Klimpel 2011 pp. 644–653">{{cite journal | last=Garbe | first=Edeltraut | last2=Andersohn | first2=Frank | last3=Bronder | first3=Elisabeth | last4=Klimpel | first4=Andreas | last5=Thomae | first5=Michael | last6=Schrezenmeier | first6=Hubert | last7=Hildebrandt | first7=Martin | last8=Späth‐Schwalbe | first8=Ernst | last9=Grüneisen | first9=Andreas | last10=Mayer | first10=Beate | last11=Salama | first11=Abdulgabar | last12=Kurtal | first12=Hanife | title=Drug induced immune haemolytic anaemia in the Berlin Case‐Control Surveillance Study | journal=British Journal of Haematology | publisher=Wiley | volume=154 | issue=5 | date=July 12, 2011 | issn=0007-1048 | doi=10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08784.x | pages=644–653|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21749359/|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

If drug-independent autoantibodies are involved and stopping the offending agents results in no response then intravenous [[Immunoglobulin therapy|immunoglobulins]] and [[Immunosuppressive drug|immunosuppressants]] such as [[rituximab]], [[azathioprine]], [[cyclophosphamide]], [[cyclosporine]], [[danazol]], and [[mycophenolate]] can be used.<ref name="Leicht Weinig Mayer Viebahn 2018 p. "/><ref name="Wu Wu Ji Liang 2021 p. ">{{cite journal | last=Wu | first=Yuanjun | last2=Wu | first2=Yong | last3=Ji | first3=Yanli | last4=Liang | first4=Jiajie | last5=He | first5=Ziyi | last6=Liu | first6=Yanhui | last7=Tang | first7=Li | last8=Guo | first8=Ganping | title=Case Report: Drug-Induced Immune Haemolytic Anaemia Caused by Cefoperazone-Tazobactam/ Sulbactam Combination Therapy | journal=Frontiers in Medicine | publisher=Frontiers Media SA | volume=8 | date=August 12, 2021 | issn=2296-858X | doi=10.3389/fmed.2021.697192 |url=https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.697192/full|access-date=November 21, 2023|doi-access=free}}</ref> Improvement is typically seen within a few weeks of cessation of the offending drug.<ref name="Chan Gomez Saleem Snyder Joseph 2020 p. "/> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Drug-induced nonautoimmune hemolytic anemia]] |

|||

* [[List of circulatory system conditions]] |

|||

* [[Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia]] |

|||

* [[List of hematologic conditions]] |

|||

* [[Autoimmune hemolytic anemia]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

==Further reading== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{cite journal | last=Chan | first=Maverick | last2=Silverstein | first2=William K. | last3=Nikonova | first3=Anna | last4=Pavenski | first4=Katerina | last5=Hicks | first5=Lisa K. | title=Bendamustine-induced immune hemolytic anemia: a case report and systematic review of the literature | journal=Blood Advances | publisher=American Society of Hematology | volume=4 | issue=8 | date=April 28, 2020 | issn=2473-9529 | doi=10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001726 | pages=1756–1759|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7189296/|doi-access=free|access-date=November 21, 2023|ref=none}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last=Mayer | first=Beate | last2=Bartolmäs | first2=Thilo | last3=Yürek | first3=Salih | last4=Salama | first4=Abdulgabar | title=Variability of Findings in Drug-Induced Immune Haemolytic Anaemia: Experience over 20 Years in a Single Centre | journal=Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy | publisher=S. Karger AG | volume=42 | issue=5 | year=2015 | issn=1660-3796 | doi=10.1159/000440673 | pages=333–339|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4678312/|doi-access=free|access-date=November 21, 2023|ref=none}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last=Salama | first=Abdulgabar | title=Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia | journal=Expert Opinion on Drug Safety | publisher=Informa UK Limited | volume=8 | issue=1 | year=2009 | issn=1474-0338 | doi=10.1517/14740330802577351 | pages=73–79|url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1517/14740330802577351|access-date=November 21, 2023|ref=none}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Medical resources |

{{Medical resources |

||

| |

| ICD11 = {{ICD11|3A20.Y}} |

||

| |

| ICD10 = {{ICD10|D59.0}} |

||

| |

| ICD10CM = <!-- {{ICD10CM|Xxx.xxxx}} --> |

||

| |

| ICD9 = {{ICD9|283}} |

||

| |

| ICDO = |

||

| |

| OMIM = |

||

| |

| MeshID = |

||

| DiseasesDB = |

|||

| eMedicineTopic = |

|||

| |

| SNOMED CT = 309742004 |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| MedlinePlus = 000578 |

|||

| eMedicineSubj = |

|||

| eMedicineTopic = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| GeneReviewsNBK = |

|||

| GeneReviewsName = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| RP = |

|||

| AO = |

|||

| WO = |

|||

| OrthoInfo = |

|||

| Orphanet = 90037 |

|||

| Scholia = Q5308809 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Diseases of RBCs}} |

