Newington Green Unitarian Church

| Newington Green Unitarian Church | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| 51°33′08″N 0°05′06″W / 51.55217°N 0.08492°W | |

| Location | 39A Newington Green, London N16 9PR |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches (British Unitarians) |

| Website | www.new-unity.org |

| History | |

| Founded | 1708 |

| Clergy | |

| Minister(s) | Andrew Pakula |

Newington Green Unitarian Church (NGUC) in north London is one of England's oldest Unitarian churches. It has had strong ties to political radicalism for over 300 years, and is London's oldest Nonconformist place of worship still in use. It was founded in 1708 by English Dissenters, a community of which had been gathering around Newington Green for at least half a century before that date. The church belongs to the umbrella organisation known as the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, and has had an upturn in its fortunes since the turn of the millennium.

Its most famous minister was Dr Richard Price, a political radical who is remembered for his role in the Revolution Controversy, a British debate about the French Revolution, but who also did pioneering work in finance and statistics. The most famous member of its congregation was Mary Wollstonecraft, who drew inspiration from Price's sermons in her work, both in arguing for the new French republic and in raising the issue of the rights of women. Wollstonecraft is commemorated by a mural in the church which has been described as "the birthplace of feminism".[1]

The building, which faces the north side of the green, was extended in 1860, and was listed in 1953. It lies within the London Borough of Hackney, although the rest of the green is part of the London Borough of Islington.

Background to its creation

After the end of Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth and the Restoration of Charles II, those in England and Wales who were not members of the Church of England found themselves in an uncomfortable position. Several pieces of legislation, known collectively as the Clarendon Code, made their lives difficult. The first restricted public office to Anglicans. The Act of Uniformity the following year was a step too far for many clergymen, and about 2,000 of them left the established church in the Great Ejection of 1662. The third act forbad unauthorised religious meetings of more than five people. The final one prohibited Nonconformist clergymen from living within five miles of a parish from which they had been banned. Where the ministers went, their flocks tended to follow.[2] Some of these restrictions were ameliorated a generation later, with the passing of the Act of Toleration 1689, which guaranteed freedom of worship for certain groups. It allowed Nonconformists (or Dissenters) their own places of worship and their own teachers and preachers, subject to certain oaths of allegiance and to the registering of these locations and leaders, but it perpetuated their existing social and political disabilities, including their exclusion from political office and also from universities (Oxford and Cambridge were the only universities in England and Wales at that time).

Roman Catholics were specifically targeted by these acts, and many of them went underground. Some Christians who had hoped for a more Protestant Reformation within the Established Church chose to emigrate, especially to the American colonies, as the Pilgrim Fathers had done in 1620. Others maintained their faith openly, and lived with the restrictions the state placed upon them, moving to areas where they were tolerated. Often they set up educational establishments, known in general as dissenting academies, which were intellectually and morally more rigorous than the universities.[3] One such was at Newington Green, then an agricultural village a few miles from London, but now within Inner London. Unitarianism or Rational Dissent – "that intellectual aristocracy in the ranks of Dissent, as historians often characterise it" – had an obvious affinity with education, critical enquiry, and challenges to the status quo, and is "one of the roots of modern English Culture".[4] A critical mass of such people, including "dissident intellectuals, pedagogues with reforming ideas and Dissenters"[5][6] and "the well-to-do edge of radical Protestantism"[7] clustered around Newington Green. Not all of these free-thinkers were Unitarians, such as Quaker John Coakley Lettsome (physician, philanthropist, and abolitionist) or the Anglicans Vicesimus Knox (pacifist and writer) and George Gaskin (minister and long-time secretary of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge), but most had some connections to the chapel on the green.

The building and its religious neighbours

The original building of 1708 was financed with £300, equivalent to £60,883 in 2023,[8] from Edward Harrison, a goldsmith.[9] He leased it to the trustees of the congregation, who furnished it with pulpit, pews, and so on, raising the necessary £96 from about 20 subscribers, primarily by hiring or selling pews.[10] It was a "substantial brick building, of nearly square form, with the high, tiled, projecting roof, common at its era",[11] "Historic views show that the original façade had a small pediment against a large hipped roof, with a central oval window below."[12] It was too plain for Wollstonecraft's Anglican tastes,[13] and one of her biographers thought it defiantly stark.[14] This building was substantially extended and improved in the mid-19th century. An internal gallery was built to increase the seating available, and a few years later the roof and apse were renewed, and a "stuccoed frontage" was built, "mirroring the original façade with a three-bay front with two round-headed windows, but with added Tuscan pilasters and a large pediment".[15]

Other religious institutions existed nearby. St Matthias, one of London's foremost High Churches, was built a couple of hundred yards away between 1849 and 1853, partly with money from a rich doctor named Robert Brett,[16] who thought that the Dissenting chapels were attracting so many worshippers in part because the Anglican pews were full.[17] Jews fleeing the pogroms of the Russian Empire established a congregation in the area by 1876, and built the Dalston Synagogue in adjoining Poets Road in 1885. This Victorian Gothic building became one of the leading synagogues of London, with Jacob Koussevitzsky as its cantor from 1936.[18] Fronting onto the green itself was the China Inland Mission headquarters (circa 1895), an organisation responsible for 18,000 converts to Christianity that had been founded by James Hudson Taylor at the height of the Victorian era.[19] St Matthias still operates as a church; the synagogue was demolished in the 1970s; the missionary building is now international student housing.

