Luby's shooting

| Luby's shooting | |

|---|---|

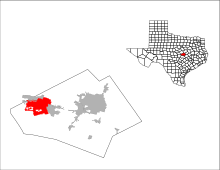

Location of Killeen, Texas | |

| Location | Killeen, Texas, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 31°05′37″N 97°43′26″W / 31.09361°N 97.72389°W |

| Date | October 16, 1991 12:39–12:51 p.m.[1] |

| Target | Customers and staff at a Luby's cafeteria, particularly women; first responders |

Attack type | Mass shooting, murder-suicide, shootout, femicide, vehicle ramming attack |

| Weapon | |

| Deaths | 24 (including the perpetrator) |

| Injured | 27 |

| Perpetrator | George Pierre Hennard |

| Motive | Unknown (widely believed to be misogyny, others have claimed misanthropy, isolation, and rejection) |

The Luby's shooting, also known as the Luby's massacre, was a mass shooting that took place on October 16, 1991, at a Luby's Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas. The perpetrator, George Hennard, drove his pickup truck through the front window of the restaurant before opening fire, killing 23 people and wounding 27 others. Hennard had a brief shootout with police in which he was seriously wounded but refused their orders to surrender and eventually killed himself.

The shooting was the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history, until it was surpassed in 2007 by the Virginia Tech shooting.[2][3]

Incident

[edit]On October 16, 1991, 35-year-old George Hennard, an unemployed former merchant seaman, drove a blue 1987 Ford Ranger pickup truck through the plate-glass front window of a Luby's Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas, at 12:39 p.m. October 16 was Boss's Day, and the cafeteria was unusually crowded with around 150 people.[4][5] Hennard then began firing from inside the truck while holding Glock 17 and Ruger P89 pistols;[6][7][8] the first victim was veterinarian Michael Griffith.[9] Hennard exited the truck and yelled, "All women of Killeen and Belton are vipers! This is what you've done to me and my family! This is what Bell County did to me ... this is payback day!"[10][11] He then opened fire on the patrons and staff with both pistols.[11] Hennard then circled around the cafeteria, selectively picking his victims. Hennard said "You bitch" to a woman before fatally shooting her.[11]

Hennard saw another woman hiding underneath a bench near the serving line and said, "Hiding from me, bitch?" before shooting her dead. Hennard then approached Steve Ernst, who was hiding underneath a table, before shooting him. Ernst then rolled over, holding his stomach.[11] The shooter then approached a woman with a crying baby. He barked at the woman, saying, "You with the baby. Get out before I change my mind." The woman ran out, holding the baby in her arms. After the woman left, Hennard shot Ernst's wife in the arm. The bullet passed through and killed 70-year-old Venice Ellen Henehan, Ernst's mother-in-law.[11]

During a brief lull in the shooting, Hennard approached the table of 28-year-old Tommy Vaughan in the rear of the cafeteria.[11] Huddled on the floor beside a window, Vaughan threw himself through the window, creating an escape route for others. Dozens of people pushed, shoved, and knocked each other down as they made their escape.[11] By the time police arrived a few minutes later, a third of the victims had managed to escape.[11][12][13]

Hennard reloaded at least three times before police arrived and engaged in a brief shootout. Wounded, he retreated to an area between the two bathrooms (people were hiding in these bathrooms and had blocked their doors). Police repeatedly ordered Hennard to surrender, but he refused, saying, "No, I'm going to kill more people."[14] Hennard was shot twice more by police, in the abdomen. Having depleted ammunition for one of his weapons and his injuries growing more severe, he fatally shot himself in the head with the final bullet.[8][5] He had shot and killed 23 people—10 of them with single shots to the head at point blank range—and wounded another 27.[8][15]

He discharged his weapons about 80 times during the shooting, and police discharged their weapons about 30 times.[16][17] Only the assailant was struck by police gunfire.[18]

