Bladder cancer: Difference between revisions

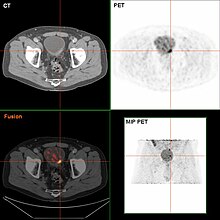

Treatment failure after trimodal therapy. |

passive smoking also is a risk for bladder cancer |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

==Causes== |

==Causes== |

||

[[Tobacco]] [[smoking]] is the main known contributor to urinary bladder cancer; in most populations, smoking is associated with over half of bladder cancer cases in men and one-third of cases among women,<ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<630::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-Q |author=Zeegers MP |last2=Tan |first2=FE |last3=Dorant |first3=E |last4=Van Den Brandt |first4=PA |title=The impact of characteristics of cigarette smoking on urinary tract cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies |journal=Cancer |volume=89 |issue=3 |pages=630–9 |year=2000 |pmid=10931463|url=https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/portal/en/publications/the-impact-of-characteristics-of-cigarette-smoking-on-urinary-tract-cancer-risk-a-metaanalysis-of-epidemiologic-studies(01f8bed8-20fb-4f9d-8980-73eb7e24ccc2).html }}</ref> however these proportions have reduced over recent years since there are fewer smokers in Europe and North America.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Osch|first=Frits H. M. van|last2=Jochems|first2=Sylvia H. J.|last3=Schooten|first3=Frederik-Jan van|last4=Bryan|first4=Richard T.|last5=Zeegers|first5=Maurice P.|date=2016-04-20|title=Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies|url=http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2016/04/20/ije.dyw044|journal=International Journal of Epidemiology|volume=45|issue=3|language=en|pages=857–870|doi=10.1093/ije/dyw044|issn=0300-5771|pmid=27097748}}</ref> There is an almost linear relationship between smoking duration (in years), [[Pack-year|pack years]] and bladder cancer risk. A risk plateau at smoking about 15 cigarettes a day can be observed (meaning that those who smoke 15 cigarettes a day are approximately at the same risk as those smoking 30 cigarettes a day). Quitting smoking reduces the risk, however former smokers will most likely always be at a higher risk of bladder cancer compared to people who have never smoked.<ref name=":0" /> Passive smoking |

[[Tobacco]] [[smoking]] is the main known contributor to urinary bladder cancer; in most populations, smoking is associated with over half of bladder cancer cases in men and one-third of cases among women,<ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<630::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-Q |author=Zeegers MP |last2=Tan |first2=FE |last3=Dorant |first3=E |last4=Van Den Brandt |first4=PA |title=The impact of characteristics of cigarette smoking on urinary tract cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies |journal=Cancer |volume=89 |issue=3 |pages=630–9 |year=2000 |pmid=10931463|url=https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/portal/en/publications/the-impact-of-characteristics-of-cigarette-smoking-on-urinary-tract-cancer-risk-a-metaanalysis-of-epidemiologic-studies(01f8bed8-20fb-4f9d-8980-73eb7e24ccc2).html }}</ref> however these proportions have reduced over recent years since there are fewer smokers in Europe and North America.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Osch|first=Frits H. M. van|last2=Jochems|first2=Sylvia H. J.|last3=Schooten|first3=Frederik-Jan van|last4=Bryan|first4=Richard T.|last5=Zeegers|first5=Maurice P.|date=2016-04-20|title=Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies|url=http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2016/04/20/ije.dyw044|journal=International Journal of Epidemiology|volume=45|issue=3|language=en|pages=857–870|doi=10.1093/ije/dyw044|issn=0300-5771|pmid=27097748}}</ref> There is an almost linear relationship between smoking duration (in years), [[Pack-year|pack years]] and bladder cancer risk. A risk plateau at smoking about 15 cigarettes a day can be observed (meaning that those who smoke 15 cigarettes a day are approximately at the same risk as those smoking 30 cigarettes a day). Quitting smoking reduces the risk, however former smokers will most likely always be at a higher risk of bladder cancer compared to people who have never smoked.<ref name=":0" /> Passive smoking also appear to be a risk.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Yan |first1=H |last2=Ying |first2=Y |last3=Xie |first3=H |last4=Li |first4=J |last5=Wang |first5=X |last6=He |first6=L |last7=Jin |first7=K |last8=Tang |first8=J |last9=Xu |first9=X |last10=Zheng |first10=X |title=Secondhand smoking increases bladder cancer risk in nonsmoking population: a meta-analysis. |journal=Cancer management and research |date=2018 |volume=10 |pages=3781-3791 |doi=10.2147/CMAR.S175062 |pmid=30288109 |accessdate=21 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Health Risks of Secondhand Smoke |url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/tobacco-and-cancer/secondhand-smoke.html |website=www.cancer.org |accessdate=21 November 2019 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

Thirty percent of bladder tumors probably result from occupational exposure in the workplace to carcinogens such as [[benzidine]]. [[2-Naphthylamine]], which is found in cigarette smoke, has also been shown to increase bladder cancer risk. Occupational or circumstantial exposure to the following substances has also been implicated as a cause of bladder cancer; 4-aminobiphenyl (rubber industry), β-naphtylamine (rubber industry), phenacetin (analgesic), arsenic in drinking water, auramine (dye manufacturing), magenta (dye manufacturing), ortho-toluidine (dye manufacturing), epoxy and polyurethane resin hardening agents (plastics industry), [[chlornaphazine]], coal-tar pitch.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Humans |first1=IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to |title=4-AMINOBIPHENYL |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304408/ |publisher=International Agency for Research on Cancer |language=en |date=2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Saint-Jacques |first1=N |last2=Parker |first2=L |last3=Brown |first3=P |last4=Dummer |first4=TJ |title=Arsenic in drinking water and urinary tract cancers: a systematic review of 30 years of epidemiological evidence. |journal=Environmental Health |date=2 June 2014 |volume=13 |pages=44 |doi=10.1186/1476-069X-13-44 |pmid=24889821|pmc=4088919 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Clin |first1=B |last2="RecoCancerProf" Working |first2=Group. |last3=Pairon |first3=JC |title=Medical follow-up for workers exposed to bladder carcinogens: the French evidence-based and pragmatic statement. |journal=BMC Public Health |date=6 November 2014 |volume=14 |pages=1155 |doi=10.1186/1471-2458-14-1155 |pmid=25377503|pmc=4230399 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Humans |first1=IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to |title=CHLORNAPHAZINE |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304335/ |publisher=International Agency for Research on Cancer |language=en |date=2012}}</ref> Occupations at risk are bus drivers, rubber workers, painters, motor mechanics, leather (including shoe) workers, blacksmiths, machine setters, and mechanics.<ref>{{Cite journal|vauthors=Reulen RC, Zeegers MP |title=A meta-analysis on the association between bladder cancer and occupation |journal=Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. Supplementum |volume= 42|issue=218 |pages=64–78 |date=September 2008 |pmid=18815919 |doi=10.1080/03008880802325192}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Guha |first1=N |last2=Steenland |first2=NK |last3=Merletti |first3=F |last4=Altieri |first4=A |last5=Cogliano |first5=V |last6=Straif |first6=K |title=Bladder cancer risk in painters: a meta-analysis. |journal=Occupational and Environmental Medicine |date=August 2010 |volume=67 |issue=8 |pages=568–73 |doi=10.1136/oem.2009.051565 |pmid=20647380}}</ref> Hairdressers are thought to be at risk as well because of their frequent exposure to permanent hair dyes.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Harling |first1=M |last2=Schablon |first2=A |last3=Schedlbauer |first3=G |last4=Dulon |first4=M |last5=Nienhaus |first5=A |title=Bladder cancer among hairdressers: a meta-analysis. |journal=Occupational and Environmental Medicine |date=May 2010 |volume=67 |issue=5 |pages=351–8 |doi=10.1136/oem.2009.050195 |pmid=20447989|pmc=2981018 }}</ref> |

