Sarcoidosis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

added |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

<!-- Epidemiology and history --> |

<!-- Epidemiology and history --> |

||

In the United States, the disease most commonly affects people of Northern European (especially Scandinavian or Icelandic) or African/African American, although any race or age group may be affected.<ref name = MSR/> Japan has a lower rate of sarcoidosi although the disease is usually more aggressive with the heart often affected.<ref name = MSR/> It usually begins between the ages of 20–50.<ref name=NIH2013Risk/> It occurs more often in women than men.<ref name=NIH2013Risk>{{cite web|title=Who Is at Risk for Sarcoidosis?|url=http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sarc/atrisk|website=NHLBI|accessdate=28 March 2016|date=June 14, 2013}}</ref> Sarcoidosis was first described in 1877 by the English doctor [[Jonathan Hutchinson]] as a skin disease causing red, raised lesions on the arms, face, and hands.<ref name = hutch>{{cite journal | author = James DG, Sharma OP | title = From Hutchinson to now: a historical glimpse | journal = Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine | volume = 8 | issue = 5 | pages = 416–23 | date = September 2002 | pmid = 12172446 | doi = 10.1097/01.MCP.0000020256.35153.12 | url = http://www.ildcare.eu/Downloads/artseninfo/History_of_sarcoidosis.pdf | format = PDF | last2 = Sharma | doi_brokendate = 2015-02-01 }}</ref> |

In 2013 pulmonary sarcoidosis and [[interstitial lung disease]] affected 595,000 people globally.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Global Burden of Disease Study 2013|first1=Collaborators|title=Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.|journal=Lancet (London, England)|date=22 August 2015|volume=386|issue=9995|pages=743-800|pmid=26063472}}</ref> In the United States, the disease most commonly affects people of Northern European (especially Scandinavian or Icelandic) or African/African American, although any race or age group may be affected.<ref name = MSR/> Japan has a lower rate of sarcoidosi although the disease is usually more aggressive with the heart often affected.<ref name = MSR/> It usually begins between the ages of 20–50.<ref name=NIH2013Risk/> It occurs more often in women than men.<ref name=NIH2013Risk>{{cite web|title=Who Is at Risk for Sarcoidosis?|url=http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sarc/atrisk|website=NHLBI|accessdate=28 March 2016|date=June 14, 2013}}</ref> Sarcoidosis was first described in 1877 by the English doctor [[Jonathan Hutchinson]] as a skin disease causing red, raised lesions on the arms, face, and hands.<ref name = hutch>{{cite journal | author = James DG, Sharma OP | title = From Hutchinson to now: a historical glimpse | journal = Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine | volume = 8 | issue = 5 | pages = 416–23 | date = September 2002 | pmid = 12172446 | doi = 10.1097/01.MCP.0000020256.35153.12 | url = http://www.ildcare.eu/Downloads/artseninfo/History_of_sarcoidosis.pdf | format = PDF | last2 = Sharma | doi_brokendate = 2015-02-01 }}</ref> |

||

==Signs and symptoms== |

==Signs and symptoms== |

||

Revision as of 08:38, 29 March 2016

| Sarcoidosis | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Hematology, dermatology, pulmonology, ophthalmology |

| Frequency | 0.16% |

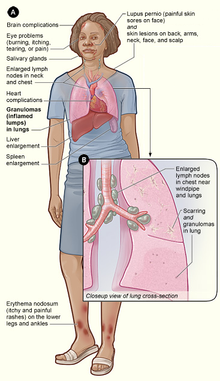

Sarcoidosis, also called sarcoid, is a disease involving abnormal collections of inflammatory cells (granulomas) that can form as nodules in multiple organs.[1] The disease usually begins in the lungs, skin, or lymph nodes.[2] Any organ; however, can be affected.[2] The signs and symptoms depends on the organ affected.[2] Often there or no or only mild symptoms.[2] Some may have Lofgren's syndrome in which there is fever, large lymph nodes, arthritis, and a rash known as erythema nodosum.[2]

The cause of sarcoidosis is unknown.[2] Some believe it be due to may be due to an immune reaction to a trigger such as an infection or chemicals in those who are genetically predisposed.[3][4] Those with affected family members are at greater risk.[5] Elevated calcitriol is the main cause for high blood calcium in sarcoidosis and is overproduced by sarcoid granulomata. Gamma-interferon produced by activated lymphocytes and macrophages plays a major role in the synthesis of calcitriol. In developing countries, it often goes misdiagnosed as tuberculosis (TB), as its symptoms often resemble those of TB.[6]

Many people clear up without any treatment within a few years.[2] Some cases affect a person long-term or become life-threatening and require medical intervention.[7] Treatment may be given to help relieve the symptoms with the use of anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen or aspirin.[8] In cases where the condition develops to the point that it has a progressive and/or life-threatening course, treatment is most often with steroid such as prednisone.[8] Alternatively, drugs such as methotrexate, azathioprine and leflunomide may be used.[8][9][10] The average mortality rate is less than 5% in untreated cases.[6] There is a less than 5% chance of the disease requiring in someone who has had it previously.[2]

In 2013 pulmonary sarcoidosis and interstitial lung disease affected 595,000 people globally.[11] In the United States, the disease most commonly affects people of Northern European (especially Scandinavian or Icelandic) or African/African American, although any race or age group may be affected.[6] Japan has a lower rate of sarcoidosi although the disease is usually more aggressive with the heart often affected.[6] It usually begins between the ages of 20–50.[5] It occurs more often in women than men.[5] Sarcoidosis was first described in 1877 by the English doctor Jonathan Hutchinson as a skin disease causing red, raised lesions on the arms, face, and hands.[12]

Signs and symptoms

Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease that can affect any organ, although it can be asymptomatic and is discovered by accident in about 5% of cases.[14] Common symptoms, which tend to be vague, include fatigue (unrelieved by sleep; occurs in 66% of cases), lack of energy, weight loss, joint aches and pains (which occur in about 70% of cases),[9] arthritis (14–38% of persons), dry eyes, swelling of the knees, blurry vision, shortness of breath, a dry, hacking cough, or skin lesions.[1][15][16][17] Less commonly, people may cough up blood.[1] The cutaneous symptoms vary, and range from rashes and noduli (small bumps) to erythema nodosum, granuloma annulare, or lupus pernio. Sarcoidosis and cancer may mimic one another, making the distinction difficult.[18]

The combination of erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and joint pain is called Löfgren syndrome, which has a relatively good prognosis.[1] This form of the disease occurs significantly more often in Scandinavian patients than in those of non-Scandinavian origin.[6]

Respiratory tract

Localization to the lungs is by far the most common manifestation of sarcoidosis.[19] At least 90% of affected persons experience lung involvement.[7] Overall, about 50% develop permanent pulmonary abnormalities, and 5 to 15% have progressive fibrosis of the lung parenchyma. Sarcoidosis of the lung is primarily an interstitial lung disease in which the inflammatory process involves the alveoli, small bronchi and small blood vessels.[20] In acute and subacute cases, physical examination usually reveals dry crackles.[7] At least 5% of persons will suffer pulmonary arterial hypertension.[7][21] Less commonly, the upper respiratory tract (including the larynx, pharynx, and sinuses) may be affected, which occurs in between 5 and 10% of cases.[22]

Sarcoidosis of the lungs can be divided into four stages:

- Stage 0 — No intrathoracic involvement.

- Stage I — Bilateral hilar adenopathy.

- Stage II — Pulmonary parenchyma involved.

