1 Parachute Battalion

| 1 Parachute Battalion | |

|---|---|

Insignia & Beret | |

| Active | 1 April 1961 – present |

| Country | |

| Branch |

|

| Type | Infantry (paratroopers) |

| Role | Airborne Infantry |

| Size | Battalion |

| Garrison/HQ | Tempe, Bloemfontein |

| Nickname(s) | Parabats |

| Motto(s) | Ex alto vincimus (We conquer from Above) |

| Battle honours | Battle for Bangui |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Lt. Col. D. Mziki |

| Notable commanders |

|

1 Parachute Battalion (Ex Alto Vincimus)[1] is the only full-time paratroop unit of the South African Army. It was established on 1 April 1961 with the formation of the Parachute Battalion. After 1998 this unit was renamed to Parachute Training Centre. It was the first battalion within 44 Parachute Brigade until 1999 when the brigade was downsized to 44 Parachute Regiment

The battalion has performed many active operations in battle – producing many highly decorated soldiers – in the South African Border War from 1966 to 1989. Their best known action was the controversial Battle of Cassinga in 1978.[2]

The unit's nickname "Parabat" is a portmanteau derived from the words "Parachute Battalion".

History

In 1960 fifteen volunteers from the SADF were sent to England, the majority to train as parachute instructors, some as parachute-packers and one SAAF pilot in the dropping of paratroopers. These formed the nucleus of 1 Parachute Battalion at Tempe in Bloemfontein. The first paratroopers were Permanent Force men, but soon the training of Citizen Force (similar to the National Guard of the United States) paratroopers commenced. Members of 1 Parachute Battalion were the first S.A. Army men to see action after WWII when, in 1966, they participated, with the South African Police, against insurgents in S.W.A. (now Namibia).[3]

In 1966, members of 1 Parachute Battalion participated in the first action in the war in South West Africa during a heliborne assault on an insurgent base. Thereafter, they were involved in operations in SWA/Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Mozambique and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and elsewhere on an almost constant basis for over 20 years.

1 Parachute Bn. was organised as follows:

- Permanent Force:

- Bn H.Q.,

- H.Q. Coy and

- A and B Coy's;

- Citizen Force:

- C Coy Cape Town,

- D Coy Durban,

- E Coy Pretoria and

- F Coy Johannesburg

Further battalions were added: 2 Para Bn in 1971 and 3 Para Bn in 1977.

In 1974 and 1975 1 Parachute Battalion operated along the Angolan border with S.W.A; along the Caprivi Strip; a platoon jumped near Luiana (September 1975), Angola to relieve a group of "Bushmen" trapped by a SWAPO force; and 3 platoons Joined Operation Savannah at Sá da Bandeira the day after the airport was taken (October 1975). The two platoons withdrew in February/March Operation Savannah during the Angolan Civil War in July 1975 when 1 string of 1 Parachute Battalion were flown to Ondangwa and travelled by Unimog to Ruancana on the northern border of SWA at Ruacana and Santa Clara in Angola to relieve two Portuguese communities trapped by the MPLA.

With the coming of 44 Parachute Brigade in April 1978, under the leadership of Brigadier M J du Plessis and Colonel Jan Breytenbach, a co-founder of the brigade. it became a powerful force. The first large airborne exercise of the Parachute Battalion Group took place in 1987 in the Northwestern Transvaal (now North West Province). With the eventual disbanding of 44 Parachute Brigade its full-time personnel were moved to Bloemfontein and incorporated into the 1 Parachute Battalion Group.

In 1986, the unit embarked on its first HALO/HAHO (High altitude Low Opening/High Altitude High Opening) course in Bloemfontein. This would enable the troops to drop into enemy territory from aircraft following commercial routes.

In 2001 battalion personnel formed the spearhead of the South African Protection Support Detachment deploying to Burundi.[4]

In 2012, 1 Parachute Battalion participated in the South African military assistance to the Central African Republic operation, where the unit suffered 13 killed, with 27 injured and one missing in action in an ambush conducted by Séléka rebels.[5] In 2014 it was announced that 1 Parachute Battalion would receive Battle Honours for this operation.[6]

In 2013, the battalion contributed one company, under command of Major Vic Vrolik, to the FIB which fought a number of engagements in the DRC.[7]

Training

1 Parachute Battalion is the sole military parachute training institution in South Africa, with its parachute School being responsible for all training. The school has had only four fatalities in its existence. 1 Parachute Battalion is a full-time unit which in addition to parachute training also conducts force training to national servicemen inducted into the unit and other units in the South African Army.

