Carbonated water

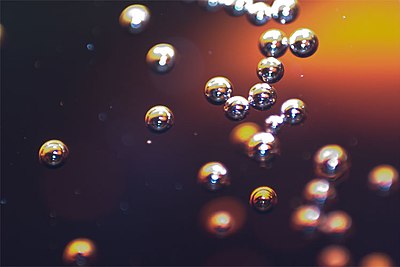

Carbonated water (also known as club soda, soda water, sparkling water, seltzer, bubbles aguita or fizzy water) is water into which carbon dioxide gas under pressure has been dissolved, a process that causes the water to become effervescent.

Carbonated water is the defining ingredient of carbonated soft drinks. The process of dissolving carbon dioxide in water is called carbonation.

Etymology

In the US, carbonated water was known as soda water until WWII, due to the sodium salts it contained. These were added as flavoring and acidity regulators with the intent of mimicking the taste of natural mineral water.

During the Great Depression, it was sometimes called "two cents plain," a reference to its being the cheapest drink at soda fountains. In the 1950s, terms such as sparkling water and seltzer water gained favor. The term seltzer water is a genericized trademark that derives from the German town Selters, which is renowned for its mineral springs.[1] Naturally carbonated water has been commercially bottled and shipped from this town since the 18th century or earlier. Generally, seltzer water has no added sodium salts, while club soda still retains the sodium salts.

In many parts of the US, soda has come to mean any type of sweetened, carbonated soft drink.

Chemistry and Physics

Carbon dioxide dissolved in water at a low concentration (0.2%–1.0%) creates carbonic acid (H

2CO

3),[2] which causes the water to have a slightly sour taste with a pH between 3 and 4.[3] An alkaline salt, such as sodium bicarbonate, may be added to soda water to reduce its acidity.

The amount of a gas like carbon dioxide that can be dissolved in water is described by Henry's Law. Water is chilled, optimally to just above freezing, in order to permit the maximum amount of carbon dioxide to dissolve in it. Higher gas pressure and lower temperature cause more gas to dissolve in the liquid. When the temperature is raised or the pressure is reduced (as happens when a container of carbonated water is opened,) carbon dioxide comes out of solution, in the form of bubbles.[citation needed]

Manufacture

Commercial

The process of dissolving carbon dioxide in water is called carbonation. Commercial soda water in siphons is made by chilling filtered plain water to 8 °C (46 °F) or below, optionally adding a sodium or potassium based alkaline compound such as sodium bicarbonate to reduce acidity, and then pressurizing the water with carbon dioxide. The gas dissolves in the water, and a top-off fill of carbon dioxide is added to pressurize the siphon to approximately 120 pounds per square inch (830 kPa), some 30 to-[convert: unknown unit] higher than is present in fermenting champagne bottles.

In many modern restaurants and drinking establishments, soda water is manufactured on-site using devices known as carbonators. Carbonators use mechanical pumps to pump water into a pressurized chamber where it is combined with CO

2 from pressurized tanks at approximately 100 psi (690 kPa). The pressurized, carbonated water then flows to taps or to mixing heads where it is mixed with flavorings as it is dispensed.

Home

Carbonated water can be made at home by use of a readily available 1 L (1.1 US qt) rechargeable soda siphon, or seltzer bottle, and disposable carbon dioxide cartridges. One recipe is to chill filtered tap water in the fridge, optionally add one quarter to one half a level teaspoon of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) to the soda siphon, add the chilled water and add the carbon dioxide under pressure. A pH testing kit can be used to gauge the amount of sodium bicarbonate used to achieve the desired acidity. The siphon should be kept in the refrigerator to preserve carbonation of the contents. Many soda siphons are handsome objects in their own right, and are kept out for viewing on the drinks tray. Soda water made in this way tends not to be as 'gassy' as commercial soda water because water from the refrigerator is not chilled as much as possible, and the pressure of carbon dioxide is limited to that available from the cartridge rather than being at a higher pressure created by pumps in a commercial carbonation plant.

To reach the 'gassy,' fully carbonated level of commercial waters, the at-home enthusiast can either make or buy a carbonating system based on larger, refillable carbon dioxide canisters rather than small, disposable cartridges good for only one liter. Detailed and simple plans to build small in-home carbonating systems are freely available on the internet[4] [5] and can produce a liter of carbonated water for less than 5 US cents. Consumer priced carbonation machines targeted at the home market, such as Sodastream, have been successful. This is despite the higher cost related to the manufacturer-specific returnable pressurized carbon dioxide canisters (around 400 to 800 grams, enough for 40 to 80 liters of carbonated water). The commercial units are often sold with concentrated syrup flavoring for making soda.