Newington Green fell within the old parish boundaries of Stoke Newington. Although the latter village, centred on Church Street, was a mile away from the hamlet of the Green, across farmland or along the ancient drovers' road of Green Lanes, the two places had and still have a close connection. From the mid-1640s to the mid-1650s, Stoke Newington's parish church was led by Thomas Manton, "a principal person among the non-conformist ministers",;[20] a staunch and popular defender of Reformed principles, he participated in the Westminster Assembly, acted as chaplain to Oliver Cromwell, and preached before Parliament on several occasions. Another Dissenting meeting house was built in Stoke Newington about 1700, near the house of Mary Abney, who had inherited the manor.[21] Later that century the village became known for its Quaker inhabitants; their meeting house was designed by the architect William Alderson.[22] In 1858 the medieval parish church of St Mary was supplemented by an impressive Victorian Gothic building opposite, by Sir George Gilbert Scott.[17] In addition to the buildings, Stoke Newington was remarkable for its range of social reforms, from its connections to the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade to the foundation of the innovative Newington Academy for Girls.

As the NGUC lacks its own cemetery, some of its congregants, such as the poet and banker Samuel Rogers, are buried in St Mary's churchyard. However, as the Church of England normally limits its cemeteries to its members, most of the Newington Green Unitarians opted for Bunhill Fields until the middle of the 19th century, and then Abney Park Cemetery thereafter. (Robert Southey called the former the Campo Santo of the Dissenters, but the phrase was used for both.) Wollstonecraft was married and later buried at St Pancras Old Church a few miles away.

Earliest years: to the mid-eighteenth century

Newington Green Unitarian Church has been associated with many historically significant people on both sides of the pulpit, especially but not exclusively in the eighteenth century. Charles Morton (1626–1698), the great educator who ended his career as vice-president of Harvard University, ran an influential Dissenting Academy, "probably on the site of the current Unitarian church".[23] One of his friends, James Ashurst, founded a group that worshipped in private houses licensed for the purpose, and, in time, this small congregation decided to build a proper meeting house.[10] (It is worth mentioning here the early religious evolution of this church. It started as Presbyterian, with views on the Trinity as orthodox as those held by the Church of England. In fact, several of its first ministers chose to conform, i.e. rejoin, the established church:[24] one of these was Richard Biscoe, who gave the Boyle Lectures in the late 1730s. However, NGUC soon acquired ministers who were Arian, that is, who denied the Trinity, although they retained their belief in the divinity of Jesus Christ.[25] Thus was the Unitarian nature of the church created. In the mid-nineteenth century it was described by a local historian as a Socinian Independent meeting house.[26]) The author Daniel Defoe, who attended school at Newington Green, is believed to have attended the church.[27] Isaac Watts, the "Father of English Hymnody", theologian, logician, and educator, was brought up as a non-Conformist, lived from 1736 to 1748 at Abney Park nearby, and during that period "was known to have adopted decidedly Unitarian opinions", so he too may have attended NGUC.[28] Samuel Wright, son of a nonconformist minister in Nottinghamshire, writer on theological issues and "a very eminent divine among the Presbyterians" lived at Newington Green until his death in 1746.[29] Several of the church's ministers were at the same time, or had been, the librarians at the theological collection known as Dr Williams's Library, an establishment still very much alive.

Later eighteenth century: the voices heard round the world

Richard Price

The minister whose name is still remembered centuries later is Dr Richard Price, a libertarian and republican who cemented the village's "reputation as a centre for radical thinkers and social reformers".[30] He arrived in 1758 with his wife Sarah, and took up residence in No. 54 the Green, in the middle of a terrace even then a hundred years old. (The building still survives as London's oldest brick terrace, dated 1658.) In that house, or the church, he was visited by Founding Fathers of the United States such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Paine; other American politicians such as John Adams, who later became the second president of the United States, and his wife Abigail; British politicians such as Lord Lyttleton, the Earl of Shelburne, Earl Stanhope (known as "Citizen Stanhope"), and even the Prime Minister William Pitt; philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith; agitators such as prison reformer John Howard, gadfly John Horne Tooke, and husband and wife John and Ann Jebb, who between them campaigned on expansion of the franchise, opposition to the war with America, support for the French Revolution, abolitionism, and an end to legal discrimination against Roman Catholics; writers such as poet and banker Samuel Rogers;[31] and clergyman-mathematician Thomas Bayes, known for Bayes' theorem.

