Luck

Luck is the phenomenon and belief that defines the experience of improbable events, especially improbably positive or negative ones. The naturalistic interpretation is that positive and negative events may happen at any time, both due to random and non-random natural and artificial processes, and that even improbable events can happen by random chance. In this view, the epithet "lucky" or "unlucky" is a descriptive label that refers to an event's positivity, negativity, or improbability.

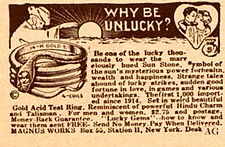

Supernatural interpretations of luck consider it to be an attribute of a person or object, or the result of a favorable or unfavorable view of a deity upon a person. These interpretations often prescribe how luckiness or unluckiness can be obtained, such as by carrying a lucky charm or offering sacrifices or prayers to a deity. Saying someone is "born lucky" may hold different meanings, depending on the interpretation: it could simply mean that they have been born into a good family or circumstance; or that they habitually experience improbably positive events, due to some inherent property, or due to the lifelong favor of a god or goddess in a monotheistic or polytheistic religion.

Many superstitions are related to luck, though these are often specific to a given culture or set of related cultures, and sometimes contradictory. For example, lucky symbols include the number 7 in Christian-influenced cultures and the number 8 in Chinese-influenced cultures. Unlucky symbols and events include entering and leaving a house by different doors or breaking a mirror[1] in Greek culture, throwing rocks into a whirlwind in Navajo culture,[2] and ravens in Western culture. Some of these associations may derive from related facts or desires. For example, in Western culture opening an umbrella indoors might be considered unlucky partly because it could poke someone in the eye, whereas shaking hands with a chimney sweep might be considered lucky partly because it is a kind but unpleasant thing to do given the dirty nature of their work. In Chinese and Japanese culture, the association of the number 4 as a homophone with the word for death may explain why it is considered unlucky. Extremely complicated and sometimes contradictory systems for prescribing auspicious and inauspicious times and arrangements of things have been devised, for example feng shui in Chinese culture and systems of astrology in various cultures around the world.

Many polytheistic religions have specific gods or goddesses that are associated with luck, both good and bad, including Fortuna and Felicitas in the Ancient Roman religion (the former related to the words "fortunate" and "unfortunate" in English), Dedun in Nubian religion, the Seven Lucky Gods in Japanese mythology, mythical American serviceman John Frum in Polynesian cargo cults, and the inauspicious Alakshmi in Hinduism.

Etymology and definition

[edit]

The English noun luck appears comparatively late, during the 1480s, as a loan from Low German, Dutch or Frisian luk, a short form of gelucke (Middle High German gelücke). Compare to old Slavic word lukyj (лукый) - appointed by destiny and old Russian luchaj (лучаи) - destiny, fortune. It likely entered English as a gambling term, and the context of gambling remains detectable in the word's connotations; luck is a way of understanding a personal chance event. Luck has three aspects:[3][4][5]

Before the adoption of luck at the end of the Middle Ages, Old English and Middle English expressed the notion of "good fortune" with the word speed (Middle English spede, Old English spēd); speed besides "good fortune" had the wider meaning of "prosperity, profit, abundance"; it is not associated with the notion of probability or chance but rather with that of fate or divine help; a bestower of success can also be called speed, as in "Christ be our speed" (William Robertson, Phraseologia generalis, 1693).

The notion of probability was expressed by the Latin loanword chance, adopted in Middle English from the late 13th century, literally describing an outcome as a "falling" (as it were of dice), via Old French cheance from Late Latin cadentia "falling". Fortuna, the Roman goddess of fate or luck, was popular as an allegory in medieval times, and even though it was not strictly reconcilable with Christian theology, it became popular in learned circles of the High Middle Ages to portray her as a servant of God in distributing success or failure in a characteristically "fickle" or unpredictable way, thus introducing the notion of chance.[citation needed]

Interpretations

[edit]Luck is interpreted and understood in many different ways.