Whether home made or store bought, soda water may be identical to plain carbonated water or it may contain a small amount[6] of table salt, sodium citrate, sodium bicarbonate, potassium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, potassium sulfate, or disodium phosphate, depending on the bottler. These additives are included to emulate the slightly salty taste of store-bought soda water. This process also occurs naturally to produce naturally carbonated mineral water, such as in Mihalkovo in the Bulgarian Rhodope Mountains, or in Medzitlija in Macedonia.

Soda siphons

The gas pressure in a siphon drives soda water up through a tube inside the siphon when a valve lever at the top is depressed. Careful use of the valve will prevent a surge of pressurized soda water being released into the drink, splashing forcibly upward. [citation needed].

Codd-neck bottles

A Codd-neck bottle was a special design to contain and store Carbonated Water at retail shops and restaurants in many parts of the world until recently. It is made of heavy glass. The gas pressure is retained by a marble that stays at the opening of the bottle. Once the marble is pressed down, the pressure gets released and marble falls down but within the neck of the bottle. Due to the risk of explosion and injuries from fragmented glass pieces, use of this type of bottle is not encouraged anymore in most countries.

In 1872, British soft drink maker Hiram Codd of Camberwell, London, designed and patented the bottle designed specifically for carbonated drinks. The Codd-neck bottle was designed and manufactured to enclose a marble and a rubber washer/gasket in the neck. The bottles were filled upside down, and pressure of the gas in the bottle forced the marble against the washer, sealing in the carbonation. The bottle was pinched into a special shape, as can be seen in the photo to the right, to provide a chamber into which the marble was pushed to open the bottle. This prevented the marble from blocking the neck as the drink was poured

Soon after its introduction, the bottle became extremely popular with the soft drink and brewing industries mainly in Europe, Asia and Australasia, though some alcohol drinkers disdained the use of the bottle. One etymology of the term codswallop originates from beer sold in Codd bottles, though this is generally dismissed as a folk etymology.[7]

The bottles were regularly produced for many decades, but gradually declined in usage. Since children smashed the bottles to retrieve the marbles, they are relatively rare and have become collector items; particularly in the UK. A cobalt coloured Codd bottle today fetches thousands of British pounds at auction[citation needed]. The Codd-neck design is still used for the Japanese soft drink Ramune and in the Indian drink called Banta.

Use

Carbonated water is often drunk plain or mixed with fruit juice. It is also mixed with alcoholic beverages to make cocktails, such as whisky and soda or Campari and soda. Flavored carbonated water is also commercially available. It differs from sodas in that it contains flavors (usually sour fruit flavors such as lemon, lime, cherry, orange, or raspberry) but no sweetener.

Carbonated water is a diluent. It works well in short drinks made with whiskey, brandy, and Campari and in long drinks such as those made with vermouth. Soda water may be used to dilute drinks based on cordials such as orange squash. Soda water is a necessary ingredient in many cocktails, where it is used to top-off the drink and provide a degree of 'fizz'. Adding soda water to 'short' drinks such as spirits dilutes them and makes them 'long'. One report states that the presence of carbon dioxide in a cocktail may accelerate the uptake of alcohol in the blood, making both the inebriation and recovery phases more rapid.[citation needed] The addition of carbonated water to dilute spirits was especially popular in hot climates and seen as a somewhat "British" habit. Adding soda water to quality Scotch whisky has been deprecated by whisky lovers, but was a popular lunchtime drink or early evening pre-dinner or pre-theater drink until the late part of the 20th century. Pre-filled glass soda-siphons were sold at many liquor stores: a deposit was charged on the siphon, to encourage the return of the relatively expensive siphon for re-filling. In 1965, the deposit on a single soda-siphon in England was 7/6d (seven shillings and six pence).

History

In 1767 Joseph Priestley invented carbonated water when he first discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide when he suspended a bowl of water above a beer vat at a local brewery in Leeds, England.[8] The air blanketing the fermenting beer—called 'fixed air'—was known to kill mice suspended in it. Priestley found water thus treated had a pleasant taste, and he offered it to friends as a cool, refreshing drink. In 1772, Priestley published a paper entitled "Impregnating Water with Fixed Air" in which he describes dripping "oil of vitriol" (sulfuric acid) onto chalk to produce carbon dioxide gas, and encouraging the gas to dissolve into an agitated bowl of water.[9]

In 1771 chemistry professor Torbern Bergman independently invented a similar process to make carbonated water. In poor health and frugal, he was trying to reproduce naturally-effervescent spring waters thought at the time to be beneficial to health.[citation needed]

Carbonated water was introduced in the latter part of the 18th century, and reached Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta), India in 1822.

In the late eighteenth century, J. J. Schweppe (1740–1821) developed a process to manufacture carbonated mineral water, based on the process discovered by Joseph Priestley, founding the Schweppes Company in Geneva in 1783. In 1792 he moved to London to develop the business there.