- Stage III — Pulmonary infiltrates with fibrosis.[7]

- Stage 4 is end-stage lung disease with pulmonary fibrosis and honeycombing.[23]

Skin

Sarcoidosis involves the skin in between 9 and 37% of persons and is more common in African Americans than in European Americans.[7] The skin is the second most commonly affected organ after the lungs.[24] The most common lesions are erythema nodosum, plaques, maculopapular eruptions, subcutaneous nodules, and lupus pernio.[24] Treatment is not required, since the lesions usually resolve spontaneously in two to four weeks. Although it may be disfiguring, cutaneous sarcoidosis rarely causes major problems.[7][25][26] Sarcoidosis of the scalp presents with diffuse or patchy hair loss.[27][28]

Heart

The frequency of cardiac involvement varies and is significantly influenced by race; in Japan more than 25% of persons with sarcoidosis have symptomatic cardiac involvement, whereas in the US and Europe only about 5% of cases present with cardiac involvement.[7] Autopsy studies in the US have revealed a frequency of cardiac involvement of about 20–30%, whereas autopsy studies in Japan have shown a frequency of 60%.[16] The presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis can range from asymptomatic conduction abnormalities to fatal ventricular arrhythmia.[29] Conduction abnormalities are the most common cardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis in humans and can include complete heart block.[30] Second to conduction abnormalities, in frequency, are ventricular arrhythmias, which occurs in about 23% of persons with cardiac involvement.[30] Sudden cardiac death, either due to ventricular arrhythmias or complete heart block is a rare complication of cardiac sarcoidosis.[31][32] Cardiac sarcoidosis can cause fibrosis, granuloma formation, or the accumulation of fluid in the interstitium of the heart, or a combination of the former two.[33]

Eye

Eye involvement occurs in about 10–90% of cases.[16] Manifestations in the eye include uveitis, uveoparotitis, and retinal inflammation, which may result in loss of visual acuity or blindness.[34] The most common ophthalmologic manifestation of sarcoidosis is uveitis.[16][35] The combination of anterior uveitis, parotitis, VII cranial nerve paralysis and fever is called uveoparotid fever or Heerfordt syndrome (D86.8). Development of scleral nodule associated with sarcoidosis has been observed.[36]

Nervous system

Any of the components of the nervous system can be involved.[37] Sarcoidosis affecting the nervous system is known as neurosarcoidosis.[37] Cranial nerves are most commonly affected, accounting for about 5–30% of neurosarcoidosis cases, and peripheral facial nerve palsy, often bilateral, is the most common neurological manifestation of sarcoidosis.[37][38][39] It occurs suddenly and is usually transient. The central nervous system involvement is present in 10–25% of sarcoidosis cases.[22] Other common manifestations of neurosarcoid include optic nerve dysfunction, papilledema, palate dysfunction, neuroendocrine changes, hearing abnormalities, hypothalamic and pituitary abnormalities, chronic meningitis, and peripheral neuropathy.[7] Myelopathy, that is spinal cord involvement, occurs in about 16–43% of neurosarcoidosis cases and is often associated with the poorest prognosis of the neurosarcoidosis subtypes.[37] Whereas facial nerve palsies and acute meningitis due to sarcoidosis tends to have the most favourable prognosis.[37] Another common finding in sarcoidosis with neurological involvement is autonomic or sensory small fiber neuropathy.[40][41] Neuroendocrine sarcoidosis accounts for about 5–10% of neurosarcoidosis cases and can lead to diabetes insipidus, changes in menstrual cycle and hypothalamic dysfunction.[37][39] The latter can lead to changes in body temperature, mood and prolactin (see the endocrine and exocrine section for details).[37]

Endocrine and exocrine

Prolactin is frequently increased in sarcoidosis, between 3% and 32% of cases have hyperprolactinemia[42] this frequently leads to amenorrhea, galactorrhea, or nonpuerperal mastitis in women. It also frequently causes an increase in 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, the active metabolite of vitamin D, which is usually hydrolysed within the kidney, but in sarcoidosis patients hydroxylation of vitamin D can occur outside the kidneys, namely inside the immune cells found in the granulomas the condition produces. 1 alpha, 25(OH)2D3 is the main cause for hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis and overproduced by sarcoid granulomata. Gamma-interferon produced by activated lymphocytes and macrophages plays a major role in the synthesis of 1 alpha, 25(OH)2D3. [43] Hypercalciuria (excessive secretion of calcium in one's urine) and hypercalcemia (an excessively high amount of calcium in the blood) are seen in <10% of individuals and likely results from the increased 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D production.[44] Thyroid dysfunction is seen in 4.2–4.6% of cases.[45][46]

Parotid enlargement occurs in about 5–10% of persons.[9] Bilateral involvement is the rule. The gland is usually not tender, but firm and smooth. Dry mouth can occur; other exocrine glands are affected only rarely.[7] The eyes, their glands, or the parotid glands are affected in 20%-50% of cases.[47]

Gastrointestinal and genitourinary

Symptomatic GI involvement occurs in less than 1% of persons (note that this is if one excludes the liver), and most commonly the stomach is affected, although the small or large intestine may also be affected in a small portion of cases.[9][48] Studies at autopsy have revealed GI involvement in less than 10% of people.[39] These cases would likely mimic Crohn's disease, which is a more commonly intestine-affecting granulomatous disease.[9] About 1–3% of people have evidence of pancreatic involvement at autopsy.[39] Symptomatic kidney involvement occurs in just 0.7% of cases, although evidence of kidney involvement at autopsy has been reported in up to 22% of people and occurs exclusively in cases of chronic disease.[9][16][39] Symptomatic kidney involvement is usually nephrocalcinosis, although granulomatous interstitial nephritis that presents with reduced creatinine clearance and little proteinuria is a close second.[9][39] Less commonly, the epididymis, testicles, prostate, ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, or the vulva may be affected, the latter may cause vulva itchiness.[16][49][50] Testicular involvement has been reported in about 5% of people at autopsy.[39][50] In males, sarcoidosis may lead to infertility.[51]

Around 70% of people have granulomas in their livers, although only in about 20–30% of cases liver function test anomalies reflecting this fact are seen.[1][7] About 5–15% of persons exhibit hepatomegaly, that is an enlarged liver.[16] Only 5–30% of cases of liver involvement are symptomatic.[52] Usually, these changes reflect a cholestatic pattern and include raised levels of alkaline phosphatase (which is the most common liver function test anomaly seen in persons with sarcoidosis), while bilirubin and aminotransferases are only mildly elevated. Jaundice is rare.[7][9]

Blood

Abnormal blood tests are frequent, accounting for over 50% of cases, but is not diagnostic.[7][22] Lymphopenia is the most common blood anomaly in sarcoidosis.[7] Anemia occurs in about 20% of people with sarcoidosis.[7] Leukopenia is less common and occurs in even fewer persons but is rarely severe.[7] Thrombocytopenia and hemolytic anemia are fairly rare.[9] In the absence of splenomegaly, leukopenia may reflect bone marrow involvement, but the most common mechanism is a redistribution of blood T cells to sites of disease.[53] Other nonspecific findings include monocytosis, occurring in the majority of sarcoidosis cases,[54] increased hepatic enzymes or alkaline phosphatase. People with sarcoidosis often have immunologic anomalies like allergies to test antigens such as Candida or purified protein derivative (PPD).[47] Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia is also a fairly common immunologic anomaly seen in sarcoidosis.[47]

Lymphadenopathy (swollen glands) is common in sarcoidosis and occurs in 15% of cases.[17] Intrathoracic nodes are enlarged in 75 to 90% of all people; usually this involves the hilar nodes, but the paratracheal nodes are commonly involved. Peripheral lymphadenopathy is very common, particularly involving the cervical (the most common head and neck manifestation of the disease), axillary, epitrochlear, and inguinal nodes.[55] Approximately 75% of cases show microscopic involvement of the spleen, although only in about 5–10% of cases does splenomegaly appear.[9][47]

Bone, joints, and muscles

Sarcoidosis can be involved with the joints, bones and muscles. This causes a wide variety of musculoskeletal complaints that act through different mechanisms.[56] About 5–15% of cases affect the bones, joints, or muscles.[22]

Arthritic syndromes can be categorized in two ways: as acute or chronic.[56] Sarcoidosis patients suffering acute arthritis often also have bilateral Hilar lymphadenopathy and Erythema nodosum. These three associated syndromes often occur together in Löfgren syndrome.[56] The arthritis symptoms of Löfgren syndrome occur most frequently in the ankles, followed by the knees, wrists, elbows, wrists, and metacarpophalangeal joints.[56] Usually true arthritis is not present, but instead periarthritis appears as a swelling in the soft tissue around the joints that can be seen by ultrasonographic methods. [56] These joint symptoms tend to precede or occur at the same time as erythema nodosum develops.[56] Even when erythema nodosum is absent, it is believed that the combination of hilar lymphadenopathy and ankle periarthritis van be considered as a variant of Löfgren syndrome.[56] Enthesitis also occurs in about one-third of patients with acute sarcoid arthritis, mainly affecting the Achilles tendon and heels.[56] Soft tissue swelling at the ankles can be prominent, and biopsy of this soft tissue reveals no granulomas but does show panniculitis that is similar to erythema nodosum.[56]

Chronic sarcoid arthritis usually occurs in the setting of more diffuse organ involvement. [56] The ankles, knees, wrists, elbows, and hands may all be affected in the chronic form and often this presents itself in a polyarticular pattern.[56] Dactylitis similar to that seen in Psoriatic arthritis, that is associated with pain, swelling, overlying skin erythema, and underlying bony changes may also occur.[56] Development of Jaccoud arthropathy (a nonerosive deformity) is very rarely seen.[56]

