Conlon Nancarrow

Conlon Nancarrow | |

|---|---|

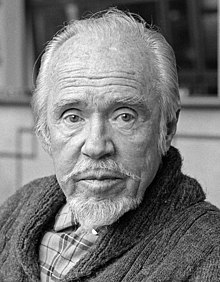

Nancarrow in 1987 | |

| Born | Samuel Conlon Nancarrow October 27, 1912 |

| Died | August 10, 1997 (aged 84) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican, American |

| Occupation | Composer |

| Known for | Studies for Player Piano |

Samuel Conlon Nancarrow (/nænˈkæroʊ/;[1] October 27, 1912 – August 10, 1997) was an American-Mexican composer who lived and worked in Mexico for most of his life. Nancarrow is best remembered for his Studies for Player Piano, being one of the first composers to use auto-playing musical instruments, realizing their potential to play far beyond human performance ability. He lived most of his life in relative isolation and did not become widely known until the 1980s.

Biography[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2012) |

Early years[edit]

Nancarrow was born in Texarkana, Arkansas. He played trumpet in a jazz band in his youth before studying music first in Cincinnati, Ohio, and later in Boston, Massachusetts, with Roger Sessions, Walter Piston and Nicolas Slonimsky.[2] He met Arnold Schoenberg during that composer's brief stay in Boston in 1933.[3]

In Boston, Nancarrow joined the Communist Party. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, he traveled to Spain to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in fighting against Francisco Franco. He was interned by the French at the Gurs internment camp in 1939.[4][5] Upon his return to the United States in 1939, he learned that his Brigade colleagues were finding it difficult to renew their U.S. passports. After spending some time in New York City, Nancarrow moved in 1940 to Mexico, in order to escape similar harassment.[2]

He visited the United States briefly in 1947 and became a Mexican citizen in 1956.[2][5] His next appearance in the U.S. was in San Francisco for the New Music America festival in 1981. He traveled regularly in the following years[5] and lived in the current Casa Estudio Conlon Nancarrow (designed by Juan O'Gorman) at Las Águilas, Mexico City, until his death at 84. He was friends with some Mexican composers but was largely unknown in the local music establishment.

As a composer[edit]

It was in Mexico that Nancarrow did the work for which he is best known today. He had already written some music in the United States, but the extreme technical demands of his compositions required great proficiency in the performer, which resulted in there being only rare satisfactory performances. That situation did not improve in Mexico's musical environment. There being few musicians available who could perform his works, his need to find an alternative way of having his pieces performed became pressing. Taking a suggestion from Henry Cowell's book New Musical Resources, which he bought in New York in 1939, Nancarrow found the answer in the player piano, with its ability to produce extremely complex rhythmic patterns at a speed far beyond the abilities of humans.

Cowell had suggested that just as there is a scale of pitch frequencies, there might also be a scale of tempi. Nancarrow undertook to create music which would superimpose tempi in cogent pieces and, by his twenty-first composition for player piano, he had begun "sliding" (increasing and decreasing) tempi within strata. (See William Duckworth, Talking Music.) Nancarrow later said he had been interested in exploring electronic resources but that the piano rolls ultimately gave him more temporal control over his music.[6]

Temporarily buoyed by an inheritance, Nancarrow traveled to New York City in 1947 and bought a custom-built manual punching machine to enable him to punch the piano rolls. The machine was an adaptation of one used in the commercial production of rolls, and using it was very hard work and very slow. He also adapted the player pianos, increasing their dynamic range by tinkering with their mechanism and covering the hammers with leather (in one player piano) and metal (in the other) so as to produce a more percussive sound. On this trip to New York, he met Cowell and heard a performance of John Cage's Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano (also influenced by Cowell's aesthetics), which would later lead to Nancarrow's modestly experimenting with prepared piano in his Study No. 30.

Nancarrow's first pieces combined the harmonic language and melodic motifs of early jazz pianists like Art Tatum with extraordinarily complicated metrical schemes. The first five rolls he made are called the Boogie-Woogie Suite (later assigned the name Study No. 3 a-e). His later works were abstract, with no obvious references to any music apart from his own.

