European Space Agency Science Programme: Difference between revisions

Yiosie2356 (talk | contribs) →Cosmic Vision: Reworded info regarding L-class missions under Cosmic Vision |

Yiosie2356 (talk | contribs) Rewording and added a ref for Horizon 2000 timeframe |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

=== Horizon 2000 === |

=== Horizon 2000 === |

||

''Horizon 2000'' was the first programme focused on science missions |

''Horizon 2000'' was the first programme focused on science missions. It was drafted by the European Space Agency in 1984, which wanted a dedicated focus on funding and developing new science missions while also maintaining contemporary ones.<ref name="horizon2000-desc">{{cite journal|last1=Bonnet|first1=R. M.|title=ESA's 'Horizon 2000' Programme|journal=Esa Special Publication|volume=310|date=August 1990|pages=167–173|bibcode=1990ESASP.310..167B}}</ref> The program, while providing funding for already-launched missions and those in late development such as the ''[[International Ultraviolet Explorer]]'', ''[[Hipparcos]]'' and ''[[Ulysses (spacecraft)|Ulysses]]'', supported a series of brand new missions, divided into large-budget ventures known as "cornerstone" missions, and medium-sized missions known colloquially as "blue missions".<ref name="horizon2000-desc"/> The plan originally called for three cornerstone missions throughout the scope of the programme, spanning the 1985–2005 timeframe.<ref name="horizon2000-figure">{{cite book |author=Vincent Minier, etal. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RppADwAAQBAJ&pg=PA40 |title=Inventing a Space Mission: The Story of the Herschel Space Observatory |page=40 |work=[[International Space Science Institute]] |publisher=[[Springer Publishing]] |isbn=978-3-319-60023-9 |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-60024-9}}</ref> However, the Solar-Terrestrial Science Programme, which consisted of the ''[[Solar and Heliospheric Observatory]]'' (''SOHO'') and ''[[Cluster (spacecraft)|Cluster]]'' missions, was adopted into the Horizon 2000 plan, leading the two missions to become ''Cornerstone 1'' of what became four cornerstone missions.<ref name="cornerstone-1">{{cite book|author1=[[European Science Foundation]]|author2=[[National Research Council (United States)|National Research Council]]|title=U.S. – European Collaboration in Space Science|journal=U.s.-European Collaboration in Space Science Publisher: National Academy Press|date=1998|publisher=National Academies Press|location=[[Washington, D.C.]]|isbn=978-0-309-05984-8|page=52|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FLq_ddcuNPkC&pg=PA52|bibcode=1998usec.book.....N}}</ref> ''[[XMM-Newton]]'' was selected as the second cornerstone mission of the programme, while ''[[Rosetta (spacecraft)|Rosetta]]'' and ''FIRST'' were selected in November 1993 as the third and fourth cornerstone missions,<ref name="cornerstone-3and4">{{cite journal|title=ESA confirms ROSETTA and FIRST in its long-term science programme |url=http://www.esa.int/For_Media/Press_Releases/ESA_confirms_ROSETTA_and_FIRST_in_its_long-term_science_programme| journal=Xmm-Newton Press Release|pages=43| accessdate=21 December 2016| archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161221041645/http://www.esa.int/For_Media/Press_Releases/ESA_confirms_ROSETTA_and_FIRST_in_its_long-term_science_programme|archivedate=21 December 2016 |date=8 November 1993|bibcode=1993xmm..pres...43.}}</ref> with the latter mission eventually being rechristened the ''[[Herschel Space Observatory]]''. |

||

Part of the Horizon 2000 programme was also a class of medium-sized missions known as "blue missions" – their name deriving from the colour of the box that represents them in the original Horizon 2000 proposal diagram from 1984.<ref name="bluemissions">{{cite book|last1=Fletcher|first1=Karen|last2=Bonnet|first2=Roger-Maurice|title=Titan – from discovery to encounter: Proceedings of the International Conference; 13 – 17 April 2004, ESTEC, Noordwijk, the Netherlands|journal=Titan - from Discovery to Encounter|volume=1278|date=2004|publisher=[[European Space Agency|ESA Publications Division]]|location=[[Noordwijk]]|isbn=978-92-9092-997-0|page=201|bibcode=2004ESASP1278..201B}}</ref> The ''[[Huygens (spacecraft)|Huygens]]'' lander, a component of the ''[[Cassini–Huygens]]'' mission, became the first designated medium-sized mission of the Horizon 2000 programme, after its selection in November 1988.<ref name="bluemissions"/> ''[[INTEGRAL]]'' was chosen as the succeeding medium-sized mission in June 1993,<ref name="integral">{{cite web|title=INTEGRAL (INTErnational Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Lab) |url=http://ipl.uv.es/?q=content/project/integral-international-gamma-ray-astrophysics-lab |website=Image Processing Laboratory |publisher=[[University of Valencia]] |accessdate=21 December 2016 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161221071356/http://ipl.uv.es/?q=content%2Fproject%2Fintegral-international-gamma-ray-astrophysics-lab |archivedate=21 December 2016 |deadurl=yes |df= }}</ref> followed three years later by the selection of ''COBRAS/SAMBA'', later rechristened ''[[Planck (spacecraft)|Planck]]'', as the third medium-sized mission in July 1996.<ref name="cobras-samba">{{cite book|last1=Van Tran |first1=J. |title=Fundamental Parameters in Cosmology |date=1998 |publisher=Atlantica Séguier Frontières |location=[[Paris]] |isbn=978-2-86332-233-8|page=255 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5UYK0akglYUC&pg=PA255}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=History of Planck - COBRAS/SAMBA: The Beginning of Planck|url=http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/planck/cobras-name|website=ESA Cosmos Portal|publisher=[[European Space Agency]]|accessdate=25 December 2016|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161225061811/http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/planck/cobras-name|archivedate=25 December 2016|date=December 2013}}</ref> As of December 2016, four Horizon 2000 missions, including three cornerstone and one medium-sized mission, remain operational. |