Bone involvement in sarcoidosis has been reported in 1–13% of cases.[39] The most frequent sites of involvement are the hands and feet, whereas the spine is less commonly affected.[56] Half of the patients with bony lesions experience pain and stiffness, whereas the other half remain asymptomatic.[56] Periostitis is rarely seen in Sarcoidosis and has been found to present itself at the femoral bone.[57][58]

Cause

The exact cause of sarcoidosis is not known.[2] The current working hypothesis is, in genetically susceptible individuals, sarcoidosis is caused through alteration to the immune response after exposure to an environmental, occupational, or infectious agent.[59] Some cases may be caused by treatment with TNF inhibitors like etanercept.[60]

Genetics

The heritability of sarcoidosis varies according to race, about 20% of African Americans with sarcoidosis have a family member with the condition, whereas the same figure for whites is about 5%.[6] Investigations of genetic susceptibility yielded many candidate genes, but only few were confirmed by further investigations and no reliable genetic markers are known. Currently, the most interesting candidate gene is BTNL2; several HLA-DR risk alleles are also being investigated.[61][62] In persistent sarcoidosis, the HLA haplotype HLA-B7-DR15 are either cooperating in disease or another gene between these two loci is associated. In nonpersistent disease, there is a strong genetic association with HLA DR3-DQ2.[63][64] Cardiac sarcoid has been connected to TNFA variants.[65]

Infectious agents

Several infectious agents appear to be significantly associated with sarcoidosis, but none of the known associations is specific enough to suggest a direct causative role.[66] The major implicated infectious agents include: mycobacteria, fungi, borrelia, and rickettsia.[67] A recent meta-analysis investigating the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis found it was present in 26.4% of cases, but the meta-analysis also detected a possible publication bias, so the results need further confirmation.[68][69] Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase-peroxidase has been identified as a possible antigen catalyst of sarcoidosis.[70] The disease has also been reported by transmission via organ transplants.[71]

Autoimmune

Association of autoimmune disorders has been frequently observed. The exact mechanism of this relation is not known, but some evidence supports the hypothesis that this is a consequence of Th1 lymphokine prevalence.[45][72] Tests of delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity have been used to measure progression.[73]

Pathophysiology

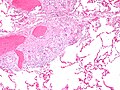

Granulomatous inflammation is characterized primarily by accumulation of monocytes, macrophages, and activated T-lymphocytes, with increased production of key inflammatory mediators, TNF, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18, IL-23 and TGF-β, indicative of a Th1-mediated immune response.[67][74] Sarcoidosis has paradoxical effects on inflammatory processes; it is characterized by increased macrophage and CD4 helper T-cell activation, resulting in accelerated inflammation, but immune response to antigen challenges such as tuberculin is suppressed. This paradoxic state of simultaneous hyper- and hypoactivity is suggestive of a state of anergy. The anergy may also be responsible for the increased risk of infections and cancer.

The regulatory T-lymphocytes in the periphery of sarcoid granulomas appear to suppress IL-2 secretion, which is hypothesized to cause the state of anergy by preventing antigen-specific memory responses.[75] Schaumann bodies seen in sarcoidosis are calcium and protein inclusions inside of Langhans giant cells as part of a granuloma.

While TNF is widely believed to play an important role in the formation of granulomas (which is further supported by the finding that in animal models of mycobacterial granuloma formation inhibition of either TNF or IFN-γ production inhibits granuloma formation), sarcoidosis can and does still develop in persons being treated with TNF antagonists like etanercept.[76] B cells also likely play a role in the pathophysiology of sarcoidosis.[6] Serum levels of soluble HLA class I antigens and ACE are higher in persons with sarcoidosis.[6] Likewise the ratio of CD4/CD8 T cells in bronchoalveolar lavage is usually higher in persons with pulmonary sarcoidosis (usually >3.5), although it can be normal or even abnormally low in some cases.[6] Serum ACE levels have been found to usually correlate with total granuloma load.[67]

Cases of sarcoidosis have also been reported as part of the immune reconstitution syndrome of HIV, that is, when people receive treatment for HIV their immune system rebounds and the result is that it starts to attack the antigens of opportunistic infections caught prior to said rebound and the resulting immune response starts to damage healthy tissue.[74]

-

Sarcoidosis in a lymph node

-

Asteroid body in sarcoidosis

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is a matter of exclusion, as there is no specific test for the condition. To exclude sarcoidosis in a case presenting with pulmonary symptoms might involve chest X-ray, CT scan of chest, PET scan, CT-guided biopsy, mediastinoscopy, open lung biopsy, bronchoscopy with biopsy, endobronchial ultrasound, and endoscopic ultrasound with FNA of mediastinal lymph nodes (EBUS FNA). Tissue from biopsy of lymph nodes is subjected to both flow cytometry to rule out cancer and special stains (acid fast bacilli stain and Gömöri methenamine silver stain) to rule out microorganisms and fungi.[77][78][79][80]

Serum markers of sarcoidosis, include: serum amyloid A, soluble interleukin 2 receptor, lysozyme, angiotensin converting enzyme, and the glycoprotein KL-6.[81] Angiotensin-converting enzyme blood levels are used in the monitoring of sarcoidosis.[81] A bronchoalveolar lavage can show an elevated (of at least 3.5) CD4/CD8 T cell ratio, which is indicative (but not proof) of pulmonary sarcoidosis.[6] In at least one study the induced sputum ratio of CD4/CD8 and level of TNF was correlated to those in the lavage fluid.[81]

Differential diagnosis includes metastatic disease, lymphoma, septic emboli, rheumatoid nodules, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, varicella infection, tuberculosis, and atypical infections, such as Mycobacterium avium complex, cytomegalovirus, and cryptococcus.[82] Sarcoidosis is confused most commonly with neoplastic diseases, such as lymphoma, or with disorders characterized also by a mononuclear cell granulomatous inflammatory process, such as the mycobacterial and fungal disorders.[7]

Chest X-ray changes are divided into four stages:[83]

- Stage 1: bihilar lymphadenopathy

- Stage 2: bihilar lymphadenopathy and reticulonodular infiltrates

- Stage 3: bilateral pulmonary infiltrates

- Stage 4: fibrocystic sarcoidosis typically with upward hilar retraction, cystic and bullous changes

Although people with stage 1 X-rays tend to have the acute or subacute, reversible form of the disease, those with stages 2 and 3 often have the chronic, progressive disease; these patterns do not represent consecutive "stages" of sarcoidosis. Thus, except for epidemiologic purposes, this X-ray categorization is mostly of historic interest.[7]

In sarcoidosis presenting in the Caucasian population, hilar adenopathy and erythema nodosum are the most common initial symptoms. In this population, a biopsy of the gastrocnemius muscle is a useful tool in correctly diagnosing the person. The presence of a noncaseating epithelioid granuloma in a gastrocnemius specimen is definitive evidence of sarcoidosis, as other tuberculoid and fungal diseases extremely rarely present histologically in this muscle.[84]

Classification

Sarcoidosis may be divided into the following types:[27]

Treatment

Most persons (>75%) only require symptomatic treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or aspirin.[8] For persons presenting with lung symptoms, unless the respiratory impairment is devastating, active pulmonary sarcoidosis is observed usually without therapy for two to three months; if the inflammation does not subside spontaneously, therapy is instituted.[7] Corticosteroids, most commonly prednisone or prednisolone, have been the standard treatment for many years.[9] In some people, this treatment can slow or reverse the course of the disease, but other people do not respond to steroid therapy. The use of corticosteroids in mild disease is controversial because in many cases the disease remits spontaneously.[85] Despite their widespread use, the evidence supporting corticosteroid use is weak at best.[86]

Severe symptoms are generally treated with corticosteroids although steroid-sparing agents such as azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolic acid, and leflunomide[87][88] are often used as alternatives.[9][10] Of these, methotrexate is most widely used and studied.[10][89] Methotrexate is considered a first-line treatment in neurosarcoidosis, often in conjunction with corticosteroids.[10][37] Long-term treatment with methotrexate is associated with liver damage in about 10% of people and hence may be a significant concern in people with liver involvement and requires regular liver function test monitoring.[9] Methotrexate can also lead to pulmonary toxicity (lung damage), although this is fairly uncommon and more commonly it can confound the leukopenia caused by sarcoidosis.[9] Due to these safety concerns it is often recommended that methotrexate is combined with folic acid in order to prevent toxicity.[9] Azathioprine treatment can also lead to liver damage.[89] Leflunomide is being used as a replacement for methotrexate, possibly due to its purportedly lower rate of pulmonary toxicity.[89] Mycophenolic acid has been used successfully in uveal sarcoidosis,[90] neurosarcoidosis (especially CNS sarcoidosis; minimally effective in sarcoidosis myopathy),[91] and pulmonary sarcoidosis.[92][93]