Many of these later pieces (which he generally called studies) are canons in augmentation or diminution (i.e. prolation canons). While most canons using this device, such as those by Johann Sebastian Bach, have the tempos of the various parts in quite simple ratios, such as 2:1, Nancarrow's canons are in far more complicated ratios. The Study No. 40, for example, has its parts in the ratio e:pi, while the Study No. 37 has twelve individual melodic lines, each one moving at a different tempo.

Having spent many years in obscurity, Nancarrow benefited from the 1969 release of an entire album of his work by Columbia Records as part of a brief flirtation of the label's classical division with modern avant-garde music.

Later life[edit]

In 1976–77, Peter Garland began publishing Nancarrow's scores in his Soundings journal, and Charles Amirkhanian began releasing recordings of the player piano works on the 1750 Arch label. Thus, at age 65, Nancarrow started coming to wide public attention. He became better known in the 1980s and was lauded by many, including György Ligeti, as one of the most significant composers of the century.

In 1982, he received a MacArthur Award which paid him $300,000 over 5 years. This increased interest in his work prompted him to write for conventional instruments, and he composed several works for small ensembles.

Nancarrow was married to Annette Margolis (grandmother of the writer Bret Stephens).[7][8][9]

On March 2, 1971, Nancarrow married Yoko Sugiura Yamamoto in Mexico City.

Nancarrow died in 1997[2] in Mexico City. The complete contents of his studio, including the player piano rolls, the instruments, the libraries, and other documents and objects, are now in the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel.

Reception[edit]

The composer György Ligeti described the music of Conlon Nancarrow as "the greatest discovery since Webern and Ives ... something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, perfectly constructed, but at the same time emotional ... for me it's the best music of any composer living today."[10]

Legacy[edit]

In 1995, the composer and critic Kyle Gann published a full-length study of Nancarrow's output, The Music of Conlon Nancarrow (Cambridge University Press, 1995, 303 pp.). Jürgen Hocker, another Nancarrow specialist, published Begegnungen mit Nancarrow (neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Schott Musik International, Mainz 2002, 284 pp.)

Some of Nancarrow's studies for player piano have been arranged for musicians to play on other instruments.

The German musician Wolfgang Heisig has long given live performances of Nancarrow's rolls, as did Jürgen Hocker until his death in 2012. Both used acoustical instruments similar to Nancarrow's.

Other performers of Nancarrow's works (often in arrangement for live musicians) include Thomas Adès, Alarm Will Sound, and ensemble Calefax from the Netherlands who also recorded the Studies for player piano, hailed as 'Best CD of 2009' by Dutch newspaper Het Parool.[11] American clarinetist and composer Evan Ziporyn has adapted a number of Nancarrow's player piano studies for the Bang on a Can All-Stars to perform live.[12]

Nancarrow's work has also been seen as the analog predecessor to Black MIDI, a genre of electronic music.[13]

Nancarrow was an early inspiration to the American computer scientist and composer Jaron Lanier.[14]

In 2012, Other Minds in collaboration with Cal Performances and the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive held a three-day festival of films and music celebrating Nancarrow's centennial in Berkeley, California.[15]

Recordings[edit]

Columbia Records MS 7222 (released 1969, deleted 1973) Studies Nos. 2, 7, 8, 10, 12, 15, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 33. Recorded at the composer's studio under his supervision. Includes the original version of Study #10.

New World Records "Sound Forms for Piano" (LP released 1976, CD released 1995) includes Studies Nos. 1, 27 and 36, which were recorded at the composer's studio in 1973 using his two Ampico player pianos, and recording equipment described as "antiquated but well maintained".

1750 Arch Records (recorded 1977) produced by Charles Amirkhanian and originally released on 4 LPs between 1977 and 1984. These are the only available recordings using Nancarrow's original instruments: two 1927 Ampico player pianos, one with metal-covered felt hammers and the other with leather strips on the hammers, representing the most faithful reproduction of what Nancarrow heard in his own studio.

Nancarrow's entire output for player piano has been recorded and released on the German Wergo label in 1989–91.