Ányos Jedlik (1800–95) invented consumable soda-water that is a popular drink today. He also built a carbonated water factory in Budapest, Hungary.[citation needed] The process he developed for getting the CO

2 into the water remains a mystery. After this invention, a Hungarian drink made of wine and soda water called "fröccs" (wine spritzers) was popular in Europe.

Since then, carbonated water is made by passing pressurized carbon dioxide through water. The pressure increases the solubility and allows more carbon dioxide to dissolve than would be possible under standard atmospheric pressure. When the bottle is opened, the pressure is released, allowing the gas to come out of the solution, forming the characteristic bubbles.

The soda siphon, or siphon — a glass or metal pressure vessel with a release valve and spout for dispensing pressurized soda water — was a common sight in bars and in early- to mid-20th century homes where it became a symbol of middle-class affluence.

Social popularity, decline, and renaissance

Carbonated water changed the way people drank. Instead of drinking spirits neat, soda water and carbonated soft drinks helped dilute alcohol, and made having a drink more socially acceptable. Popping into a friend's house for a "dash and a splash" — a whisky and soda — before going out to a social event was part of everyday life in Britain as late as 1965. [citation needed] Whisky and sodas can be seen in many British TV series and films from the 1960s and earlier and the soda siphon is ubiquitous in many movies made before 1970. Social drinking changed with the counter-culture movement of the 1970s, beginning the decline of soda water's popularity. Soda water's 'last hurrah' in Britain may have been the 1970s Sodastream, a home bottling kit which enabled the creation of sparkling beverages with fruit syrups and water.

The popularity of soda water has declined since the late 1980s as drinking habits changed and new bottled or canned beverages arrived. Soda siphons are still bought by the more traditional bar trade and are available at the bar in many upmarket establishments. In the UK there are now only two wholesalers of soda-water in traditional glass siphons, and an estimated market of around 120,000 siphons per year (2009). Worldwide, preferences are for beverages in recyclable plastic containers.

Home soda siphons and soda water are enjoying a renaissance in the 21st century as retro items become fashionable. Contemporary soda siphons are commonly made of aluminum, although glass and stainless steel siphons are available. The valve-heads of today are made of plastic, with metal valves, and replaceable o-ring seals. Older siphons are in demand on on-line auction sites. Carbonated water, without the acidity regulating addition of soda, is currently seen as fashionable although home production (see below) is mainly eschewed in favor of commercial products.

Health effects

Carbonated water is a negligible cause of dental erosion; also known as acid erosion. While the dissolution potential of sparkling water is greater than that of still water, it is quite low. In comparison, carbonated soft drinks cause tooth decay at a rate several hundred times that of sparkling water.[citation needed]

The de-gassing of carbonated water only slightly reduces its dissolution potential, which suggests that the addition of sugar to water, not the carbonation of water, is the main cause of tooth decay.[10]

Intake of carbonated beverages has not been associated with increased bone fracture risk in observational studies, and the net effect of carbonated beverage constituents on the amount of calcium in the body is negligible.[11] Carbonated water eases the symptoms of indigestion (dyspepsia) and constipation, according to a study in the European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.[12]

A 2004 article in the Journal of Nutrition found that fizzy waters with higher sodium levels reduced cholesterol levels and the risk of cardiovascular problems in postmenopausal women.[13]

A recent study has shown that sugar-sweetened and low-calorie sodas cause a higher risk of stroke.[14]

See also

- Carbonation

- Carbonic acid

- Effervescence

- Gasogene

- Premix and postmix

- Soda jerk

- Sodium bicarbonate

- Sodium carbonate

- Soft drink

- Tonic water

References

- ^ "Definition of seltzer - Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ "Carbon Dioxide in Water Equilibrium, Page 1". Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ James Monroe Jay, Martin J. Loessner, David Allen Golden (2005). Modern food microbiology. シュプリンガー・ジャパン株式会社. p. 210. ISBN 0-387-23180-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Making Carbonated Mineral Water". Milwaukee Makerspace. 2011-09-26.

- ^ "Home Carbonation System". Instructibles. 2007-07-15.

- ^ "Mineral Water Recipes". Scientific Psychic. 2010.

- ^ UK word origins

- ^ "Joseph Priestley - Discovery of Oxygen - Invention of Soda Water by Joseph Priestley". Inventors.about.com. 2009-09-16. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ^ Priestly, Joseph (1772). "Impregnating Water with Fixed Air, Page 7". Retrieved 2008-08-07. [dead link]

- ^ Parry J, Shaw L, Arnaud MJ, Smith AJ (2001). "Investigation of mineral waters and soft drinks in relation to dental erosion". Journal of oral rehab. 28 (8): 766–772. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00795.x. PMID 11556958.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burch, Druin (2006-02-02). "The sceptic". The Guardian. London.

- ^ http://bastyrcenter.org/content/view/899/

- ^ http://jn.nutrition.org/content/134/5/1058.full

- ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/04/120420123853.htm