Price was fortunate in forming close friendships among his neighbours and congregants. One was Thomas Rogers, father of the above, a merchant turned banker who had married into a long-established Dissenting family and lived at No. 56 the Green. More than once, Price and the elder Rogers rode on horseback to Wales.[31] Another was the Rev. James Burgh, author of The Dignity of Human Nature and Thoughts on Education, who opened his Dissenting Academy on the green in 1750 and sent his pupils to Price's sermons.[13] Price, Rogers, and Burgh formed a dining club, eating at each other's houses in rotation.[32] When in 1770 Price became morning preacher at the Gravel Pit Chapel in Homerton, he continued his afternoon sermons at NGUC.

There were many at a distance who acknowledged their debt to Price, such as the Unitarian theologians William Ellery Channing and Theophilus Lindsey, and the formidable polymath and Dissenting clergyman, Joseph Priestley, discoverer of oxygen. When Priestley's support of dissent led to the riots named after him, he fled Birmingham and headed for the sanctuary of Newington Green, where Rogers took him in.

The support Price gave to the revolt of the colonies of British North America, arguing that the American Revolution was justified, made his name as a famous or notorious preacher. He rejected traditional Christian notions of original sin and moral punishment, preaching the perfectibility of human nature,[33] and he wrote on theological questions. However, his interests were wide-ranging, and during the decades Price spent as minister of NGUC, he also wrote on finance, economics, probability, and life insurance, being inducted into the Royal Society in recognition of his work. On the 101st anniversary of the Glorious Revolution, he preached a sermon titled "A Discourse on the Love of Our Country", thus igniting a so-called "pamphlet war" known as the Revolution Controversy, furiously debating the issues raised by the French Revolution. Burke's rebuttal "Reflections on the Revolution in France" attacked Price, whose friends Paine and Wollstonecraft leapt into the fray to defend their mentor. The reputation of Price for speaking without fear of the government on these political and philosophical matters drew huge crowds to the church, and were published and sold as pamphlets (i.e. publications easily printed and circulated).

Mary Wollstonecraft

One of the congregants Price most influenced was the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who moved her fledgling school for girls from Islington to the Green in 1784, with the help of a "fairy godmother"[34] whose good auspices found her a house to rent and 20 students to fill it.[35] Her patron — or matron — was the well-off Mrs Burgh, widow of the educationalist, who treated her almost as a daughter.[36] The new arrival attended services at NGUC: she was a lifelong Anglican, but, in keeping with the church's and Price's ethos of logical enquiry and individual conscience, believers of all kinds were welcomed without any expectation of conversion.[37] The approach of these Rational Dissenters appealed to Wollstonecraft: they were hard-working, humane, critical but uncynical, and respectful towards women,[38] and in her hour of need proved kinder to her than her own family.[37] She, an unmarried woman making her own way in the world, was marginal to the dominant society in just the same way that the Dissenters were.[39]

Wollstonecraft was then a young schoolmistress, as yet unpublished, but Price saw something in her worth fostering, and became a friend and mentor. Through the minister (and through the young Anglican John Hewlett,[40] who also introduced her to the eminent lexicographer Samuel Johnson[41]), she met the great humanitarian and radical publisher Joseph Johnson, who was to guide her career and serve as a father figure. Through him, with a title alluding to the husband of her other benefactor, she published Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (subtitled: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life). The ideas Wollstonecraft ingested from the sermons at NGUC pushed her towards a political awakening.[42] A couple of years after she had had to leave Newington Green, these seeds germinated into A Vindication of the Rights of Men, a response to Burke's denunciation of the French Revolution and attack on Price. In 1792 she published the work for which she is best remembered, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, in the spirit of rationalism extending Price's arguments about equality to women: Her biographer Claire Tomalin argues that just as the Dissenters were "excluded as a class from education and civil rights by a lazy-minded majority", so too were women, and the "character defects of both groups" could be attributed to this discrimination.[43] A commemorative mural dedicated to Wollstonecraft stands in the church, which has been described as "the birthplace of feminism".[44]