Deaths

[edit]Victims of the shootings were:[1][19][7][11]

| Name | Age | Hometown |

|---|---|---|

| Patricia Carney | 57 | Belton |

| Jimmie Caruthers | 48 | Austin |

| Kriemhild Davis | 62 | Killeen |

| Steven Dody | 43 | Copperas Cove/Fort Cavazos |

| Alphonse "Al" Gratia | 71 | Copperas Cove |

| Ursula Gratia | 67 | Copperas Cove |

| Debra Gray | 33 | Copperas Cove |

| Michael Griffith | 48 | Copperas Cove |

| Venice Henehan | 70 | Metz, Missouri |

| Clodine Humphrey | 63 | Marlin |

| Sylvia King | 30 | Killeen |

| Zona Lynn | 65 | Marlin |

| Connie Peterson | 41 | Austin |

| Ruth Pujol | 55 | Copperas Cove |

| Su-Zann Rashott | 36 | Copperas Cove |

| John Romero Jr. | 29 | Copperas Cove |

| Thomas Simmons | 33 | Copperas Cove |

| Glen Arval Spivey | 55 | Harker Heights |

| Nancy Stansbury | 44 | Harker Heights |

| Olgica Taylor | 45 | Waco |

| James Welsh | 75 | Waco |

| Lula Welsh | 75 | Waco |

| Iva Juanita Williams | 64 | Temple |

Perpetrator

[edit]George Hennard | |

|---|---|

| Born | George Pierre Hennard October 15, 1956 Sayre, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | October 16, 1991 (aged 35) Killeen, Texas, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Education | Mayfield High School |

| Occupation | Unemployed |

George Pierre Hennard was born on October 15, 1956, in Sayre, Pennsylvania, into a wealthy family.[11] Hennard was the son of a Swiss-born surgeon and a homemaker.[20] He had two younger siblings, brother Alan and sister Desiree.[21] Since the age of 5, Hennard and his family moved across the country as his father worked at several army hospitals.[11] Hennard's family later moved to New Mexico, where his father worked at the White Sands Missile Range near Las Cruces. After graduating from Mayfield High School in 1974, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and served for three years, until he was honorably discharged.[22] Hennard later worked as a merchant mariner, but was dismissed for drug use.[6] Several months later, Hennard enrolled in a drug treatment program in Houston.[11]

Early in the investigation of the massacre, the Killeen police chief said that Hennard "had an evident problem with women for some reason".[6] After his parents divorced in 1983, his father moved to Houston, and his mother moved to Henderson, Nevada. The Glock 17 and Ruger P89 9mm pistols which Hennard used were purchased in February 1991 at Mike's Gun House, a gun shop in Henderson, Nevada.[10]

Hennard had begun to work at several different jobs, including construction crews in South Dakota and Killeen, while living part-time in Nevada with his mother. In Texas, he lived in a redbrick colonial home in Belton that his family had purchased in 1980 shortly after moving to Fort Hood.[11]

Hennard had stalked two women, sisters 23-year-old Jill Fritz and 19-year-old Jana Jemigan, who lived two blocks away from him in his neighborhood.[11] He sent them a five-page letter in June, part of which read: "Please give me the satisfaction of someday laughing in the face of all those mostly white treacherous female vipers from those two towns [Killeen and Belton] who tried to destroy me and my family" and "You think the three of us can get together some day?"[11][5] He also wrote that he was "truly flattered knowing I have two teenage groupie fans".[23]

Possible motive

[edit]Hennard was described as reclusive and belligerent, with an explosive temper. He was discharged from the Merchant Marine on May 11, 1989[7][10] for possession of marijuana and racial incidents. That same month, Hennard's seaman papers were suspended after he had a racial argument with another shipmate.[11] Numerous reports included accounts of Hennard's expressed hatred of women.[1][6][8] An ex-roommate of his said, "He hated blacks and Hispanics. He said women were snakes and always had derogatory remarks about them, especially after fights with his mother."[8] Survivors of the shootings later said Hennard had passed over men to shoot women. Fifteen of the 23 murder victims (65%) were women, as were many of the wounded. He called two of the victims a "bitch" before shooting them.[8]

In 1990, Hennard called Isaiah (Ike) R. Williams, a port agent for the national maritime union in Wilmington, California, stating that he needed a letter of recommendation to regain his papers and rejoin the Merchant Marine. "I don't recall having given him one," Williams claimed. Hennard had learned in mid-February that his attempt to be reinstated had been denied.[24] Several months later, he entered a drug-treatment program in Houston.[7][11]