The average age ranges in the mid-twenties. The selection and training of today's paratroops remains exceptionally rigorous to ensure that the standard of combat efficiency is retained at a high level. Generally, members of 1 Parachute Battalion visit the various battalions each year early in the training cycle to look for volunteers. These must then pass a physical test at their unit prior to appearing before a selection board, which examines their character and motivation.

To give would-be members the endurance and the fitness they will need for operations in the harsh African conditions, the instructors of 44 Parachute Brigade place particular emphasis on basic physical training. Young men volunteering for service with the parachute forces first undergo a battery of medical tests – as stringent as that for flying personnel – before setting off on a 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) timed run. Before they can recover their breath, they tackle the second test: 200 metres (0.12 mi) run in which each man carries a comrade on his back.

The applicants are then put through various psychological and physical tests – though these are usually well within the reach of anyone with sufficient motivation and willpower. The real ordeal will then start: for four long months, the recruits Bats will endure forced marches, physical exercises, shooting sessions and inspections — all this barracked by the screams of their eagle-eyed instructors. The South African paratroop instructors, like their British counterparts, enforce strict discipline. For example, trainees always take their grooming kit along with them on 30 kilometres (19 mi) marches and at dawn, when back at the base with aching bones, devote whatever little time is left they have to rest to 'spit and polish'.

Those who are accepted are then transferred to 1 Para, where they first complete the normal three-month basic training course, with some differences: PT three times a day, no walking in camp under any circumstances and a 10 to 15 kilometres (6.2 to 9.3 mi) run to end each day. 20 kilometres (12 mi) runs carrying tar poles; car tyres attached to the candidates by a long rope; or the dreaded 25 kilograms (55 lb) concrete slab that has to be carried everywhere the candidate goes. Some 10 to 20 percent drop out during this phase, returning to their original units. All this builds up to what is called the koeikamp ('cow camp'). It is 3 days of the ultimate challenge of physical and psychological endurance.

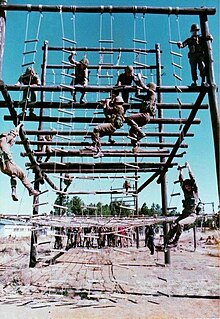

The would-be paratroops get a 24-hour ration pack or "rat pack" for the duration of the selection. During these days, they are given several tasks to perform in an allocated time: Several 20 to 30 kilometres (12 to 19 mi) Night marches/runs with 25 kilograms (55 lb) bergens, boxing, 75 kilograms (165 lb) stretcher run over 20 kilometres (12 mi), digging trenches and the carrying of artillery canisters over 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) during a timed run are just a few of the tasks that has to be completed. On top of all this the candidates are out in the African bush with no showers, hot meals or beds after each gruelling day. Each year the sequence of what "tests" will be done to get the strongest out of the "wannabees" changes, so it comes as quite a surprise each year. Due to lack of sleep, hunger and extreme physical tasks many of the men give up. After all the above tests, the few remaining soldiers head back to camp where they have to complete an obstacle course called the "Elephant". Some foreign Elite soldiers claimed this to be one of the hardest bone breaking obstacle courses ever.[2] Again, this is a timed exercise, which has to be completed several times, it is also done with full battle kit. Again the instructors are looking for any hesitant students during the high obstacles and underwater swim through a narrow tunnel. At the end of the "Elephant" several more students drop out due to injury or not completing the course in the required time. At this point the course has been completed. However, there is always the 'bad surprise" which has historically become part of the Selection Phase.

After a six-month ordeal, the selected few (about 40% of the original intake), make the 12 jumps required to obtain their wings. During this time, the chances of being disqualified are still very high. This phase is followed by some advanced individual training, during which such subjects as advanced driving, demolitions, tactics and patrolling, unarmed combat, survival skills, escape and evasion, aspects of guerrilla warfare, tracking, raiding, counter-insurgency operations, fast rope skills, ambush and anti-ambush techniques and foreign weapons and techniques are covered.