Part of the Horizon 2000 programme was also a class of medium-sized missions known as "blue missions" – their name deriving from the colour of the box that represents them in the original Horizon 2000 proposal diagram from 1984.<ref name="bluemissions">{{cite book|last1=Fletcher|first1=Karen|last2=Bonnet|first2=Roger-Maurice|title=Titan – from discovery to encounter: Proceedings of the International Conference; 13 – 17 April 2004, ESTEC, Noordwijk, the Netherlands|journal=Titan - from Discovery to Encounter|volume=1278|date=2004|publisher=[[European Space Agency|ESA Publications Division]]|location=[[Noordwijk]]|isbn=978-92-9092-997-0|page=201|bibcode=2004ESASP1278..201B}}</ref> The ''[[Huygens (spacecraft)|Huygens]]'' lander, a component of the ''[[Cassini–Huygens]]'' mission, became the first designated medium-sized mission of the Horizon 2000 programme, after its selection in November 1988.<ref name="bluemissions"/> ''[[INTEGRAL]]'' was chosen as the succeeding medium-sized mission in June 1993,<ref name="integral">{{cite web|title=INTEGRAL (INTErnational Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Lab) |url=http://ipl.uv.es/?q=content/project/integral-international-gamma-ray-astrophysics-lab |website=Image Processing Laboratory |publisher=[[University of Valencia]] |accessdate=21 December 2016 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161221071356/http://ipl.uv.es/?q=content%2Fproject%2Fintegral-international-gamma-ray-astrophysics-lab |archivedate=21 December 2016 |deadurl=yes |df= }}</ref> followed three years later by the selection of ''COBRAS/SAMBA'', later rechristened ''[[Planck (spacecraft)|Planck]]'', as the third medium-sized mission in July 1996.<ref name="cobras-samba">{{cite book|last1=Van Tran |first1=J. |title=Fundamental Parameters in Cosmology |date=1998 |publisher=Atlantica Séguier Frontières |location=[[Paris]] |isbn=978-2-86332-233-8|page=255 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5UYK0akglYUC&pg=PA255}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=History of Planck - COBRAS/SAMBA: The Beginning of Planck|url=http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/planck/cobras-name|website=ESA Cosmos Portal|publisher=[[European Space Agency]]|accessdate=25 December 2016|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161225061811/http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/planck/cobras-name|archivedate=25 December 2016|date=December 2013}}</ref> As of December 2016, four Horizon 2000 missions, including three cornerstone and one medium-sized mission, remain operational. |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

=== Horizon 2000 Plus === |

=== Horizon 2000 Plus === |

||

[[File:GAIA (14050944939).jpg|thumb|The ''[[Gaia (spacecraft)|Gaia]]'' [[astrometry]] mission was launched as one of three missions in the Horizon 2000 Plus campaign.]] |

[[File:GAIA (14050944939).jpg|thumb|The ''[[Gaia (spacecraft)|Gaia]]'' [[astrometry]] mission was launched as one of three missions in the Horizon 2000 Plus campaign.]] |

||

''Horizon 2000 Plus'' was an extension of Horizon 2000 programme prepared in the mid-1990s. This included two further cornerstone missions, the star-mapping [[Gaia_(spacecraft)|GAIA]] launched in 2013, and the [[BepiColombo]] mission to Mercury launched in 2018; and also a technology demonstrator [[LISA Pathfinder]] launched in 2015, to test technologies for the future [[Laser Interferometer Space Antenna|LISA]]. |

''Horizon 2000 Plus'' was an extension of Horizon 2000 programme prepared in the mid-1990s, planning missions in the 1995–2015 timeframe.<ref name="horizon2000-figure" /> This included two further cornerstone missions, the star-mapping [[Gaia_(spacecraft)|GAIA]] launched in 2013, and the [[BepiColombo]] mission to Mercury launched in 2018; and also a technology demonstrator [[LISA Pathfinder]] launched in 2015, to test technologies for the future [[Laser Interferometer Space Antenna|LISA]]. |

||

All of the Horizon 2000 and Plus missions were successful, except for the first [[Cluster_(spacecraft)|Cluster]] which was destroyed in 1996 when its launch rocket exploded. A replacement, [[Cluster 2]], was built and launched successfully in 2000. |