Thirty percent of bladder tumors probably result from occupational exposure in the workplace to carcinogens such as [[benzidine]]. [[2-Naphthylamine]], which is found in cigarette smoke, has also been shown to increase bladder cancer risk. Occupational or circumstantial exposure to the following substances has also been implicated as a cause of bladder cancer; 4-aminobiphenyl (rubber industry), β-naphtylamine (rubber industry), phenacetin (analgesic), arsenic in drinking water, auramine (dye manufacturing), magenta (dye manufacturing), ortho-toluidine (dye manufacturing), epoxy and polyurethane resin hardening agents (plastics industry), [[chlornaphazine]], coal-tar pitch.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Humans |first1=IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to |title=4-AMINOBIPHENYL |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304408/ |publisher=International Agency for Research on Cancer |language=en |date=2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Saint-Jacques |first1=N |last2=Parker |first2=L |last3=Brown |first3=P |last4=Dummer |first4=TJ |title=Arsenic in drinking water and urinary tract cancers: a systematic review of 30 years of epidemiological evidence. |journal=Environmental Health |date=2 June 2014 |volume=13 |pages=44 |doi=10.1186/1476-069X-13-44 |pmid=24889821|pmc=4088919 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Clin |first1=B |last2="RecoCancerProf" Working |first2=Group. |last3=Pairon |first3=JC |title=Medical follow-up for workers exposed to bladder carcinogens: the French evidence-based and pragmatic statement. |journal=BMC Public Health |date=6 November 2014 |volume=14 |pages=1155 |doi=10.1186/1471-2458-14-1155 |pmid=25377503|pmc=4230399 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Humans |first1=IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to |title=CHLORNAPHAZINE |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304335/ |publisher=International Agency for Research on Cancer |language=en |date=2012}}</ref> Occupations at risk are bus drivers, rubber workers, painters, motor mechanics, leather (including shoe) workers, blacksmiths, machine setters, and mechanics.<ref>{{Cite journal|vauthors=Reulen RC, Zeegers MP |title=A meta-analysis on the association between bladder cancer and occupation |journal=Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. Supplementum |volume= 42|issue=218 |pages=64–78 |date=September 2008 |pmid=18815919 |doi=10.1080/03008880802325192}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Guha |first1=N |last2=Steenland |first2=NK |last3=Merletti |first3=F |last4=Altieri |first4=A |last5=Cogliano |first5=V |last6=Straif |first6=K |title=Bladder cancer risk in painters: a meta-analysis. |journal=Occupational and Environmental Medicine |date=August 2010 |volume=67 |issue=8 |pages=568–73 |doi=10.1136/oem.2009.051565 |pmid=20647380}}</ref> Hairdressers are thought to be at risk as well because of their frequent exposure to permanent hair dyes.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Harling |first1=M |last2=Schablon |first2=A |last3=Schedlbauer |first3=G |last4=Dulon |first4=M |last5=Nienhaus |first5=A |title=Bladder cancer among hairdressers: a meta-analysis. |journal=Occupational and Environmental Medicine |date=May 2010 |volume=67 |issue=5 |pages=351–8 |doi=10.1136/oem.2009.050195 |pmid=20447989|pmc=2981018 }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:29, 21 November 2019

| Bladder cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. The white in the bladder is contrast. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Blood in the urine, pain with urination[1] |

| Usual onset | 65 to 84 years old[2] |

| Types | Transitional cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma[3] |

| Risk factors | Smoking, family history, prior radiation therapy, frequent bladder infections, certain chemicals[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Cystoscopy with tissue biopsies[4] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rates ~77% (US)[2] |

| Frequency | 549,000 new cases (2018)[5] |

| Deaths | 200,000 (2018)[5] |

Bladder cancer is any of several types of cancer arising from the tissues of the urinary bladder.[1] It is a disease in which cells grow abnormally and have the potential to spread to other parts of the body.[6][7] Symptoms include blood in the urine, pain with urination, and low back pain.[1]

Risk factors for bladder cancer include smoking, family history, prior radiation therapy, frequent bladder infections, and exposure to certain chemicals.[1] The most common type is transitional cell carcinoma.[3] Other types include squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.[3] Diagnosis is typically by cystoscopy with tissue biopsies.[4] Staging of the cancer is determined by transurethral resection and medical imaging.[1][8][9]

Treatment depends on the stage of the cancer.[1] It may include some combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy.[1] Surgical options may include transurethral resection, partial or complete removal of the bladder, or urinary diversion.[1] The typical five-year survival rates in the United States is 77%, Canada is 75%, and Europe is 68%.[2][10][11]

Bladder cancer, as of 2018, affected about 1.6 million people globally with 549,000 new cases and 200,000 deaths.[5] Age of onset is most often between 65 and 84 years of age.[2] Males are more often affected than females.[2] In 2018, the highest rate of bladder cancer occurred in Southern and Western Europe followed by North America with rates of 15, 13, and 12 cases per 100,000 people.[5] The highest rates of bladder cancer deaths were seen in Northern Africa and Western Asia followed by Southern Europe.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Bladder cancer characteristically causes blood in the urine (hematuria), which may be visible (gross/macroscopic hematuria) or detectable only by microscope (microscopic hematuria). Blood in the urine is the most common symptom in bladder cancer, and is painless. Visible blood in the urine may be of only short duration, and a urine test may be required to confirm non visible blood. Between 80–90% of people with bladder cancer initially presented with visible blood.[12] Blood in the urine may also be caused by other conditions, such as bladder or ureteric stones, infection, kidney disease, kidney cancers or vascular malformations, though these conditions (except kidney cancers) would typically be painful.

Other possible symptoms include pain during urination (dysuria), frequent urination, or feeling the need to urinate without being able to do so. These signs and symptoms are not specific to bladder cancer, and may also be caused by non-cancerous conditions, including prostate infections, overactive bladder or cystitis.

Patients with advanced disease refer pelvic or bony pain, lower-extremity swelling, or flank pain. Rarely, a palpable mass can be detected on physical examination.

Causes

Tobacco smoking is the main known contributor to urinary bladder cancer; in most populations, smoking is associated with over half of bladder cancer cases in men and one-third of cases among women,[13] however these proportions have reduced over recent years since there are fewer smokers in Europe and North America.[14] There is an almost linear relationship between smoking duration (in years), pack years and bladder cancer risk. A risk plateau at smoking about 15 cigarettes a day can be observed (meaning that those who smoke 15 cigarettes a day are approximately at the same risk as those smoking 30 cigarettes a day). Quitting smoking reduces the risk, however former smokers will most likely always be at a higher risk of bladder cancer compared to people who have never smoked.[14] Passive smoking also appear to be a risk.[15][16]

Thirty percent of bladder tumors probably result from occupational exposure in the workplace to carcinogens such as benzidine. 2-Naphthylamine, which is found in cigarette smoke, has also been shown to increase bladder cancer risk. Occupational or circumstantial exposure to the following substances has also been implicated as a cause of bladder cancer; 4-aminobiphenyl (rubber industry), β-naphtylamine (rubber industry), phenacetin (analgesic), arsenic in drinking water, auramine (dye manufacturing), magenta (dye manufacturing), ortho-toluidine (dye manufacturing), epoxy and polyurethane resin hardening agents (plastics industry), chlornaphazine, coal-tar pitch.[17][18][19][20] Occupations at risk are bus drivers, rubber workers, painters, motor mechanics, leather (including shoe) workers, blacksmiths, machine setters, and mechanics.[21][22] Hairdressers are thought to be at risk as well because of their frequent exposure to permanent hair dyes.[23]

Infection with Schistosoma haematobium (bilharzia or schistosomiasis) may cause bladder cancer, specially of the squamous cell type.[24] Schistosoma eggs induces a chronic inflammatory state in the bladder wall resulting in tissue fibrosis.[25] Higher levels of N-nitroso compounds(nitrate) has been detected in urine samples of people with schistosomiasis.[26] N-Nitroso compounds have been implicated in the pathogenesis of schistosomiasis related bladder cancer. They are known to cause alkylation DNA damage, specially Guanine to Adenine transition mutations in the H-ras and p53 tumor suppressor gene.[27] Mutations of p53 are detected in 73% of the tumors, BCL-2 mutations accounting for 32% and the combination of the two accounting for 13%.[28] Other causes of squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder include chronic catheterizations in people with a spinal cord injury.[29]

In addition to these major risk factors there are also numerous other modifiable factors that are less strongly (i.e. 10–20% risk increase) associated with bladder cancer, for example, obesity.[30] Although these could be considered as minor effects, risk reduction in the general population could still be achieved by reducing the prevalence of a number of smaller risk factor together.[31]

