Chester W. Nimitz

Chester W. Nimitz | |

|---|---|

Chester Nimitz as Fleet Admiral | |

| Birth name | Chester William Nimitz |

| Born | 24 February 1885 Fredericksburg, Texas |

| Died | 20 February 1966 (aged 80) Yerba Buena Island, California |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1905-1947 |

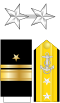

| Rank | |

| Service number | 5572 |

| Commands | USS Chicago (CA-14) USS Rigel (AR-11) USS Augusta (CA-31) Bureau of Navigation United States Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas Chief of Naval Operations |

| Battles / wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Navy Distinguished Service Medal (4) Army Distinguished Service Medal Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) Legion of Honor (France) |

| Other work | Regent of the University of California |

Fleet Admiral Chester William Nimitz, GCB, USN (February 24, 1885 – February 20, 1966) was a five-star admiral of the United States Navy. He held the dual command of Commander in Chief, United States Pacific Fleet (CinCPac), for U.S. naval forces and Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas (CinCPOA), for U.S. and Allied air, land, and sea forces during World War II.[1] He was the leading U.S. Navy authority on submarines, as well as Chief of the Navy's Bureau of Navigation in 1939. He served as Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) from 1945 until 1947. He was the United States' last surviving Fleet Admiral.

Early life

Chester W. Nimitz, a German Texan, was the son of Anna Josephine (Henke) and Chester Bernhard Nimitz. He was born 24 February 1885 in Fredericksburg, Texas,[2] where his house is now the Admiral Nimitz State Historic Site. His frail, rheumatic father died before he was born. He was significantly influenced by his grandfather, Charles Henry Nimitz, a former seaman in the German Merchant Marine, who taught him, "the sea - like life itself - is a stern taskmaster. The best way to get along with either is to learn all you can, then do your best and don't worry - especially about things over which you have no control."[3]

Originally, young Nimitz applied to West Point in hopes of becoming an Army officer, but there were no appointments available. His congressman, James L. Slayden, told him that he had one appointment available for the Navy and that he would award it to the best qualified candidate. Nimitz felt that this was his only opportunity for further education and spent extra time studying to earn the appointment. He was appointed to the United States Naval Academy from Texas's 12th congressional district in 1901, and he graduated with distinction on 30 January 1905, seventh in a class of 114.[4]

Military career

Early career

He joined the battleship Ohio at San Francisco, and cruised on her to the Far East. In September 1906, he was transferred to the cruiser Error: {{USS}} invalid control parameter: 2lll (help); and, on 31 January 1907, after the two years at sea as a warrant officer then required by law, he was commissioned as an Ensign. Remaining on Asiatic Station in 1907, he successively served on the gunboat Panay, destroyer Decatur, and cruiser Denver.

The destroyer USS Decatur (DD-5) ran aground on a sand bar in the Philippines on 7 July 1908 while under the command of Ensign Nimitz. The ship was pulled free the next day, and Nimitz was court-martialed, found guilty of neglect of duty, and issued a letter of reprimand.[5]

Nimitz returned to the United States onboard USS Ranger when that vessel was converted to a school ship, and in January 1909 began instruction in the First Submarine Flotilla. In May of that year he was given command of the flotilla, with additional duty in command of USS Plunger, later renamed A-1. He commanded USS Snapper (later renamed C-5) when that submarine was commissioned on 2 February 1910, and on 18 November 1910 assumed command of USS Narwhal (later renamed D-1). In the latter command he had additional duty from 10 October 1911, as Commander 3rd Submarine Division Atlantic Torpedo Fleet. In November 1911 he was ordered to the Boston Navy Yard, to assist in fitting out USS Skipjack and assumed command of that submarine, which had been renamed E-1, at her commissioning on 14 February 1912. On the monitor Tonopah on 20 March 1912, he rescued Fireman Second Class W. J. Walsh from drowning, receiving a Silver Lifesaving Medal for his action.[5]

After commanding the Atlantic Submarine Flotilla from May 1912 to March 1913, he supervised the building of diesel engines for the tanker Maumee, under construction at the New London Ship and Engine Company, Groton, Connecticut.