Lack of control

[edit]Luck refers to that which happens to a person beyond that person's control. This view incorporates phenomena that are chance happenings, a person's place of birth for example, but where there is no uncertainty involved, or where the uncertainty is irrelevant. Within this framework, one can differentiate between three different types of luck:

- Constitutional luck, that is, luck with factors that cannot be changed. Place of birth and genetic constitution are typical examples.

- Circumstantial luck—with factors that are haphazardly brought on. Accidents and epidemics are typical examples.

- Ignorance luck, that is, luck with factors one does not know about. Examples can be identified only in hindsight.

Circumstantial luck with accidental happenstance of favorable discoveries and/or inventions is serendipity.

Fallacy

[edit]Another view holds that "luck is probability taken personally." A rationalist approach to luck includes the application of the rules of probability and an avoidance of unscientific beliefs. The rationalist thinks that the belief in luck is a result of poor reasoning or wishful thinking. To a rationalist, a believer in luck who asserts that something has influenced his or her luck commits the "post hoc ergo propter hoc" logical fallacy: that because two events are connected sequentially, they are connected causally as well. In general, this fallacy is that:

- A luck-attracting event or action happens;

- Then a positive outcome happens;

- Therefore, the event or action influenced the outcome.

More contemporary authors writing on the subject believe that the definition of good destiny is: One who enjoys good health; has the physical and mental capabilities of achieving his goals in life; has good appearance, and; has happiness in mind and is not prone to accidents.[8]

In the rationalist perspective, probability is only affected by confirmed causal connections.

The gambler's fallacy and inverse gambler's fallacy both explain some reasoning problems in common beliefs in luck. They involve denying the unpredictability of random events: "I haven't rolled a seven all week, so I'll definitely roll one tonight".

Philosopher Daniel Dennett wrote that "luck is mere luck" rather than a property of a person or thing.[9]

Essence

[edit]

There is also a series of spiritual, or supernatural beliefs regarding fortune. These beliefs vary widely from one to another, but most agree that luck can be influenced through spiritual means by performing certain rituals or by avoiding certain circumstances.

Luck can also be a belief in an organization of fortunate and unfortunate events. Luck is a form of superstition which is interpreted differently by different individuals. Carl Jung coined the term synchronicity, which he described as "a meaningful coincidence".

Abrahamic religions believe God controls future events; belief in luck or fate is criticised in Isaiah 65:11–12:

But you who forsake the Lord,

who forget my holy mountain,

who set a table for Fortune

and fill cups of mixed wine for Destiny,

I will destine you to the sword,

and all of you shall bow down to the slaughter

Belief in the extent of Divine Providence varies; most acknowledge providence as at least a partial, if not complete influence on luck. Christianity, in its early development, accommodated many traditional practices which at different times, accepted omens and practiced forms of ritual sacrifice in order to divine the will of their supreme being or to influence divine favoritism. The concepts of "Divine Grace" or "Blessing" as they are described by believers closely resemble what is referred to as "luck" by others.

Mesoamerican religions, such as the Aztecs, Mayans and Incas, had particularly strong beliefs regarding the relationship between rituals and the gods, which could in a similar sense to Abrahamic religions be called luck or providence. In these cultures, human sacrifice (both of willing volunteers and captured enemies), as well as self-sacrifice by means of bloodletting, could possibly be seen as a way to propitiate the gods and earn favor for the city offering the sacrifice. An alternative interpretation[10] would be that the sacrificial blood was considered as a necessary element for the gods to maintain the proper working order of the universe, in the same way that oil would be applied to an automobile to keep it working as designed.

Many traditional African practices, such as voodoo and hoodoo, have a strong belief in superstition. Some of these religions include a belief that third parties can influence an individual's luck. Shamans and witches are both respected and feared, based on their ability to cause good or bad fortune for those in villages near them.

Self-fulfilling prophecy

[edit]Some evidence supports the idea that belief in luck acts like a placebo, producing positive thinking and improving people's responses to events.