As the granulomas are caused by collections of immune system cells, particularly T cells, there has been some success using immunosuppressants (like cyclophosphamide, cladribine,[94] chlorambucil, and cyclosporine), immunomodulatory (pentoxifylline and thalidomide), and anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment[95][96] (such as infliximab, etanercept, golimumab, and adalimumab).[8][97][98]

In a clinical trial cyclosporine added to prednisone treatment failed to demonstrate any significant benefit over prednisone alone in people with pulmonary sarcoidosis, although there was evidence of increased toxicity from the addition of cyclosporine to the steroid treatment including: infections, malignancies (cancers), hypertension, and kidney dysfunction.[89] Likewise chlorambucil and cyclophosphamide are seldom used in the treatment of sarcoidosis due to their high degree of toxicity, especially their potential for causing malignancies.[99] Infliximab has been used successfully to treat pulmonary sarcoidosis in clinical trials in a number of persons.[89] Etanercept, on the other hand, has failed to demonstrate any significant efficacy in people with uveal sarcoidosis in a couple of clinical trials.[89] Likewise golimumab has failed to show any benefit in persons with pulmonary sarcoidosis.[89] One clinical trial of adalimumab found treatment response in about half of subjects, which is similar to that seen with infliximab, but as adalimumab has better tolerability profile it may be preferred over infliximab.[89]

Ursodeoxycholic acid has been used successfully as a treatment for cases with liver involvement.[100] Thalidomide has also been tried successfully as a treatment for treatment-resistant lupus pernio in a clinical trial, which may stem from its anti-TNF activity, although it failed to exhibit any efficacy in a pulmonary sarcoidosis clinical trial.[74][97] Cutaneous disease may be successfully managed with antimalarials (such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine) and the tetracycline antibiotic, minocycline.[7][97] Antimalarials have also demonstrated efficacy in treating sarcoidosis-induced hypercalcemia and neurosarcoidosis.[9] Long-term use of antimalarials is limited, however, by their potential to cause irreversible blindness and hence the need for regular ophthalmologic screening.[99] This toxicity is usually less of a problem with hydroxychloroquine than with chloroquine, although hydroxychloroquine can disturb the glucose homeostasis.[99]

Recently selective phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors like apremilast (a thalidomide derivative), roflumilast, and the less subtype-selective PDE4 inhibitor, pentoxifylline, have been tried as a treatment for sarcoidosis, with successful results being obtained with apremilast in cutaneous sarcoidosis in a small open-label study.[101][102] Pentoxifylline has been used successfully to treat acute disease although its use is greatly limited by its gastrointestinal toxicity (mostly nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea).[88][89][99] Case reports have supported the efficacy of rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and a clinical trial investigating atorvastatin as a treatment for sarcoidosis is under-way.[103][104] ACE inhibitors have been reported to cause remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and improvement in pulmonary sarcoidosis, including improvement in pulmonary function, remodeling of lung parenchyma and prevention of pulmonary fibrosis in separate case series'. [105] [106] [107] Nicotine patches have been found to possess anti-inflammatory effects in sarcoidosis patients, although whether they had disease-modifying effects requires further investigation.[108] Antimycobacterial treatment (drugs that kill off mycobacteria, the causative agents behind tuberculosis and leprosy) has also proven itself effective in treating chronic cutaneous (that is, it affects the skin) sarcoidosis in one clinical trial.[109] Quercetin has also been tried as a treatment for pulmonary sarcoidosis with some early success in one small trial.[110]

Because of its uncommon nature, the treatment of male reproductive tract sarcoidosis is controversial. Since the differential diagnosis includes testicular cancer, some recommend orchiectomy, even if evidence of sarcoidosis in other organs is present. In the newer approach, testicular, epididymal biopsy and resection of the largest lesion has been proposed.[51]

Prognosis

The disease can remit spontaneously or become chronic, with exacerbations and remissions. In some persons, it can progress to pulmonary fibrosis and death. About half of cases resolve without treatment or can be cured within 12–36 months, and most within five years. Some cases, however, may persist several decades.[9] Two-thirds of people with the condition achieve a remission within 10 years of the diagnosis.[111] When the heart is involved, the prognosis is generally less favourable, although, corticosteroids appear effective in improving AV conduction.[112][113] The prognosis tends to be less favourable in African Americans, compared to white Americans.[6] Persons with sarcoidosis appear to be at significantly increased risk for cancer, in particular lung cancer, lymphomas,[114] and cancer in other organs known to be affected in sarcoidosis.[115][116] In sarcoidosis-lymphoma syndrome, sarcoidosis is followed by the development of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[117] This may be attributed to the underlying immunological abnormalities that occur during the sarcoidosis disease process.[118] Sarcoidosis can also follow cancer[119] or occur concurrently with cancer.[120][121] There have been reports of hairy cell leukemia,[122] acute myeloid leukemia,[123] and acute myeloblastic leukemia[124] associated with sarcoidosis.

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis most commonly affects young adults of both sexes, although studies have reported more cases in females. Incidence is highest for individuals younger than 40 and peaks in the age-group from 20 to 29 years; a second peak is observed for women over 50.[9][112]

Sarcoidosis occurs throughout the world in all races with an average incidence of 16.5 per 100,000 in men and 19 per 100,000 in women. The disease is most common in Northern European countries and the highest annual incidence of 60 per 100,000 is found in Sweden and Iceland. In the United Kingdom the prevalence is 16 in 100,000.[125] In the United States, sarcoidosis is more common in people of African descent than Caucasians, with annual incidence reported as 35.5 and 10.9 per 100,000, respectively.[126] Sarcoidosis is less commonly reported in South America, Spain, India, Canada, and the Philippines. There may be a higher susceptibility to sarcoidosis in those with celiac disease. An association between the two disorders has been suggested.[127]

There also has been a seasonal clustering observed in sarcoidosis-affected individuals.[128] In Greece about 70% of diagnoses occur between March and May every year, in Spain about 50% of diagnoses occur between April and June, and in Japan it is mostly diagnosed during June and July.[128]

The differing incidence across the world may be at least partially attributable to the lack of screening programs in certain regions of the world, and the overshadowing presence of other granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis, that may interfere with the diagnosis of sarcoidosis where they are prevalent.[112] There may also be differences in the severity of the disease between people of different ethnicities. Several studies suggest the presentation in people of African origin may be more severe and disseminated than for Caucasians, who are more likely to have asymptomatic disease.[53] Manifestation appears to be slightly different according to race and sex. Erythema nodosum is far more common in men than in women and in Caucasians than in other races. In Japanese persons, ophthalmologic and cardiac involvement are more common than in other races.[9]

It is more common in certain occupations, namely firefighters, educators, military personnel, persons who work in industries where pesticides are used, law enforcement, and healthcare personnel.[129] In the year after the September 11 attacks, the rate of sarcoidosis incidence went up four-fold (to 86 cases per 100,000).[22][129]

History

It was first described in 1877 by Dr. Jonathan Hutchinson, a dermatologist as a condition causing red, raised rashes on the face, arms, and hands.[12] In 1888 the term Lupus pernio was coined by Dr. Ernest Besnier, another dermatologist.[130] Later in 1892 lupus pernio's histology was defined.[130] In 1902 bone involvement was first described by a group of three doctors.[130] Between 1909 and 1910 uveitis in sarcoidosis was first described, and later in 1915 it was emphasised, by Dr. Schaumann, that it was a systemic condition.[130] This same year lung involvement was also described.[130] In 1937 uveoparotid fever was first described and likewise in 1941 Löfgren syndrome was first described.[130] In 1958 the first international conference on sarcoidosis was called in London, likewise the first USA sarcoidosis conference occurred in Washington, DC in the year 1961.[130] It has also been called Besnier-Boeck disease or Besnier-Boeck-Schaumann disease.[131]

Society and culture

The World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) is an organisation of physicians involved in the diagnosis and treatment of sarcoidosis and related conditions.[132] WASOG publishes the journal Sarcoidosis, Vasculitis, and Diffuse Lung Diseases. Additionally, the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research (FSR) is devoted to supporting research into sarcoidosis and its possible treatments.[133]

There have been concerns that World Trade Center rescue workers are at a heightened risk for sarcoidosis.[134][135]

Comedian & actor Bernie Mac suffered from sarcoidosis. In 2005, he mentioned that the disease was in remission. [136] His death on August 9, 2008 was caused by complications from pneumonia, which was precipitated by pulmonary scarring attributed to his sarcoidosis.

