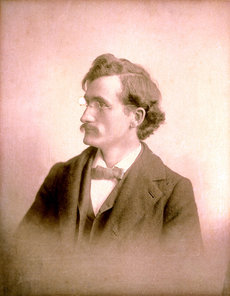

Liberty Hyde Bailey

Liberty Hyde Bailey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 15, 1858 |

| Died | December 25, 1954 (aged 96) |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | Michigan Agricultural College |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | botanist |

| Institutions | Cornell University |

Liberty Hyde Bailey (March 15, 1858 – December 25, 1954) was an American horticulturist, botanist and cofounder of the American Society for Horticultural Science.[1]: 10–15

Biography

Born in South Haven, Michigan, as the third son of farmers Liberty Hyde Bailey Sr. and Sarah Harrison Bailey, Bailey entered the Michigan Agricultural College (MAC, now Michigan State University) in 1878 and graduated in 1882. The next year, he became assistant to the renowned botanist Asa Gray, of Harvard University. This was arranged by a professor at MAC, William James Beal.[2] Bailey spent two years with Gray as his herbarium assistant.[3][4] The same year, he married Annette Smith, the daughter of a Michigan cattle breeder, whom he met at the Michigan Agricultural College. They had two daughters, Sara May, born in 1887, and Ethel Zoe, born in 1889.

In 1885, he moved to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where he in 1888 assumed the chair of Practical and Experimental Horticulture. He was elected an Associate Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1900.[5] He founded the College of Agriculture, and in 1904 he was able to secure public funding. He was dean of what was then known as New York State College of Agriculture from 1903-1913. In 1908, he was appointed Chairman of The National Commission on Country Life by president Theodore Roosevelt. Its 1909 Report called for rebuilding a great agricultural civilization in America. In 1913, he retired to become a private scholar and devote more time to social and political issues. In 1917 he was elected a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences.[6]

He edited The Cyclopedia of American Agriculture (1907–09), the Cyclopedia of American Horticulture (1900–02) (continued as the Standard Cyclopedia Of Horticulture (1916–1919)[7]) and the Rural Science, Rural Textbook, Gardencraft, and Young Folks Library series of manuals. He was the founding editor of the journals Country Life in America and the Cornell Countryman. He dominated the field of horticultural literature, writing some sixty-five books, which together sold more than a million copies, including scientific works, efforts to explain botany to laypeople, a collection of poetry; edited more than a hundred books by other authors and published at least 1,300 articles and over 100 papers in pure taxonomy.[8] He also coined the words "cultivar",[9] "cultigen",[10] and "indigen". His most significant and lasting contributions were in the botanical study of cultivated plants.

Rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's work

Bailey was one of the first to recognize the overall importance of Gregor Mendel's work. He cited Mendel's 1865 and 1869 papers in the bibliography that accompanied his 1892 paper, "Cross Breeding and Hybridizing." Mendel is mentioned again in the 1895 edition of Bailey's "Plant Breeding."[11][12][13]

Agrarian ideology

Bailey represented an agrarianism that stood in the tradition of Thomas Jefferson. He had a vision of suffusing all higher education, including horticulture, with a spirit of public work and integrating "expert knowledge" into a broader context of democratic community action.[14] As a leader of the Country Life Movement, he strove to preserve the American rural civilization, which he thought was a vital and wholesome alternative to the impersonal and corrupting city life. In contrast to other progressive thinkers at the time, he endorsed the family, which, he recognized, played a unique role in socialization. Especially the family farm had a benign influence as a natural cooperative unit where everybody had real duties and responsibilities. The independence it fostered made farmers "a natural correction against organization men, habitual reformers, and extremists". It was necessary to uphold fertility in order to maintain the welfare of future generations.[15]

According to Bailey, the American rural population, however, was backward, ignorant and saddled with inadequate institutions. The key to his reform program was guidance by an educated elite toward a new social order. The Extension System was partly pioneered by Bailey. The grander design of a new rural social structure needed a philosophical vision that could inspire and motivate. For this purpose, he wrote Mother Earth, a "powerful testament to Nature as God and to the farmer as acolyte and collaborator in the process of ongoing creation". It conformed largely to the Freemason creed that Bailey had been brought up with, and it was not explicit in demanding that traditional Christian dogma be discarded.[15]

