Ore

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

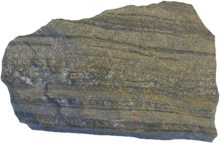

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically containing metals, that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.[1][2] Ore is extracted from the earth through mining and treated or refined, often via smelting, to extract the valuable metals or minerals.[3] The grade of ore refers to the concentration of the desired material it contains. The value of the metals or minerals a rock contains must be weighed against the cost of extraction to determine whether it is of sufficiently high grade to be worth mining, and is therefore considered an ore.[3]

Minerals of interest are generally oxides, sulfides, silicates, or native metals such as copper or gold. Ores must be processed to extract the elements of interest from the waste rock. Ore bodies are formed by a variety of geological processes generally referred to as ore genesis.

Ore, gangue, ore minerals, gangue minerals

In most cases, an ore does not consist entirely of a single ore mineral but it is mixed with other valuable minerals and with unwanted or valueless rocks and minerals. The part of an ore that is not economically desirable and that can not be avoided in mining is known as gangue.[1][2] The valuable ore minerals are separated from the gangue minerals by froth flotation, gravity concentration, and other operations known collectively as mineral processing[4] or ore dressing.[5]

Ore deposits

An ore deposit is an economically significant accumulation of minerals within a host rock. This is distinct from a mineral resource as defined by the mineral resource classification criteria. An ore deposit is one occurrence of a particular ore type.[6] Most ore deposits are named according to their location, or after a discoverer (e.g. the Kambalda nickel shoots are named after drillers),[7] or after some whimsy, a historical figure, a prominent person, a city or town from which the owner came, something from mythology (such as the name of a god or goddess)[8] or the code name of the resource company which found it (e.g. MKD-5 was the in-house name for the Mount Keith nickel sulphide deposit).[9]

Classification

Ore deposits are classified according to various criteria developed via the study of economic geology, or ore genesis. The classifications below are typical.

Hydrothermal epigenetic deposits

- Mesothermal lode gold deposits, typified by the Golden Mile, Kalgoorlie

- Archaean conglomerate hosted gold-uranium deposits, typified by those at Elliot Lake, Ontario, Canada and Witwatersrand, South Africa

- Carlin–type gold deposits, including;

- Epithermal stockwork vein deposits

Granite related hydrothermal

- IOCG or iron oxide copper gold deposits, typified by the supergiant Olympic Dam Cu-Au-U deposit

- Porphyry copper +/- gold +/- molybdenum +/- silver deposits

- Intrusive-related copper-gold +/- (tin-tungsten), typified by the Tombstone, Arizona deposits

- Hydromagmatic magnetite iron ore deposits and skarns

- Skarn ore deposits of copper, lead, zinc, tungsten, etcetera

Magmatic deposits

- Magmatic nickel-copper-iron-PGE deposits including

- Cumulate vanadiferous or platinum-bearing magnetite or chromite

- Cumulate hard-rock titanium (ilmenite) deposits

- Komatiite hosted Ni-Cu-PGE deposits

- Subvolcanic feeder subtype, typified by Noril'sk-Talnakh and the Thompson Belt, Canada

- Intrusive-related Ni-Cu-PGE, typified by Voisey's Bay, Canada and Jinchuan, China

- Lateritic nickel ore deposits, examples include Goro and Acoje, (Philippines) and Ravensthorpe, Western Australia.

Volcanic-related deposits

- Volcanic hosted massive sulfide (VHMS) Cu–Pb–Zn including;

- Examples include Teutonic Bore and Golden Grove, Western Australia

- Besshi type

- Kuroko type

- Examples include Teutonic Bore and Golden Grove, Western Australia

Metamorphically reworked deposits

- Podiform serpentinite-hosted paramagmatic iron oxide-chromite deposits, typified by Savage River, Tasmania iron ore, Coobina chromite deposit

- Broken Hill Type Pb–Zn–Ag, considered to be a class of reworked SEDEX deposits

Carbonatite-alkaline igneous related

- Phosphorus-tantalite-vermiculite (Phalaborwa South Africa)

- Rare-earth elements – Mount Weld, Australia and Bayan Obo, Mongolia

- Diatreme hosted diamond in kimberlite, lamproite or lamprophyre

Sedimentary deposits

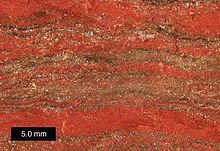

- Banded iron formation iron ore deposits, including

- Channel-iron deposits or pisolite type iron ore

- Heavy mineral sands ore deposits and other sand dune hosted deposits

- Alluvial gold, diamond, tin, platinum or black sand deposits

- Alluvial oxide zinc deposit type: sole example Skorpion Zinc

Hydrothermal deposits formed largely from basinal brines

Hydrothermal deposits formed by basinal saline fluids, include the following main groups:[10]

- Clastic hosted or SEDEX Lead-zinc-silver deposits. They are typified, among others, by Red Dog, McArthur River, Mount Isa, Rammelsberg.[11]

- Mississippi valley type (MVT) zinc-lead deposits[11]

- Sediment-hosted stratiform Cu-Co-(Ag) deposit, typified by the Copperbelt of Zambia and DRC.[12]

Astrobleme-related ores

- Sudbury Basin nickel and copper, Ontario, Canada

Extraction

The basic extraction of ore deposits follows these steps:

- Prospecting or exploration to find and then define the extent and value of ore where it is located ("ore body").

- Conduct resource estimation to mathematically estimate the size and grade of the deposit.

- Conduct a pre-feasibility study to determine the theoretical economics of the ore deposit. This identifies, early on, whether further investment in estimation and engineering studies is warranted and identifies key risks and areas for further work.