Joseph Towers

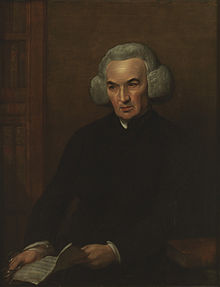

It would have been hard for anyone to step into the shoes of Dr Price, but the minister from 1778 to his death in 1799 was a remarkable character in his own right. Joseph Towers was born in about 1738, the son of a poor bookseller, and was apprenticed as a printer to Robert Goadby of Sherborne. Lacking formal education, he read all he could and educated himself, eventually writing learned works such as Criminal Libel and the Duty of Juries, and being awarded a Doctor of Law degree by Edinburgh University. Towers assisted fellow minister Andrew Kippis in developing the Biographia Britannica, a forerunner of the Dictionary of National Biography. He was secretary of the highly respectable Society for Constitutional Information, which lobbied for political liberties, but it was suppressed by the authorities, who lived in fear of the Reign of Terror crossing the Channel. Towers was put under arrest until the Archbishop of Canterbury intervened on his behalf.[45]

Early 19th century: The Barbaulds

In 1808, Rochemont Barbauld was appointed minister, first as the morning preacher. His wife, Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743–1825), was a prolific writer, admired by Samuel Johnson and William Wordsworth.[46] She enjoyed a long friendship with Joseph Priestley and William Enfield, starting from their years together at the Warrington Academy in the 1760s, where her father John Aikin was tutor. She wrote poems (including a tribute to Priestley), hymns, children's literature, and political and religious tracts. She was an abolitionist, addressing one of her works to William Wilberforce. In 1793 she contributed to the Pamphlet War, "Sins of the Government, Sins of the Nation". Two years later she wrote The Rights of Women, but it was not published until her death 30 years later.

Rochemont eventually went violently insane, attacked his wife, and committed suicide by drowning himself in the New River that runs through Islington. Anna remained a member of the congregation until her death and is commemorated in the church with a plaque which praises her work for "the Cause of Humanity, Peace, and Justice, [and] of Civil and Religious Liberty". Her brother Dr John Aikin lived nearby, and together they co-authored books such as Evenings at Home. As he had been a Unitarian minister in his youth, it is likely that he worshipped at NGUC, with his son Arthur, a prominent scientist, and his daughter Lucy, a biographer. They lived in a house previously occupied by Adam Anderson, clerk to the South Sea Company.[47]

Early 19th century: legal acceptance

Thomas Rees took over after Barbauld's death. He was a leading authority of the history of Unitarianism, and made connections with the Unitarian Church of Transylvania. In 1813 two things occurred, key to the understanding of the development of the church: Parliament passed the Doctrine of the Trinity Act, and Rees was succeeded by James Gilchrist, who remained for 15 years. (His son Alexander wrote the standard biography of poet and artist William Blake.) The larger public event meant that the civil and religious liberties that Dissenters had been fighting for were won, the battle of a century and a half was over. The more particular event sowed its own seeds of destruction, as Gilchrist gradually changed his opinions and eventually wrote a pamphlet called "Unitarianism Abandoned", which infuriated his very Unitarian congregation. For a long time he refused to resign, but in the end he was forced out, and the church built a safeguard against such a future occurrence by holding annual elections for the minister. NGUC then entered a very low ebb, with at one point as few as nine subscribers and a rapid turnover of ministers. The causes it had agitated for had been successful, and the church looked backwards with pride, but saw little to look forward to. Energy drained away. "Legal recognition did not prosper the cause of the church, however, which at this time began to decline."[48]

Mid-19th century: social challenges

"New causes and fresh ideals were needed to revitalise the church, and, fortunately, they were forthcoming." The nature of Newington Green had changed—the fresh bucolic village had been swallowed up by London's relentless growth, and had become a "thriving and expanding suburb".[49] With this growth of prosperity also came a tide of poverty,[16] and this was to prove the mission for the Victorian era. A hundred years before, the ethos had been one of almost Puritan self-reliance, but now the Dickensian poverty, evident in cholera epidemics and rampant malnutrition, made social responsibility an urgent necessity.[50] The minister who guided the first 25 years of this (1839–64) was Thomas Cromwell, FSA (1792–1870). (Like many Anglican vicars,[51] one of his hobbies was local history.)

A charity school for 14 girls and a monitorial Sunday school for 150 children had been set up in the vicinity by Dissenters in 1790 and 1808 respectively, but these efforts were augmented in the middle of the century.[52] In 1840, a Sunday school was set up for poor children, and soon thereafter a Domestic Mission Society, to visit the poor in their homes. A library and a savings club emphasised self-help. A regular day school ran from 1860 for ten years, until primary education became the responsibility of the state with the passing of the Elementary Education Act 1870.

