Albert Gore Sr.

Albert Gore Sr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

| In office January 3, 1953 – January 3, 1971 | |

| Preceded by | Kenneth D. McKellar |

| Succeeded by | Bill Brock |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 4th district | |

| In office January 3, 1939 – January 3, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | John R. Mitchell |

| Succeeded by | Joe L. Evins |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Albert Arnold Gore December 26, 1907 Granville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | December 5, 1998 (aged 90) Carthage, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Resting place | Smith County Memorial Gardens Carthage, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Pauline LaFon Gore |

| Children | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1944 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Albert Arnold "Al" Gore Sr. (December 26, 1907 – December 5, 1998), known simply as Al Gore before the fame of his son, was an American politician, who served as a U.S. Representative and a U.S. Senator for the Democratic Party from Tennessee. He was the father of Al Gore, the 45th Vice President of the United States (1993–2001).

Early years

Gore was born in Granville, Tennessee, the third of five children of Margie Bettie (née Denny) and Allen Arnold Gore.[1][2] Gore's ancestors include Scots-Irish immigrants who first settled in Virginia in the mid-18th century and moved to Tennessee after the Revolutionary War.[3][fn 1]

Gore studied at Middle Tennessee State Teachers College and graduated from the Nashville Y.M.C.A. Night Law School, now the Nashville School of Law. He first sought elective public office at age 23, when he ran unsuccessfully for the job of superintendent of schools in Smith County, Tennessee. A year later he was appointed to the position after the man who had defeated him died.[5]

Congressional career

After serving as Commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Labor from 1936 to 1937, Gore was elected as a Democrat to the 76th Congress in 1938, re-elected to the two succeeding Congresses, and served from January 3, 1939 until he resigned on December 4, 1944 to enter the U.S. Army.[6]

Gore was re-elected to the 79th and to the three succeeding Congresses (January 3, 1945 to January 3, 1953). In 1951, Gore proposed in Congress that "something cataclysmic" be done by U.S. forces to end the Korean War: a radiation belt (created by nuclear weapons) dividing the Korean peninsula permanently into two.[7]

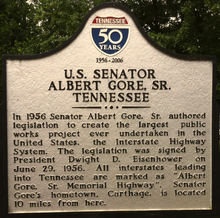

Gore was not a candidate for House re-election but was elected in 1952 to the U.S. Senate. In his 1952 election, he defeated six-term incumbent Kenneth McKellar. Gore's victory, coupled with that of Frank G. Clement for governor of Tennessee over incumbent Gordon Browning on the same day, is widely regarded as a major turning point in Tennessee political history and as marking the end of statewide influence for E. H. Crump, the Memphis political boss. During this term, Gore was instrumental in sponsoring and enacting the legislation creating the Interstate Highway System. Gore was re-elected in 1958 and again in 1964, and served from January 3, 1953, to January 3, 1971, after he lost reelection in 1970. In the Senate, he was chairman of the Special Committee on Attempts to Influence Senators during the 84th Congress.

Gore was one of only four Democratic senators from the former Confederate states who did not sign the 1956 Southern Manifesto opposing integration, the others being Ralph Yarborough and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas (who was not asked to sign), and Tennessee's other senator, Estes Kefauver. South Carolina Senator J. Strom Thurmond tried to get Gore to sign the Southern Manifesto, but Gore refused. Gore could not, however, be regarded as an integrationist, as he voted against some major civil rights legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 although he supported the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Gore easily won renomination in 1958 over former governor Jim Nance McCord. In those days, Democratic nomination was still tantamount to election in Tennessee since the Republican Party was largely nonexistent in most of the state. In 1964, he faced an energetic Republican challenge from Dan Kuykendall, chairman of the Shelby County (Memphis) GOP, who ran a surprisingly strong race against him. While Gore won, Kuykendall held him to only 53 percent of the vote, in spite of Johnson's massive landslide victory in that year's presidential election.

By 1970, Gore was considered to be fairly vulnerable for a three-term incumbent Senator, as a result of his liberal positions on many issues such as the Vietnam War and civil rights. This was especially risky, electorally, as at the time Tennessee was moving more and more toward the Republican Party. He faced a spirited primary challenge, predominantly from former Nashville news anchor Hudley Crockett, who used his broadcasting skills to considerable advantage and generally attempted to run to Gore's right. Gore fended off this primary challenge, but he was ultimately unseated in the 1970 general election by Republican Congressman Bill Brock. Gore was one of the key targets in the Nixon/Agnew "Southern strategy." He had earned Nixon's ire the year before when he criticized the administration's "do-nothing" policy toward inflation. In a memo[8] to senior advisor Bryce Harlow, Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield relayed the President's desire that Gore be "blistered" for his comment.[9] Spiro T. Agnew traveled to Tennessee in 1970 to mock Gore as the "Southern regional chairman of the Eastern Liberal Establishment". Other prominent issues in this race included Gore's opposition to the Vietnam War, his vote against Everett Dirksen's amendment on prayer in public schools, and his opposition to appointing Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell to the U.S. Supreme Court. Brock won the election by a 51% to 47% margin.