It has been suggested that mutations at HRAS,PIK3CA, TERT, KRAS2, RB1, TSC1 and FGFR3 may be associated in some cases.[32][33] Deletions of parts or whole of chromosome 9 is common in bladder cancer.[34] Low grade cancer are known to harbor mutations in RAS pathway (15%) and the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene (60%), both of which play a role in MAPK pathway. p53 and RB gene mutations are implicated in high-grade muscle invasive tumors.[35] 89% of muscle invasive cancers have shown mutations in chromatin-remodelling and histone modifying genes.[36] Deletion of both copies of the GSTM1 gene has a modest increase in risk of bladder cancer. GSTM1 gene product glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) participates in the detoxification process of carcinogens such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons found in cigarette smoke.[37] Similarly, mutations in NAT2 (n-acetyltransferase) is associated with increased risk for bladder cancer. N-acetyltransferase helps in detoxification of carcinogens such as aromatic amines (also present in cigarette smoke).[38]

Diagnosis

Currently, the best diagnosis of the state of the bladder is by way of cystoscopy, which is a procedure in which a flexible or rigid tube (called a cystoscope) bearing a camera and various instruments is introduced into the bladder through the urethra. The flexible procedure allows for a visual inspection of the bladder, for minor remedial work to be undertaken and for samples of suspicious lesions to be taken for a biopsy. A rigid cystoscope is used under general anesthesia in the operating room and can support remedial work and biopsies as well as more extensive tumor removal. Unlike papillary lesion, which grow into the bladder cavity and are readily visible, carcinoma in situ lesion are flat and obscure. Detection of carcinoma in situ lesions requires multiple biopsies from different areas of interior bladder wall.[39] Photodynamic detection (blue light cystoscopy) can aid in the detection of carcinoma in situ. In photodynamic detection, a dye is instilled into the bladder with the help of a catheter. Cancer cells take up this dye and are visible under blue light, providing visual clues on areas to biopsied or resected.[40]

Urine cytology can be obtained in voided urine or at the time of the cystoscopy ("bladder washing"). Cytology is not very sensitive for low-grade or grade 1 tumors (a negative result cannot reliably exclude bladder cancer) but has a high specificity (a positive result reliably detects bladder cancer).[41] There are newer non-invasive urine bound markers available as aids in the diagnosis of bladder cancer, including human complement factor H-related protein, high-molecular-weight carcinoembryonic antigen, and nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP22).[42] NMP22 is also available as a prescription home test. Other non-invasive urine based tests include the CertNDx Bladder Cancer Assay, which combines FGFR3 mutation detection with protein and DNA methylation markers to detect cancers across stage and grade, UroVysion, and Cxbladder.

However, visual detection in any form listed above, is not sufficient for establishing pathological classification, cell type or the stage of the present tumor. A so-called cold cup biopsy during an ordinary cystoscopy (rigid or flexible) will not be sufficient for pathological staging either. Hence, a visual detection needs to be followed by transurethral surgery. The procedure is called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). Further, bimanual examination should be carried out before and after the TURBT to assess whether there is a palpable mass or if the tumour is fixed ("tethered") to the pelvic wall. The pathological classification and staging information obtained by the TURBT-procedure, is of fundamental importance for making the appropriate choice of ensuing treatment and/or follow-up routines.[43]

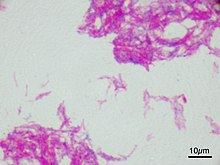

Pathological classification

95% of bladder cancers are transitional cell carcinoma. The other 5% are squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, small cell carcinoma, and secondary deposits from cancers elsewhere in the body.[44] Depending on pattern of growth transitional cell carcinoma can be classified as papillary or non-papillary. Non-papillary carcinoma includes carcinoma in situ (CIS), microinvasive carcinoma and frankly invasive carcinoma.[45]

Transitional cell carcinoma can undergo divergent differentiation (25%) into its variants.[45][46][47] Histologically, papillary transitional cell carcinoma can present in its typical form or with divergent differentiation (squamous, glandular differentiation or micropapillary variant). Divergent histologies of non-papillary transitional cell carcinoma are listed below.

| Variant | Histology | Percentage of cases | Implications[48] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Squamous differentiation | Presence of intercellular bridges or keratinization | 60% | Outcomes similar to conventional transitional cell carcinoma |

| Glandular differentiation | Presence of true glandular spaces | 10% | |

| Sarcomatoid foci | Presence of both epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation | 7% | Clinically aggressive[49] |

| Micropapillary variant | Resembles papillary serous carcinoma of the ovary or resembling micropapillary carcinoma of breast or lung[50] | 3.7% | Clinically aggressive, early cystectomy recommended |

| Urothelial carcinoma with small tubules and microcystic form | Presence of cysts with a size range of microscopic to 1-2mm | Rare | |

| Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma | Resembles lymphoepithelioma of the nasopharynx | ||

| Lymphoma-like and plasmacytoid variants | Malignant cells resemble cells of malignant lymphoma or plasmacytoma | ||

| Nested variant | Histologically look similar to von Brunn’s nests | Can be misdiagnosed as benign von brunn’s nests or non-invasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma | |

| Urothelial carcinoma with giant cells | Presence of epithelial tumour giant cells and looks similar to giant cell carcinoma of the lung | ||

| Trophoblastic differentiation | Presence of syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells or choriocarcinomatous differentiation, may express HCG | ||

| Clear cell variant | Clear cell pattern with glycogen-rich cytoplasm | ||

| Plasmacytoid | Cells with abundant lipid content, mimic signet ring cell adenocarcinoma of stomach/ lobular breast cancer | Clinically aggressive, propensity for peritoneal spread | |

| Unusual stromal reactions | Presence of following; pseudosarcomatous stroma, stromal osseous or cartilaginous metaplasia, osteoclast-type giant cells, lymphoid infiltrate |

Carcinoma in situ (CIS) invariably consists of cytologically high-grade tumour cells.[51]

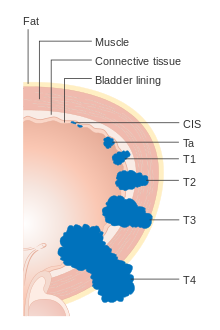

Staging

Bladder cancer is staged (classified by the extent of spread of the cancer) and graded (how abnormal and aggressive the cells appear under the microscope) to determine treatments and estimate outcomes. Staging usually follows the first transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). If invasive or high grade (includes carcinoma in situ) cancer is detected, a CT scan (abdomen and pelvis or urogram) and CT chest or x-ray chest should be conducted for disease staging. Increase in alkaline phosphatase levels without evidence of liver disease should be evaluated for bone metastasis by a bone scan.[52] Papillary tumors confined to the mucosa or which invade the lamina propria are classified as Ta or T1. Flat lesion are classified as Tis. Both are grouped together as non-muscle invasive disease for therapeutic purposes.

In the TNM staging system (8th Edn. 2017) for bladder cancer:[53][54]

T (Primary tumour)

- TX Primary tumour cannot be assessed

- T0 No evidence of primary tumour

- Ta Non-invasive papillary carcinoma

- Tis Carcinoma in situ ('flat tumour')

- T1 Tumour invades subepithelial connective tissue

- T2a Tumour invades superficial muscle (inner half)

- T2b Tumour invades deep muscle (outer half)

- T3 Tumour invades perivesical tissue:

- T3a Microscopically

- T3b Macroscopically (extravesical mass)

- T4a Tumour invades prostate, uterus or vagina

- T4b Tumour invades pelvic wall or abdominal wall

N (Lymph nodes)

- NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0 No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1 Metastasis in a single lymph node in true pelvis (hypogastric, obturator, external iliac, or presacral nodes)

- N2 Metastasis in multiple lymph nodes in true pelvis (hypogastric, obturator, external iliac, or presacral nodes)

- N3 Metastasis in common iliac lymph node(s)

M (Distant metastasis)

- MX Distant metastasis cannot be assessed

- M0 No distant metastasis

- M1 Distant metastasis.

- M1a: The cancer has spread only to lymph nodes outside of the pelvis.

- M1b: The cancer has spread other parts of the body.