Around two months before the shooting, Hennard entered a convenience store in Belton to buy breakfast. Mary Mead, the clerk of the store, claimed that Hennard had leaned over the counter and said, "I want you to tell everybody, if they don't quit messing around my house, something awful is going to happen."[7]

A week and a half before the shooting, Hennard collected his paycheck at a concrete company in Copperas Cove and announced he was quitting. Hennard also wondered aloud what would happen if he killed someone. "He got to talking about some of the people in Belton and certain women that had given him problems," coworker Bubba Hawkins claimed. "And he kept saying, 'Watch and see, watch and see'."[11]

On his 35th birthday, October 15, 1991, Hennard spoke with his mother on the phone. Later that evening, while eating a cheeseburger and french fries outside of Belton, Hennard had a sudden outburst of rage as he watched television coverage of Clarence Thomas's confirmation hearings. "When an interview with Anita Hill came on, he just went off," manager Bill Stringer said. "He started screaming, 'You bitch! You bastards opened the door for all the women!'"[11]

Aftermath

[edit]

An anticrime bill was scheduled for a vote in the U.S. House of Representatives the day after the massacre. Some of the Hennard victims had been constituents of Rep. Chet Edwards, and in response, he abandoned his opposition to a gun control provision that was part of the bill.[25][26] The provision, which did not pass, would have banned some weapons and magazines like one used by Hennard.[25]

Families of deceased victims, survivors, and policemen received counseling for grief, shock, and stress.[11]

The Texas State Rifle Association and others preferred that the state allow its citizens to carry concealed weapons.[25] Democratic Governor Ann Richards vetoed such bills, but in 1995, her Republican successor, George W. Bush, signed one into force.[27] The law had been campaigned for by Suzanna Hupp, who was present at the massacre; both of her parents, Alphonse "Al" Gratia and Ursula "Suzy" Gratia, were killed by Hennard.[28] She later testified that she would have liked to have had her .38 revolver,[10] but said, "It was a hundred feet away in my car." (She had feared that if she was caught carrying it she might lose her chiropractor's license.)[26] Hupp testified across the country in support of concealed handgun laws, and was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1996.[29]

A pink granite memorial stands behind the Killeen Community Center with the date of the event and the names of those killed.

Present site

[edit]The restaurant reopened five months after the massacre, but closed permanently on September 9, 2000.[30] In 2006, a buffet called "Yank Sing" occupied the former Luby's.[31] The restaurant remains open as of September 2024.

See also

[edit]- Gun violence in the United States

- Mass shootings in the United States

- 2009 Fort Hood shooting and 2014 Fort Hood shootings, two other mass shootings in Killeen, Texas

- San Ysidro McDonald's massacre, the deadliest mass shooting in the United States prior to the Luby's shooting[32] by James Huberty.

- List of shootings in Texas

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jankowski, Philip (October 16, 2011). "Survivors reflect on Oct. 16, 1991, Luby's shooting". Killeen Daily Herald. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Mass Murderers. True Crime. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books. 1993. ISBN 978-0783500041. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

huberty.

- ^ "Deadliest Mass Shootings in Modern US History Fast Facts". CNN. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Hart, Lianne; Wood, Tracy (October 17, 1991). "23 Shot Dead at Texas Cafeteria". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Hayes, Thomas C. (October 17, 1991). "Gunman Kills 22 and Himself in Texas Cafeteria". The New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy, J. Michael; Serrano, Richard A. (October 18, 1991). "Police May Never Learn What Motivated Gunman: Massacre: Hennard was seen as reclusive, belligerent. Officials are looking into possibility he hated women". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Terry, Don (1991-10-18). "Portrait of Texas Killer: Impatient and Troubled". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e f Chin, Paula (November 4, 1991). "A Texas Massacre". People. 36 (17). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Spellman, Jim (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood attack stirs painful memories for '91 massacre survivor". CNN. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "The Luby's Cafeteria Massacre of 1991 Crime Magazine". crimemagazine.com. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "A Texas Massacre". People. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Woodbury, Richard (October 28, 1991). "Crime: Ten Minutes in Hell". Time. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ Dawson, Carol (1 January 2010). House of Plenty: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Luby's Cafeterias. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-292-78234-1.