In 1993, BMG released a CD (090262611802) of works by Nancarrow (Studies for Player Piano, Tango, Toccata, Piece No.2 for Small Orchestra, Trio, Sarabande & Scherzo) played by Ensemble Modern, conducted by Ingo Metzmacher.

In March 2000, Other Minds Records released a CD of largely forgotten works by Nancarrow, Lost Works, Last Works, including previously unrecorded works such as Piece for Tape and Nancarrow's own recording of his study for prepared player piano, in addition to an interview with the composer himself.[16]

In July 2008, Other Minds Records released a newly remastered version of the 1750 Arch Records recordings on 4 CDs.[17] The 4-CD set includes a 52-page booklet with the original liner notes by James Tenney, an essay by producer Charles Amirkhanian and 24 illustrations.

A recording of "Study #7", arranged for orchestra, was performed by the London Sinfonietta and included on their 2006 CD Warp Works & Twentieth Century Masters.

An arrangement of "Player Piano Study #6" for piano and marimba was recorded by Alan Feinberg and Daniel Druckman on Feinberg's 1994 album Fascinating Rhythm.

List of works[edit]

- Note: For a detailed listing of the player piano studies, see: Kyle Gann's Conlon Nancarrow: Annotated List of Works.[18]

- Note: For an updated list (Jan 2008) of ALL the works, arrangements and editions included, see: Monika Fürst-Heidtmann "Dated and commented list of the works, premieres and arrangements of the music of Conlon Nancarrow".[19]

Player piano[edit]

- Studies #1–30, (1948–1960) (#30 for prepared player piano)

- Studies #31–37, #40–51, (1965–1992) (#38 and #39 renumbered as #43 and #48)

- For Yoko (1990)

- Contraption #1 for computer-driven prepared piano (1993)

Piano[edit]

- Blues (1935)

- Prelude (1935)

- Sonatina (1941)

- 3 Two-Part Studies (1940s)

- Tango? (1983)

- 3 Canons for Ursula (1989)

Chamber[edit]

- Sarabande and Scherzo for oboe, bassoon and piano (1930)

- Toccata for violin and piano (1935)

- Septet (1940)

- Trio for clarinet, bassoon and piano, #1, (1942)

- String Quartet #1 (1945)

- String Quartet #2 (late 1940s) incomplete

- String Quartet #3 (1987)

- Trio for oboe, bassoon and piano, #2 (1991)

- Player Piano Study #34 arranged for string trio

Orchestral[edit]

- Piece #1 for small orchestra (1943)

- Piece #2 for small orchestra (1985) [20]

- Studio for Orchestra, canon 4:5:6, (1990–91), Original C.N. orchestration: 3fl., 3ob., 3Bb cl., 2bsn., 3 F.Hrn., 3 trp., 3tbn., Tuba, 2Vib., Xil., Mar., one computer-controlled piano, Pf., 6 vln., 2vc., 3 db[further explanation needed]. In two movements. Based on the Study 49 a-c.[21]

References[edit]

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c d Kozinn, Allan (12 August 1997). "Conlon Nancarrow Dies at 84; Composed for the Player Piano". New York Times. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ Gann, Kyle (2006). The Music of Conlon Nancarrow, p.38. ISBN 978-0521028073.

- ^ Ghent, Janet Silver (12 May 2011). "Magnified musically: Obscure Holocaust prison camp inspires Stanford's artist-in-residence". J. Jweekly. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Hocker, Jürgen. "Chronology: Nancarrows Life and Work*1912–1997". Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ Conlon Nancarrow with Charles Amirkhanian (April 28, 1977). "An Interview with Conlon Nancarrow". Other Minds Archives. Retrieved Feb 15, 2024.

- ^ "Conlon Nancarrow: A Chronology". Kylegann.com. 1997-08-10. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ^ "Charles J. Stephens". Vvsaz.org. 2011-12-08. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ^ "Annettes Memories relating to her life with Conlon". nancarrow.de. 1991. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Quoted in Kyle Gann. The Music of Conlon Nancarrow, p.2.