All of the Horizon 2000 and Plus missions were successful, except for the first [[Cluster_(spacecraft)|Cluster]] which was destroyed in 1996 when its launch rocket exploded. A replacement, [[Cluster 2]], was built and launched successfully in 2000. |

||

Revision as of 18:34, 8 July 2019

A request that this article title be changed to Cosmic Vision is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Yiosie2356 (talk | contribs) 4 years ago. (Update timer) |

The Science Programme[1][2][a] of the European Space Agency is a long-term programme of space science and space exploration missions. Managed by the agency's Directorate of Science, The programme funds the development, launch, and operation of missions led by European space agencies and institutions through generational campaigns. Horizon 2000, the programme's first campaign, facilitated the development of eight missions between 1985 and 1995 including four "cornerstone missions" – SOHO and Cluster II, XMM-Newton, Rosetta, and Herschel. Horizon 2000 Plus, the programme's second campaign, facilitated the development of Gaia, LISA Pathfinder, and BepiColombo between 1995 and 2005. The programme's current campaign since 2005, Cosmic Vision, has so far funded the development of ten missions including three flagship missions, JUICE, ATHENA, and LISA. The programme's upcoming fourth campaign, Voyage 2050, is currently being drafted. Collaboration with agencies and institutions outside of Europe occasionally occur in the Science Programme, including a collaboration with NASA on Cassini–Huygens and the CNSA on SMILE.

Governance

| ESA Science Programme advisory structure[8][9][10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Science Programme is managed by the European Space Agency (ESA)'s Directorate of Science,[11] and its goals include the proliferation of Europe's scientific presence in space, fostering technological innovation, and maintaining European space infrastructure such as launch services and spacecraft operations.[11] It is one of ESA's mandatory programmes, in which each member state of ESA must participate.[12][13] Members contribute an amount proportional to their net national product to ensure the long-term financial security of the programme and its missions.[13][14] The programme's planning structure is a "bottom up" process that allows the European scientific community to control the direction of the programme through advisory bodies.[7][15] These bodies make recommendations on the programme to the Director General and the Director of Science,[16][17] and their recommendations are independently reported to ESA's Science Programme Committee (SPC) – the authority over the programme as a whole.[16][18] The programme's current advisory structure consists the Astronomy Working Group (AWG) and the Solar System and Exploration Working Group (SSEWG),[8][9] who report to the senior Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC) that reports to the agency's directors.[17] Membership on the advisory bodies last three years,[19] and the chairs of the AWG and SSEWG are also members of the SSAC.[8][9][19] Ad hoc advisory groups may also be created to advise on certain mission proposals or the formulation of planning cycles.[10]

Missions in the programme are selected through competitions in which members of the European scientific community submit proposals to ESA.[20] During each competition, the agency outlines one of four mission categories for which proposals need to meet the criteria of;[21] these are the "L"-class large missions, the "M"-class medium missions, the "S"-class small missions, and the "F"-class fast missions, each with differing budget caps and implementation timelines.[5][21] The proposals are then reviewed by the AWG, SSEWG, engineers at ESA, and any relevant ad hoc working groups, as part of a feasibility study known as "Phase 0".[22][23] Missions which require new technologies to be developed are reviewed during these studies at the Concurrent Design Facility at the European Space Research and Technology Centre.[24] After the study, up to three proposals are selected as finalists in "Phase A", in which a preliminary design for each candidate mission is formulated.[23][25] The SPC then makes a final decision on which proposal proceeds to phases "B" through "F", which include the development, construction, launch, and disposal of the spacecraft used in the mission.[26][27][28] During Phase A, each candidate mission is assigned two competing contractors to build their spacecraft, and the contractor for the winning mission is chosen during Phase B.[25][27]

History

Background

The European Space Agency (ESA) was established in May 1975 as the merger of the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) and the European Launcher Development Organisation.[29][30][31] In 1970, the governing Launch Programme Advisory Committee (LPAC) of ESRO made a decision not to execute astronomy or planetary missions, which were perceived as beyond the budget and capabilities of the organisation at the time.[32][33] This meant that cooperation with other government space agencies and institutions was necessary for large-scale scientific missions.[33] This policy was effectively reversed in 1980, when ESA's then-Director of Science, Ernst Trendelenburg, and the agency's new authoritative Science Programme Committee (SPC) selected the Giotto flyby reconnaissance mission to comet Halley and the Hipparcos astrometry mission for launch.[34][35] In addition to the selection of the International Ultraviolet Explorer telescope in March 1983,[35] the three were the first European science missions launched aboard Arianespace launch vehicles, which gave Europe autonomy over its launch services.[36][37] This, in addition to the lack of a long-term plan for scientific missions, along with budget setbacks from NASA on the collaborative International Solar Polar Mission (later christened Ulysses),[38] spurred the development of a long-term scientific programme through which ESA could sustainably plan missions independent of other agencies and institutions over lengthier periods.[38][39] The leadership and advisory structure of ESA's Directorate of Science changed immediately prior to the programme's establishment. In the 1970s, ESA's Science Advisory Committee (SAC), which succeeded the LPAC, advised the Director General on all scientific matters; the Astronomy Working Group (AWG) and the Solar System Working Group (SSWG) also reported directly to the Director General.[40] In the early 1980s, the SAC was replaced with the Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC), who were tasked to report to the Director of Science on developments in the AWG and SSWG.[41] In addition, former SAC chair Roger-Maurice Bonnet replaced Trendelenburg as Director of Science in May 1983.[42]