Actress Karen Duffy suffers from sarcoidosis, specifically neurosarcoidosis. In the year 2000 she wrote a book that heavily deals with how it affected her life: Model Patient: My Life as an Incurable Wise-Ass.

In 2014, in a letter to the British medical journal The Lancet, it was suggested that the French Revolution leader Maximilien Robespierre suffered from sarcoidosis, and suggested that the condition caused him a notable impairment during his time as the head of the Reign of Terror.[137]

Etymology

The word "sarcoidosis" comes from Greek [σάρκο-] sarcο- meaning "flesh", the suffix -(e)ido (from the Greek εἶδος -eidos [usually omitting the initial e in English as the diphthong epsilon-iota in Classic Greek stands for a long "i" = English ee]) meaning "type", " resembles" or "like", and -sis, a common suffix in Greek meaning "condition". Thus the whole word means "a condition that resembles crude flesh". The first cases of sarcoïdosis, which were recognised as a new pathological entity, in Scandinavia, at the end of the 19th century exhibited skin nodules resembling cutaneous sarcomas, hence the name initially given.

Pregnancy

Sarcoidosis generally does not prevent successful pregnancy and delivery; the increase in estrogen levels during pregnancy may even have a slightly beneficial immunomodulatory effect. In most cases, the course of the disease is unaffected by pregnancy, with improvement in a few cases and worsening of symptoms in very few cases, although it is worth noting that a number of the immunosuppressants (such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine) used in corticosteroid-refractory sarcoidosis are known teratogens.[138]

References

- ^ a b c d e King, TE, Jr. (March 2008). "Sarcoidosis: Interstitial Lung Diseases: Merck Manual Home Edition". The Merck Manual Home Edition. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i "What Is Sarcoidosis?". NHLBI. June 14, 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Baughman RP, Culver DA, Judson MA; Culver; Judson (March 2011). "A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 183 (5): 573–81. doi:10.1164/rccm.201006-0865CI. PMC 3081278. PMID 21037016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "What Causes Sarcoidosis?". NHLBI. June 14, 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "Who Is at Risk for Sarcoidosis?". NHLBI. June 14, 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kamangar, N; Rohani, P; Shorr, AF (6 February 2014). Peters, SP; Talavera, F; Rice, TD; Mosenifar, Z (ed.). "Sarcoidosis". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Fauci, A.; Kasper, D.; Hauser, S.; Jameson, J.; Loscalzo, J. (2011). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07174889-6.

- ^ a b c d e Kamangar, N; Rohani, P; Shorr, AF (6 February 2014). Peters, SP; Talavera, F; Rice, TD; Mosenifar, Z (ed.). "Sarcoidosis Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, Valeyre D; Bouvry; Soler; Valeyre (2007). "Sarcoidosis". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2: 46. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-46. PMC 2169207. PMID 18021432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d King CS, Kelly W; Kelly (November 2009). "Treatment of sarcoidosis". Disease-a-month. 55 (11): 704–18. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2009.06.002. PMID 19857644.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet (London, England). 386 (9995): 743–800. PMID 26063472.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b James DG, Sharma OP; Sharma (September 2002). "From Hutchinson to now: a historical glimpse" (PDF). Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 8 (5): 416–23. doi:10.1097/01.MCP.0000020256.35153.12. PMID 12172446.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lung Diseases: Sarcoidosis: Signs & Symptoms". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Kamangar, N; Rohani, P; Shorr, AF (6 February 2014). Peters, SP; Talavera, F; Rice, TD; Mosenifar, Z (ed.). "Sarcoidosis Clinical Presentation". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sweiss NJ, Patterson K, Sawaqed R, Jabbar U, Korsten P, Hogarth K, Wollman R, Garcia JG, Niewold TB, Baughman RP; Patterson; Sawaqed; Jabbar; Korsten; Hogarth; Wollman; Garcia; Niewold; Baughman (August 2010). "Rheumatologic manifestations of sarcoidosis". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 31 (4): 463–73. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1262214. PMC 3314339. PMID 20665396.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Holmes J, Lazarus A; Lazarus (November 2009). "Sarcoidosis: extrathoracic manifestations". Disease-a-month. 55 (11): 675–92. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2009.05.002. PMID 19857642.

- ^ a b Dempsey OJ, Paterson EW, Kerr KM, Denison AR; Paterson; Kerr; Denison (28 August 2009). "Sarcoidosis". BMJ. 339: b3206. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3206. PMID 19717499.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tolaney SM, Colson YL, Gill RR (October 2007). "Sarcoidosis mimicking metastatic breast cancer". Clin. Breast Cancer. 7 (10): 804–10. doi:10.3816/CBC.2007.n.044. PMID 18021484.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baughman RP, Lower EE, Gibson K; Lower; Gibson (June 2012). "Pulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis". Presse medicale. 41 (6 Pt 2): e289–302. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.03.019. PMID 22579234.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fuhrer G, Myers JN; Myers (November 2009). "Intrathoracic sarcoidosis". Disease-a-month. 55 (11): 661–74. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2009.04.009. PMID 19857641.

- ^ Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Freynet O, Humbert M, Brillet PY, Kambouchner M, Valeyre D; Uzunhan; Freynet; Humbert; Brillet; Kambouchner; Valeyre (June 2012). "Pulmonary hypertension complicating sarcoidosis". Presse medicale. 41 (6 Pt 2): e303–16. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.04.003. PMID 22608948.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Chen ES, Moller DR; Moller (12 July 2011). "Sarcoidosis—scientific progress and clinical challenges". Nature reviews. Rheumatology. 7 (8): 457–67. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2011.93. PMID 21750528.

- ^ Wasfi YS, Fontenot AP. "Chapter 12. Sarcoidosis." In: Hanley ME, Welsh CH, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment in Pulmonary Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

- ^ a b Mañá J, Marcoval J; Marcoval (June 2012). "Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis". Presse medicale. 41 (6 Pt 2): e355–74. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.02.046. PMID 22579238.

- ^ Heath CR, David J, Taylor SC; David; Taylor (January 2012). "Sarcoidosis: Are there differences in your skin of color patients?". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 66 (1): 121.e1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.068. PMID 22000704.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lodha S, Sanchez M, Prystowsky S; Sanchez; Prystowsky (August 2009). "Sarcoidosis of the skin: a review for the pulmonologist" (PDF). Chest. 136 (2): 583–96. doi:10.1378/chest.08-1527. PMID 19666758.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b James, WD; Berger, T; Dirk, M (2006). Andrew's diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 708–711. ISBN 978-0808923510.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ House NS, Welsh JP, English JC; Welsh; English Jc (15 August 2012). "Sarcoidosis-induced alopecia". Dermatology Online Journal. 18 (8): 4. PMID 22948054.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Doughan AR, Williams BR; Williams (2006). "Cardiac sarcoidosis". Heart. 92 (2): 282–8. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.080481. PMC 1860791. PMID 16415205.

- ^ a b Youssef G, Beanlands RS, Birnie DH, Nery PB; Beanlands; Birnie; Nery (December 2011). "Cardiac sarcoidosis: applications of imaging in diagnosis and directing treatment". Heart. 97 (24): 2078–87. doi:10.1136/hrt.2011.226076. PMID 22116891.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reuhl J, Schneider M, Sievert H, Lutz FU, Zieger G; Schneider; Sievert; Lutz; Zieger (October 1997). "Myocardial sarcoidosis as a rare cause of sudden cardiac death". Forensic Sci. Int. 89 (3): 145–53. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(97)00106-0. PMID 9363623.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rajasenan V, Cooper ES; Cooper (1969). "Myocardial sarcoidosis, bouts of ventricular tachycardia, psychiatric manifestations and sudden death. A case report". J Natl Med Assoc. 61 (4): 306–9. PMC 2611747. PMID 5796402.

- ^ Chapelon-Abric C (2012). "Cardiac sarcoidosis". Presse Med. 41 (6 Pt 2): e317–30. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.04.002. PMID 22608949.