The most common sites for bladder cancer metastases are the lymph nodes, bones, lung, liver, and peritoneum.[55]

Numerical

The stages above can be integrated into a numerical staging (with Roman numerals) as follows:[56]

| Stage | Tumor | Nodes | Metastasis | 5-year survival in the US[57] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0a | Ta | N0 | M0 | 98% |

| Stage 0is | Tis | N0 | M0 | 95% |

| Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 | 63% |

| Stage II | T2a | N0 | M0 | |

| T2b | ||||

| Stage IIIA | T3a | N0 | M0 | 35% |

| T3b | ||||

| T4a | ||||

| T1-4a | N1 | |||

| Stage IIIB | T1-4a | N2 | M0 | |

| N3 | ||||

| Stage IVA | T4b | Any N | M0 | |

| Any T | M1a | |||

| Stage IVB | Any T | ny N | M1b | 5% |

Grading

According to WHO classification (1973) bladder cancers are histologically graded into:[58]

- G1 – Well differentiated,

- G2 – Moderately differentiated

- G3 – Poorly differentiated

WHO classification (2004)[59][60]

- Papillary lesions

- Urothelial Papilloma

- Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP)

- Low Grade

- High Grade

- Flat lesions

- Urothelial proliferation of uncertain malignant potential

- Reactive atypia

- Atypia of unknown significance

- Urothelial dysplasia

- Urothelial CIS (always high grade)

- Primary

- Secondary

- Concurrent

Risk stratification

People are risk-stratified based on clinical and pathological factors so that they are treated appropriately depending on their probability of having progression and/or recurrence.[61] People with non-muscle invasive tumors are categorized into low-risk, intermediate-risk and high-risk or provided with a numerical risk score. Risk-stratification framework is provided by American Urology Association/Society of Urological Oncology (AUA/SUO stratification), European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk tables and Club Urológico Español de Tratamiento Oncológico (CUETO) scoring model.[62][63][64]

| Low risk | Intermediate risk | High risk |

|---|---|---|

| Low grade solitary Ta tumor, smaller than 3 cm | Recurrence within 1 year, Low grade Ta tumor | High grade T1 |

| Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential | Solitary low grade Ta tumor, bigger than 3 cm | Any recurrent tumor Or any hight grade Ta |

| Low grade Ta, multifocal tumors | High grade Ta, bigger than 3 cm (or multifocal) | |

| High grade Ta, smaller than 3 cm | Any carcinoma in situ | |

| Low grade T1 | Any BCG failure in High grade patient | |

| Any variant histology | ||

| Any lymphovascular invasion | ||

| Any High grade prostatic urethral involvement |

The EORTC and CUETO model use a cumulative score obtained from individual prognostic factors, which are then converted into risk of progression and recurrence. The six prognostic factors included in the EORTC model are number of tumors, recurrence rate, T-stage, presence of carcinoma-in-situ and grade of the tumor.Scoring for recurrence in the CUETO model incorporates 6 variables; age, gender, grade, tumor status, number of tumors and presence of tis. For progression scoring the previous 6 variables plus T stage is used.[65][66]

| Model | Cumulative score for recurrence | Recurrence at 1-year (%) | Recurrence at 5-year (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC | 0 | 15 | 31 |

| 1-4 | 24 | 46 | |

| 5-9 | 38 | 62 | |

| 10-17 | 61 | 78 | |

| CUETO | 0-4 | 8.2 | 21 |

| 5-6 | 12 | 36 | |

| 7-9 | 25 | 48 | |

| 10-16 | 42 | 68 |

| Model | Cumulative score for progression | Progression at 1-year (%) | Progression at 5-year (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC | 0 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| 2-6 | 1 | 6 | |

| 7-13 | 5 | 17 | |

| 12-23 | 17 | 45 | |

| CUETO | 0-4 | 1.2 | 3.7 |

| 5-6 | 3 | 12 | |

| 7-9 | 5.5 | 21 | |

| 10-16 | 14 | 34 |

Molecular classification

There are efforts to classify bladder cancer into different molecular subtypes. The variability of the disease is due to differences in cancer cell related pathways, as well as due to varying components of the tumor microenvironment, such as infiltrating immune cells that affect the prognosis after therapy. This classification is not used as a standard of care, but has generated information on subgroup molecular characteristics that can be used in the future for stratified or personalized therapies.[69]

Prevention

As of 2015, there is limited high level evidence to suggest that eating vegetable and fruits decreases the risk of bladder cancer.[38] A 2008 study concluded that "specific fruit and vegetables may act to reduce the risk of bladder cancer."[70] Fruit and yellow-orange vegetables, particularly carrots and those containing selenium,[71] are probably associated with a moderately reduced risk of bladder cancer. Citrus fruits and cruciferous vegetables were also identified as having a possibly protective effect. However an analysis of 47,909 men in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study showed little relation between cancer reduction and high consumption of fruits and vegetables overall, or yellow or green leafy vegetables specifically, compared to the reduction seen among those men who consumed large amounts of cruciferous vegetables.

While it is suggested that the polyphenol compounds in tea may have an inhibitory effect on bladder tumor formation and growth, there is limited evidence to suggesting drinking tea decreases bladder cancer risk.[38]

In a 10-year study involving almost 49,000 men, researchers found that men who drank at least 1,44 L of water (around 6 cups) per day had a significantly reduced incidence of bladder cancer when compared with men who drank less. It was also found that: "the risk of bladder cancer decreased by 7% for every 240 mL of fluid added".[72] The authors proposed that bladder cancer might partly be caused by the bladder directly contacting carcinogens that are excreted in urine, although this has not yet been confirmed in other studies.[70]

Screening

As of 2019 there is insufficient evidence to determine if screening for bladder cancer in people without symptoms is effective or not.[73]

Treatment

The treatment of bladder cancer depends on how deeply the tumor invades into the bladder wall.

Treatment strategies for bladder cancer include:[74]

- Non-muscle invasive: transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) with or without intavesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy

- Muscle invasive: radical cystectomy plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy (multimodal therapy) or transurethral resection with chemoradiation (trimodal therapy)

- Metastatic disease: cisplatin-based chemotherapy

- Metastatic disease with contraindication for chemotherapy: checkpoint inhibitors

- Squamous cell carcinoma of bladder: radical cystectomy

Non-muscle invasive

Transurethral resection

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (those not entering the muscle layer of the bladder) can be "shaved off" using an electrocautery device attached to a cystoscope, which in that case is called a resectoscope. The procedure is called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) and serves primarily for pathological staging. In case of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer the TURBT is in itself the treatment, but in case of muscle invasive cancer, the procedure is insufficient for final treatment.[43] Additionally, blue light cystoscopy with optical-imaging agent Hexaminolevulinate (HAL) is recommended at initial TURBT to increase lesion detection and improve resection quality thereby reducing recurrence.[75][76] It is important to assess the quality of the resection, if there is evidence of incomplete resection or there is no muscle in the specimen (without which muscle invasiveness cannot be determined) a second TURBT is strongly recommended.[77] At this point classifying people into risk groups is recommended. For low risk tumors the first surveillance cystoscopy should be carried out within 3 to 4 weeks of initial treatment to determine recurrence of cancer.[78] if negative, a second cystoscopy is carried out at 12 months and then yearly for 5-years.[43]

Chemotherapy

A single instillation of chemotherapy into the bladder after primary TURBT has shown benefit in deceasing recurrence. Medications which can used for this purpose are mitomycin C (MMC), epirubicin, pirarubicin and gemcitabine. Instillation of post-operative chemotherapy should be conducted within first few hours after TURBT. As time progress residual tumor cells are known to adhere firmly and are covered by extracellular matrix which decrease the efficacy of the instillation.[77] If there is a suspicion of bladder perforation during TURBT, chemotherapy should not be instilled into the bladder. Studies have shown that efficacy of chemotherapy is increased by the use of Device assisted chemotherapy .[79] These technologies use different mechanisms to facilitate the absorption and action of a chemotherapy drug instilled directly into the bladder. Another technology – electromotive drug administration (EMDA) – uses an electric current to enhance drug absorption after surgical removal of the tumor.[80][81] Another technology, thermotherapy, uses radio-frequency energy to directly heat the bladder wall, which together with chemotherapy shows a synergistic effect, enhancing each other's capacity to kill tumor cells. This technology has been studied by a number of different investigators.[82][83][84][85]

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy by Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) delivery into the bladder is also used to treat and prevent the recurrence of NMIBC.[86] BCG is a vaccine against tuberculosis that is prepared from attenuated (weakened) live bovine tuberculosis bacillus, Mycobacterium bovis, that has lost its virulence in humans. BCG immunotherapy is effective in up to 2/3 of the cases at this stage, and in randomized trials has been shown to be superior to standard chemotherapy.[87] The exact mechanism by which BCG prevents recurrence is unknown. However, it has been shown that the bacteria are taken up the cancer cells.[88] The infection of these cells in the bladder may trigger a localized immune reaction which clears residual cancer cells.[89][90]