One of the first actions of Cromwell's tenure, in terms of changing the church services, was to introduce the hymnbook of James Martineau. Samuel Sharpe, named after his uncle, the poet Samuel Rogers, came to Newington Green in 1828, and maintained his connection for 30 years, including as trustee. He was an erudite and generous man, a banker by day and an Egyptologist and Bible translator in his leisure hours.[53] In 1870 he was elected Chairman of the British and Foreign Unitarian Society. Andrew Pritchard (1804–1882) was treasurer of NGUC 1850–73, during which time donations doubled. He was a microscope and slide maker who made significant improvements to microscopy and studied microscopic organisms; he was a friend of Michael Faraday and for him, science and religion were one. He led the Newington Green Conversation Society, membership restricted to 16, a successor to the Mutual Instruction Society.[54] The "small but energetic community" continued to campaign on the larger political stage, presenting petitions to Parliament on subjects touching religious matters, such as the Dissenting Chapels Bill (made law as Nonconformists Chapels Act 1844), the removal of civil disabilities from the Jews (1847), permission for Dissenters to attend Oxford and Cambridge Universities, and the revision of the King James Bible.[55] Religious freedom and self-improvement were their watchwords.

Later 19th century: towards the high water

NGUC thrived during the last decades of the 19th century, and its congregation grew to 80 subscribers. The London Sunday School Society recognised the one at NGUC as the best in its class, educating up to 200 children and necessitating the construction in 1887 of the schoolhouse immediately behind the main church building. A range of groups sprung up, ranging from intellectual (a Society for Mutual Theological Study) to recreational (cycling and cricket). Young Men's and Young Women's groups met, as did the Mothers' Meeting, a Provident Society, and teetotalism (abstinence from alcohol) support for adults and children. Other issues of concern were education, social reform, and women's suffrage.

Sister and brother Marian and Ion Pritchard continued the work of their father. The cause of liberal religion in general, and the development of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, were overarching themes. Marian in particular is described as an unsung heroine, and "one of the leaders of modern Unitarianism". She set up Oxford Summer Schools for the training of Sunday School teachers, and Winifred House Invalid Children's Convalescent Home.[56]

Early to mid 20th century: wars and crises

Thorncroft, author of the church's semiquincentennial history, Trust in Freedom, concludes that NGUC reached its high-water mark at its bicentenary in 1908. Immediately after this, NGUC suffered a religious schism in miniature, when the incoming minister, Dr F. W. G. Foat, backed the New Theology of Reginald John Campbell and the League of Progressive Thought and Service. This Social Gospel movement was not to the taste of all his congregants, and Foat left for the Richmond Free Christian Church. Then came 1914, and Christian faith all over the world was shaken by the horrors of World War I. Unitarians as a body have never been pacifists, unlike the Quakers, and some fifteen members of the congregation and Sunday School fell during the war. Society as a whole found less solace in religion, perhaps particularly liberal religion, with its message of human dignity ringing hollow beside the great guns. Meanwhile, many of the older people with long family ties to Newington Green simply died. The professional middle class had largely left the area. Numbers in the pews dropped. By 1930 "it was whispered that the church could not survive".[57]

One influential supporter was an alderman and councillor in the Borough of Stoke Newington, and in 1938 a new lay pastor and his family breathed new life into the church. Although attendance at services was low, other activities drew in crowds: 100 to the temperance meetings, for example. The outbreak of World War II meant that children were evacuated temporarily from London, so the Sunday Schools and Young People's Leagues ceased for a time. The Sunday services never missed a week, however, even when the building was badly damaged by a landmine blast: they just moved to the schoolhouse. After the war, the ministry focused on building bridges between races and faiths, e.g. with the Jewish community of North London, and was recognised by the World Congress of Faiths, an organisation founded by Francis Younghusband. Services were often attended by local politicians, including the Mayor of Stoke Newington. Leaders for the national Unitarian movement continued to be found within the congregation at Newington Green.[58]

In the mid-20th century, the building was damaged by German bombing. In 1953 its architectural importance was recognised as a Grade II listed building.[59]

Later 20th century/early 21st century: rejuvenation

In the late 20th century, faced with declining numbers, Newington Green Unitarian Church developed closer ties with Islington Unitarian Church a couple of kilometres away. They started to share a minister and publicise events together under the name New Unity, while remaining legally distinct entities. The 1969 sale of the (New) Gravel Pit Chapel near the centre of the historic village of Hackney released funding via the Charity Commission for maintenance of the Newington Green chapel.[60]

By the turn of the millennium, NGUC's community was reduced in numbers. A small congregation of half a dozen elderly women persisted,[61] and a new burst of energy arrived with the appointment of Cathal (Cal) Courtney, first as student pastor in 2002 and then as minister in July 2004.[62] He came from an Ireland of divided communities;[63] he was characterised as a "radical spirit" who had made a "remarkable spiritual journey", and his weekly sermons soon attracted twenty people.[64] In the tradition of Unitarian social action, he led a silent vigil through the night before the huge march against the Iraq War, "protesting against the US-led incursion with, among others, Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists and Jews present"[64] Later made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, during his time at NGUC he wrote Towards Beloved Community and was written about as the Right-On Reverend in The Oldie's monthly "East of Islington" column.[65]