World War I

In the summer of 1913, Nimitz studied engines at the diesel engine plants in Nuremberg, Germany, and Ghent, Belgium. Returning to the New York Navy Yard, he became Executive and Engineer Officer of the fleet oiler Maumee on her commissioning, 23 October 1916. After the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917 Nimitz was on board the Maumee when it served as a refueling ship for the first squadron of U.S. Navy destroyers to cross the Atlantic to participate in the war. During this time Maumee conducted the first ever underway refuelings. On 10 August 1917, Nimitz became aide to Rear Admiral Samuel S. Robison, Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet (COMSUBLANT). On 6 February 1918, Nimitz was appointed Chief of Staff and was awarded a Letter of Commendation for meritorious service as COMSUBLANT's Chief of Staff. On 16 September, he reported to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, and on 25 October was given additional duty as Senior Member, Board of Submarine Design.

Between the wars

From May 1919 to June 1920 he served as executive officer of the battleship South Carolina. He then commanded the cruiser Chicago with additional duty in command of Submarine Division 14, based at Pearl Harbor. Returning to the mainland in the summer of 1922, he studied at the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, and in June 1923, became Aide and Assistant Chief of Staff to Commander Battle Fleet, and later to the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet. In August 1926 he went to the University of California, Berkeley to establish the Navy's first Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps unit.

Nimitz lost part of one finger in an accident with a diesel engine, only saving the rest of it when the machine jammed against his Annapolis ring.[6] Nimitz barked orders even through the excruciating pain.

In June 1929 he took command of Submarine Division 20. In June 1931 he assumed command of the destroyer tender Rigel and the destroyers out of commission at San Diego, California. In October 1933 he took command of the cruiser Augusta and deployed to the Far East, where in December Augusta became flagship of the Asiatic Fleet. In April 1935, he returned home for three years as Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, before becoming Commander, Cruiser Division 2, Battle Force. In September 1938 he took command of Battleship Division 1, Battle Force. On 15 June 1939 he was appointed Chief of the Bureau of Navigation.

World War II

Ten days after the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 he was selected Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet (CinCPAC), with the rank of Admiral, effective from 31 December. He took command in a ceremony on the top deck of the submarine USS Grayling. The change of command ceremony would normally taken place aboard a battleship, but every such ship in Pearl Harbor had been either sunk or damaged during the attack on 7 December. Assuming command at the most critical period of the war in the Pacific, Admiral Nimitz, despite the losses from the attack on Pearl Harbor and the shortage of ships, planes and supplies, successfully organized his forces to halt the Japanese advance.

On 24 March 1942, the newly-formed US-British Combined Chiefs of Staff issued a directive designating the Pacific theater an area of American strategic responsibility. Six days later the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) divided the theater into three areas: the Pacific Ocean Areas (POA), the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA, commanded by General Douglas MacArthur), and the South East Pacific Area. The JCS designated Nimitz as Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas CinCPOA, with operational control over all Allied units (air, land, and sea) in that area.

As rapidly as ships, men, and material became available, Nimitz shifted to the offensive and defeated the Japanese navy in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the pivotal Battle of Midway, and in the Solomon Islands Campaign.

By Act of Congress, approved 14 December 1944, the grade of Fleet Admiral of the United States Navy — the highest grade in the Navy — was established and the next day President of the United States Franklin Roosevelt appointed Admiral Nimitz to that rank. Nimitz took the oath of that office on 19 December 1944.

In the final phases in the war in the Pacific, he attacked the Mariana Islands, inflicting a decisive defeat on the Japanese Fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and capturing Saipan, Guam, and Tinian. His Fleet Forces isolated enemy-held bastions of the Central and Eastern Caroline Islands and secured in quick succession Peleliu, Angaur, and Ulithi. In the Philippines, his ships turned back powerful task forces of the Japanese Fleet, a historic victory in the multi-phased Battle for Leyte Gulf 24 to 26 October 1944. Fleet Admiral Nimitz culminated his long-range strategy by successful amphibious assaults on Iwo Jima and Okinawa. In addition, Nimitz also ordered the United States Army Air Forces to mine the Japanese ports and waterways by air with B-29 Superfortresses in a successful mission called Operation Starvation, which severely interrupted the Japanese logistics.

In January 1945, Nimitz moved the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet forward from Pearl Harbor to Guam for the remainder of the war. Mrs Nimitz remained in the continental United States for the duration of the war, and she did not join her husband in Hawaii or Guam.

On 2 September 1945 Nimitz signed for the United States when Japan formally surrendered on board the Missouri in Tokyo Bay. On 5 October 1945, which had been officially designated as "Nimitz Day" in Washington, D.C., Admiral Nimitz was personally presented a Gold Star for the third award of the Distinguished Service Medal by the President of the United States "for exceptionally meritorious service as Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, from June 1944 to August 1945...."