{{Diseases of RBCs}} |

||

[[Category:Acquired hemolytic anemia]] |

[[Category:Acquired hemolytic anemia]] |

||

[[Category:Drug-induced diseases]] |

[[Category:Drug-induced diseases]] |

||

{{Blood-disease-stub|}} |

|||

Revision as of 03:49, 22 November 2023

| Drug-induced autoimmune heamolytic anemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia, DIIHA. |

| |

| Blood smear from a patient with warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia showing spherocytes, marked polychromasia and a nucleated red blood cell. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness, bloody urine, jaundice, weakness, and palpitations[1] |

| Complications | Hemolysis, shock, ischemia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation,[1] and acute renal failure.[2] |

| Usual onset | Hours to months of the initial drug exposure.[1] |

| Causes | Antimicrobials, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antineoplastic drugs, and other drugs.[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, blood smear, and Direct antiglobulin testing[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia.[4] |

| Treatment | Stopping the offending drug, blood transfusions, and thromboprophylaxis.[4] |

| Frequency | One to two people per million worldwide.[1] |

Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia also known as Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia (DIIHA) is a rare cause of hemolytic anemia. It is difficult to differentiate from other forms of anemia which can lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Many different types of antibiotics can cause DIIHA and discontinuing the offending medication is the first line of treatment. DIIHA has is estimated to affect one to two people per million worldwide.[1]

In some cases, a drug can cause the immune system to mistakenly think the body's own red blood cells are dangerous, foreign substances. Antibodies then develop against the red blood cells. The antibodies attach to red blood cells and cause them to break down too early. It is known that more than 150 drugs can cause this type of hemolytic anemia.[5] The list includes:

- Cephalosporins (a class of antibiotics)

- Dapsone

- Levodopa

- Levofloxacin

- Methyldopa

- Nitrofurantoin

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) - among them, the commonly used Diclofenac and Ibuprofen

- Phenazopyridine (pyridium)

- Quinidine[6]

Signs and symptoms

Initial symptoms of drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia are typically vague and reflect mild, moderate, or severe anemia. Symptoms of DIIHA can manifest within hours to months of the initial drug exposure.[1] DIIHA ranges in severity from severe intravascular hemolysis to milder presentations of extravascular hemolysis.[7] Common symptoms of DIIHA are fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness, bloody or dark urine,[1] weakness, and palpitations. DIIHA will occasionally present as hemoglobinuria with chills, however this is quite rare.[2] Patients with DIIHA may appear pale and have jaundice. Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and adenopathy have also been observed.[1]

When DIIHA is not recognized promptly it can have life-threatening complications such as hemolysis leading to shock, ischemia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation,[1] and acute renal failure.[2]

Causes

As of 2020 over 130 drugs have been reported to cause DIIHA. That number will continue to rise as new drugs are discovered.[1] Antimicrobials are responsible for 42% of DIIHA cases, making them the most common cause. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs cause about 15% of cases and antineoplastic drugs cause around 11%.[3]

Mechanism

The main mechanism of DIIHA is the development of antibodies. Drug-induced antibodies can be classified into two groups, drug-dependent antibodies and drug-independent autoantibodies. Drug-dependent antibodies are common in DIIHA. They require the offending drug to be present in order to bind and lyse cells.[8]

Drug-independent autoantibodies are a less common factor in DIIHA. Drug-independent autoantibodies are found in Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia because of beta-lactamase inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapeutics. These autoantibodies can sometimes bind and react to red blood cells even in the absence of whatever drug triggered the anemia.[8]

Diagnosis

Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia causes a significant drop in hemoglobin and hematocrit. Occasionally DIIHA can present with mild leukocytosis. In it's earlier stages patients with DIIHA will have low reticulocytes. As HIIHA progresses reticulocytes increase leading to an elevated mean corpuscular volume. Indirect bilirubin and Lactate dehydrogenase become elevated. LFTs occasionally become elevated. In some cases, a peripheral blood smear may show schistocytes, anisocytosis, polychromasia, or poikilocytosis.[7]

Direct antiglobulin testing is the only way to confirm DIIHA. Direct antiglobulin testing can determine if complement C3 antibody and/or immunoglobulin G is bound to the red blood cell membrane.[4] A positive direct antiglobulin test differentiates immune-mediated hemolytic anemia from a nonimmune-mediated cause. Other situations such as liver disease, post-transfusion or immunoglobulin administration, renal disease, and malignancy can cause a positive direct antiglobulin test.[1] If both complement C3 Antibodies and immunoglobulin G are positive or if only immunoglobulin G is positive then warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia must be considered as a differential diagnosis.[4]