The incumbent is Andrew Pakula, an American who grew up in a Jewish family in New York.[66] His MIT doctorate in biology and master's degree in business led to his first career in biotechnology management and business development, before he undertook ministerial training, completing his studies at Unitarian College, Manchester.[67] He began serving in October 2006,[68] was inducted as full minister in January 2010,[69] and was elected to the executive committee of the British Unitarians.[70] He was described – sympathetically – in the local press as "controversial" when he did a reverse collection plate, giving his own money away to those attending one sermon.[71]

A large-scale renovation was completed in 2020, funded by a £1.73 million grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Subsequently, the building was removed from the Heritage at Risk Register.[44] The church brands itself as a non-religious, New Unity, group explaining this as "New Unity is committed to equality between people of all genders and fully embraces LGBTQ+ people. There is no set of mandatory beliefs; people have the right and responsibility to think for themselves."[44][72]

Richard Price Memorial Lecture

Courtney revived the Richard Price Memorial Lecture, which had last been given in 1981.[64] NGUC now sponsors it annually, to address "a topical or important aspect of liberty, reason and ethics".[73] In September 2003 the first of the new series took place under the auspices of the Stoke Newington Unitarian Conference, where Barbara Taylor, author of Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination, spoke on "Radical Dissent and Women's Rights in Eighteenth-Century Britain".[74] In 2005 Will Self addressed the need to disestablish the Church of England [75] under the title "Why Religion Needs Satire". The November 2008 lecture took the theme of "Dishonesty": Evan Davis, the economist and BBC presenter, used the platform to argue that "the media industry has a 'misleading ethical code' and tendency to be dishonest".[76] The 2009 lecture, given on 27 January 2010, was given by psychotherapist Susie Orbach, who spoke on the topic "Frankenstein's Bodies Today".[77] The 2010 lecture was given by literary critic Terry Eagleton, who spoke on "The New Atheism and the War on Terror".[78] In 2011 Wendy Savage, a doctor and long-time campaigner for women's reproductive health, spoke on " Patients' Choice and Doctors' Responsibilities".[79]

Stance on gay marriage

In March 2008, Newington Green Unitarian Church became the first religious establishment in Britain to refuse to carry out any weddings at all until all couples have equal marriage rights.[80] Unity Church Islington followed suit a couple of months later. Pakula stated that same-sex couples "are being treated like second-class citizens when they are forbidden to celebrate their unions in a way that heterosexual couples take for granted".[81] The BBC called it a "gay rights church" for its unanimous committee vote suspending full wedding services,[82] although NGUC is not a "gay church" such as the Metropolitan Community Church, and it still conducts ceremonial blessings of relationships, straight and gay. The church's decision was in response to the case brought by the Christian Institute, backing the claim of Lillian Ladele, a registrar employed by Islington London Borough Council who wished to be exempted from having to perform civil partnership ceremonies on the grounds of her religion.[83] The move was praised by Rev. Richard Kirker, chairman of the national Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement. "This is the first church I’ve heard of to have taken this step", he said. "We’re proud that Islington is striking a blow for human rights."[81] Following in the steps of his immediate predecessor, who used his inaugural column in the N16 magazine to address the international furore around Gene Robinson's election as bishop,[84] Pakula sees homophobia as the real problem, and his congregation did consider challenging the law under the European Convention on Human Rights.[66] Human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell called on the church to conduct a gay marriage in defiance of the law.[61]

Tercentenary celebrations

NGUC celebrated its tercentenary in 2008 under the slogan "300 years of dissent", marking this with events such as planting a crab apple tree,[85] organising a picnic in conjunction with the Newington Green Action Group, and hosting a concert of Ottoman classical music.[86] (There is a strong Turkish community in Newington Green and along the nearest section of Green Lanes, an ancient road which starts from the northwest corner of the Green.)

250th anniversary of Wollstonecraft's birth

The following year it commemorated the 250th anniversary of the birth of Mary Wollstonecraft,[87] attaching a large banner to the railings outside the building, proclaiming it the "birthplace of feminism", in a nod to the formative years that she spent worshipping there.[83] NGUC sponsored a series of events,[88] including a return visit and lecture by biographer Barbara Taylor; a panel discussion about women and power, between female politicians Diane Abbott MP, Jean Lambert MEP, and Emily Thornberry MP;[89] an art exhibition titled Mother of Feminism; a concert featuring Carol Grimes and Adey Grummet, to raise money for Stop the Traffik, an anti-trafficking charity; a tombstone tribute at St Pancras Old Church; a birthday cake baked by men; and other activities.[90]

Pakula's sermon in honour of the Wollstonecraft anniversary stressed her role as a prophet. This excerpt serves as a flavour of the emphasis given to social action within the church:[91]

Mary Wollstonecraft was a unique individual – brilliant and strong. She was one who would not be swept along in stream of the common beliefs and understandings of her time. Hers was a keener sight – a vision that saw beyond what most people take for granted. She saw, contrary to the assumptions of her time, that women were the equals of men. Her bold stance – a position that proved to be many years ahead of her time – was met with broad condemnation. Today, we recognise that Mary Wollstonecraft spoke with the voice of prophesy. We honour her for her courage and for the gifts she has given to future generations of women and men.