In personality psychology, people reliably differ from each other depending on four key aspects: beliefs in luck, rejection of luck, being lucky, and being unlucky.[11] People who believe in good luck are more optimistic, more satisfied with their lives, and have better moods.[11] People who believe they are personally unlucky experience more anxiety, and less likely to take advantage of unexpected opportunities.[12] One 2010 study found that golfers who were told they were using a "lucky ball" performed better than those who were not.[12]

Some people intentionally put themselves in situations that increase the chances of a serendipitous encounter, such as socializing with people who work in different fields.[12]

Social aspects

[edit]

Games

[edit]The philosopher Nicholas Rescher has proposed that the luck of someone's result in a situation of uncertainty is measured by the difference between this party's yield and expectation: λ = Y - E. Thus skill enhances expectation and reduces luck. The extent to which different games will depend on luck, rather than skill or effort, varies considerably. For example, chess does not involve any random factors (beyond the determination of which player moves first), while the outcome of Snakes and Ladders is entirely based on random dice rolls. In poker, especially games with a communal board, pure luck may decide a winning hand. Luck in games involving chance is defined as the change in a player's equity after a random event such as a die roll or card draw.[13] Luck is positive (good luck) if the player's position is improved and negative (bad luck) if it is worsened. A poker player who is doing well (playing successfully, winning) is said to be "running good".[14]

Almost all sports contain elements of luck. A statistical analysis in the book The Success Equation attempted to elucidate the differing balance between skill and luck with respect to how teams finished in the major North American sports leagues. This analysis concluded that, on a luck-skill continuum, the NBA had the most skill-dependant result while that of the NHL was most luck-dependant.[15]

Lotteries

[edit]A defining feature of a lottery is that winners are selected purely by chance. Marketing and other discussions regarding lotteries often mention luck but tend to underplay the actual prospects of winning, which are usually millions to one against.[16]

Means of resolving issues

[edit]"Leaving it to chance" is sometimes a way of resolving issues for example, where there are two possible outcomes, flipping a coin may determine the outcome. This practice has gone on for thousands of years, a common contemporary example is the coin toss at the start of a sporting event which may determine who goes first.[17]

Numerology

[edit]Most cultures consider some numbers to be lucky or unlucky. This is found to be particularly strong in Asian cultures, where the obtaining of "lucky" telephone numbers, automobile license plate numbers, and household addresses (such as those which contain the digit 6 or 8) are actively sought, sometimes at great monetary expense.

Numerology, as it relates to luck, is closer to an art than to a science, yet numerologists, astrologists or psychics may disagree. It is interrelated to astrology, and to some degree to parapsychology and spirituality and is based on converting virtually anything material into a pure number, using that number in an attempt to detect something meaningful about reality, and trying to predict or calculate the future based on lucky numbers. Numerology is folkloric by nature and started when humans first learned to count. Through human history it was, and still is, practiced by many cultures of the world from traditional fortune-telling to on-line psychic reading. Dudley describes numerology as, "the delusion that numbers have power over events."[18]

Science

[edit]Different thinkers like Thomas Kuhn have discussed the role of chance in scientific discoveries. Richard Wiseman did a ten-year scientific study into the nature of luck that has revealed that, to a large extent, people make their own good and bad fortune. His research revealed that "Lucky people generate their own good fortune via four basic principles. They are skilled at creating and noticing chance opportunities, making lucky decisions by listening to their intuition, creating self-fulfilling prophecies via positive expectations, and adopting a resilient attitude that transforms bad luck into good."[19] Researchers have suggested that good luck and good mood often co-occur (Duong & Ohtsuka, 2000)[20] and that people who believe themselves to be lucky are often comparatively happy and optimistic whereas people who believe themselves to be unlucky may feel comparatively anxious and depressed (Day & Maltby, 2003; Wiseman, 2003).[19][21] Luck can also correlate with superstitious behaviors that increase opportunities of good fortune occurring like avoiding walking under ladders or blowing left and right for safe travels before crossing train tracks, which inadvertently increases your chances of seeing an oncoming train.[22][23]