People whose tumors recurred after treatment with BCG are more difficult to treat.[91] Many physicians recommend cystectomy for these patients. This recommendation is in accordance with the official guidelines of the European Association of Urologists (EAU)[92] and the American Urological Association (AUA)[93]

| Risk | Other considerations | Chemotherapy | Immunotherapy (BCG) | Cytoscopy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | - | - | - | at 3-months followed by cystoscopy at 12-months, then yearly for 5-years |

| Intermediate (primary or recurrent tumors) | No previous chemotherapy | Intravesical chemotherapy for 1 year OR Intravesical BCG for 1 year | at 3-months followed by once every 3–6 months for 5-years and then yearly. | |

| Previous chemotherapy | - | Intravesical BCG for 1 year | ||

| High | - | - | Intravesical BCG for 3 year (as tolerated) | at 3-months with cytology followed by once every 3-months for 2-years after that, 6 monthly for 5 years then yearly. |

| T1G3/High grade, Lymphovascular invasion, presence of variant histology | Consider radical cystectomy | |||

Muscle invasive

Multimodal therapy

Untreated, superficial tumors may gradually begin to infiltrate the muscular wall of the bladder (muscle invasive bladder cancer). Tumors that infiltrate the bladder wall require more radical surgery, where part (partial cystectomy) or all (radical cystectomy) of the bladder is removed (a cystectomy) and the urinary stream is diverted into an isolated bowel loop (called an ileal conduit or urostomy). In some cases, skilled surgeons can create a substitute bladder (a neobladder) from a segment of intestinal tissue, but this largely depends upon patient preference, age of patient, renal function, and the site of the disease. Even after surgical removal of bladder, 50% of the people with muscle invasive disease (T2-T4) develop metastatic disease within two years due to micrometastasis,.[94] In such, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (chemotherapy before main treatment, ie surgery) has shown to increase overall survival at 5 years from 45% to 50% with a absolute survival benefit of 5%.[95][96][97] Currently the two most used chemotherapy regimens for neoadjuvant chemotherapy are platinum based; methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, with cisplatin (MVAC) and gemcitabine with cisplatin/carboplatin (GC).[98] Although, optimal regime has not been established, the preferred regime for neoadjuvant therapy is MVAC.[98]

Trimodal therapy

In patients with T2N0M0 tumors, a combination of radiation and chemotherapy (chemoradiation) in conjunction with transurethral (endoscopic) bladder tumor resection can be used as an alternative.[99] Review of available large data series on this so-called trimodality therapy has indicated similar long-term cancer specific survival rates, with improved overall quality of life as for patients undergoing radical cystectomy with urinary reconstruction. However, currently no randomized control trials are available which has compared trimodal therapy with radical cystectomy. These patients are usually highly selected and do not have multi-focal disease or carcinoma in-situ, which is associated with a higher rate of recurrence, progression, and death from bladder cancer versus patients who undergo radical cystectomy.[100]

In patient who have elected to undergo trimodel therapy, a maximal TURBT is conducted followed by chemoradiation therapy. Radiation sensitizing chemotherapy regimens consisting of cisplatin or 5-flurouracil and mitomycin C are used. Radiation therapy is via external bean radiotherapy (EBRT) with a target curative dose of 64-66 Gy.[101] Surveillance for progression or recurrence should conducted with the aid of CT scans, cystoscopies and urine cytology.[102]

In patients who fail trimodal therapy, radical cystectomy should be considered if there is muscle invasive disease or recurrent tumors. TURBT with intravesical therapy is indicated after treatment failure for non-muscle invasive disease.[102]

Metastatic disease

Cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy is the standard of care for metastatic bladder care.[103]Again, two most used chemotherapy regimens for chemotherapy in metastatic bladder cancer are platinum based; methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, with cisplatin (MVAC) and gemcitabine with cisplatin/carboplatin (GC). Paclitaxel can be added with gemcitabine and cisplatin (PCG regimen; triple therapy) as an alternative treatment. MVAC is better tolerated if it is combined with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. This combination has shown to decease all cause mortality.[104]

Bladder cancer that is refractory or shows progression after platinum based chemotherapy can be treated with Vinflunine, a third generation vinca alkaloid (approved in Europe).[105]

Prognosis

People with superficial tumors, also known as non-muscle invasive tumors, have a favorable outcome (5-year survival is 95% vs. 69% of muscle invasive bladder cancer).[106][107] However, 70% of them will have a recurrence after initial treatment with 30% of them presenting with muscle invasive disease.[108] Recurrence and progression to a higher disease stage have a less favorable outcome.[109]

Epidemiology

| Rank | Country | Overall | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lebanon | 25 | 40 | 9 |

| 2 | Greece | 21 | 40 | 4 |

| 3 | Denmark | 18 | 29 | 8 |

| 4 | Hungary | 17 | 27 | 9 |

| 5 | Albania | 16 | 27 | 6 |

| 5 | Netherlands | 16 | 26 | 8 |

| 7 | Belgium | 16 | 27 | 6 |

| 8 | Italy | 15 | 27 | 6 |

| 9 | Germany | 15 | 26 | 6 |

| 10 | Spain | 15 | 27 | 6 |

Globally, in 2017, bladder cancer resulted in 196,000 deaths, a 5.4% (age adjusted) decrease from 2007.[113] In 2018, the age adjusted rates of new cases of bladder cancer was 6 cases per 100,000 people and age adjusted death rate was 2 deaths per 100,000 people. Lebanon and Greece have the highest rate of new cases. In Lebanon, this high risk is attributed to high number of smokers and petrochemical air pollution.[114] Risk of bladder cancer occurrence is 4 times higher in men than women.[5] Smoking can only partially explain this higher rates in men in western hemisphere.[115] One other reason is that the androgen receptor, which is much more active in men than in women, may play a part in the development of the cancer.[116] In Africa, men are more prone to do field work and are exposed to infection with Schistosoma, this may explain to a certain extent the gap in incidence.[115] However, women present with more aggressive disease and have worse outcomes than men. This difference in outcomes is attributed to numerous factors such as, difference in carcinogen exposure, genetics, social and quality of care.[117]

Canada

Bladder cancer is 6th most common cancer accounting for 3.7% of the new cancer cases. In 2018, 9160 new cases were diagnosed and 2467 died from it.[118]

China

Bladder cancer is 14th most common cancer and 16th most common cause of cancer death. In, 2018 it accounted for 82,300 new cases and 38,200 deaths.[119]

UK

Bladder cancer is the ninth most common cancer in the UK accounting for 2.7% of all the new cancers cases. In 2018, there was 12,200 new cases and 6100 people died from it.[120]

US

In the United States in 2019 80,470 cases and 17,670 deaths are expected making it the 6th most common type of cancer in the region.[2] Bladder cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer in men and the ninth most common cancer in women. More than 60,000 men and 16,000 women are diagnosed with bladder cancer each year.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Bladder Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Cancer of the Urinary Bladder - Cancer Stat Facts". SEER. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "Bladder Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Bladder Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bladder Cancer Factsheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Cancer Fact sheet N°297". World Health Organization. February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ "EAU Guidelines: Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer". Uroweb.

- ^ "Bladder Cancer - Stages and Grades". Cancer.Net. 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Bladder cancer". World Cancer Research Fund. 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Survival statistics for bladder cancer - Canadian Cancer Society". www.cancer.ca.

- ^ Avellino, Gabriella J.; Bose, Sanchita; Wang, David S. (1 June 2016). "Diagnosis and Management of Hematuria". Surgical Clinics of North America. 96 (3): 503–515. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2016.02.007. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 27261791.

- ^ Zeegers MP; Tan, FE; Dorant, E; Van Den Brandt, PA (2000). "The impact of characteristics of cigarette smoking on urinary tract cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies". Cancer. 89 (3): 630–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<630::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 10931463.

- ^ a b Osch, Frits H. M. van; Jochems, Sylvia H. J.; Schooten, Frederik-Jan van; Bryan, Richard T.; Zeegers, Maurice P. (20 April 2016). "Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies". International Journal of Epidemiology. 45 (3): 857–870. doi:10.1093/ije/dyw044. ISSN 0300-5771. PMID 27097748.