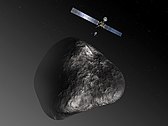

Horizon 2000

Horizon 2000 was the first programme focused on science missions. It was drafted by the European Space Agency in 1984, which wanted a dedicated focus on funding and developing new science missions while also maintaining contemporary ones.[43] The program, while providing funding for already-launched missions and those in late development such as the International Ultraviolet Explorer, Hipparcos and Ulysses, supported a series of brand new missions, divided into large-budget ventures known as "cornerstone" missions, and medium-sized missions known colloquially as "blue missions".[43] The plan originally called for three cornerstone missions throughout the scope of the programme, spanning the 1985–2005 timeframe.[44] However, the Solar-Terrestrial Science Programme, which consisted of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and Cluster missions, was adopted into the Horizon 2000 plan, leading the two missions to become Cornerstone 1 of what became four cornerstone missions.[45] XMM-Newton was selected as the second cornerstone mission of the programme, while Rosetta and FIRST were selected in November 1993 as the third and fourth cornerstone missions,[46] with the latter mission eventually being rechristened the Herschel Space Observatory.

Part of the Horizon 2000 programme was also a class of medium-sized missions known as "blue missions" – their name deriving from the colour of the box that represents them in the original Horizon 2000 proposal diagram from 1984.[47] The Huygens lander, a component of the Cassini–Huygens mission, became the first designated medium-sized mission of the Horizon 2000 programme, after its selection in November 1988.[47] INTEGRAL was chosen as the succeeding medium-sized mission in June 1993,[48] followed three years later by the selection of COBRAS/SAMBA, later rechristened Planck, as the third medium-sized mission in July 1996.[49][50] As of December 2016, four Horizon 2000 missions, including three cornerstone and one medium-sized mission, remain operational.

Horizon 2000 Plus

Horizon 2000 Plus was an extension of Horizon 2000 programme prepared in the mid-1990s, planning missions in the 1995–2015 timeframe.[44] This included two further cornerstone missions, the star-mapping GAIA launched in 2013, and the BepiColombo mission to Mercury launched in 2018; and also a technology demonstrator LISA Pathfinder launched in 2015, to test technologies for the future LISA.

All of the Horizon 2000 and Plus missions were successful, except for the first Cluster which was destroyed in 1996 when its launch rocket exploded. A replacement, Cluster 2, was built and launched successfully in 2000.

Cosmic Vision

Cosmic Vision 2015–2025 is the current programme of ESA's long-term planning for space science missions. The initial call of ideas and concepts was launched in 2004 with a subsequent workshop held in Paris to define more fully the themes of the Cosmic Vision under the broader subjects of astronomy and astrophysics, Solar System exploration and fundamental physics. By early 2006 the formulation for a 10-year plan based around 4 key questions emerged:

- What are the conditions for planet formation and the emergence of life?

- How does the Solar System work?

- What are the fundamental physical laws of the Universe?

- How did the Universe originate and what is it made of?

In March 2007 a call for mission ideas was formally released, which yielded 19 astrophysics, 12 fundamental physics and 19 Solar System mission proposals. In March 2012 ESA announced it had begun working on a series of small class (S-class) science missions. The first winning S-class concept is set to receive 50 million euros (£42m) and will be readied for launch in 2017.[51][needs update]

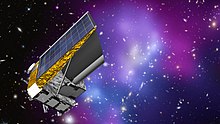

Large class (L-class) missions were originally intended to be carried out in collaboration with other partners with an ESA-specific cost not exceeding 900 million euros. However, in April 2011 it became clear that budget pressures in the US meant that an expected collaboration with NASA on the L1 mission would not be practical. The down-selection was therefore delayed and the missions re-scoped on the assumption of ESA leadership with some limited international participation.[52] Three L-class missions have been selected under Cosmic Vision: JUICE, a Jupiter and Ganymede orbiter planned for launch in 2022;[53] ATHENA, an X-ray observatory planned for launch in 2031;[54][55] and LISA, a space-based gravitational-wave observatory planned for launch in 2034.[56][57]

Medium class (M-class) projects are relatively stand-alone projects and have a price cap of approximately 500 million euros. The first two M-class missions, the Solar Orbiter heliophysics mission to make close-up observations of the Sun,[58] and the Euclid visible to near-infrared space telescope, aimed at studying dark energy and dark matter,[59] were selected in October 2011.[60] PLATO, a mission to search for exoplanets and measure stellar oscillations, was selected on 19 February 2014,[57] against EChO, LOFT, MarcoPolo-R and STE-QUEST[61] After a preliminary culling of proposals for the fourth M-class mission in March 2015, a short list of three mission proposals selected for further study was announced on 4 June 2015.[62][63][64] The shortlist included the THOR plasma observatory and the XIPE X-ray observatory.[64] ARIEL, a space observatory which will observe transits of nearby exoplanets to determine their chemical composition and physical conditions,[64] was ultimately selected on 20 March 2018.[65][66] The competition for the fifth M-class mission is currently underway, with the SPICA far-infrared observatory, THESEUS gamma-ray observatory, and EnVision Venus orbiter chosen as finalists. The winning candidate will be selected in 2021.[67]