Regular and occasional activities

Services occur every Sunday at Newington Green Unitarian Church and include special events such as the yearly Flower Communion; twice-monthly poetry readings and weekly meditation sessions are also held at NGUC. It participates in the annual festival of architecture, Open House London. It hosts occasional concerts, such as that given by the London Gallery Quire, which "performs West Gallery Music, the psalmody heard in parish churches and non-conformist chapels during the Georgian period, from about 1720 to 1850",[92][93] and the Psallite Women's Choir.[94] The congregation was reported to have grown to 70 as of 2009,[61] with 30 at one Sunday service;[71] it is one of the most rapidly growing Unitarian churches in Britain.[69]

References

- ^ Morris, Hugh (21 October 2016). "London Zoo's aviary and the birthplace of feminism among sites at risk". Daily Telegraph.

- ^ page 4. Thorncroft, Michael (1958). Trust in Freedom: The Story of Newington Green Unitarian Church 1708–1958. London: Private publication for the trustees of the church. p. 35.

- ^ Thorncroft p5

- ^ "Spirit of the Age" by Tom Paulin. 5 April 2003 The Guardian

- ^ Tomalin, Claire (1992). The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (rev. ed. 1992). London: Penguin Books. p. 46. ISBN 9780140167610.

- ^ Jacobs, Diane (2001). Her Own Woman: The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. London: Simon & Schuster. pp. 334. Page 38. ISBN 9780684810935.

- ^ Gordon, Lyndall (2005). Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. Virago Press. pp. 562. Page 42.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). London 4: North. Buildings of England. Yale University Press. p. 536. ISBN 0300096534.

- ^ a b Thorncroft, p8

- ^ History and Topoography of the Parish of St Mary, Islington by Samuel Lewis, 1842, cited in Allardyce, p9.

- ^ "Hackney - Archives and local history". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ a b Gordon, p42.

- ^ Jacobs, p38-39.

- ^ Allardyce, p35.

- ^ a b Allardyce, p33.

- ^ a b 'Stoke Newington: Churches', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 8: Islington and Stoke Newington parishes (1985), pp. 204–211. Accessed 29 May 2009.

- ^ Allardyce, p39.

- ^ Allardyce, p36.

- ^ Robinson, p141.

- ^ Robinson, William (1842). The history and antiquities of the parish of Stoke Newington in the county of Middlesex: containing an account of the prebendal manor, the church, charities, schools, meeting houses, &c., with appendices. J.B. Nichols and Son. pp. 215, 296.

- ^ "Quakers around Shoreditch and life around Bunhill". Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Allardyce, p7.

- ^ Thorncroft, ch.3 "The Early Years: 1714–1758"

- ^ Thorncroft, p11

- ^ Robinson, p210.

- ^ "Defoe in Stoke Newington". Arthur Secord, P.M.L.A. Vol. 66, p. 211, 1951. Cited in Thorncroft, p9, who identifies him as "an American scholar".

- ^ Thorncroft, p10.

- ^ 'Stoke Newington', The Environs of London: volume 3: County of Middlesex (1795), pp. 280–305. Accessed 31 May 2009.

- ^ Allardyce, p18.

- ^ a b Thorncroft, p15.

- ^ Allardyce, p23.

- ^ Gordon, p50.

- ^ Gordon, p40.

- ^ Jacobs, p38.

- ^ Gordon, p46.

- ^ a b Tomalin, p60.

- ^ Tomalin, p51.

- ^ Gordon, p48.

- ^ Jacobs, p45.

- ^ Tomalin, p50 and 57

- ^ Gordon, p51 passim.

- ^ Tomalin, p61.

- ^ a b c Brown, Mark (15 October 2020). "Historic England takes London 'birthplace of feminism' off at-risk list". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Thorncroft, p17-18

- ^ Thorncroft, p19

- ^ Robinson, p91-92.

- ^ Thorncroft, p20 and throughout ch 5, "New Causes for Old".

- ^ Thorncroft, p20.

- ^ Thorncroft, p2-23.

- ^ cf William Bedwell (1561–1632), nearby Vicar of Tottenham, and W.A. Diggens, Vicar of St Keverne, Cornwall 1896–1913 Index

- ^ Robinson, p209.