- ^ "Calefax". Calefax.nl. Archived from the original on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ^ "Program Notes". Bangonacan.org. Archived from the original on 2012-03-07.

- ^ Reising, Sam (April 15, 2015). "The Opposite of Brain Candy—Decoding Black MIDI". NewMusicBox. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Lanier, Jaron (2013). Who Owns the Future?. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 159–162. ISBN 9781451654974.

- ^ "Nancarrow at 100: A Centennial Celebration". Other Minds Archives. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Conlon Nancarrow: Lost Works, Last Works". Otherminds.org. Retrieved 2023-05-26.

- ^ "Conlon Nancarrow's Studies for Player Piano". Otherminds.org. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ^ "Conlon Nancarrow: List of Works". Kylegann.com. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ^ Conlon Nancarrow: list of Works by Monika Fürst-Heidtmann

- ^ List of works from Gann, Kyle. "Nancarrow, (Samuel) Conlon" at Grove Music Online Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Recording of the piece". Personal archive, Carlos Sandoval. carlos-sandoval.de. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

Further reading[edit]

- Zimmerman, Walter, Desert Plants – Conversations with 23 American Musicians, Berlin: Beginner Press in cooperation with Mode Records, 2020 (originally published in 1976 by A.R.C., Vancouver). The 2020 edition includes a cd featuring the original interview recordings with Larry Austin, Robert Ashley, Jim Burton, John Cage, Philip Corner, Morton Feldman, Philip Glass, Joan La Barbara, Garrett List, Alvin Lucier, John McGuire, Charles Morrow, J.B. Floyd (on Conlon Nancarrow), Pauline Oliveros, Charlemagne Palestine, Ben Johnston (on Harry Partch), Steve Reich, David Rosenboom, Frederic Rzewski, Richard Teitelbaum, James Tenney, Christian Wolff, and La Monte Young.

External links[edit]

- Portrait, interviews and complete annotated list of Nancarrow's works, including first performances and arrangements compiled by Monika Fürst-Heidtmann

- CompositionToday - Conlon Nancarrow article and review of works

- Composer & musicologist Kyle Gann's Nancarrow Page Gann, author of "The Music of Conlon Nancarrow", is one of the current authorities on the composer's work.

- Hocker's Life and Work of Conlon Nancarrow. Invaluable information, photos and letters, in German By Jürgen Hocker.

- Carlos Sandoval's site Specific information on Nancarrow's studio, music library (databased) and other very specific issues. Carlos Sandoval was Nancarrow's assistant.

- Children of Nancarrow, a documentary about the composers who have been influenced by Nancarrow

- Conlon Nancarrow interview by Bruce Duffie (1987)

- Writings on Nancarrow

- "Conlon Nancarrow (biography, works, resources)" (in French and English). IRCAM.

- Links to Nancarrow resources, centennial symposium, and concerts

Listening[edit]

- Charles Amirkhanian interviews Conlon Nancarrow by telephone from his home in Mexico City 1991

- Conlon Nancarrow on KPFA's Ode To Gravity series from 1987, including interviews from Mexico City and New York by Charles Amirkhanian, recorded in 1977

- A Sense of Place: The Life and Work of Conlon Nancarrow (Helen Borten, writer/producer/narrator; 28 January 1994)

- Conlon Nancarrow: Otherworldly Compositions for Player Piano a radio article produced by Minnesota Public Radio a few months after Nancarrow's death; several works are excerpted in the article itself, and several others can be found on the accompanying page

- 1912 births

- 1997 deaths

- People from Texarkana, Arkansas

- Members of the Communist Party USA

- American male classical composers

- American classical composers

- 20th-century classical composers

- Abraham Lincoln Brigade members

- American emigrants to Mexico

- American people of Cornish descent

- MacArthur Fellows

- Mexican communists

- Mexican male classical composers

- Mexican classical composers

- Mexican people of Cornish descent

- Naturalized citizens of Mexico

- Musicians from Mexico City

- Pupils of Roger Sessions

- Pupils of Walter Piston

- 20th-century American composers

- Gurs internment camp survivors

- 20th-century American male musicians