Small class missions (S-class) are intended to have a cost to ESA not exceeding 50 million euros. A first call for mission proposals was issued in March 2012.[68] Approximately 70 letters of Intent were received.[69] In October 2012 the first S-class mission was selected.[70] Cosmic Vision's S-class includes CHEOPS, a mission to search for exoplanets by photometry,[71] and SMILE, a joint mission between ESA and the Chinese Academy of Sciences to study the interaction between Earth's magnetosphere and the solar wind, which was selected in June 2015 from thirteen competing proposals.[72][73]

At the ESA Science Programme Committee (SPC) Workshop on 16 May 2018, the creation of a series of special opportunity Fast class (F-class) missions was proposed. These F-class missions will be jointly launched alongside each M-class mission starting from M4, and would focus on "innovative implementation" in order to broaden the range of scientific topics covered by the mission. The inclusion of F-class missions into the Cosmic Vision program will require an increase of the science budget.[74] F-class missions must take under a decade from selection to launch and weigh less than 1,000 kg.[75] The first F-class mission, Comet Interceptor, was selected in June 2019.[76][77]

Occasionally ESA makes contributions to space missions led by another space agency. Missions of opportunity allow the ESA science community to participate in partner-led missions at relatively low cost. The cost of a mission of opportunity is capped at €50 million.[78] ESA missions of opportunity include contributions to Hinode, IRIS, MICROSCOPE, PROBA-3, XRISM, ExoMars, Einstein Probe, and MMX.[78] A contribution to SPICA (Space Infrared Telescope for Cosmology and Astrophysics), a Japanese JAXA mission, was evaluated as a mission of opportunity within Cosmic Vision. It is no longer considered within that framework,[79] though SPICA is now one of the mission proposals being considered for M5.

Voyage 2050

The next campaign of the ESA science programme is Voyage 2050, which will cover space science missions operating from 2035 to 2050. Planning began with the appointment of a Senior Committee in December 2018 and a call for white papers in March 2019.[80]

Three Large class and six to seven Medium class missions are currently anticipated in this plan, as well as smaller missions and missions of opportunity. It will be the responsibility of the Senior Committee and assisting topical teams to evaluate white papers and publish a final report detailing the Voyage 2050 plan by the end of 2020.[81]

Missions

Horizon 2000

- Cornerstone 1 – SOHO, launched December 1995, operational – Joint ESA-NASA Solar observation mission providing real-time data for space weather forecasting.

- Cornerstone 1 – Cluster, launched June 1996, failed – Earth observation mission using four identical spacecraft to study the planet's magnetosphere. Failed on launch.

- Re-launch – Cluster II, launched July and August 2000, operational – Successful replacement mission.

- Cornerstone 2 – XMM-Newton, launched December 1999, operational – An X-ray space observatory, studying the full range of cosmic X-ray sources.

- Cornerstone 3 – Rosetta, launched March 2004, completed – 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko orbiter mission, studying comets and their evolution.

- Cornerstone 4 – Herschel, launched May 2009, completed – Infrared space observatory mission for general astronomy.

- Medium 1 – Huygens, launched October 1997, completed – Titan lander component of the Cassini–Huygens mission; first landing in the outer solar system.

- Medium 2 – INTEGRAL, launched October 2002, operational – Gamma ray space observatory, also capable of observing X-ray and visible wavelengths.

- Medium 3 – Planck, launched May 2009, completed – Cosmology mission that mapped the cosmic microwave background and its anisotropies.

Horizon 2000 Plus

- Mission 1 – Gaia, launched December 2013, operational – Astrometry mission measuring positions and distances of over one billion objects in the Milky Way.

- Mission 2 – LISA Pathfinder, launched December 2015, completed – Demonstration of technologies for the Cosmic Vision LISA Gravitational-wave observatory mission.

- Mission 3 – BepiColombo, launched October 2018, operational – Joint ESA-JAXA reconnaissance mission to Mercury, using two unique spacecrafts operating respectively.

Cosmic Vision

- L1 – JUICE, launching June 2022, with an orbital insertion in 2030. future – Jupiter orbiter mission, focused on studying the Galilean moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

- L2 – ATHENA, launching 2031, future – X-ray space observatory mission, designed as a successor to the XMM-Newton telescope.

- L3 – LISA, launching 2034, future – the first dedicated gravitational wave space observatory mission.

- M1 – Solar Orbiter, launching February 2020, future – Solar observatory mission, designed to perform in-situ studies of the Sun at a perihelion of 0.28 astronomical units.

- M2 – Euclid, launching June 2022, future – Visible and near-infrared space observatory mission focused on dark matter and dark energy.

- M3 – PLATO, launching 2026, future – Kepler-like space observatory mission, aimed at discovering and observing exoplanets.

- M4 – ARIEL, launching 2028, future – Planck-based space observatory mission studying the atmosphere of known exoplanets.

- S1 – CHEOPS, launching October or November 2019, future – Space observatory mission focused on studying known exoplanets.

- S2 – SMILE, launching 2023, future – Joint ESA-CAS Earth observation mission, studying the interaction between the planet's magnetosphere and solar wind.