Political legacy

In 1956, he gained national attention after his disapproval of the Southern Manifesto. Gore voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, in fact filibustering against it, although he supported the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Gore was a vocal champion of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which secured creation of interstate highways. Later, he backed the Great Society array of programs initiated by President Johnson's administration, and introduced a bill with a Medicare blueprint. In international politics, he moved from proposing in the House to employ nuclear weapons for establishing a radioactive demilitarized zone during the Korean War, to voting for the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and speaking against the Vietnam War, which cost him his Senate seat in 1970.[10]

Later life

After leaving Congress, Gore resumed the practice of law and also taught law at Vanderbilt University. He continued to represent the Occidental Petroleum where he became vice president and member of the board of directors. Gore became chairman of Island Creek Coal Co., Lexington, Kentucky, an Occidental subsidiary, in 1972, and in his last years operated an antiques store in Carthage—Gore Antique Mall.[11]

Personal life

On April 17, 1937, Gore married lawyer Pauline LaFon (1912–2004), the daughter of Maude (née Gatlin) and Walter L. LaFon. Together, they had two children:

- Nancy LaFon Gore (1938–1984), who died of lung cancer

- Albert Gore Jr. (born 1948), who followed in his father's political footsteps in the Democratic Party representing Tennessee as a U.S. Representative and Senator, and later serving as Vice President of the United States under Bill Clinton.

He died three weeks shy of his 91st birthday and is buried in Smith County Memorial Gardens in Carthage. The stretch of Interstate 65 in Tennessee has been named The Albert Arnold Gore Sr. Memorial Highway in honor of him.[5]

Footnotes

- ^ During a December 1987 interview with Playboy, Gore Vidal, a maternal grandson of Thomas Gore suggested that Albert Gore was of Anglo-Irish descent, rather than Scots-Irish. Vidal believed that Albert Gore was his sixth or seventh-generation cousin.[4]

References

- ^ Turque, Bill. "Inventing Al Gore". New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Partial Genealogy of the Gores, CLP Research

- ^ Turque (2000), p. 5

- ^ Turque (2000), p. 378

- ^ a b Molotsky, Irvin (7 December 1998). "Albert Gore Sr., Veteran Politician, Dies at 90". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "GORE, Albert Arnold, (1907 - 1998)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ George Mason University’s History News Network. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- ^ Memo from Alexander Butterfield to Bryce Harlow, July 10, 1969, Nixon Library

- ^ Radnofsky, Louise (2010-12-10) Documents Show Nixon Ordered Jews Excluded From Israel Policy, Wall Street Journal

- ^ Edward L. Lach Jr. Gore, Albert Sr. American National Biography Online. September 2000. retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Gore opens antique mall, Times Daily, January 3, 1994.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

This article incorporates public domain material from the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

Bibliography

- Turque, Bill, Inventing Al Gore, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000, ISBN 0-618-13160-4

External links

- United States Congress. "Albert Gore Sr. (id: G000320)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Washington Post "Political Junkie" column: answers questions about Gore's civil rights record

- "Casting a Long Shadow", by David M. Shribman: Boston Globe article describing 1970 congressional races of Al Gore Sr., and George H. W. Bush.

- "Sons", by Nicholas Lemann: article on Albert A. Gore Jr., and George W. Bush, including some description of the former's relationship with his father.

- FBI files on Albert Gore Sr.[permanent dead link]

- The Life of Albert Gore Sr.

- Oral History Interviews with Albert Gore (Part 1, Part 2) from Oral Histories of the American South

- 1907 births

- 1998 deaths

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- Burials in Tennessee

- Democratic Party United States Senators

- Gore family

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee

- Middle Tennessee State University alumni

- Nashville School of Law alumni

- People from Jackson County, Tennessee

- People from Smith County, Tennessee

- State cabinet secretaries of Tennessee

- Tennessee Democrats

- United States Senators from Tennessee

- United States vice-presidential candidates, 1956

- Vanderbilt University faculty

- Washington, D.C. lawyers

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 20th-century American politicians