- ^ Bodaghi B, Touitou V, Fardeau C, Chapelon C, LeHoang P; Touitou; Fardeau; Chapelon; Lehoang (June 2012). "Ocular sarcoidosis". Presse medicale. 41 (6 Pt 2): e349–54. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.04.004. PMID 22595776.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Papadia M, Herbort CP, Mochizuki M; Herbort; Mochizuki (December 2010). "Diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis". Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 18 (6): 432–41. doi:10.3109/09273948.2010.524344. PMID 21091056.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Qazi FA, Thorne JE, Jabs DA; Thorne; Jabs (October 2003). "Scleral nodule associated with sarcoidosis". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 136 (4): 752–4. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00454-9. PMID 14516826.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Nozaki K, Judson MA; Judson (June 2012). "Neurosarcoidosis: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment". Presse medicale. 41 (6 Pt 2): e331–48. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2011.12.017. PMID 22595777.

- ^ Said G, Lacroix C, Plante-Bordeneuve V; Lacroix; Planté-Bordeneuve; Le Page; Pico; Presles; Senant; Remy; Rondepierre; Mallecourt (2002). "Nerve granulomas and vasculitis in sarcoid peripheral neuropathy". Brain. 125 (Pt 2): 264–75. doi:10.1093/brain/awf027. PMID 11844727.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Vardhanabhuti V, Venkatanarasimha N, Bhatnagar G, Maviki M, Iyengar S, Adams WM, Suresh P; Venkatanarasimha; Bhatnagar; Maviki; Iyengar; Adams; Suresh (March 2012). "Extra-pulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis" (PDF). Clinical Radiology. 67 (3): 263–76. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2011.04.018. PMID 22094184.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tavee J, Culver D; Culver (2011). "Sarcoidosis and small-fiber neuropathy". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 15 (3): 201–6. doi:10.1007/s11916-011-0180-8. PMID 21298560.

- ^ Heij L, Dahan A, Hoitsma E; Dahan; Hoitsma (2012). "Sarcoidosis and Pain Caused by Small-Fiber Neuropathy". Pain Research and Treatment. 2012: 256024. doi:10.1155/2012/256024. PMC 3523152. PMID 23304492.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Porter N, Beynon HL, Randeva HS; Beynon; Randeva (2003). "Endocrine and reproductive manifestations of sarcoidosis". QJM. 96 (8): 553–61. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg103. PMID 12897340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barbour GL, Coburn JW, Slatopolsky E, Norman AW, Horst RL; Coburn; Slatopolsky; Norman; Horst (August 1981). "Hypercalcemia in an anephric patient with sarcoidosis: evidence for extrarenal generation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D". N. Engl. J. Med. 305 (8): 440–3. doi:10.1056/NEJM198108203050807. PMID 6894783.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rheumatology Diagnosis & Therapies" (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 342.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Antonelli A, Fazzi P, Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Ferrannini E; Fazzi; Fallahi; Ferrari; Ferrannini (August 2006). "Prevalence of hypothyroidism and Graves disease in sarcoidosis". Chest. 130 (2): 526–32. doi:10.1378/chest.130.2.526. PMID 16899854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manchanda A, Patel S, Jiang JJ, Babu AR; Patel; Jiang; Babu (March–April 2013). "Thyroid: an unusual hideout for sarcoidosis" (PDF). Endocrine practice. 19 (2): e40–3. doi:10.4158/EP12131.CR. PMID 23337134.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Fausto N, Abbas A (2004). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of disease (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 737–9. ISBN 978-0721601878.

- ^ Tokala, Hemasri; Polsani, Karthik; Kalavakunta, Jagadeesh K. (2013-01-01). "Gastric sarcoidosis: a rare clinical presentation". Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. 2013: 260704. doi:10.1155/2013/260704. ISSN 2090-6528. PMC 3867894. PMID 24368949.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Vera C, Funaro D, Bouffard D; Funaro; Bouffard (July–August 2013). "Vulvar sarcoidosis: case report and review of the literature". Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 17 (4): 287–90. PMID 23815963.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Paknejad O, Gilani MA, Khoshchehreh M; Gilani; Khoshchehreh (April–June 2011). "Testicular masses in a man with a plausible sarcoidosis". Indian J Urol. 27 (2): 269–27. doi:10.4103/0970-1591.82848. PMC 3142840. PMID 21814320.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Paknejad O, Gilani MA, Khoshchehreh M; Gilani; Khoshchehreh (April–June 2011). "Testicular masses in a man with a plausible sarcoidosis". Indian Journal of Urology. 27 (2): 269–27. doi:10.4103/0970-1591.82848. PMC 3142840. PMID 21814320.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cremers JP, Drent M, Baughman RP, Wijnen PA, Koek GH; Drent; Baughman; Wijnen; Koek (September 2012). "Therapeutic approach of hepatic sarcoidosis". Curr Opin Pulm Med. 18 (5): 472–82. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283541626. PMID 22617809.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Statement on Sarcoidosis" (PDF). American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 160 (2): 736–755. August 1999. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99. PMID 10430755.

- ^ Wurm K, Löhr G; Löhr (1986). "Immuno-cytological blood tests in cases of sarcoidosis". Sarcoidosis. 3 (1): 52–9. PMID 3033787.

- ^ Chen HC, Kang BH, Lai CT, Lin YS; Kang; Lai; Lin (July 2005). "Sarcoidal granuloma in cervical lymph nodes". Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 68 (7): 339–42. doi:10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70172-8. PMID 16038376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rao, DA; Dellaripa, PF (May 2013). "Extrapulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis". Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 39 (2): 277–97. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2013.02.007. PMID 23597964.

- ^ Shimamura, Y; Taniguchi, Y; Yoshimatsu, R; Kawase, S; Yamagami, T; Terada, Y (28 August 2015). "Granulomatous periostitis and tracheal involvement in sarcoidosis". Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 55: 102. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kev319. PMID 26320137.

- ^ Korkmaz, C; Efe, B; Tel, N; Kabukçuoglu, S; Erenoglu, E (March 1999). "Sarcoidosis with palpable nodular myositis, periostitis and large-vessel vasculitis stimulating Takayasu's arteritis". Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 38 (3): 287–8. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/38.3.287. PMID 10325674.

- ^ Rossman MD, Kreider ME; Kreider (August 2007). "Lesson learned from ACCESS (A Case Controlled Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis)". Proc Am Thorac Soc. 4 (5): 453–6. doi:10.1513/pats.200607-138MS. PMID 17684288.

- ^ Cathcart S, Sami N, Elewski B; Sami; Elewski (May 2012). "Sarcoidosis as an adverse effect of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 11 (5): 609–12. PMID 22527429.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iannuzzi MC (August 2007). "Advances in the genetics of sarcoidosis". Proc Am Thorac Soc. 4 (5): 457–60. doi:10.1513/pats.200606-136MS. PMID 17684289.

- ^ Spagnolo P, Grunewald J; Grunewald (May 2013). "Recent advances in the genetics of sarcoidosis". Journal of Medical Genetics. 50 (5): 290–7. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101532. PMID 23526832.

- ^ Grunewald J, Eklund A, Olerup O; Eklund; Olerup (March 2004). "Human leukocyte antigen class I alleles and the disease course in sarcoidosis patients". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169 (6): 696–702. doi:10.1164/rccm.200303-459OC. PMID 14656748.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grunewald, J (August 2010). "Review: role of genetics in susceptibility and outcome of sarcoidosis". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 31 (4): 380–9. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1262206. PMID 20665388.

- ^ Gialafos, Elias; Triposkiadis, Filippos; Kouranos, Vassilios; Rapti, Aggeliki; Kosmas, Ilias; Manali, Efrosini; Giamouzis, Grigorios; Elezoglou, Antonia; Peros, Ilias (2014-12-01). "Relationship between tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFA) gene polymorphisms and cardiac sarcoidosis". In Vivo (Athens, Greece). 28 (6): 1125–1129. ISSN 1791-7549. PMID 25398810.

- ^ Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Eckstein C; Sotirchos; Eckstein (March 2012). "Etiology of sarcoidosis: does infection play a role?". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 85 (1): 133–41. PMC 3313528. PMID 22461752.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Müller-Quernheim J, Prasse A, Zissel G; Prasse; Zissel (June 2012). "Pathogenesis of sarcoidosis". Presse medicale. 41 (6 Pt 2): e275–87. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.03.018. PMID 22595775.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Jindal SK; Agarwal; Aggarwal; Jindal (September 2007). "Molecular evidence for the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis: a meta-analysis". Eur. Respir. J. 30 (3): 508–16. doi:10.1183/09031936.00002607. PMID 17537780.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Almenoff PL, Johnson A, Lesser M, Mattman LH; Johnson; Lesser; Mattman (May 1996). "Growth of acid fast L forms from the blood of patients with sarcoidosis". Thorax. 51 (5): 530–3. doi:10.1136/thx.51.5.530. PMC 473601. PMID 8711683.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morgenthau AS, Iannuzzi MC; Iannuzzi (January 2011). "Recent advances in sarcoidosis" (PDF). Chest. 139 (1): 174–82. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0188. PMID 21208877.