Post war

On 26 November 1945 his nomination as Chief of Naval Operations was confirmed by the US Senate, and on 15 December 1945 he relieved Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. He had assured the President that he was willing to serve as the CNO for one two-year term, but no longer. He tackled the difficult task of reducing the most powerful navy in the world to a fraction of its war-time strength, while establishing and overseeing active and reserve fleets with the strength and readiness required to support national policy.

At the same time, Nimitz endorsed an entirely new course for the U.S. Navy's future by way of supporting then-Captain Hyman G. Rickover's chain-of-command-circumventing proposal in 1947 to build USS Nautilus (SSN-571), the world's first nuclear-powered vessel.[7]

For the post-war trial of German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946, Admiral Nimitz furnished an affidavit in support of the practice of unrestricted submarine warfare, a practice that he himself had employed throughout the war in the Pacific. This evidence is widely credited as a reason why Dönitz was only sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment.[citation needed]

Inactive duty as a Fleet Admiral

On 15 December 1947, Nimitz retired from office of Chief of Naval Operations and received a third Gold Star in lieu of a fourth Navy Distinguished Service Medal. However, since the rank of Fleet Admiral is a lifetime appointment, he remained on active duty for the rest of his life, with full pay and benefits. He and his wife Catherine moved to Berkeley, California. After he suffered a serious fall in 1964, he and Catherine moved to US Naval quarters on Yerba Buena Island in the San Francisco Bay.

In San Francisco, he served in the mostly ceremonial post as a Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Navy in the Western Sea Frontier. After World War II, he worked to help restore goodwill with Japan by helping to raise funds for the restoration of the Japanese Imperial Navy battleship Mikasa, Admiral Heihachiro Togo's flagship at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. He was also suggested as a United Nations envoy to help mediate the Kashmir dispute, but due to the deterioration of relations between India and Pakistan, the mission did not take place.

Nimitz became a member of the Bohemian Club of San Francisco. In 1948, Nimitz sponsored a Bohemian dinner in honor of Army General Mark Clark, known for his campaigns in North Africa and Italy.[8]

Nimitz served as a regent of the University of California from 1948–1956, where he had formerly been a faculty member as a professor of Naval Science for the NROTC program. Nimitz was honored on 17 October 1964, by the University of California on Nimitz Day.

Personal life

Nimitz married Catherine Vance Freeman (22 March 1892 - 1 February 1979) on 9 April 1913, in Wollaston, Massachusetts.[5] He purchased a property built in 1930 for his daughter "Nancy" in Playa del Rey, CA on Rees Street at Delgany Ave.

Nimitz and his wife had four children:

- Catherine Vance "Kate" (b. 1914[9])

- Chester William "Chet", Jr. (1915–2002[9][10])

- Anna Elizabeth "Nancy" (1919–2003[11][12])

- Mary Manson (1931–2006[13][14])

Catherine Vance graduated from the University of California, Berkeley in 1934,[15] became a music librarian with the Washington D.C. Public Library,[16] and married U.S. Navy Commander James Thomas Lay (1909-2001[17]), from St. Clair, Missouri, in Chester and Catherine's suite at the Fairfax Hotel in Washington D.C. on 9 March 1945.[18] She had met Lay in the summer of 1934 while visiting her parents in Southeast Asia.[15]

Chester W. Nimitz, Jr., graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1936, and he served as a submariner in the Navy until his retirement in 1957, reaching the (post-retirement) rank of Rear Admiral; he served as chairman of PerkinElmer from 1969-1980.

Anna Elizabeth ("Nancy") Nimitz was an expert on the Soviet economy at the RAND Corporation from 1952 until her retirement in the 1980s.

Sister Mary Aquinas (Nimitz) became a sister in the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), working at Dominican University of California teaching biology for 16 years, academic dean for 11 years, acting president for 1 year, and vice president for institutional research for 13 years before becoming the university's Emergency Preparedness Coordinator. She held this job until her death 27 February 2006 when she lost her battle with cancer.