Bailey's real legacy was, according to Allan C. Carlson, the themes and direction that he gave the new agrarian movement, ideas very different from previous agrarian thought. He saw technological innovation as friendly to the family farm and inevitably resulting in decentralization. He was scornful of the actual forms of peasant life and wanted to transform it by cutting the farmers loose from "the slavery of old restraints". Parochial and communal social groups should be broken down and replaced by "inter–neighborhood" and "inter–community" groups, while new leaders would be called in "who will promote inclusive rather than exclusive sociability." Bailey and his followers held a quasi–religious faith in education by enlightened experts, which meant suppression of inherited ways and substitution by progressive ways. It was accompanied by a corresponding hostility to traditional religion.[15]

Bailey's simultaneous embrace of the rural civilization and of technological progress had been based on a denial of the possibility of overproduction of farm products. When that became a reality in the 1920s, he turned to a "new economics" that would give farmers special treatment. Finally, after desperately toying with Communism, he had to choose between fewer farmers and farm families and restraint on technology or production. He chose to preserve technology rather than the family farms. After this, he retreated from the Country Life movement into scientific study.[15]

Bailey's influence on modern American Agrarianism remains determinative. The inherent contradictions of his ideas have been equally persistent: the tension between real farmers and rural people and the Country Life campaign; difficulties to understand the operative economic forces; the reliance on state schools to safeguard family farms; and hostility to traditional Christian faith.[15]

Tribute to Bailey

Cornell has memorialized Bailey by dedicating Bailey Hall in his honor. Since 1958 the American Horticultural Society has issued the annual Liberty Hyde Bailey Award.[16] A residence hall in Brody Complex at Michigan State University, and an elementary school in East Lansing, Michigan, were also named after him.

Bailey's publisher was George Platt Brett, Sr. of Macmillan Publishers (United States).[17]

Bailey is credited with being instrumental in starting agricultural extension services, the 4-H movement, the nature study movement, parcel post and rural electrification. He was considered the father of rural sociology and rural journalism.

About 140 years after his birth, the Liberty Hyde Bailey Scholars Program was created at Michigan State University, the institution of higher learning where Bailey began his career. The Bailey Scholars Program incorporates L.H. Bailey's love of learning and expressive learning styles to provide a space for students to become educated in fields that interest them.

Some selected works

|

|

Selected articles

- Bailey, L.H. - Canna x generalis. Hortus, 118 (1930); cf. Standley & Steyerm. in Fieldiana, Bot., xxiv. III.204 (1952).

- Bailey, L.H. - Canna x orchiodes. Gentes Herb. (Ithaca), 1 (3): 120 (1923).

See also

References

- ^ Makers of American Botany, Harry Baker Humphrey, Ronald Press Company, Library of Congress Card Number 61-18435

- ^ Dupree, A. Hunter (1988). Asa Gray, American Botanist, Friend of Darwin. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 384–385, 388. ISBN 978-0-801-83741-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Liberty Hyde Bailey Jr. (1858-1954) Papers". Harvard University Herbaria. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Liberty Hyde Bailey Jr. (1858-1954) Papers". Harvard University Herbaria. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter B" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Banks, Harlan P. (1994). "Liberty Hyde Bailey 1858—1954" (PDF). Biographical Memoirs. 64. United States National Academy of Sciences.

- ^ a b Bailey 1919.

- ^ "Liberty Hyde Bailey Writings". Cornell University Library. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Bailey, L.H. (1923). Various cultigens, and transfers in nomenclature. Gentes Herb. 1: 113-136

- ^ Bailey, L.H. (1918). The indigen and the cultigen. Science ser. 2, 47: 306-308.