- ^ Padilla ML, Schilero GJ, Teirstein AS; Schilero; Teirstein (March 2002). "Donor-acquired sarcoidosis". Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 19 (1): 18–24. PMID 12002380.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Romagnani S (June 1997). "The Th1/Th2 paradigm". Immunol. Today. 18 (6): 263–6. doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(97)80019-9. PMID 9190109.

- ^ Morell F, Levy G, Orriols R, Ferrer J, De Gracia J, Sampol G; Levy; Orriols; Ferrer; De Gracia; Sampol (April 2002). "Delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity tests and lymphopenia as activity markers in sarcoidosis". Chest. 121 (4): 1239–44. doi:10.1378/chest.121.4.1239. PMID 11948059.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Bargagli E, Olivieri C, Rottoli P; Olivieri; Rottoli (December 2011). "Cytokine modulators in the treatment of sarcoidosis". Rheumatology International. 31 (12): 1539–44. doi:10.1007/s00296-011-1969-9. PMID 21644041.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kettritz R, Goebel U, Fiebeler A, Schneider W, Luft F; Goebel; Fiebeler; Schneider; Luft (October 2006). "The protean face of sarcoidosis revisited" (PDF). Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 21 (10): 2690–4. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfl369. PMID 16861724.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Verschueren K, Van Essche E, Verschueren P, Taelman V, Westhovens R; Van Essche; Verschueren; Taelman; Westhovens (November 2007). "Development of sarcoidosis in etanercept-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients". Clin. Rheumatol. 26 (11): 1969–71. doi:10.1007/s10067-007-0594-1. PMID 17340045.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parrish S, Turner JF; Turner (November 2009). "Diagnosis of sarcoidosis". Disease-a-month. 55 (11): 693–703. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2009.06.001. PMID 19857643.

- ^ Hawtin KE, Roddie ME, Mauri FA, Copley SJ; Roddie; Mauri; Copley (August 2010). "Pulmonary sarcoidosis: the 'Great Pretender'". Clinical Radiology. 65 (8): 642–50. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2010.03.004. PMID 20599067.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baughman RP, Culver DA, Judson MA; Culver; Judson (1 March 2011). "A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 183 (5): 573–81. doi:10.1164/rccm.201006-0865CI. PMC 3081278. PMID 21037016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miliauskas S, Zemaitis M, Sakalauskas R; Zemaitis; Sakalauskas (2010). "Sarcoidosis—moving to the new standard of diagnosis?" (PDF). Medicina. 46 (7): 443–6. PMID 20966615.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Kamangar, N; Rohani, P; Shorr, AF (6 February 2014). Peters, SP; Talavera, F; Rice, TD; Mosenifar, Z (ed.). "Sarcoidosis Workup". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Allmendinger A, Perone R (2009). "Case of the Month". Diagnostic Imaging. 31 (9): 10.

- ^ Joanne Mambretti (2004). "Chest X-ray Stages of Sarcoidosis" (PDF). Journal of Insurance Medicine: 91–92. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ Andonopoulos AP, Papadimitriou C, Melachrinou M (2001). "Asymptomatic gastrocnemius muscle biopsy: an extremely sensitive and specific test in the pathologic confirmation of sarcoidosis presenting with hilar adenopathy" (PDF). Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 19 (5): 569–72. PMID 11579718.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ White, ES; Lynch Jp, 3rd (June 2007). "Current and emerging strategies for the management of sarcoidosis". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (9): 1293–1311. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.9.1293. PMID 17563264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Paramothayan NS, Lasserson TJ, Jones PW; Lasserson; Jones (18 April 2005). "Corticosteroids for pulmonary sarcoidosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001114. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001114.pub2. PMID 15846612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sahoo DH, Bandyopadhyay D, Xu M, Pearson K, Parambil JG, Lazar CA, Chapman JT, Culver DA; Bandyopadhyay; Xu; Pearson; Parambil; Lazar; Chapman; Culver (November 2011). "Effectiveness and safety of leflunomide for pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis" (PDF). The European Respiratory Journal. 38 (5): 1145–50. doi:10.1183/09031936.00195010. PMID 21565914.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Panselinas E, Judson MA; Judson (October 2012). "Acute pulmonary exacerbations of sarcoidosis" (PDF). Chest. 142 (4): 827–36. doi:10.1378/chest.12-1060. PMID 23032450.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Baughman RP, Nunes H, Sweiss NJ, Lower EE; Nunes; Sweiss; Lower (June 2013). "Established and experimental medical therapy of pulmonary sarcoidosis". The European Respiratory Journal. 41 (6): 1424–38. doi:10.1183/09031936.00060612. PMID 23397302.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bhat P, Cervantes-Castañeda RA, Doctor PP, Anzaar F, Foster CS; Cervantes-Castañeda; Doctor; Anzaar; Foster (May–June 2009). "Mycophenolate mofetil therapy for sarcoidosis-associated uveitis". Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 17 (3): 185–90. doi:10.1080/09273940902862992. PMID 19585361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Androdias G, Maillet D, Marignier R, Pinède L, Confavreux C, Broussolle C, Vukusic S, Sève P; Maillet; Marignier; Pinède; Confavreux; Broussolle; Vukusic; Sève (29 May 2011). "Mycophenolate mofetil may be effective in CNS sarcoidosis but not in sarcoid myopathy". Neurology. 76 (13): 1168–72. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318212aafb. PMID 21444902.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Judson, MA (October 2012). "The treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis". Respiratory Medicine. 106 (10): 1351–1361. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.013. PMID 22495110.

- ^ Brill AK, Ott SR, Geiser T; Ott; Geiser (2013). "Effect and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis: a retrospective study". Respiration. 86 (5): 376–83. doi:10.1159/000345596. PMID 23295253.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tikoo RK, Kupersmith MJ, Finlay JL; Kupersmith; Finlay (22 April 2004). "Treatment of Refractory Neurosarcoidosis with Cladribine" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (17): 1798–1799. doi:10.1056/NEJMc032345. PMID 15103013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maneiro JR, Salgado E, Gomez-Reino JJ, Carmona L; Salgado; Gomez-Reino; Carmona; Biobadaser Study (August 2012). "Efficacy and safety of TNF antagonists in sarcoidosis: data from the Spanish registry of biologics BIOBADASER and a systematic review". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 42 (1): 89–103. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.12.006. PMID 22387045.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Antoniu, SA (January 2010). "Targeting the TNF-alpha pathway in sarcoidosis". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 14 (1): 21–9. doi:10.1517/14728220903449244. PMID 20001207.