Nimitz suffered a stroke, complicated by pneumonia, in late 1965. In January 1966 he left the U.S. Naval Hospital (Oak Knoll) in Oakland to return home to his naval quarters. He died on the evening of 20 February 1966, at Quarters One on Yerba Buena Island in San Francisco Bay. He was buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California on 24 February 1966.[19][20][21][22]

Dates of rank

- Midshipman - January 1905

| Ensign | Lieutenant Junior Grade | Lieutenant | Lieutenant Commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 January 1907 | Never Held | 31 January 1910 | 29 August 1916 | 1 February 1918 | 2 June 1927 |

| Commodore | Rear Admiral | Vice Admiral | Admiral | Fleet Admiral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-7 | O-8 | O-9 | O-10 | O-11 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Never Held | 23 June 1938 | Never Held | 31 December 1941 | 19 December 1944 |

- Commodore - no longer a rank in the United States Navy, was previously reserved for wartime use and was not in use at the time of Nimitz's promotion to Flag Rank. Currently, a Captain who is promoted to pay grade O-7 becomes a Rear Admiral (Lower Half) and uses the abbreviated rank designation RDML as opposed to RADM, which designates a Rear Admiral (Upper Half), O-8. During Admiral Nimitz's service, the only rank existing among these was Rear Admiral, without distinction between upper and lower half.

- Fleet Admiral - rank made permanent in the United States Navy on 13 May 1946, a lifetime appointment.

At the time of Nimitz's promotion to Rear Admiral, the United States Navy did not maintain a one-star rank (Commodore). Nimitz was thus promoted directly from a Captain to a Rear Admiral. By Congressional Appointment, he skipped the rank of Vice Admiral and became an Admiral in December 1941.

Nimitz also never held the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade, as he was appointed a full Lieutenant after three years of service as an Ensign. For administrative reasons, Nimitz's naval record states that he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade and Lieutenant on the same day.

Decorations and awards

United States awards

Foreign awards

| United Kingdom - Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath | |

| United Kingdom - Pacific Star | |

| France - Légion d'honneur | |

| Philippines - Philippine Medal of Valor | |

| Philippines - Liberation Medal with one bronze service star | |

| Netherlands - Order of Orange-Nassau with Swords in the Degree of the Knight Grand Cross (Dutch: Orde van Oranje Nassau in de graad Ridder Grootkruis) | |

| Greece - Grand Cross of the Order of George I | |

| China - Grand Cordon of Pao Ting (Tripod) Special Class | |

| Guatemala - Cross of Military Merit First Class (Spanish: La Cruz de Merito Militar de Primera Clase) | |

| Cuba - Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos Manuel de Cespedes | |

| Argentina - Order of the Liberator (Spanish: Orden del Libertador San Martin) | |

| Ecuador - Star of Abdon Calderon (1st Class) | |

| Belgium - Grand Cross Order of the Crown (Belgium) with Palm (French: Grand Croix de l'ordre de la Couronne avec palme) | |

| Belgium - War Cross with Palm (French: Croix de Guerre Avec Palme) | |

| Italy - Knight of the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy (Cavaliere di Gran Croce) | |

| Brazil - Order of Naval Merit (Ordem do Merito Naval) |

Memorials and legacy

Besides the honor of a United States Great Americans series 50¢ postage stamp, the following institutions and locations have been named in honor of Nimitz:

- USS Nimitz, the first of her class of ten nuclear-powered supercarriers, which was commissioned in 1975 and remains in service

- Nimitz Foundation, established in 1970, which funds the National Museum of the Pacific War

- The Nimitz Freeway (Interstate 880) - from Oakland to San Jose, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Nimitz Glacier in Antarctica for his service during Operation Highjump as the CNO

- Nimitz Boulevard - a major thoroughfare in the Point Loma Neighborhood of San Diego

- Camp Nimitz, a recruit camp constructed in 1955 at the Naval Training Center, San Diego

- Nimitz Highway - state route 92 in Honolulu, Hawaii near the Honolulu airport

- The Nimitz Library, the main library at the U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland

- Callaghan Hall (the Naval and Air Force ROTC building at UC Berkeley) containing the Nimitz Library (was gutted by arson in 1985)

- The town of Nimitz in Summers County, West Virginia

- The summit on Guam where Chester Nimitz relocated his Pacific Fleet headquarters, and where the current Commander U.S. Naval Forces Marianas (ComNavMar) resides, is called Nimitz Hill

- Nimitz Park, a recreational area located at United States Fleet Activities Sasebo, Japan

- The Nimitz Trail in Tilden Park in Berkeley, California

- Main Gate at Pearl Harbor is called Nimitz Gate

- Admiral Nimitz Circle - located in Fair Park, Dallas, Texas

- Chester Nimitz Oriental Garden Waltz performed by Austin Lounge Lizards

- The Nimitz Building, Raytheon Corporation site headquarters, Portsmouth, Rhode Island

Schools

- Nimitz High School, Irving, Texas

- Nimitz High School (Harris County, Texas)

- Chester W. Nimitz Middle School, Huntington Park, California

- Nimitz Middle School (formerly a junior high), Odessa, Texas

- Nimitz Middle School in San Antonio, Texas

- Chester W. Nimitz Elementary School Honolulu, Hawaii

- Nimitz Middle School Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Nimitz Elementary School, Sunnyvale, California

- Nimitz Elementary School, Kerrville, Texas

See also

- Henry Arnold Karo -- see hand-written inscription on photo given to Adm. Karo

- Admiral of the Navy

- German American

Notes

- ^ Potter, E. B. (1976). Nimitz. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-87021-492-6.

