Bronx International Exposition of Science, Arts and Industries

| Bronx International Exposition of Science, Arts and Industries | |

|---|---|

Newspaper ad for the fair | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Unrecognized exposition |

| Name | Bronx International Exposition of Science, Arts and Industries |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| City | Bronx, New York City |

| Venue | Starlight Park |

| Coordinates | 40°50′13″N 73°52′48″W / 40.83694°N 73.88000°W |

The Bronx International Exposition of Science, Arts and Industries was a world's fair[1] held in the Bronx, New York City, United States, in 1918. Meant to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Bronx's settlement,[2] it failed to become popular, as the exposition was held during World War I. After the exposition ended, the site was used for an amusement park called Starlight Park.

Planning

[edit]In 1914, the New York City borough of the Bronx was separated from New York County (which included Manhattan) to become Bronx County. At the time, the borough was growing quickly due to the expansion of the subway, and the Bronx Borough Courthouse had just been completed.[3] To draw attention to the newly independent county, numerous persons sought to create a world's fair in the borough. The West Farms area on the west bank of the Bronx River, in the south-central part of the Bronx, was seen as an optimal site for such a fair, as it was located close to the subway and could be accessed by ferries.[4] The site had originally contained the estate of politician William Waldorf Astor.[5][6][7] The fair was also intended to inspire real estate development in the area.[2] The project's director, Harry F. McGarvie, who had worked at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in 1914, signed a 21-year lease for the site.[7]

Although planning for the fair coincided with the start of World War I in August 1914, organizers believed that the war would be over quickly.[4] However, when a groundbreaking ceremony was hosted on August 1, 1916, the war was still ongoing, and news of the groundbreaking was overshadowed by the Black Tom explosion in New York Harbor, which had occurred two days prior.[4] The U.S. Congress refused to provide funding for the world's fair due to the ongoing war and issues with the proposed large Latin American buildings at the fair.[4][7] The New York, Westchester and Boston Railway declined to build a train station for the fair, even though the railroad's line ran right next to the fair site.[4] In November 1917, the organizers bought land on Tremont Avenue to create an entrance for the fair.[8] The job employed over 400 workers.[9]

Operation

[edit]

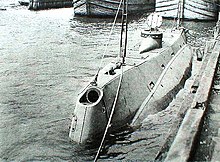

The Bronx World's Fair was originally supposed to open on May 30, 1918, one year after the Bronx's 300th anniversary of its settlement, and was to run for five months per year.[10][11] At the time, they expected that the fair could be converted into a permanent attraction after 1918,[6] and it was marketed as the city's first "permanent exposition".[12] The actual opening was not until the following month.[a] The fair was located on a 28-acre (11 ha) site at Exposition Park on the east bank of the Bronx River at 177th Street and Devoe Avenue.[6] Amusement park rides and exhibition halls operated next to each other.[14] The free attractions at the Bronx World's Fair included various sideshows such as a "Comedy Circus"; the Lunette Sisters; performances by high-diver Kearney P. Speedy; and a "monkey cabaret".[5] Another attraction at the fair was the submarine USS Holland.[15][16]

The fair's initial intention was to "attract foreign trade to this country after the war."[6] Organizers had received applications from numerous countries to host exhibits at the fair.[17] The organizers also planned for dozens of buildings to eventually be erected at the fair; estimates ranged from 70 to more than 100.[6][11][16] The swimming pool at the Bronx World's Fair was marketed as the world's largest saltwater pool, measuring 300 by 350 feet (91 by 107 m) with a capacity of 2,500,000 U.S. gallons (9,500,000 L), and ranging from 0 to 10 feet (0.0 to 3.0 m) deep. The pool contained diving boards and a wave pool machine at the deep end, as well as a 50-by-55-foot (15 by 17 m) beach with sand brought from Rockaway, Queens.[18][16] The fair also contained a scenic ridable miniature railway on the Bronx River, a "mountain" exhibit with a 65-foot-tall (20 m) waterfall, and a hotel nearby.[19] LaMarcus Adna Thompson built a roller coaster at the site, while the Eli Bridge Company's Ferris wheel from the Panama–California Exposition was brought over to the Bronx World's Fair.[16] Other attractions included a bathing pavilion that could fit 4,500 people; a convention center; and 15 large pavilions, including Chinese and North Sea-themed pavilions, as well as those for fine arts, liberal arts, and American achievements.[11][16]