- ^ a b c Beegle SH, Barba K, Gobunsuy R, Judson MA; Barba; Gobunsuy; Judson (2013). "Current and emerging pharmacological treatments for sarcoidosis: a review". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 7: 325–38. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S31064. PMC 3627473. PMID 23596348.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Callejas-Rubio JL, López-Pérez L, Ortego-Centeno N; López-Pérez; Ortego-Centeno (December 2008). "Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor treatment for sarcoidosis". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 4 (6): 1305–13. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S967. PMC 2643111. PMID 19337437.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Dastoori M, Fedele S, Leao JC, Porter SR; Fedele; Leao; Porter (April 2013). "Sarcoidosis — a clinically orientated review". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 42 (4): 281–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01198.x. PMID 22845844.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bakker GJ, Haan YC, Maillette de Buy Wenniger LJ, Beuers U; Haan; Maillette de Buy Wenniger LJ; Beuers (October 2012). "Sarcoidosis of the liver: to treat or not to treat?" (PDF). The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 70 (8): 349–56. PMID 23065982.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baughman RP, Judson MA, Ingledue R, Craft NL, Lower EE; Judson; Ingledue; Craft; Lower (February 2012). "Efficacy and safety of apremilast in chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis" (PDF). Archives of Dermatology. 148 (2): 262–4. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.301. PMID 22004880.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clinical trial number NCT01830959 for "Use of Roflumilast to Prevent Exacerbations in Fibrotic Sarcoidosis Patients (REFS)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Belkhou A, Younsi R, El Bouchti I, El Hassani S; Younsi; El Bouchti; El Hassani (July 2008). "Rituximab as a treatment alternative in sarcoidosis". Joint, Bone, Spine. 75 (4): 511–2. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.01.025. PMID 18562234.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clinical trial number NCT00279708 for "Atorvastatin to Treat Pulmonary Sarcoidosis" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Kaura V., Kaura NV., Kaura BN., Kaura. "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in the treatment of sarcoidosis and association with ACE gene polymorphism: case series."". Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 55 (2): 105–7. PMID 24047001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaura Vinod, Kaura Samantha H., Kaura Claire S. (2007). "ACE Inhibitor in the Treatment of Cutaneous and Lymphatic Sarcoidosis". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 8 (3): 183–186. doi:10.2165/00128071-200708030-00006.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rosenbloom J, Castro SV, Jimenez S (2010). "Fibrotic diseases: cellular and molecular mechanisms and novel therapies". Ann Intern Med. 152: 159–66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-3-201002020-00007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Julian MW, Shao G, Schlesinger LS, Huang Q, Cosmar DG, Bhatt NY, Culver DA, Baughman RP, Wood KL, Crouser ED; Shao; Schlesinger; Huang; Cosmar; Bhatt; Culver; Baughman; Wood; Crouser (1 February 2013). "Nicotine treatment improves Toll-like receptor 2 and Toll-like receptor 9 responsiveness in active pulmonary sarcoidosis" (PDF). Chest. 143 (2): 461–70. doi:10.1378/chest.12-0383. PMID 22878868.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Drake WP, Oswald-Richter K, Richmond BW, Isom J, Burke VE, Algood H, Braun N, Taylor T, Pandit KV, Aboud C, Yu C, Kaminski N, Boyd AS, King LE; Oswald-Richter; Richmond; Isom; Burke; Algood; Braun; Taylor; Pandit; Aboud; Yu; Kaminski; Boyd; King (September 2013). "Oral antimycobacterial therapy in chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis: a randomized, single-masked, placebo-controlled study". JAMA Dermatology. 149 (9): 1040–9. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4646. PMC 3927541. PMID 23863960.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boots AW, Drent M, de Boer VC, Bast A, Haenen GR; Drent; De Boer; Bast; Haenen (August 2011). "Quercetin reduces markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in sarcoidosis". Clinical Nutrition. 30 (4): 506–12. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2011.01.010. PMID 21324570.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "What Is Sarcoidosis?". National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. National Institutes of Health. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Syed J, Myers R; Myers (January 2004). "Sarcoid heart disease". Can J Cardiol. 20 (1): 89–93. PMID 14968147.

- ^ Sadek MM, Yung D, Birnie DH, Beanlands RS, Nery PB; Yung; Birnie; Beanlands; Nery (September 2013). "Corticosteroid therapy for cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review". Can J Cardiol. 29 (9): 1034–41. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.02.004. PMID 23623644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karakantza M, Matutes E, MacLennan K, O'Connor NT, Srivastava PC, Catovsky D; Matutes; MacLennan; O'Connor; Srivastava; Catovsky (1996). "Association between sarcoidosis and lymphoma revisited". J. Clin. Pathol. 49 (3): 208–12. doi:10.1136/jcp.49.3.208. PMC 500399. PMID 8675730.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, Hillerdal G, Ekbom A; Grunewald; Eklund; Hillerdal; Ekbom (November 1999). "Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 160 (5 Pt 1): 1668–72. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9904045. PMID 10556138.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tana C, Giamberardino MA, Di Gioacchino M, Mezzetti A, Schiavone C; Giamberardino; Di Gioacchino; Mezzetti; Schiavone (April–June 2013). "Immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis and risk of malignancy: a lost truth?". International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 26 (2): 305–13. PMID 23755746.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kornacker M, Kraemer A, Leo E, Ho AD; Kraemer; Leo; Ho (2002). "Occurrence of sarcoidosis subsequent to chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: report of two cases". Ann. Hematol. 81 (2): 103–5. doi:10.1007/s00277-001-0415-6. PMID 11907791.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Suvajdzic N, Milenkovic B, Perunicic M, Stojsic J, Jankovic S; Milenkovic; Perunicic; Stojsic; Jankovic (2007). "Two cases of sarcoidosis-lymphoma syndrome". Med. Oncol. 24 (4): 469–71. doi:10.1007/s12032-007-0026-8. PMID 17917102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yao M, Funk GF, Goldstein DP, DeYoung BR, Graham MM; Funk; Goldstein; Deyoung; Graham (2005). "Benign lesions in cancer patients: Case 1. Sarcoidosis after chemoradiation for head and neck cancer". J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (3): 640–1. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.089. PMID 15659510.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yamasawa H, Ishii Y, Kitamura S; Ishii; Kitamura (2000). "Concurrence of sarcoidosis and lung cancer. A report of four cases". Respiration. 67 (1): 90–3. doi:10.1159/000029470. PMID 10705270.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zambrana F, Antúnez A, García-Mata J, Mellado JM, Villar JL; Antúnez; García-Mata; Mellado; Villar (2009). "Sarcoidosis as a diagnostic pitfall of pancreatic cancer". Clin Transl Oncol. 11 (6): 396–8. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0375-1. PMID 19531456.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schiller G, Said J, Pal S; Said; Pal (2003). "Hairy cell leukemia and sarcoidosis: a case report and review of the literature". Leukemia. 17 (10): 2057–9. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403074. PMID 14513061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maloisel F, Oberling F; Oberling (1992). "Acute myeloid leukemia complicating sarcoidosis". J R Soc Med. 85 (1): 58–9. PMC 1293471. PMID 1548666.

- ^ Reich JM (1985). "Acute myeloblastic leukemia and sarcoidosis. Implications for pathogenesis". Cancer. 55 (2): 366–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19850115)55:2<366::AID-CNCR2820550212>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 3855267.

- ^ Sam, Amir H.; James T.H. Teo (2010). Rapid Medicine. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1405183233.

- ^ Henke CE, Henke G, Elveback LR, Beard CM, Ballard DJ, Kurland LT; Henke; Elveback; Beard; Ballard; Kurland (1986). "The epidemiology of sarcoidosis in Rochester, Minnesota: a population-based study of incidence and survival" (PDF). Am. J. Epidemiol. 123 (5): 840–5. PMID 3962966.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rutherford RM, Brutsche MH, Kearns M, Bourke M, Stevens F, Gilmartin JJ; Brutsche; Kearns; Bourke; Stevens; Gilmartin (September 2004). "Prevalence of coeliac disease in patients with sarcoidosis". Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16 (9): 911–5. doi:10.1097/00042737-200409000-00016. PMID 15316417.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Baughman RP, Lower EE, du Bois RM; Lower; Du Bois (29 March 2003). "Sarcoidosis". Lancet. 361 (9363): 1111–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12888-7. PMID 12672326.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lazarus, A (November 2009). "Sarcoidosis: epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and genetics". Disease-a-month. 55 (11): 649–60. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2009.04.008. PMID 19857640.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sharma, OP (2005). "Chapter 1: Definition and history of sarcoidosis". Sarcoidosis. Sheffield: European Respiratory Society Journals. ISBN 9781904097884.

- ^ Babalian, L (26 January 1939). "Disease of Besnier-Boeck-Schaumann". New England Journal of Medicine. 220 (4): 143–145. doi:10.1056/NEJM193901262200404.

- ^ "Join WASOG". World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disease. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Mission & Goals". Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Izbicki G, Chavko R, Banauch GI, Weiden MD, Berger KI, Aldrich TK, Hall C, Kelly KJ, Prezant DJ; Chavko; Banauch; Weiden; Berger; Aldrich; Hall; Kelly; Prezant (May 2007). "World Trade Center "sarcoid-like" granulomatous pulmonary disease in New York City Fire Department rescue workers" (PDF). Chest. 131 (5): 1414–23. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2114. PMID 17400664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "9/11 Health - What We Know About the Health Effects of 9/11". NYC. US Government. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Grimes, William (10 Aug 2008). "Bernie Mac, Acerbic Stand-Up Comedian and Irascible TV Dad, Dies at 50". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Charlier P, Froesch P; Froesch (2013). "Robespierre: the oldest case of sarcoidosis?". Lancet. 382 (9910): 2068. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62694-X. PMID 24360387.

- ^ Subramanian P, Chinthalapalli H, Krishnan M; Chinthalapalli; Krishnan; Tarlo; Lobbedez; Pineda; Oreopoulos (September 2004). "Pregnancy and sarcoidosis: an insight into the pathogenesis of hypercalciuria". Chest. 126 (3): 995–8. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.995. PMID 15364785.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)