Although previous studies have explored the antecedents and consequences of luck using attribution theory (e. g., Fischoff, 1976; Weiner et al., 1987),[24][25] personality variables (Darke & Freedman, 1997a;b),[26] and more recently a cognitive priming approach (DeMarree et al., 2005; Kramer & Block, 2008) research on the underlying mechanism of how luck influences consumer judgment and behavior has been noticeably absent in the extant literature. Moreover, in much of this previous work, luck is manipulated in a way that is very likely to elicit positive affect as well. Thus, it is difficult to articulate whether the observed effects of luck are due to chronic beliefs about luck, temporary changes in how lucky people feel, or because of changes caused by the positive affect that is experienced. Their research showed that priming participants subliminally with luck-related stimuli made them feel luckier and happier. It was also found that the effects of priming luck using subliminal messages increased participants' estimates of the likelihood of favorable events, their participation in lotteries, the amount of money they invested in relatively risky financial options and these effects appeared to be mediated by temporary changes in perceptions of luck rather than by affect.[27][28]

In religion and mythology

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, taught his followers not to believe in luck. He taught that all things which happen must have a cause, either material or spiritual, and do not occur due to luck, chance or fate. The idea of moral causality, karma (Pali: kamma), is central in Buddhism. In the Sutta Nipata, the Buddha is recorded as having said the following about selling luck:

Whereas some religious men, while living of food provided by the faithful make their living by such low arts, such wrong means of livelihood as palmistry, divining by signs, interpreting dreams ... bringing good or bad luck ... invoking the goodness of luck ... picking the lucky site for a building, the monk Gautama refrains from such low arts, such wrong means of livelihood. D.I, 9–12[29]

Belief in luck is prevalent in many predominantly Buddhist countries. In Thailand, Buddhists may wear verses (takrut) or lucky amulets which have been blessed by monks for protection against harm.[30]

Christianity and Judaism

[edit]The book of Proverbs 16:33 states that "the lot is cast into the lap, but its every decision is from the Lord". Ecclesiastes 9:11 states (in a passage that describes events with different outcomes - e.g. a race, a battle, the gaining of wealth and favour) that "time and chance happeneth to them all". Whilst the latter passage from Ecclesiastes suggests no things in human affairs are certain, the extract from Proverbs indicates that the outcome of something as apparently random as the rolling of dice or the tossing of a coin remains subject to God's will or sovereignty. In his book God, Chance and Purpose: Can God have it both ways?,[31] Bartholomew argues that chance is part of God's creation but that not even God can accurately predict what chance will do.[32]

God's sovereignty involves two aspects. God's active will or sovereignty would involve something God causes to happen such as the leading of wicked King Ahab into battle (2 Chronicles 18:18-19). Ahab's death was not merely the result of a randomly shot arrow, but as 2 Chronicles 18 reveals, God actively directed the events that led Ahab into battle and used that randomly shot arrow to accomplish his intended will for Ahab that day.[33]

God's passive will involves God allowing, rather than causing, something to happen. Chapter 1 of the book of Job illustrates this in what God allowed Satan to do in the life of Job.[34] It is also involved in the evil that God allowed Joseph's brothers to do to Joseph in order to accomplish a greater good, a good not apparent to Joseph until years later (Genesis 50:20).[35]

Hinduism

[edit]In Hinduism the Bhagavad-Gita values "Purushartha" more than mere Luck or Fate.

The Gita says; "Set thy heart upon selfless performance of thy natural duty (Svakarma, Svadharma), but never on its reward. Work not for a reward; but never cease to do thy work" (Gita, 2.47).[36]

There are five causes of all actions as given in the Samkhya wisdom; says Gita—

"The physical body (adhisthana), the lower 'I am' (karta), the means of perception (karanam), the varied multiple efforts (vividhasch pruthak cheshta) and the Cosmic Wheel of Action (daivam), these five sources together are responsible for success or failure of any action" ( Gita, 18 . 14–15 ).[37]

Here the word "daivam" does not mean luck, fate, fortune, providence, or destiny. None of these English words are the exact synonym for the Sanskrit word "Daivam" here. "Daivam" is the Cosmic Wheel of Action (Kshara-gati, Apara-Prakriti, Maya) that keeps the perfect account of our past and present actions.