Treatment

An appropriate course of treatment for drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia hasn't yet been established. Once DIIHA has been recognized, the patient must stop whatever drug caused the anemia in order to provide proper treatment. Patients should be given blood transfusions as needed. The use of thromboprophylaxis is encouraged because despite being anemic, patients are often hypercoagulable.[4] Although corticosteroids have been used to treat DIIHA it is difficult to differentiate how much effects corticosteroids actually have on DIIHA.[9]

If drug-independent autoantibodies are involved and stopping the offending agents results in no response then intravenous immunoglobulins and immunosuppressants such as rituximab, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, danazol, and mycophenolate can be used.[8][10] Improvement is typically seen within a few weeks of cessation of the offending drug.[1]

See also

- Drug-induced nonautoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Chan Gomez, Janet; Saleem, Tabinda; Snyder, Samantha; Joseph, Maria; Kanderi, Tejaswi (June 17, 2020). "Drug-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia due to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate: A Case Report and Review". Cureus. Cureus, Inc. doi:10.7759/cureus.8666. ISSN 2168-8184. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c Chen, Fei; Zhan, Zhuying. "Severe drug-induced immune haemolytic anaemia due to ceftazidime". Blood Transfusion. Edizioni SIMTI. doi:10.2450/2014.0237-13. PMID 24887228. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Garratty, George (January 1, 2009). "Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia". Hematology. 2009 (1). American Society of Hematology: 73–79. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.73. ISSN 1520-4391. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Hill, Quentin A.; Stamps, Robert; Massey, Edwin; Grainger, John D.; Provan, Drew; Hill, Anita (2017). "Guidelines on the management of drug‐induced immune and secondary autoimmune, haemolytic anaemia". British Journal of Haematology. 177 (2). Wiley: 208–220. doi:10.1111/bjh.14654. ISSN 0007-1048. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Barcellini, Wilma (2015-10-01). "Immune Hemolysis: Diagnosis and Treatment Recommendations". Seminars in Hematology. Anemia in Clinical Practice. 52 (4): 304–312. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.05.001. ISSN 0037-1963. PMID 26404442.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia

- ^ a b Karunathilaka, H. G. C. S.; Chandrasiri, D. P.; Ranasinghe, P.; Ratnamalala, V.; Fernando, A. H. N. (March 31, 2020). "Co-Amoxiclav Induced Immune Haemolytic Anaemia: A Case Report". Case Reports in Hematology. 2020. Hindawi Limited: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2020/9841097. ISSN 2090-6560. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c Leicht, Hans Benno; Weinig, Elke; Mayer, Beate; Viebahn, Johannes; Geier, Andreas; Rau, Monika (October 25, 2018). "Ceftriaxone-induced hemolytic anemia with severe renal failure: a case report and review of literature". BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology. 19 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. doi:10.1186/s40360-018-0257-7. ISSN 2050-6511. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Garbe, Edeltraut; Andersohn, Frank; Bronder, Elisabeth; Klimpel, Andreas; Thomae, Michael; Schrezenmeier, Hubert; Hildebrandt, Martin; Späth‐Schwalbe, Ernst; Grüneisen, Andreas; Mayer, Beate; Salama, Abdulgabar; Kurtal, Hanife (July 12, 2011). "Drug induced immune haemolytic anaemia in the Berlin Case‐Control Surveillance Study". British Journal of Haematology. 154 (5). Wiley: 644–653. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08784.x. ISSN 0007-1048. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Wu, Yuanjun; Wu, Yong; Ji, Yanli; Liang, Jiajie; He, Ziyi; Liu, Yanhui; Tang, Li; Guo, Ganping (August 12, 2021). "Case Report: Drug-Induced Immune Haemolytic Anaemia Caused by Cefoperazone-Tazobactam/ Sulbactam Combination Therapy". Frontiers in Medicine. 8. Frontiers Media SA. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.697192. ISSN 2296-858X. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

Further reading

- Chan, Maverick; Silverstein, William K.; Nikonova, Anna; Pavenski, Katerina; Hicks, Lisa K. (April 28, 2020). "Bendamustine-induced immune hemolytic anemia: a case report and systematic review of the literature". Blood Advances. 4 (8). American Society of Hematology: 1756–1759. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001726. ISSN 2473-9529. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- Mayer, Beate; Bartolmäs, Thilo; Yürek, Salih; Salama, Abdulgabar (2015). "Variability of Findings in Drug-Induced Immune Haemolytic Anaemia: Experience over 20 Years in a Single Centre". Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 42 (5). S. Karger AG: 333–339. doi:10.1159/000440673. ISSN 1660-3796. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- Salama, Abdulgabar (2009). "Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 8 (1). Informa UK Limited: 73–79. doi:10.1517/14740330802577351. ISSN 1474-0338. Retrieved November 21, 2023.