Early Modern Irish

| Early Modern Irish | |

|---|---|

| Early Modern Gaelic | |

| Gaoidhealg | |

| |

| Native to | Scotland, Ireland |

| Era | 13th to 18th century |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ghc |

| Glottolog | hibe1235 |

Early Modern Irish (Irish: Gaeilge Chlasaiceach, lit. 'Classical Irish') represented a transition between Middle Irish and Modern Irish.[1] Its literary form, Classical Gaelic, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.[2][3]

External history

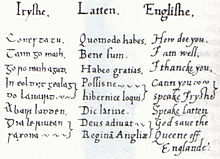

The Tudor dynasty sought to subdue its Irish citizens. The Tudor rulers attempted to do this by restricting the use of the Irish language while simultaneously promoting the use of the English language. English expansion in Ireland, outside of the Pale, was attempted under Mary I, but ended with poor results.[4] Queen Elizabeth I however encouraged the use of Irish even in the Pale with a view to promoting the reformed religion. She was proficient in several languages and is reported to have expressed a desire to understand Irish, so a primer was prepared on her behalf by Christopher Nugent, 6th Baron Delvin.

Grammar

The grammar of Early Modern Irish is laid out in a series of grammatical tracts written by native speakers and intended to teach the most cultivated form of the language to student bards, lawyers, doctors, administrators, monks, and so on in Ireland and Scotland. The tracts were edited and published by Osborn Bergin as a supplement to Ériu between 1916 and 1955.[5]

Neuter nouns still trigger eclipsis of a following complement, as they did in Middle Irish, but less consistently. The distinction between preposition + accusative to show motion toward a goal (e.g. san gcath "into the battle") and preposition + dative to show non–goal-oriented location (e.g. san chath "in the battle") is lost during this period, as is the distinction between nominative and accusative case in nouns.

Verb endings are also in transition.[1] The ending -ann (which spread from conjuct forms of Old Irish n-stem verbs like benaid, ·ben "(he) hits, strikes"), today the usual 3rd person ending in the present tense, was originally just an alternative ending found only in verbs in dependent position, i.e. after particles such as the negative, but it started to appear in independent forms in 15th century prose and was common by 17th century. Thus Classical Gaelic originally had molaidh "[he] praises" versus ní mhol or ní mholann "[he] does not praise", whereas later Classical Gaelic and Modern Irish have molann sé and ní mholann sé.[3] This innovation was not followed in Scottish Gaelic, where the ending -ann has never spread, but the present and future tenses were merged: glacaidh e "he will grasp" but cha ghlac e "he will not grasp".[6]

Literature

The first book printed in any Goidelic language was published in 1567 in Edinburgh, a translation of John Knox's 'Liturgy' by Séon Carsuel, Bishop of the Isles. He used a slightly modified form of the Classical Gaelic and also used the Roman script. In 1571, the first book in Irish to be printed in Ireland was a Protestant 'catechism', containing a guide to spelling and sounds in Irish.[7] It was written by John Kearney, treasurer of St. Patrick's Cathedral. The type used was adapted to what has become known as the Irish script. This was published in 1602-3 by the printer Francke. The Church of Ireland (a member of the Anglican communion) undertook the first publication of Scripture in Irish. The first Irish translation of the New Testament was begun by Nicholas Walsh, Bishop of Ossory, who worked on it until his murder in 1585. The work was continued by John Kearny, his assistant, and Dr. Nehemiah Donellan, Archbishop of Tuam, and it was finally completed by William Daniel (Uilliam Ó Domhnaill), Archbishop of Tuam in succession to Donellan. Their work was printed in 1602. The work of translating the Old Testament was undertaken by William Bedel (1571–1642), Bishop of Kilmore, who completed his translation within the reign of Charles the First, however it was not published until 1680, in a revised version by Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713), Archbishop of Dublin. William Bedell had undertaken a translation of the Book of Common Prayer in 1606. An Irish translation of the revised prayer book of 1662 was effected by John Richardson (1664–1747) and published in 1712.

Encoding

ISO 639-3 gives the name "Hiberno-Scottish Gaelic" (and the code ghc) to cover both Classical Gaelic and Early Modern Irish.

See also

References

- ^ a b Bergin, Osborn (1930). "Language". Stories from Keating's History of Ireland (3rd ed.). Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.

- ^ Mac Eoin, Gearóid (1993). "Irish". In Martin J. Ball (ed.). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 101–44. ISBN 978-0-415-01035-1.

- ^ a b McManus, Damian (1994). "An Nua-Ghaeilge Chlasaiceach". In K. McCone; D. McManus; C. Ó Háinle; N. Williams; L. Breatnach (eds.). Stair na Gaeilge: in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta (in Irish). Maynooth: Department of Old Irish, St. Patrick's College. pp. 335–445. ISBN 978-0-901519-90-0.

- ^ Hindley, Reg. 1990. The Death of the Irish language: A qualified obituary London: Routledge, p. 6.

- ^ Rolf Baumgarten and Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh, 2004. Electronic Bibliography of Irish Linguistics and Literature 1942–71. Accessed 27 December 2007.

- ^ Calder, George (1923). A Gaelic Grammar. Glasgow: MacLaren & Sons. p. 223.

- ^ T. W. Moody; F. X. Martin; F. J. Byrne (12 March 2009). "The Irish Language in the Early Modern Period". A New History of Ireland, Volume III: Early Modern Ireland 1534-1691. Oxford University Press. p. 511. ISBN 9780199562527. Retrieved 6 February 2015.