A man who says "Nothing is impossible for me; I am the only hero of all these achievements; who else is there like me?" He is a man of clouded vision and he does not see the Truth.

Islam

[edit]The definition which is much closer to the concept of luck in Islam is "a force that brings good fortune or adversity" Quran 17:13: "And (for) every man We have fastened to him his fate (fortune) in his neck, and We will bring forth for him (on the) Day (of) the Resurrection a record which he will find wide open". A very long discussion continues on how this prefixed destiny, fortune or luck defines attitudes and living behavior and so as to how much amends one can make in this predetermined fate by one's own contribution through positive actions in accordance with the teachings of Islam. There is no concept of luck in Islam other than actions determined by Allah based on the merit of the choice made by human beings. It is stated in the Qur'an (Sura: Adh-Dhariyat (The Winds that Scatter) verse:22) that one's sustenance is pre-determined in heaven when the Lord says: "And in the heaven is your provision and that which ye are promised." One should supplicate to Allah to better one's life rather than hold faith in un-Islamic acts such as using "lucky charms". In the Arabic language there is a word which directly means "luck", which is حظ ḥaẓẓ, and a related word for "lucky", محظوظ maḥẓūẓ. It is also forbidden to believe in luck or anything else related to luck, as it is classified as shirk (associating partners to Allah or giving any share of any attribution which belongs to Allah and Allah alone).[citation needed]

The Tunisians retain some native beliefs of Berber origin such as the evil eye.[38] A number of practices, such as shutters painted blue are also used to repel evil spirits.[39]

Belief measurement

[edit]

Darke and Freedman (1997)[40] were the first researchers systematically to address directly both the concept and the measurement of belief in luck as a deterministic and personal attribute. They define luck belief as the perception that good luck is "a somewhat stable characteristic that consistently favors some people but not others".[40] They define disbelief in luck as "a tendency to agree with the rational view of luck as random and unreliable" (p. 490). To capture their unidimensional definition of irrational luck belief, Darke and Freedman developed a 12-item measure.[40] Unfortunately, they found their measure "does not seem particularly good at distinguishing between people who [say] they [are] typically lucky from those who [say] they [are] typically unlucky".[40] They also found factor analyses of their measure produced a multi-component solution,[40] as did Prendergast and Thompson (2008).[41]

André (2006)[42] proposed a model of luck-related perceptions that includes separate positive and negative beliefs. She found the positive and negative components of personal luck beliefs correlate highly, suggesting they are conceptually very close or in fact the same. Maltby et al. (2008)[43] proposed a six-dimensional model of beliefs around luck, but empirical analyses supported only a four-dimensional model: belief in being personally lucky; belief in being personally unlucky; general belief in luck; and rejection of belief in luck.[citation needed]

Thompson and Prendergast (2013)[44] clarified the concepts of belief in luck and belief in personal luckiness. They addressed the logical problem that nobody who disbelieves in luck could consider themselves lucky by differentiating between belief in luck as a deterministic phenomenon that affects the future, on one hand, and on the other, belief in personal luckiness as an appraisal of how fortunately or otherwise chance events in the past might have turned out. They developed and validated an internationally applicable scale to measure, respectively, belief in luck and personal luckiness constructs. They found no correlation between the constructs and no evidence of a distinction between positive and negative aspects of each, suggesting they represent two discrete and unidimensional constructs. Belief in luck and personal luckiness were also found to correlate differently with personality and psychological variables, such as the Big Five and affect.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Gunther, Max. "The Luck Factor" Harriman House Ltd 1977. ISBN 9781906659950

- Hartman, Robert (ed.), Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy and Psychology (London: Routledge, 2019).

- Mlodinow, Leonard. "The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives" Penguin Group, 2008. ISBN 0375424040

- Mauboussin, Michael. "The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing." Harvard Business Review Press, 2012 ISBN 9781422184233

- Rosenthal, Jeff, Knock on Wood: Luck, Chance, and the Meaning of Everything, HarperCollins, 2018 ISBN 1443453072

- Rescher, Nicholas. "Luck", Farrar Straus Giroux 1995. Reissued University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001

- Sauder, M. (2020). A Sociology of Luck. Sociological Theory.