- ^ Yan, H; Ying, Y; Xie, H; Li, J; Wang, X; He, L; Jin, K; Tang, J; Xu, X; Zheng, X (2018). "Secondhand smoking increases bladder cancer risk in nonsmoking population: a meta-analysis". Cancer management and research. 10: 3781–3791. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S175062. PMID 30288109.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Health Risks of Secondhand Smoke". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Humans, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to (2012). 4-AMINOBIPHENYL. International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- ^ Saint-Jacques, N; Parker, L; Brown, P; Dummer, TJ (2 June 2014). "Arsenic in drinking water and urinary tract cancers: a systematic review of 30 years of epidemiological evidence". Environmental Health. 13: 44. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-13-44. PMC 4088919. PMID 24889821.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Clin, B; "RecoCancerProf" Working, Group.; Pairon, JC (6 November 2014). "Medical follow-up for workers exposed to bladder carcinogens: the French evidence-based and pragmatic statement". BMC Public Health. 14: 1155. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1155. PMC 4230399. PMID 25377503.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Humans, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to (2012). CHLORNAPHAZINE. International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- ^ Reulen RC, Zeegers MP (September 2008). "A meta-analysis on the association between bladder cancer and occupation". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. Supplementum. 42 (218): 64–78. doi:10.1080/03008880802325192. PMID 18815919.

- ^ Guha, N; Steenland, NK; Merletti, F; Altieri, A; Cogliano, V; Straif, K (August 2010). "Bladder cancer risk in painters: a meta-analysis". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 67 (8): 568–73. doi:10.1136/oem.2009.051565. PMID 20647380.

- ^ Harling, M; Schablon, A; Schedlbauer, G; Dulon, M; Nienhaus, A (May 2010). "Bladder cancer among hairdressers: a meta-analysis". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 67 (5): 351–8. doi:10.1136/oem.2009.050195. PMC 2981018. PMID 20447989.

- ^ Mostafa, MH; Sheweita, SA; O'Connor, PJ (January 1999). "Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 12 (1): 97–111. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.97. PMC 88908. PMID 9880476.

- ^ Zaghloul, Mohamed S. (December 2012). "Bladder cancer and schistosomiasis". Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute. 24 (4): 151–159. doi:10.1016/j.jnci.2012.08.002. PMID 23159285.

- ^ Mostafa, MH; Helmi, S; Badawi, AF; Tricker, AR; Spiegelhalder, B; Preussmann, R (April 1994). "Nitrate, nitrite and volatile N-nitroso compounds in the urine of Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni infected patients". Carcinogenesis. 15 (4): 619–25. doi:10.1093/carcin/15.4.619. PMID 8149471.

- ^ Badawi, AF (2 August 1996). "Molecular and genetic events in schistosomiasis-associated human bladder cancer: role of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes". Cancer Letters. 105 (2): 123–38. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(96)04284-x. PMID 8697435.

- ^ Chaudhary, KS; Lu, QL; Abel, PD; Khandan-Nia, N; Shoma, AM; el Baz, M; Stamp, GW; Lalani, EN (January 1997). "Expression of bcl-2 and p53 oncoproteins in schistosomiasis-associated transitional and squamous cell carcinoma of urinary bladder". British Journal of Urology. 79 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.30717.x. PMID 9043502.

- ^ Shokeir, AA (January 2004). "Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder: pathology, diagnosis and treatment". BJU International. 93 (2): 216–20. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04588.x. PMID 14690486.

- ^ Sun, Jiang-Wei; Zhao, Long-Gang; Yang, Yang; Ma, Xiao; Wang, Ying-Ying; Xiang, Yong-Bing (24 March 2015). "Obesity and Risk of Bladder Cancer: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 15 Cohort Studies". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0119313. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019313S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119313. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4372289. PMID 25803438.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Al-Zalabani, AbdulmohsenH.; Stewart, KellyF.J.; Wesselius, Anke; Schols, AnnemieM.W.J.; Zeegers, MauriceP. (21 March 2016). "Modifiable risk factors for the prevention of bladder cancer: a systematic review of meta-analyses". European Journal of Epidemiology. 31 (9): 811–851. doi:10.1007/s10654-016-0138-6. ISSN 0393-2990. PMC 5010611. PMID 27000312.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 109800

- ^ Zhang, X; Zhang, Y (September 2015). "Bladder Cancer and Genetic Mutations". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 73 (1): 65–9. doi:10.1007/s12013-015-0574-z. PMID 27352265.

- ^ Reference, Genetics Home. "Bladder cancer". Genetics Home Reference.

- ^ Ahmad, I.; Sansom, O. J.; Leung, H. Y. (15 March 2012). "Exploring molecular genetics of bladder cancer: lessons learned from mouse models". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 5 (3): 323–332. doi:10.1242/dmm.008888. PMC 3339826. PMID 22422829.

- ^ Humphrey, PA; Moch, H; Cubilla, AL; Ulbright, TM; Reuter, VE (July 2016). "The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours" (PDF). European Urology. 70 (1): 106–119. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028. PMID 26996659.

- ^ Engel, LS; Taioli, E; Pfeiffer, R; Garcia-Closas, M; Marcus, PM; Lan, Q; Boffetta, P; Vineis, P; Autrup, H; Bell, DA; Branch, RA; Brockmöller, J; Daly, AK; Heckbert, SR; Kalina, I; Kang, D; Katoh, T; Lafuente, A; Lin, HJ; Romkes, M; Taylor, JA; Rothman, N (15 July 2002). "Pooled analysis and meta-analysis of glutathione S-transferase M1 and bladder cancer: a HuGE review". American Journal of Epidemiology. 156 (2): 95–109. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf018. PMID 12117698.

- ^ a b c "Bladder Cancer Report" (PDF). World Cancer Research Fund : International. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "EAU Guidelines: Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Diagnosis". Uroweb. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "EAU Guidelines: Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer diagnosis". Uroweb. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Lotan, Y.; Roehrborn, C. G. (2003). "Sensitivity and specificity of commonly available bladder tumor markers versus cytology: Results of a comprehensive literature review and meta-analyses". Urology. 61 (1): 109–118, discussion 118. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02136-2. PMID 12559279.

- ^ Shariat; Karam, JA; Lotan, Y; Karakiewizc, PI; et al. (2008). "Critical Evaluation of Urinary Markers for Bladder Cancer Detection and Monitoring". Reviews in Urology. 10 (2): 120–135. PMC 2483317. PMID 18660854.

- ^ a b c d "Uroweb - European Association of Urology (EAU)". Uroweb. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "Types of Bladder Cancer: TCC & Other Variants | CTCA". CancerCenter.com. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ a b Amin, Mahul B (29 May 2009). "Histological variants of urothelial carcinoma: diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic implications". Modern Pathology. 22 (S2): S96–S118. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2009.26. PMID 19494856.

- ^ Chalasani, V; Chin, JL; Izawa, JI (December 2009). "Histologic variants of urothelial bladder cancer and nonurothelial histology in bladder cancer". Canadian Urological Association. 3 (6 Suppl 4): S193-8. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1195. PMC 2792446. PMID 20019984.

- ^ Moschini, M; D'Andrea, D; Korn, S; Irmak, Y; Soria, F; Compérat, E; Shariat, SF (November 2017). "Characteristics and clinical significance of histological variants of bladder cancer". Nature Reviews. Urology. 14 (11): 651–668. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2017.125. PMID 28895563.

- ^ Warrick, Joshua I. (5 October 2017). "Clinical Significance of Histologic Variants of Bladder Cancer". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 15 (10): 1268–1274. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2017.7027. PMID 28982751.

- ^ Venyo, AK; Titi, S (2014). "Sarcomatoid variant of urothelial carcinoma (carcinosarcoma, spindle cell carcinoma): a review of the literature". ISRN Urology. 2014: 794563. doi:10.1155/2014/794563. PMC 3920806. PMID 24587922.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Urothelial Carcinoma Variants - American Urological Association". www.auanet.org.

- ^ Tang, DH; Chang, SS (December 2015). "Management of carcinoma in situ of the bladder: best practice and recent developments". Therapeutic Advances in Urology. 7 (6): 351–64. doi:10.1177/1756287215599694. PMC 4647140. PMID 26622320.

- ^ "Bladder Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version". National Cancer Institute. 23 August 2019.

- ^ "EAU Guidelines - STAGING AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS". Uroweb.

- ^ Magers, Martin J; Lopez-Beltran, Antonio; Montironi, Rodolfo; Williamson, Sean R; Kaimakliotis, Hristos Z; Cheng, Liang (January 2019). "Staging of bladder cancer". Histopathology. 74 (1): 112–134. doi:10.1111/his.13734. PMID 30565300.