- ^ Potter, p. 26.

- ^ John Woolley and Gerhard Peters. "Gerald R. Ford: Remarks at the U.S.S. Nimitz Commissioning Ceremony in Norfolk, Virginia". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- ^ "Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Biographical Sketch". The National Museum of the Pacific War. Archived from the original on 24 April 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- ^ Potter, p. 126.

- ^ Wallace, Robert (8 September 1958), "A Deluge of Honors For An Exasperating Admiral", LIFE, 45, No. 10, Time Inc.: 109, ISSN 0024-3019

- ^ Navy Department Library. "Documents relating to Admiral Nimitz's naval career." Retrieved on July 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Potter. - p.125.

- ^ SSDI. - SS#: 031-30-0451. - 17 February 1915—3 January 2002

- ^ Potter. - p.131.

- ^ SSDI. - SS#: 013-26-4596. - 13 September 1919—19 February 2004.

- ^ Potter. - p.150.

- ^ SSDI. - SS#: 562-02-6084. - 17 June 1931—27 February 2006

- ^ a b Potter. - p.158-159.

- ^ Potter. - p.165.

- ^ SSDI. - SS#: 224-52-2697. - 6 January 1909—13 September 2001.

- ^ Potter. - p.366.

- ^ Potter. - p.472.

- ^ "NIMITZ'S FUNERAL IS HELD ON COAST; Admiral Declined Arlington Burial to Lie With Men". The New York Times. United Press International. 25 February 1966.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lembke, Daryl E. (25 February 1966). "Adm. Nimitz Buried in Simple Rites". Los Angeles Times. p. 4.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Chester W. Nimitz at Find a Grave

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

References

- "Some Thoughts to Live By," Chester W. Nimitz with Andrew Hamilton, ISBN 0-686-24072-3, reprinted from Boys' Life Magazine, 1966.

- "Fleet Admiral Chester William Nimitz". Frequently Asked Questions. Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

Further reading

- Potter, E. B. Nimitz. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0-87021-492-9.

- Potter, E. B., and Chester W. Nimitz. Sea Power. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1960. ISBN 0-13-796870-1.

External links

- Mark J. Denger. "Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, A Five Star Submariner". Californians and the Military. California State Military Museum. Retrieved 3 December 2003.

- National Museum of the Pacific War

- USS Nimitz Association

- Nimitz-class Navy Ships at Federation of American Scientists

- Nimitz State Historic Site in Fredericksburg, Texas

- "The Navy‘s Part in the World War," (26 Nov 1945). A speech by Nimitz from the Commonwealth Club of California Records at the Hoover Institution Archives.

- Texas Navy hosted by The Portal to Texas History. A survey of the Texas Navy during the Texas Revolution and the Republic Era. Includes maps, sketches, a list of ships of the Texas Navy, and a chronology. Also includes photographs of 20th century U.S. Navy ships named after Texans or Texas locations. See photos of Chester Nimitz and the Nimitz hotel.

- The short film Big Picture: The Admiral Chester Nimitz Story is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Guide to the Chester W. Nimitz Papers, 1941-1966 MS 236 held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy

- Use dmy dates from August 2010

- 1885 births

- 1966 deaths

- American 5 star officers

- American people of German descent

- Chiefs of Naval Operations

- Deaths from stroke

- Germans in Texas

- Grand Crosses of the Order of George I

- High Commissioners of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

- Naval War College alumni

- People from Fredericksburg, Texas

- People from Gillespie County, Texas

- People from Kerrville, Texas

- People from the Texas Hill Country

- United States Naval Academy alumni

- United States Navy admirals

- United States Navy World War II admirals

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Crown (Belgium)

- Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (Belgium)

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

- Recipients of the Order of Naval Merit (Brazil)

- Recipients of the Order of the Liberator General San Martin

- Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Tripod

- Recipients of the Philippine Medal of Valor