- F1 – Comet Interceptor, launching in 2028, future

Timeline

See also

- List of European Space Agency programs and missions

- List of Solar System probes

- List of space telescopes

- Living Planet Programme

References

Notes

Sources

- Bonnet, Roger-Maurice [in French] (1995). "European Space Science - In Retrospect and in Prospect". In Battrick, Bruce; Guyenne, Duc; Mattok, Clare (eds.). ESA Bulletin No. 81. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. pp. 6–17. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Bonnet, Roger-Maurice [in French] (2004). "Cassini–Huygens in the European Context". In Fletcher, Karen (ed.). Titan: From Discovery to Encounter: Proceedings of the International Conference, 13-17 April 2004, ESTEC, Noordwijk, the Netherlands. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. pp. 201–209. ISBN 9789290929970. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Cogen, Marc (2016). An Introduction to European Intergovernmental Organizations (2nd ed.). Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 9781317181811. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - European Science Foundation; National Research Council (1998). U.S.-European Collaboration in Space Science. Washington, D.C., United States: National Academies Press. ISBN 9780309059848. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - European Space Agency (1995). "The Science Programme". The ESA Programmes (BR-114). Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - European Space Agency (2013). "How a Mission is Chosen". ESA Science. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - European Space Agency (2015). "Science Programme". ESA Industry Portal. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Krige, John; Russo, Arturo; Sebesta, Laurenza (2000). Harris, R. A. (ed.). A History of the European Space Agency, 1958 – 1987 (Vol. II - The Story of ESA, 1973 to 1987) (PDF). Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. ISBN 9789290925361. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Citations

- ^ "ESA science programme planning cycles". ESA Science. 4 March 2019. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

The Science Programme of the European Space Agency (ESA) relies on long-term planning of its scientific priorities.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ ESA 2015, "The Science Programme within the Directorate of Science has two main objectives [...] The Science Programme has a long and successful history..."

- ^ ESA Media Relations Office (12 October 2012). "ESA Science Programme's new small satellite will study super-Earths". European Space Agency. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

Studying planets around other stars will be the focus of the new small Science Programme mission, Cheops, ESA announced today. [...] The mission was selected from 26 proposals submitted in response to the Call for Small Missions in March [...] Possible future small missions in the Science Programme should be low cost and rapidly developed, in order to offer greater flexibility in response to new ideas from the scientific community.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ ESA 1995, "ESA's Science Programme has three primary features that single it out among the Agency's activities [...] ESA's Science Programme has consistently focussed on missions with a strong innovative content."

- ^ a b "Call for a Fast (F) mission opportunity in ESA's Science Programme". ESA Science. 16 July 2018. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

This Call for a Fast mission aims at defining a mission of modest size (wet mass less than 1000 kg) to be launched towards the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point as a co-passenger to the ARIEL M mission, or possibly the PLATO M mission.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ ESA 2013, "The ESA scientific programme is based on a continuous flow of projects that fulfil its scientific goals."

- ^ a b ESF and NRC 1998, page 36, "The fundamental rule of ESRO, and subsequently ESA, has been that ESA exists to serve scientists and that its science policy must be driven by the scientific community, not vice versa [...] [This] explains the determining influence that ESA's advisory structure has on the definition and evolution of the scientific program."

- ^ a b c European Space Agency (2011). "Astronomy Working Group". ESA Cosmos Portal. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

The Astronomy Working Group (AWG) provides scientific advice mainly to the Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC). [...] The chair of the working group is also a member of the SSAC.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c European Space Agency (2011). "Solar System and Exploration Working Group (SSEWG)". ESA Cosmos Portal. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

The Solar System and Exploration Working Group (SSEWG) provide scientific advice mainly to the Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC). [...] The chair of the working group is also a member of the SSAC.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b ESF and NRC 1998, page 36, "Ad hoc working groups may also by appointed to advise on particular subjects. [...] Another was the so-called survey committee, which formulated the long-term plan for space science (i.e., the Horizon 2000 program) on the basis of input contributed by the European scientific community."

- ^ a b ESA 2015, "The Science Programme within the Directorate of Science has two main objectives; To provide the scientific community with the best tools possible to maintain Europe's competence in space; To contribute to the sustainability of European space capabilities and associated infrastructures by fostering technological innovation in industry and science communities, and maintaining launch services and spacecraft operations."

- ^ Cogen 2016, page 221, "All member states must participate in the mandatory programmes [...] Today, ESA's mandatory programmes are carried out under the General Budget, the Technology Research Programme, the Science Programme and ESA's technical and operational infrastructure."

- ^ a b ESA 1995, "...it is the only mandatory programme [...] In 1975, when ESRO and ELDO were merged to form ESA, it was immediately decided that the Agency's Science Programme should be mandatory."

- ^ ESA 2015, "All Member States contribute pro-rata to their Net National Product (NNP) providing budget stability and allowing long-term planning of its scientific goals. For this reason, the Science Programme is called 'mandatory'.

- ^ ESA 2015, "Long-term science planning and mission calls are established through bottom-up processes. This relies on broad participation, with input and peer reviews of the space science community. The ESA Science Programme is foremost science-driven."