- Taleb, Nassim N. "Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets" Random House 2001 ISBN 0812975219

References

[edit]- ^ "Breaking a mirror - Meaning of broken mirror". www.mirrorhistory.com. Retrieved 2022-09-05.

- ^ "Navajo Superstitions". navajocodetalkers.org. Retrieved 2024-08-23.

- ^ Rescher, N., Luck: the brilliant randomness of everyday life p. 32. "Luck accordingly involves three things: (1) a beneficiary or maleficiary, (2) a development that is benign (positive) or malign (negative) from the stand point of the interests of the affected individual, and that, moreover, (3) is fortuitous (unexpected, chancy, unforeseeable.)"

- ^ CHANCE News 4.15 Archived 2017-06-18 at the Wayback Machine ...the definition in the Oxford English dictionary: "the fortuitous happening of an event favorable or unfavorable to the interest of a person"

- ^ Rescher, N., Luck: the brilliant randomness of everyday life p. 28. "Luck is a matter of having something good or bad happen that lies outside the horizon of effective foreseeability."

- ^ Rescher, N., Luck: the brilliant randomness of everyday life p. 32. "Luck thus always incorporates a normative element of good or bad: someone must be affected positively or negatively by an event before its realization can properly be called lucky."

- ^ Rescher, N., Luck: the brilliant randomness of everyday life p. 32. ..."that as a far as the affected person is concerned, the outcome came about "by accident." "

- ^ Sumit Kumar Sirkar, Pothi (2010). "How to be Lucky and Successful in Life". Pothi.com. p. 5. Retrieved 2012-10-04.

- ^ Elbow Room by Daniel Clement Dennett, p. 92. "We know it would be superstitious to believe that "there actually is such a thing as luck" - something a rabbits' foot might bring - but we nevertheless think there is an unsuperstitious and unmisleading way of characterising events and properties as merely lucky."

- ^ Burland, C. A (1985). The Aztecs: gods and fate in ancient Mexico. London: Orbis Publishing.

- ^ a b Maltby, J., Day, L., Gill, P., Colley, A., Wood, A.M. (2008). Beliefs around luck: Confirming the empirical conceptualization of beliefs around luck and the development of the Darke and Freedman beliefs around luck scale Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 655–660.

- ^ a b c "The Science Of Luck". Archived from the original on 2022-07-18. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ Zare, Douglas. "A Measure of Luck". Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Miller, Ed (Nov 27, 2009). "The Pitfalls of Running Good". CardPlayer.com. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

I've always thought that one of the worst things that can happen to new poker players is for them to run really good right out of the gate. If they rack up a number of big wins early on, a couple of bad things can happen.

- ^ Vox (2017-06-05), Why underdogs do better in hockey than basketball, archived from the original on 2021-10-29, retrieved 2018-07-02

- ^ Stearns, James M.; Borna, Shaheen (1995-01-01). "The ethics of lottery advertising: Issues and evidence". Journal of Business Ethics. 14 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1007/BF00873735. ISSN 1573-0697. S2CID 154717674.

- ^ "The History of the Coin Toss | The Royal Mint". www.royalmint.com. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ Dudley, Underwood (1997). Numerology or What Pythagoras Wrought. Spectrum. Vol. 19. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. doi:10.1090/spec/019. ISBN 978-1-4704-5283-4. S2CID 243070708.

- ^ a b Wiseman, R. (2003). The luck factor. London, UK: Random House.

- ^ Duong, T.,&Ohtsuka, K. (2000). TheVietnamese-language SouthOaksGambling Screen for the Australian context. In J. McMillen, & L. Laker (Eds.), Developing strategic alliances: Proceedings of the 9th National Association for Gambling Studies Conference, Gold Coast, Queensland 1999 (pp. 161−171). Kew, Australia: The National Association for Gambling Studies.