- ^ Shinagare, Atul B.; Ramaiya, Nikhil H.; Jagannathan, Jyothi P.; Fennessy, Fiona M.; Taplin, Mary-Ellen; Van den Abbeele, Annick D. (2011). "Metastatic Pattern of Bladder Cancer: Correlation With the Characteristics of the Primary Tumor". American Journal of Roentgenology. 196 (1): 117–122. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5036. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 21178055.

- ^ "How is bladder cancer staged?". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 4 October 2015 suggested (help) Last Medical Review: 11/02/2019 - ^ "Survival rates for bladder cancer by stage". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Last Medical Review: 02/26/2014

- ^ Seth P. Lerner. "Overview of Diagnosis and Management of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. ODAC September 14, 2016

- ^ Epstein, JI; Amin, MB; Reuter, VR; Mostofi, FK (December 1998). "The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Bladder Consensus Conference Committee". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 22 (12): 1435–48. doi:10.1097/00000478-199812000-00001. PMID 9850170.

- ^ Compérat, EM; Burger, M; Gontero, P; Mostafid, AH; Palou, J; Rouprêt, M; van Rhijn, BWG; Shariat, SF; Sylvester, RJ; Zigeuner, R; Babjuk, M (May 2019). "Grading of Urothelial Carcinoma and The New "World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs 2016"". European Urology Focus. 5 (3): 457–466. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2018.01.003. PMID 29366854.

- ^ Chang, SS; Boorjian, SA; Chou, R; Clark, PE; Daneshmand, S; Konety, BR; Pruthi, R; Quale, DZ; Ritch, CR; Seigne, JD; Skinner, EC; Smith, ND; McKiernan, JM (October 2016). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline". The Journal of Urology. 196 (4): 1021–9. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.049. PMID 27317986.

- ^ a b "Bladder Cancer: Non-Muscle Invasive Guideline - American Urological Association". www.auanet.org.

- ^ Soukup, V; Čapoun, O; Cohen, D; Hernández, V; Burger, M; Compérat, E; Gontero, P; Lam, T; Mostafid, AH; Palou, J; van Rhijn, BWG; Rouprêt, M; Shariat, SF; Sylvester, R; Yuan, Y; Zigeuner, R; Babjuk, M (20 November 2018). "Risk Stratification Tools and Prognostic Models in Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Critical Assessment from the European Association of Urology Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel". European Urology Focus. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2018.11.005. PMID 30470647.

- ^ Sylvester, Richard J.; van der Meijden, Adrian P.M.; Oosterlinck, Willem; Witjes, J. Alfred; Bouffioux, Christian; Denis, Louis; Newling, Donald W.W.; Kurth, Karlheinz (March 2006). "Predicting Recurrence and Progression in Individual Patients with Stage Ta T1 Bladder Cancer Using EORTC Risk Tables: A Combined Analysis of 2596 Patients from Seven EORTC Trials". European Urology. 49 (3): 466–477. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. PMID 16442208.

- ^ Sylvester, RJ; van der Meijden, AP; Oosterlinck, W; Witjes, JA; Bouffioux, C; Denis, L; Newling, DW; Kurth, K (March 2006). "Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials". European Urology. 49 (3): 466–5, discussion 475–7. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. PMID 16442208.

- ^ Fernandez-Gomez, J; Madero, R; Solsona, E; Unda, M; Martinez-Piñeiro, L; Gonzalez, M; Portillo, J; Ojea, A; Pertusa, C; Rodriguez-Molina, J; Camacho, JE; Rabadan, M; Astobieta, A; Montesinos, M; Isorna, S; Muntañola, P; Gimeno, A; Blas, M; Martinez-Piñeiro, JA (November 2009). "Predicting nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer recurrence and progression in patients treated with bacillus Calmette-Guerin: the CUETO scoring model". The Journal of Urology. 182 (5): 2195–203. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.016. PMID 19758621.

- ^ "EAU Guidelines: Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer". Uroweb.

- ^ Choi, Se Young; Ryu, Jae Hyung; Chang, In Ho; Kim, Tae-Hyoung; Myung, Soon Chul; Moon, Young Tae; Kim, Kyung Do; Kim, Jin Wook (2014). "Predicting Recurrence and Progression of Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer in Korean Patients: A Comparison of the EORTC and CUETO Models". Korean Journal of Urology. 55 (10): 643–9. doi:10.4111/kju.2014.55.10.643. PMC 4198762. PMID 25324946.

- ^ Kamoun, Aurélie; de Reyniès, Aurélien; Allory, Yves; Sjödahl, Gottfrid; Robertson, A. Gordon; Seiler, Roland; Hoadley, Katherine A.; Groeneveld, Clarice S.; Al-Ahmadie, Hikmat; Choi, Woonyoung; Castro, Mauro A.A.; Fontugne, Jacqueline; Eriksson, Pontus; Mo, Qianxing; Kardos, Jordan; Zlotta, Alexandre; Hartmann, Arndt; Dinney, Colin P.; Bellmunt, Joaquim; Powles, Thomas; Malats, Núria; Chan, Keith S.; Kim, William Y.; McConkey, David J.; Black, Peter C.; Dyrskjøt, Lars; Höglund, Mattias; Lerner, Seth P.; Real, Francisco X.; Radvanyi, François (September 2019). "A Consensus Molecular Classification of Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer". European Urology. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.09.006. PMID 31563503.

- ^ a b Brinkman M, Zeegers MP (September 2008). "Nutrition, total fluid and bladder cancer". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. Supplementum. 42 (218): 25–36. doi:10.1080/03008880802285073. PMID 18815914.

- ^ Brinkman M, Zeegers MP (2006). "Use of selenium in chemoprevention of bladder cancer". Lancet Oncol. 7 (9): 766–74. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70862-2. PMID 16945772.

- ^ Valtin H (November 2002). ""Drink at least eight glasses of water a day." Really? Is there scientific evidence for "8 × 8"?". American Journal of Physiology. 283 (5): R993–R1004. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00365.2002. PMID 12376390.

- ^ "Final Update Summary: Bladder Cancer in Adults: Screening - US Preventive Services Task Force". www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ Kamat, Ashish M; Hahn, Noah M; Efstathiou, Jason A; Lerner, Seth P; Malmström, Per-Uno; Choi, Woonyoung; Guo, Charles C; Lotan, Yair; Kassouf, Wassim (December 2016). "Bladder cancer". The Lancet. 388 (10061): 2796–2810. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30512-8. PMID 27345655.

- ^ Witjes, JA; Babjuk, M; Gontero, P; Jacqmin, D; Karl, A; Kruck, S; Mariappan, P; Palou Redorta, J; Stenzl, A; van Velthoven, R; Zaak, D (November 2014). "Clinical and cost effectiveness of hexaminolevulinate-guided blue-light cystoscopy: evidence review and updated expert recommendations". European Urology. 66 (5): 863–71. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.037. PMID 25001887.

- ^ Daneshmand, S; Schuckman, AK; Bochner, BH; Cookson, MS; Downs, TM; Gomella, LG; Grossman, HB; Kamat, AM; Konety, BR; Lee, CT; Pohar, KS; Pruthi, RS; Resnick, MJ; Smith, ND; Witjes, JA; Schoenberg, MP; Steinberg, GD (October 2014). "Hexaminolevulinate blue-light cystoscopy in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: review of the clinical evidence and consensus statement on appropriate use in the USA". Nature Reviews. Urology. 11 (10): 589–96. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2014.245. PMID 25245244.

- ^ a b "EAU Guidelines: Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer". Uroweb.

- ^ Chang, Sam S.; Boorjian, Stephen A.; Chou, Roger; Clark, Peter E.; Daneshmand, Siamak; Konety, Badrinath R.; Pruthi, Raj; Quale, Diane Z.; Ritch, Chad R.; Seigne, John D.; Skinner, Eila Curlee; Smith, Norm D.; McKiernan, James M. (October 2016). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline". Journal of Urology. 196 (4): 1021–1029. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.049. PMID 27317986.

- ^ Witjes JA, Hendricksen K (January 2008). "Intravesical pharmacotherapy for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a critical analysis of currently available drugs, treatment schedules, and long-term results". European Urology. 53 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.015. PMID 17719169.

- ^ Di Stasi SM, Riedl C (June 2009). "Updates in intravesical electromotive drug administration of mitomycin-C for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer" (PDF). World Journal of Urology. 27 (3): 325–30. doi:10.1007/s00345-009-0389-x. hdl:2108/6440. PMID 19234707.