- ^ a b ESF and NRC 1998, page 36, "They advise the director general and the director of the scientific program on all scientific matters, and their recommendations are independently reported to the SPC."

- ^ a b European Space Agency (2011). "Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC)". ESA Cosmos Portal. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

The Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC) is the senior advisory body to the Director of Science (D/SCI) on all matters concerning space science included in the mandatory science programme of ESA.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cogen 2016, page 219, "The Council is responsible for the establishment of a Science Programme Committee which deals with any matter relating to the mandatory scientific programme."

- ^ a b ESF and NRC 1998, page 36, "Membership on the advisory bodies is for 3 years, and the chairs of the AWG and SSWG are de jure members of the SSAC."

- ^ ESA 2013, "These projects are identified and selected using the mechanism of the open call. Whenever appropriate, and compatible with the programme goals and constraints, ESA issues a call for proposals for new science missions."

- ^ a b ESA 2013, "The call includes descriptions of the scientific goals, size, cost of the mission, together with programmatic and implementation details. [...] Missions fall into three categories: small (S-class), medium (M-class) and large (L-class), their size reflecting the scientific goals addressed and eventually the cost and development time required."

- ^ ESA 2013, "ESA's various scientific advisory committees of experts assess the submissions. [...] ESA’s engineers also make an initial assessment of the feasibility of the missions. [...] Phase 0; Mission analysis and identification..."

- ^ a b Bonnet 2004, page 203, "Following a normal cycle of selection, through the Working Group, ESA undertook a feasibility study in 1984-1985, followed by the selection for Phase A in 1986."

- ^ ESA 2013, "This identifies any new technology that will need to be developed to make the mission possible. The majority of these studies are conducted internally at ESA's Concurrent Design Facility (CDF)."

- ^ a b ESA 2013, "The committees then make recommendations about which missions should proceed to 'Phase A'. [...] Usually two or three missions are downselected for the phase A study, for which two competitive industrial contracts are placed for each mission. Phase A results in a preliminary design for the mission."

- ^ ESA 2013, "Phase B; Preliminary Definition; Phase C; Detailed Definition; Phase D; Qualification and Production; Phase E; Utilisation; Phase F; Disposal..."

- ^ a b ESA 2013, "Results are presented, again in Paris to the various committees, and a final decision on which proposal will be selected for each mission is made. [...] They will eventually lead to the 'adoption' of the mission and to the selection of one of the two industrial contractors to become the responsible for the whole implementation phase..."

- ^ Bonnet 2004, page 203–204, "The Titan Probe was eventually selected by ESA's SCP in Nov. 1988 as the first 'blue' mission of Horizon 2000, against four other missions: VESTA, LYMAN, QUASAT, and GRASP."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000, page 34, "The Convention establishing the European Space Agency was signed by ten European states on 30 May 1975 [...] At the same time the Conference of Plenipotentiaries adopted a Final Act including ten resolutions. These made allowance for the transition from ESRO and ELDO to ESA..."

- ^ Cogen 2016, page 217, "ESA is created in its current form in 1975, merging ELDO with ESRO, by the Convention for the Establishment of a European Space Agency of 30 May 1975."

- ^ Parks, Clinton (27 May 2008). "May 31, 1975: European Space Unites Under the ESA Banner". SpaceNews. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

Established May 31, 1975, ESA formed from the merger of the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) and the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO).

- ^ Krige et al. 2000, page 40, "Astronomy had suffered heavily in ESRO and had been explicitly demoted in priority by the LPAC in 1970."

- ^ a b Bonnet 2004, page 201, "At their long term planning meeting in 1970, the LPAC decided not to plan any planetary missions because they were considered at the time too expensive and beyond the financial capabilities of ESRO. Cooperation with NASA or the USSR was the only option for Europe to participate in the exploration of the Solar System."

- ^ Bonnet 2004, page 201–202, "The first change from that policy was the proposal of the ESA Science Director, Ernst Trendelenburg, followed by the positive decision of ESA's SPC in 1980, to launch a fast fly-by mission to Halley's comet on the occasion of its return to the vicinity of the Sun in March 1986."

- ^ a b Bonnet 1995, page 9, "These two events together explain the series of decisions taken between 1980 and 1983. Giotto and Hipparcos were selected by the SPC in 1980 (again with great difficulties in deciding between astronomy and solar-system missions) and ISO in March 1983."

- ^ Bonnet 1995, page 9, "The crisis came in the same period as the arrival of Ariane, which was successfully launched for the first time on Christmas Eve 1979, giving Europe full autonomy in accessing space. [...] All three missions were to use the Ariane launcher and were originally European-only missions."

- ^ Bonnet 2004, page 202, "Giotto (the name given to that mission) was the first purely European mission to explore the Solar System with its own launcher: Ariane 1, launched on July 2 1985."

- ^ a b Bonnet 1995, page 9, "The ISPM crisis then opened their eyes as they realised for the first time the fragility of agreements signed by their trans- Atlantic counterparts. The Memorandum of Understanding, the official document establishing the basis for the cooperation, which had a binding significance on the European side, had a different interpretation for the Americans, with NASA's budget submitted to yearly discussion at the White House and in Congress."