- ^ Blankenship, Kyle (October 15, 2016). "25 Years Later: Memories of Luby's shooting fade but don't die". Killeen Daily Herald. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Stone, Michael H.; Brucato, Gary (2019). The New Evil: Understanding the Emergence of Modern Violent Crime. Amherst, New York: Prometheus. pp. 44–45.

- ^ writer, Lauren Dodd | Herald staff (2021-10-17). "30 years later: Mass shooting trend lasts long after Luby's massacre". The Killeen Daily Herald. Retrieved 2024-10-13.

- ^ "Books closed on Luby's cafeteria massacre - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved 2024-10-13.

- ^ Clark, John (2001-10-16). "Gunpowder smell filled". Temple Daily Telegram. Retrieved 2024-10-13.

- ^ "Victims of the Texas Cafeteria Massacre With AM-Cafeteria Massacre". Associated Press. October 19, 1991. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Dawson, Carol (1 January 2010). House of Plenty: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Luby's Cafeterias. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-292-78234-1.

- ^ "A Texas Massacre – Vol. 36 No. 17". people.com. 1991-11-04. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ "Texas massacre had eerie link to movie 'The Fisher King'". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ Kennedy, J. Michael; Serrano, Richard A. (October 18, 1991). "Police May Never Learn What Motivated Gunman: Massacre: Hennard was seen as reclusive, belligerent. Officials are looking into possibility he hated women". Los Angeles Times. p. 2.

- ^ Terry, Don (October 18, 1991). "Portrait of Texas Killer: Impatient and Troubled". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Douglas, Carlyle C. (October 20, 1991). "Dead: 23 Texans and 1 Anti-Gun Measure". The New York Times. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Kopel, David B. (2012). "Killeen, Texas, Massacre". In Carter, Gregg Lee (ed.). Guns in American Society. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 648–650. ISBN 978-0-313-38671-8.

- ^ Duggan, Paul (March 16, 2000). "Gun-Friendly Governor". Washington Post. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Ruddy, Jim (1992). "The Luby's Massacre – Interview with Suzanna Gratia Hupp (1992)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- ^ "National Advisory Committee on Violence Against Women, Biographical Information" (PDF). justice.gov. June 19, 2006. p. 5. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- ^ "Luby's in Killeen, Texas, site of 1991 massacre, closes its doors". CNN. Associated Press. September 11, 2000. Archived from the original on April 23, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ Nathan, Robert (October 15, 2006). "Luby's tragedy: 15 years later". Killeen Daily Herald.

- ^ Kennedy, J. Michael; Serrano, Richard A. (October 18, 1991). "Police May Never Learn What Motivated Gunman: Massacre: Hennard was seen as reclusive, belligerent. Officials are looking into possibility he hated women". Los Angeles Times. p. 3.

Further reading

[edit]- "Shooting rampage at Killeen Luby's left 24 dead". Houston Chronicle. August 11, 2001. Archived from the original on December 1, 2011.

- Winingham, Ralph (1997). "Texas massacre, fear of crime spur concealed-gun laws". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on January 28, 1999.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Luby's shooting at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Luby's shooting at Wikiquote

- 1990s crimes in Texas

- 1990s vehicular rampage

- 1991 in Texas

- 1991 mass shootings in the United States

- 1991 murders in the United States

- 1991 road incidents

- Attacks on buildings and structures in 1991

- Attacks on buildings and structures in Texas

- Attacks on restaurants in the United States

- Bell County, Texas

- Deaths by firearm in Texas

- Killeen–Temple–Fort Hood metropolitan area

- Mass murder in Texas

- Mass murder in the United States in the 1990s

- Mass shootings in Texas

- Mass shootings in the United States

- Mass shootings involving Glock pistols

- Massacres in 1991

- Massacres in the United States

- Massacres of women

- Misogynist terrorism

- Murder–suicides in Texas

- Presidency of George H. W. Bush

- October 1991 crimes in the United States

- Vehicular rampage in the United States

- Violence against women in Texas