- ^ Kos, Bor; Vásquez, Juan Luis; Miklavčič, Damijan; Hermann, Gregers G G; Gehl, Julie (2016). "Investigation of the mechanisms of action behind Electromotive Drug Administration (EMDA)". PeerJ. 4 (e2309): e2309. doi:10.7717/peerj.2309. PMC 5012313. PMID 27635313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nativ O, Witjes JA, Hendricksen K, et al. (October 2009). "Combined thermo-chemotherapy for recurrent bladder cancer after bacillus Calmette-Guerin". The Journal of Urology. 182 (4): 1313–7. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.017. PMID 19683278.

- ^ Colombo R, Da Pozzo LF, Salonia A, et al. (December 2003). "Multicentric study comparing intravesical chemotherapy alone and with local microwave hyperthermia for prophylaxis of recurrence of superficial transitional cell carcinoma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 21 (23): 4270–6. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.01.089. PMID 14581436.

- ^ Alfred Witjes J, Hendricksen K, Gofrit O, Risi O, Nativ O (June 2009). "Intravesical hyperthermia and mitomycin-C for carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder: experience of the European Synergo working party". World Journal of Urology. 27 (3): 319–24. doi:10.1007/s00345-009-0384-2. PMC 2694311. PMID 19234857.

- ^ Halachmi S, Moskovitz B, Maffezzini M, et al. (April 2009). "Intravesical mitomycin C combined with hyperthermia for patients with T1G3 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder". Urologic Oncology. 29 (3): 259–264. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.02.012. PMID 19395285.

- ^ Alexandroff AB, Jackson AM, O'Donnell MA, James K (May 1999). "BCG immunotherapy of bladder cancer: 20 years on". Lancet. 353 (9165): 1689–94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07422-4. PMID 10335805.

- ^ Lamm, Donald L.; Blumenstein, Brent A.; Crawford, E. David; Montie, James E.; Scardino, Peter; Grossman, H. Barton; Stanisic, Thomas H.; Smith Jr, Joseph A.; Sullivan, Jerry; Sarosdy, Michael F.; Crissman, John D.; Coltman, Charles A. (1991). "A Randomized Trial of Intravesical Doxorubicin and Immunotherapy with Bacille Calmette–Guérin for Transitional-Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder". New England Journal of Medicine. 325 (17): 1205–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199110243251703. PMID 1922207.

- ^ Kuroda, K; Brown, EJ; Telle, WB; Russell, DG; Ratliff, TL (January 1993). "Characterization of the internalization of bacillus Calmette-Guerin by human bladder tumor cells". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 91 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1172/JCI116202. PMC 329996. PMID 8423234.

- ^ Ratliff, TL; Ritchey, JK; Yuan, JJ; Andriole, GL; Catalona, WJ (September 1993). "T-cell subsets required for intravesical BCG immunotherapy for bladder cancer". The Journal of Urology. 150 (3): 1018–23. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35678-1. PMID 8102183.

- ^ Fuge, O; Vasdev, N; Allchorne, P; Green, JS (2015). "Immunotherapy for bladder cancer". Research and Reports in Urology. 7: 65–79. doi:10.2147/RRU.S63447. PMC 4427258. PMID 26000263.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Witjes JA (May 2006). "Management of BCG failures in superficial bladder cancer: a review". European Urology. 49 (5): 790–7. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.017. PMID 16464532.

- ^ Babjuk W, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al. (2010). "Guidelines on TaT1 (Non-muscle invasive) Bladder Cancer". European Association of Urology. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010.

- ^ Bladder Cancer Clinical Guideline Update Panel (2007). Bladder Cancer: Guideline for the Management of Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: (Stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 Update. American Urological Association.[page needed]

- ^ "UpToDate: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy". www.uptodate.com.

- ^ Advanced Bladder Cancer Meta-analysis, Collaboration. (7 June 2003). "Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 361 (9373): 1927–34. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13580-5. PMID 12801735.

- ^ Advanced Bladder Cancer (ABC) Meta-analysis Collaboration (August 2005). "Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: update of a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data advanced bladder cancer (ABC) meta-analysis collaboration". Eur. Urol. 48 (2): 202–5, discussion 205–6. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.04.006. PMID 15939524.

- ^ Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, et al. (August 2003). "Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 349 (9): 859–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022148. PMID 12944571.

- ^ a b Yin, M; Joshi, M; Meijer, RP; Glantz, M; Holder, S; Harvey, HA; Kaag, M; Fransen van de Putte, EE; Horenblas, S; Drabick, JJ (June 2016). "Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Two-Step Meta-Analysis". The Oncologist. 21 (6): 708–15. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0440. PMC 4912364. PMID 27053504.

- ^ Ploussard, G; Daneshmand, S; Efstathiou, JA; Herr, HW; James, ND; Rödel, CM; Shariat, SF; Shipley, WU; Sternberg, CN; Thalmann, GN; Kassouf, W (July 2014). "Critical analysis of bladder sparing with trimodal therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review". European urology. 66 (1): 120–37. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.038. PMID 24613684.

- ^ Smelser WW, Austenfeld MA, Holzbeierlein JM, Lee EK. Where are we with bladder preservation for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in 2017?. Indian J Urol 2017;33:111–7 http://www.indianjurol.com/text.asp?2017/33/2/111/203415 Archived 10 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mirza, A; Choudhury, A (27 April 2016). "Bladder Preservation for Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer". Bladder cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2 (2): 151–163. doi:10.3233/BLC-150025. PMID 27376137.

- ^ a b "Treatment of Non-Metastatic Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/ASCO/ASTRO/SUO Guideline (2017) - American Urological Association". www.auanet.org. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "EAU Guidelines: Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer". Uroweb.

- ^ Lyman, GH; Dale, DC; Culakova, E; Poniewierski, MS; Wolff, DA; Kuderer, NM; Huang, M; Crawford, J (October 2013). "The impact of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on chemotherapy dose intensity and cancer survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 24 (10): 2475–84. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt226. PMID 23788754.

- ^ Gerullis, H; Wawroschek, F; Köhne, CH; Ecke, TH (January 2017). "Vinflunine in the treatment of advanced urothelial cancer: clinical evidence and experience". Therapeutic advances in urology. 9 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1177/1756287216677903. PMID 28042310.

- ^ Siddiqui, MR; Grant, C; Sanford, T; Agarwal, PK (August 2017). "Current clinical trials in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer". Urologic Oncology. 35 (8): 516–527. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.06.043. PMC 5556973. PMID 28778250.

- ^ "Bladder Cancer - Statistics". Cancer.Net. 25 June 2012.

- ^ Kaufman, DS; Shipley, WU; Feldman, AS (18 July 2009). "Bladder cancer". Lancet. 374 (9685): 239–49. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60491-8. PMID 19520422.

- ^ van der Heijden, Antoine G.; Witjes, J. Alfred (September 2009). "Recurrence, Progression, and Follow-Up in Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer". European Urology Supplements. 8 (7): 556–562. doi:10.1016/j.eursup.2009.06.010.

- ^ "Bladder cancer statistics". World Cancer Research Fund. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Greece Factsheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ GBD 2017 Causes of Death, Collaborators. (10 November 2018). "Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". Lancet. 392 (10159): 1736–1788. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. PMC 6227606. PMID 30496103. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Lakkis, NA; Adib, SM; Hamadeh, GN; El-Jarrah, RT; Osman, MH (2018). "Bladder Cancer in Lebanon: Incidence and Comparison to Regional and Western Countries". Cancer Control : Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 25 (1): 1073274818789359. doi:10.1177/1073274818789359. PMC 6055109. PMID 30027755.

- ^ a b Hemelt M, Zeegers MP (2000). "The effect of smoking on the male excess of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis and geographical analyses". Int J Cancer. 124 (2): 412–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.23856. PMID 18792102.

- ^ "Scientists Find One Reason Why Bladder Cancer Hits More Men". University of Rochester Medical Center. 20 April 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ Marks, P; Soave, A; Shariat, SF; Fajkovic, H; Fisch, M; Rink, M (October 2016). "Female with bladder cancer: what and why is there a difference?". Translational Andrology and Urology. 5 (5): 668–682. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.03.22. PMC 5071204. PMID 27785424.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Canada Fact Sheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "China Fact Sheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Obvervatory. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "UK fact sheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

External links

- Bladder cancer at Curlie

- Clinically reviewed bladder cancer information for patients, from Cancer Research UK

- Cancer.Net: Bladder Cancer

- EORTC calculator for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer risk stratification