Their instructors, however, always find that something is left to be desired with the inspection which invariably follows. To harden their muscles, trainees are made to carry a telegraph pole for two days, at a rate of 20 kilometres (12 mi) daily. Back at base, the 'marble', a stone weighing about 25 kilograms (55 lb) which the soldier must carry wherever he goes, is used as a substitute for the same purpose. The detailed training programme is listed below:

Basic training – 10 weeks

- Musketry

- Field Craft

- Drill

- Map Reading

- Buddy Aid

- Physical Training – Very important

Parachute qualification training – 5 weeks

- Parachute Selection – 2 Weeks (8 hours Physical Training every day for 2 weeks)

- Running 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) and more with boots

- Running up to 21 kilometres (13 mi) with logs

- Battle PT with Logs, Concrete Blocks and Rifles

- Route Marches of 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) with full kit

- Boxing, Soccer, Wrestling, Rugby with Car Tyre as ball

- Callisthenic Exercises

- Qualification Tests (60% must be attained after the 2 weeks Parachute Selection)

- 3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi) with full kit in 18 minutes

- 40 Shuttle Runs in 90 seconds

- 200 metres (0.12 mi) fireman's lift with full kit

- Climb a 6-metre rope

- Climb over a 2-metre wall with full kit

- 50 pushups without resting

- 67 sit-ups in 2 minutes

- 120 squat kicks without resting

- Parachute training – 3 weeks following successful parachute selection

- Ground training in hangar

- Jumping from "aapkas" (Outdoor exit trainer)

- Jumping from Dakota Aircraft

- Jumping from C130 / C160 Transall Aircraft

- Jumping includes day and night jumps, with and without kit using standard and steerable parachutes

- A total of 8 jumps must be completed before the sought after paratrooper wings are awarded

- Current Day Selection and Training for the Physical portion of the Parachute Course

- Until 1991 the physical portion of the Parachute Qualifying course was 2 weeks, but due to national service being shortened to one year, the army had a need to change and make the training more compact and fast paced. However some of the 'older' paratroops still do physical training courses to ensure that standards do not drop.

Individual training – 8 weeks

- Platoon Weapons

- Battle Craft

- Specialist Training (in one of the following mustering)

- Section Leaders

- Rifleman

- Mortar man

- Anti-Tank Gunner

- Machine Gunner

- Signaler

- Intelligence NCO

- Medical Orderly

- Driver

- Clerk

- Parachute Packer

- Store man

Conventional warfare training – 10 weeks

- Advance

- Defence

- Withdrawal

- Cooperation with Armoured, Artillery, Air Force etc.

- Airborne Operations including Air Assault battle handling on sub-unit level

Counter-insurgency (COIN) training – 9 weeks

- Bush Warfare Techniques

- Reaction Force Operations

- Specialized Air Operations

- Airborne Raids

Active operational duty

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2015) |

- Once a paratroop is fully trained, he takes part in the normal operational and training activities of the unit.

Other Training

- Specialist Parachute and other Training Courses include:[2]

- Pathfinder Training

- Basic fast-roping/rapelling skills

Fast roping from a South African Air Force Atlas Oryx - Fast-roping/rapelling dispatchers

- Fast-roping/rapelling instructors

- Static Line dispatchers course

- Basic Parachute instructors course

- Advance static line jump course

- Basic Free Fall Course

- Free fall dispatchers course

- Free fall instructors course

- Advanced free fall course

- Advanced free fall instructors course

- Drop zone safety officers course

- Parachute Packing and checking course

- Tandem parachuting

Leadership

| From | Commanding Officers | To |

| 1966 | Lt Gen Willem Louw SSA SM[1]: 255 | 1967 |

| 2 November 2024 | Brig Gen Renier (Doibi) Coetzee PS | 2 November 2024 |

| From | Regimental Sergeants Major | To |

References

- ^ a b Els, Paul J WO1 (2010). We conquer from above. PelsA Books. ISBN 978-0-620-46738-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c McGill Alexander, Edward (July 2003). The Cassinga Raid (MA Thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 44 Parachute Brigade 1997 – Col Skillie van der Walt

- ^ http://www.saairforce.co.za/news-and-events/140/south-african-

- ^ http://mg.co.za/article/2013-03-26-sandf-releases-names-of-sa-soldiers-killed-in-car

- ^ Helfrich, Kim (19 February 2014). "Battle honours for three SANDF units". DefenceWeb. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ Hofstatter, Stephan; Oatway, James (22 August 2014). "South Africa at war in the DRC - The inside story". Times Live. Sunday Times. Retrieved 22 September 2014.