- ^ "The Role of Liberty Hyde Bailey and Hugo de Vries in the Rediscovery of Mendelism," Conway Zirkle, Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Autumn, 1968), pp. 205-218. Here is an excerpt: "De Vries as we have noted, gave three different accounts, and this leads us to Liberty Hyde Bailey (1858-1954). In a letter to Bailey, de Vries stated that he was led to Mendel's work by an item in a bibliography that Bailey had published in 1892. Bailey inserted an excerpt from this letter in a footnote in the later editions of his book, Plant Breeding, a very successful book that went through several editions. De Vries wrote (from the Fourth Edition, 1906, p. 155): Many years ago you had the kindness to send me your article on Cross Breeding and Hybridization of 1892; and I hope it will interest you to know that it was by means of your bibliography therein that I learned some years afterwards of the existence of Mendel's papers, which now are coming to so high credit. Without your aid I fear I should not have found them at all. Some years later (1924), de Vries gave another and different account in a letter he wrote to Roberts....."

- ^ Conway Zirkle: "The role of Liberty Hyde Bailey and Hugo de Vries in the rediscovery of Mendelism," The Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 1, No. 2 / September, 1968.

- ^ "L.H. Bailey's citations to Gregor Mendel" in: Michael H. MacRoberts, The Journal of Heredity 1984:75(6):500-501. Here's part of the abstract: "L. H. Bailey cited Mendel's 1865 and 1869 papers in the bibliography that accompanied his 1892 paper, Cross-Breeding and Hybridizing, and Mendel is mentioned once in the 1895 edition of Bailey's Plant-Breeding. Bailey also saw a reference to Mendel's 1865 paper in Jackson's Guide to the Literature of Botany. Bailey's 1895 mention of Mendel occurs in a passage he translated from Focke's Die Pflanzen-Mischlinge."

- ^ Stephen L. Elkin, Karol Edward Sołtan: Citizen competence and democratic institutions p. 272. Penn State Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-271-01816-4

- ^ a b c d e Allan C Carlson: The New Agrarian Mind Chapter 1 "Toward a New Rural Civilization: Liberty Hyde Bailey"

- ^ "Previous Winners: Honoring Horticultural Heroes". Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Biographic Memoirs V. 64. p. 9.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. L.H.Bailey.

- ^ Bailey 1906.

Bibliography

- Rodgers, Andrew Denny, III (1970). "Bailey, Liberty Hyde". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 395–397. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rodgers, A.D. 1949. Liberty Hyde Bailey: A Story of American Plant Sciences, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

- Bailey, L.H., ed. (1906) [1900]. Cyclopedia of American Horticulture. Volume 1 A-D, Volume 2 E–M, Volume 3 N–Q, Volume 4 R–Z (5th ed.).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - Bailey, L.H. (1919) [1900]. The standard cyclopedia of horticulture; a discussion, for the amateur, and the professional and commercial grower, of the kinds, characteristics and methods of cultivation of the species of plants grown in the regions of the United States and Canada for ornament, for fancy, for fruit and for vegetables; with keys to the natural families and genera, descriptions of the horticultural capabilities of the states and provinces and dependent islands, and sketches of eminent horticulturists (6 vols.) (3rd.[2nd. ed. 1916–1917 ed.). New York: Macmillan.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Banks, Harlan P. (1994). "Liberty Hyde Bailey 1858-1954. A biographical memoir" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Liberty Hyde Bailey Museum, South Haven, Michigan

- A Man for All Seasons: Liberty Hyde Bailey. Cornell University Library Online Exhibition

- Works by Liberty Hyde Bailey at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Liberty Hyde Bailey at the Internet Archive

- The Columbian Exposition, 1893

- Introduction to Bailey's volume of poetry, WIND AND WEATHER

- American botanists

- Pteridologists

- 1858 births

- 1954 deaths

- American botanical writers

- American garden writers

- American male writers

- American science writers

- Agrarian theorists

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Veitch Memorial Medal recipients

- Cornell University faculty

- Michigan State University alumni

- Michigan State University faculty

- People from Ithaca, New York

- People from Van Buren County, Michigan

- 19th-century botanists

- 20th-century botanists

- 19th-century American scientists

- 20th-century American scientists

- 19th-century American writers

- 20th-century American writers