- Conduct a feasibility study to evaluate the financial viability, technical and financial risks and robustness of the project and make a decision as whether to develop or walk away from a proposed mine project. This includes mine planning to evaluate the economically recoverable portion of the deposit, the metallurgy and ore recoverability, marketability and payability of the ore concentrates, engineering, milling and infrastructure costs, finance and equity requirements and a cradle to grave analysis of the possible mine, from the initial excavation all the way through to reclamation.

- Development of access to an ore body and building of mine plant and equipment.

- The operation of the mine in an active sense.

- Reclamation to make land where a mine had been suitable for future use.

Trade

Ores (metals) are traded internationally and comprise a sizeable portion of international trade in raw materials both in value and volume. This is because the worldwide distribution of ores is unequal and dislocated from locations of peak demand and from smelting infrastructure.

Most base metals (copper, lead, zinc, nickel) are traded internationally on the London Metal Exchange, with smaller stockpiles and metals exchanges monitored by the COMEX and NYMEX exchanges in the United States and the Shanghai Futures Exchange in China.

Iron ore is traded between customer and producer, though various benchmark prices are set quarterly between the major mining conglomerates and the major consumers, and this sets the stage for smaller participants.

Other, lesser, commodities do not have international clearing houses and benchmark prices, with most prices negotiated between suppliers and customers one-on-one. This generally makes determining the price of ores of this nature opaque and difficult. Such metals include lithium, niobium-tantalum, bismuth, antimony and rare earths. Most of these commodities are also dominated by one or two major suppliers with >60% of the world's reserves. The London Metal Exchange aims to add uranium to its list of metals on warrant.

The World Bank reports that China was the top importer of ores and metals in 2005 followed by the US and Japan.[13][citation needed]

Important ore minerals

- Acanthite (cooled polymorph of Argentite): Ag2S for production of silver

- Barite: BaSO4

- Bauxite Al(OH)3 and AlOOH, dried to Al2O3 for production of aluminium

- Beryl: Be3Al2(SiO3)6

- Bornite: Cu5FeS4

- Cassiterite: SnO2

- Chalcocite: Cu2S for production of copper

- Chalcopyrite: CuFeS2

- Chromite: (Fe, Mg)Cr2O4 for production of chromium

- Cinnabar: HgS for production of mercury

- Cobaltite: (Co, Fe)AsS

- Columbite-Tantalite or Coltan: (Fe, Mn)(Nb, Ta)2O6

- Galena: PbS

- Native gold: Au, typically associated with quartz or as placer deposits

- Hematite: Fe2O3

- Ilmenite: FeTiO3

- Magnetite: Fe3O4

- Malachite: Cu2CO3(OH)2

- Molybdenite: MoS2

- Pentlandite: (Fe, Ni)9S8

- Pollucite: (Cs, Na)2Al2Si4O12·2H2O

- Pyrolusite: MnO2

- Scheelite: CaWO4

- Smithsonite: ZnCO3

- Sperrylite: PtAs2 for production of platinum

- Sphalerite: ZnS

- Uraninite (pitchblende): UO2 for production of metallic uranium

- Wolframite: (Fe, Mn)WO4

See also

- Economic geology

- Extractive metallurgy (ore processing)

- Froth Flotation

- Mineral resource classification

- Ore genesis

- Petrology

References

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ore". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 April 2021

- ^ a b Neuendorf, K.K.E., Mehl, J.P., Jr., and Jackson, J.A., eds., 2011, Glossary of Geology: American Geological Institute, 799 p.

- ^ a b Hustrulid, William A.; Kuchta, Mark; Martin, Randall K. (2013). Open Pit Mine Planning and Design. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4822-2117-6. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Drzymała, Jan (2007). Mineral processing : foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy (PDF) (1st eng. ed.). Wroclaw: University of Technology. ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Petruk, William (1987). "Applied Mineralogy in Ore Dressing". Mineral Processing Design: 2–36. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-3549-5_2. ISBN 978-94-010-8087-3.

- ^ Joint Ore Reserves Committee (2012). The JORC Code 2012 (PDF) (2012 ed.). p. 44. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Chiat, Josh (10 June 2021). "These secret Kambalda mines missed the 2000s nickel boom – meet the company bringing them back to life". Stockhead. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Thornton, Tracy (19 July 2020). "Mines of the past had some odd names". Montana Standard. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Dowling, S. E.; Hill, R. E. T. (July 1992). "The distribution of PGE in fractionated Archaean komatiites, Western and Central Ultramafic Units, Mt Keith region, Western Australia". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 39 (3): 349–363. Bibcode:1992AuJES..39..349D. doi:10.1080/08120099208728029.

- ^ Arndt, N. and others (2017) Future mineral resources, Chap. 2, Formation of mineral resources, Geochemical Perspectives, v6-1, p. 18-51.

- ^ a b Leach, D. and others (2010) Sediment-hosted lead-zinc deposits in Earth history. Economic Geology, v. 105, p. 593-625.

- ^ Sillitoe, R.H., Perello, J., Creaser, R.A., Wilton, J., Wilson, A.J., and Dawborn, T., 2017, Reply to discussions of "Age of the Zambian Copperbelt" by Hitzman and Broughton and Muchez et al.:, p. 1–5, doi: 10.1007/s00126-017-0769-x.

- ^ "Background Paper – The Outlook for Metals Markets Prepared for G20 Deputies Meeting Sydney 2006" (PDF). The China Growth Story. WorldBank.org. Washington. September 2006. p. 4. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

Further reading

External links

![]() Media related to Ores at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ores at Wikimedia Commons