- ^ Clayden, PW (1883). Samuel Sharpe. p. 82. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ Thorncroft, p23-24.

- ^ Thorncroft, p25.

- ^ Thorncroft, p28, and throughout ch7 "The Lights Go Out".

- ^ Thorncroft, p31.

- ^ Thorncroft, p32-33.

- ^ Historic England. "Unitarian Chapel, Newington Green (Grade II) (1235210)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ T.F.T. Baker, ed. (1995). "Hackney: Protestant Nonconformity". A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 10: Hackney. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ a b c "It's time for Unitarians to break the law on marriage" Islington News 20 Nov 2009

- ^ "Lantern April 2005. London District Unitarian newsletter" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ^ Richards, Mandy (20 April 2005). "Gentrification: how was it for you?". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c N16 magazine, issue 18 (Summer 2003) Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Photo and brief biography as part of interview. "Dissent in Newington Green" by Rab MacWilliam

- ^ Courtney, Cathal (2 April 2007). Towards Beloved Community. Exposure Publishing. ASIN 1846856612.

- ^ a b "Church minister: homophobia is the real sin"[permanent dead link] by Katrina Bishop. 18 March 2009 Islington Now

- ^ Self-provided biographical information on Unitarian.org.uk[permanent dead link]

- ^ ""Vandals at the chapel" N16 magazine Winter 2006". Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Church welcome for new minister" Hackney Gazette 21 January 2010 page 8

- ^ Commissions and Panels – Executive Committee Archived 6 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b ‘Help yourselves to the collection plate’ 24 October 2008 Islington News

- ^ "Non-religious Church". New Unity. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ ""Dishonesty" Evan Davis". Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "University of East London - UEL - University of East London". Archived from the original on 2 May 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "The soggy wafer of meekness is backed up by air strikes" 28 November 2005 The Independent

- ^ "Media has 'misleading ethical code', says Evan Davis" Archived 26 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine 14 November 2008 by Katrina Bishop on Journalism.co.uk

- ^ [1] 8 January 2010 Hackney Citizen

- ^ [2] 29 August 2010 Hackney Citizen

- ^ "Debunking Lansley: on patient choice and the NHS reforms". Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "Radicalism and Richard Price" by Rhasan Brunner, in Newington Green Now and Then: N16 magazine, December 2008[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The Church Where You Can't Marry" 4 April 2008 Islington Tribune

- ^ "Gay rights church bans weddings". 8 April 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2016 – via bbc.co.uk.

- ^ a b "Strength in Unity?" by Judith Evans. 19 March 2009 The Guardian

- ^ "Christian charity?" Archived 29 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Cal Courtney. Spring 2005. N16 magazine.

- ^ 25 Feb 2009 Newington Green Action Group Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Home". Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "Festival for ‘first feminist’" by Peter Gruner, 17 April 2009, Islington Tribune

- ^ "Home". Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "Right, so just what do you do all day?" by Aida Edemariam, 19 May 2009 The Guardian

- ^ "Birthplace of Feminism" by Guy Bentham, in N16, issue 41, spring 2009

- ^ "Prophetic Mary" New Unity website. For 26 April 2009. Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "London Gallery Quire - Welcome". Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ 20 Sept 2008 Newington Green Action Group Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 4 Oct 2008 Newington Green Action Group Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- The Village that Changed the World: A History of Newington Green London N16 by Alex Allardyce. Newington Green Action Group: 2008.

- Chapter titles: Beginnings, Kings and Treason; Dissenters, Academies and Castaways; The Chaste Old Bachelor of Newington Green; Enlightenment, Revolutions and Poets; Development, Destruction and Renewal.

- Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft by Lyndall Gordon. Little, Brown: 2005.

- Her Own Woman: The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft by Diane Jacobs. Simon & Schuster: 2001.

- Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination by Barbara Taylor. CUP: 2003.

- Trust in Freedom: The Story of Newington Green Unitarian Church 1708–1958 by Michael Thorncroft. Privately printed for church trustees, 1958. Full text on church website here.

- Chapter titles: The Fertile Soil; The Church is Built; The Early Years (1714–1758); The Age of Richard Price; New Causes for Old; The Ideal of Service; The Lights Go Out; The Present Day.

- The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft by Claire Tomalin. Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1974.

External links

- Use dmy dates from September 2013

- 18th-century Protestant churches

- Unitarian chapels in England

- Chapels in London

- Churches in the London Borough of Hackney

- Grade II listed churches in London

- 1708 establishments in England

- Religious organizations established in 1708

- Churches completed in 1708

- Churches completed in 1860

- 19th-century churches in the United Kingdom

- Anna Laetitia Barbauld

- Grade II listed buildings in the London Borough of Hackney