Plans for a true world's fair did not materialize. The only country to actually exhibit there was Brazil.[4] As a result, the fair failed after its first year, and the attractions were repurposed into Starlight Park, an amusement park that continued to operate through the mid-1930s. The "exhibition hall" became an ice rink and dance hall, and more amusement attractions were added.[20] In December 1920 the Bronx Expositions Corporation was the subject of a breach of contract lawsuit filed by Exposition Catering,[21] which at the time was one of the largest lawsuits filed in the entertainment industry.[22] According to the lawsuit, the Expositions Corporation had failed to uphold a contract to build an elaborate entrance, a convention center, and a permanent exposition, and had instead erected "a cheap amusement park" because of their mismanagement of money.[23][21] The outcome of the lawsuit was unknown and McGarvie died in 1922.[23]

The United States Army took over the site between 1942 and 1946, while the northeastern part of the site became the West Farms Depot of MTA Regional Bus Operations.[24] In the late 1950s, a city park called Starlight Park opened on the riverbank opposite the original amusement park and exhibition site.[25][26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

Citations

- ^ Findling, John E.; Pelle, Kimberley D. (eds.). "Appendix D: Fairs Not Included". Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 427. ISBN 978-0-7864-3416-9.

- ^ a b Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 91.

- ^ DeVillo 2015, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d e f g DeVillo 2015, p. 149.

- ^ a b "The Bronx World's Fair of 1918: the failure which became a magical park". The Bowery Boys: New York City History. September 13, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Crowds See Opening Of Trade Exposition; Police Commissioner Enright Receives Keys for City at Formal Opening. Permanent Show Planned; Borough President Bruckner Thanks Promoters for Choosing Site in the Bronx". The New York Times. June 30, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 92.

- ^ "Latest Dealings in the Realty Field". The New York Times. November 4, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Making of America Project & Nature Publishing Group 1918, p. 524–525.

- ^ "The Bronx Exposition; To Open May 30 and to Remain Open Five Months Each Year". The New York Times. May 5, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Bronx International Exhibition". New-York Tribune. October 14, 1917. pp. 6–7. Retrieved October 2, 2019 – via The Library of Congress.

- ^ Making of America Project & Nature Publishing Group 1918, p. 524.

- ^ "Bronx to Have World Mart; Permanent Industrial Exposition Will Open June 29". The New York Times. June 23, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (March 22, 1992). "Streetscapes: The New York Coliseum; From Auditorium To Bus Garage to . . ". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Making of America Project & Nature Publishing Group 1918, p. 525.

- ^ a b c d e Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 93.

- ^ "Assails 'Puritans' Sunday'; Dr. Fitch Says Working People Have Right to Recreation". The New York Times. July 17, 1916. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Making of America Project & Nature Publishing Group 1918, p. 536.

- ^ Making of America Project & Nature Publishing Group 1918, p. 536–537.

- ^ DeVillo 2015, p. 150.

- ^ a b "Asks $5,000,000 Damages; Bronx Catering Company Sues Exposition for Contract Breach". The New York Times. December 15, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 95.

- ^ a b Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 96.

- ^ Valentino, Elisa (July 12, 2018). "WEEKDAY MAGAZINE – Starlight Park: A Century of Bronx History – Part 2". This Is The Bronx. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ DeVillo 2015, p. 152.

- ^ "Starlight Park Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

Sources

- DeVillo, S.P. (2015). The Bronx River in History & Folklore. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-62585-490-2.

- Gottlock, B.; Gottlock, W. (2013). Lost Amusement Parks of New York City: Beyond Coney Island. Lost. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62584-556-6.

- Making of America Project; Nature Publishing Group (1918). Scientific American. Library of American civilization. Munn & Company. pp. 524–525, 536–538. Retrieved October 2, 2019.