- ^ Bonnet 1995, page 10, "In 1983, it became clear that ESA could no longer continue with its existing method of selecting project after project, without a long-term perspective and some kind of commitment that would allow the scientific community to prepare itself better for the future. ESA too needed a long-term programme in space science."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000, page 39, "The DG replaced the LPAC with the SAC (Science Advisory Committee) reporting directly to him on all scientific matters [...] A Life Sciences Working Group (LSWG) and Materials Sciences Working Group (MSWG) were also added to the AWG and SSWG, with all working groups reporting to the DG."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000, page 43, "The SAC, which had previously advised the Director General on all scientific matters, was now transformed into the SSAC (Space Science Advisory Committee). Its role became to advise the Director of Scientific Programmes on activities covered by the AWG and the SSWG."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000, page 43, "The spirited and controversial figure of Ernst Trendelenburg, who had spent almost twenty years in ESRO and then ESA, was replaced as Director of Scientific Programmes on 1 May 1983 by the French space scientist Roger Bonnet, former chairman of the SAC from 1978 to 1980."

- ^ a b Bonnet, R. M. (August 1990). "ESA's 'Horizon 2000' Programme". Esa Special Publication. 310: 167–173. Bibcode:1990ESASP.310..167B.

- ^ a b Vincent Minier; et al. Inventing a Space Mission: The Story of the Herschel Space Observatory. Springer Publishing. p. 40. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60024-9. ISBN 978-3-319-60023-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ European Science Foundation; National Research Council (1998). U.S. – European Collaboration in Space Science. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. p. 52. Bibcode:1998usec.book.....N. ISBN 978-0-309-05984-8.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "ESA confirms ROSETTA and FIRST in its long-term science programme". Xmm-Newton Press Release: 43. 8 November 1993. Bibcode:1993xmm..pres...43. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Karen; Bonnet, Roger-Maurice (2004). Titan – from discovery to encounter: Proceedings of the International Conference; 13 – 17 April 2004, ESTEC, Noordwijk, the Netherlands. Vol. 1278. Noordwijk: ESA Publications Division. p. 201. Bibcode:2004ESASP1278..201B. ISBN 978-92-9092-997-0.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "INTEGRAL (INTErnational Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Lab)". Image Processing Laboratory. University of Valencia. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Van Tran, J. (1998). Fundamental Parameters in Cosmology. Paris: Atlantica Séguier Frontières. p. 255. ISBN 978-2-86332-233-8.

- ^ "History of Planck - COBRAS/SAMBA: The Beginning of Planck". ESA Cosmos Portal. European Space Agency. December 2013. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (12 March 2012). "Esa to start mini space mission series". BBC. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "New approach for L-class mission candidates". ESA. 19 April 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "JUICE is Europe's next large science mission". ESA. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "ESA Science & Technology: Athena to study the hot and energetic Universe". ESA. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "ATHENA: Mission Summary". ESA. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Guido Mueller (22 August 2014). "Prospects for a space-based gravitational-wave observatory". SPIE Newsroom. SPIE. doi:10.1117/2.1201408.005573. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Gravitational wave mission selected, planet-hunting mission moves forward". ESA. 20 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "Solar Orbiter: Summary". ESA. 20 September 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "Key milestone for Euclid mission, now ready for final assembly". ESA. 18 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "Dark and bright: ESA chooses next two science missions". ESA. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "ESA selects planet-hunting PLATO mission". ESA. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Call for a Medium-size mission opportunity in ESA's Science Programme for a launch in 2025 (M4)". ESA. 19 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Europe drops asteroid sample-return idea". BBC. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ a b c "Three candidates for ESA's next medium-class science mission". ESA. 4 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "ESA's next science mission to focus on nature of exoplanets". esa.int. 20 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "COSMIC VISION M4 CANDIDATE MISSIONS: PRESENTATION EVENT". ESA. 5 May 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "ESA selects three new mission concepts for study". ESA. 7 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ "Call for a small mission opportunity in ESA's science programme for a launch in 2017". ESA. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "S-class mission letters of intent". ESA. 16 April 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "CHEOPS Mission Status & Summary". July 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Exoplanet mission launch slot announced". ESA. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "ESA and Chinese Academy of Sciences to study SMILE as joint mission". ESA. 4 June 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "SMILE: Summary". UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Hasinger, Günther (23 May 2018). "The ESA Science Programme - ESSC Plenary Meeting" (PDF). ESA. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ Comet mission given green light by European Space Agency. Will Gater, Physics World. 21 June 2019.

- ^ ESA to Launch Comet Interceptor Mission in 2028. Emily Lakdawalla, The Planetary Society. June 21, 2019.

- ^ European Comet Interceptor Could Visit an Interstellar Object. Jonathan O'Callaghan, Scientific American. 24 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Policy for Missions of Opportunity in the ESA Science Directorate". ESA. 5 February 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ "SPICA - A space infrared telescope for cosmology and astrophysics". ESA. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "Voyage 2050 – Long-term planning of the ESA Science Programme". ESA. 28 February 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ "Call for White Papers for the Voyage 2050 long-term plan in the ESA Science Programme". ESA. 4 March 2019. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- ESA Science Programme Planning Cycles at the European Space Agency

- Space Science at the European Space Agency