- ^ Wiseman, R., & Watt, C. (2004). Measuring superstitious belief: Why lucky charms matter. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1533−1541.

- ^ "A rail safety superstition • TrackSafe". www.tracksafe.co.nz. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ^ Shortland, Edward (2011). Traditions and superstitions of the New Zealanders : with illustrations of their manners and customs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-10908-6. OCLC 820719167.

- ^ Fischoff, B. (1976). Attribution theory and judgment under uncertainty. In J. H. Harvey, W. J. Ickes, & R. F. Kidd (Eds.), New directions in attribution research (Vol. 1, 421−452). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ^ Weiner, B., Frieze, I., Kukla, A., Reed, L., Rest, S., & Rosenbaum, R. M.(1987). Perceiving the causes of success and failure. In Edward E. Jones, David E. Kanouse, Harold H. Kelley, Richard E. Nisbett, Stuart Valins, & Bernard Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behaviors pp. 95−120. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- ^ Darke, P. R., & Freedman, J. L. (1997a). The belief in good luck scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 2, 486−511.

- ^ DeMarree, K. G., Wheeler, S. C., & Petty, R. E. (2005). Priming a new identity: Self-monitoringmoderates the effects of nonself primes on self-judgments and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(5), 657−671.

- ^ Kramer, T., & Block, L. (2008). Conscious and non-conscious components of superstitious beliefs in judgment and decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(6), 783−793.

- ^ "A Basic Buddhism Guide: Good Luck and Fate". Buddhanet.net. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ^ Thai Amulets (2007-02-09). "Thai Amulets". Thailand Life. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ^ Bartholomew, David J. (2008). God, chance, and purpose : can God have it both ways?. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-38723-4. OCLC 249076888.

- ^ Dembski, William (2003), "The Chance of the Gaps", GOD AND DESIGN, Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis, pp. 251–274, doi:10.4324/9780203398265_chapter_14, ISBN 978-0-203-40002-9, retrieved 2021-09-05

- ^ Hamilton, Mark W. (2019). "Riddles and Revelations: Explorations into the Relationship between Wisdom and Prophecy in the Hebrew Bible ed. by Mark J. Boda, Russell L. Meek, and William R. Osborne". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 81 (4): 753–755. doi:10.1353/cbq.2019.0191. ISSN 2163-2529. S2CID 204517104.

- ^ Giberson, Karl W. (2015). "Chance, Divine Action and the Natural Order of Things". Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 27 (1): 100–109. doi:10.5840/jis2015271/27. ISSN 0890-0132.

- ^ Katzoff, Charlotte (1998). "Divine Causality and Moral Responsibility in the Story of Joseph and His Brothers". Iyyun: The Jerusalem Philosophical Quarterly / עיון: רבעון פילוסופי. 47: 21–40. ISSN 0021-3306. JSTOR 23352599.

- ^ Mukundananda, Swami. "Chapter 2, Verse 47 – Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God – Swami Mukundananda". www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ Mukundananda, Swami. "Chapter 18, Verse 15-16 – Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God – Swami Mukundananda". www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "La Tunisie de A à Z, Khomsa". Saisons tunisiennes. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

- ^ Pagès, Jean-Louis (2005). Tunisie-Plus (in French). Limoges: éd. Solilang. p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e Darke P.R. & Freedman J.L. (1997). The belief in good luck scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 486–511.

- ^ Prendergast, G.P. & Thompson, E.R.(2008). Sales promotion strategies and belief in luck. Psychology & Marketing, 25 (11), 1043–1062.

- ^ Andre, N. (2006). Good fortune, luck, opportunity and their lack: How do agents perceive them? Personality and Individual Differences,40 (7), 1461–1472.

- ^ Maltby, J., Day, L., Gill, P., Colley, A., & Wood, A. M. (2008). Beliefs around luck: Confirming the empirical conceptualization of beliefs around luck and the development of the Darke and Freedman Beliefs Around Luck scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 655–660.

- ^ Thompson, E. R., & Prendergast, G. P. (2013). Belief in Luck and Luckiness: Conceptual Clarification and Measure Validation. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(4), 501-506.