Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's Iliad,[1] Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally /pəˈtroʊkləs/; Ancient Greek: Πάτροκλος, romanized: Pátroklos, lit. 'glory of the father') was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later ancient sources) lover of Achilles.

Pronunciation of name

There are at least three pronunciations of the name 'Patroclus' in English.[2] Because the penultimate syllable is light in Latin prose (pă′.trŏ.clŭs), the antepenult was stressed in Latin and would normally be stressed in English as well, for /ˈpæ.trə.kləs/ (analogous to 'Sophocles').[3] However, this pronunciation is seldom encountered: for metrical convenience, Alexander Pope had made the 'o' long, and thus stressed, in his translation of Homer, following a convention of Greek and Latin verse, and that pronunciation – of Latin pa.trō′.clus – has stuck, for English /pə.ˈtroʊ.kləs/.[4] Moreover, because in prose a penultimate Greco-Latin short o (omicron) would only be stressed in a closed syllable, the penult has sometimes been misanalysed as being closed (*pă.trŏc′.lŭs), which would change the English o to a short vowel: /pə.ˈtrɒk.ləs/.[5]

Description

In the account of Dares the Phrygian, Patroclus was illustrated as ". . .handsome and powerfully built. His eyes were gray. He was modest, dependable, wise, a man richly endowed."[6]

Family

Patroclus was the son of Menoetius by either Philomela[7][8] or Polymele, Sthenele,[9] Periopis,[10] or lastly Damocrateia.[11] His only sibling was Myrto, mother of Eucleia by Heracles.[12] Homer also references Menoetius as the individual who gave Patroclus to Peleus.[13] Menoetius was the son of Actor,[14] king of Opus in Locris by Aegina, daughter of Asopus.

| Relation | Names | Sources | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homer | Pindar | Apollonius | Philocrates | Apollodorus | Plutarch | Hyginus | Eustathius | Tzetzes | ||||

| Iliad | Sch. Il. | Sch. Ody. | Scholia | Scholia | ||||||||

| Parents | Menoetius | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Menoetius and Sthenele | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Menoetius and Philomela or [clarification needed] |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Menoetius and Polymele | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Menoetius and Damocrateia | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Menoetius and Periopis | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Sibling | Myrto | ✓ | ||||||||||

Mythology

Early days

During his childhood, Patroclus had killed another child in anger over a game. Menoetius gave Patroclus to Peleus, Achilles' father, who named Patroclus Achilles' "squire" as Patroclus and Achilles grew up together, and became close friends.[15] Patroclus acted as a male role model for Achilles, as he was both kinder than Achilles and wise regarding counsel.[a][16]

Trojan War

According to the Iliad, when the tide of the Trojan War had turned against the Greeks and the Trojans were threatening their ships, Patroclus convinced Achilles to let him lead the Myrmidons into combat. Achilles consented, giving Patroclus the armor Achilles had received from his father, in order for Patroclus to impersonate Achilles. Achilles then told Patroclus to return after beating the Trojans back from their ships.[17]: 353 b. 16 l. 64–87 Patroclus defied Achilles' order and pursued the Trojans back to the gates of Troy.[18] Patroclus killed many Trojans and Trojan allies, including a son of Zeus, Sarpedon.[17]: 363 b. 16 l. 460 While fighting, Patroclus' wits were removed by Apollo, after which Patroclus was hit by the spear of Euphorbos. Hector then killed Patroclus by stabbing him in the stomach with a spear.[17]: 373 b. 16 l. 804–822

Achilles retrieved his body, which had been stripped of armor by Hector and protected on the battlefield by Menelaus and Ajax.[19] Achilles did not allow the burial of Patroclus' body until the ghost of Patroclus appeared and demanded his burial in order to pass into Hades.[17]: 474 b.23 l. 69–71 Patroclus was then cremated on a funeral pyre, which was covered in the hair of his sorrowful companions. As the cutting of hair was a sign of grief while also acting as a sign of the separation of the living and the dead, this points to how well-liked Patroclus had been.[1]: 561 The ashes of Achilles were said to have been buried in a golden urn along with those of Patroclus by the Hellespont.[20]

Relationship with Achilles

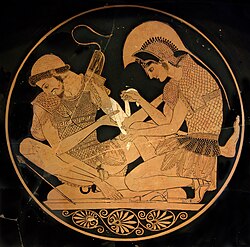

Although there is no explicit sexual relationship between Achilles and Patroclus in the Homeric tradition, a few later Greek authors wrote about what they saw as implied in the text regarding their relationship. Aeschylus and Phaedrus, for example, state there was a clear relationship between them, and they both refer to Achilles as the eromenos of the relationship.[21] Morales and Mariscal state "there is a polemical tradition concerning the nature of the relationship between the two heroes".[21] According to Ledbetter (1993),[22] there is a train of thought that Patroclus could have been a representation of the compassionate side of Achilles, who was known for his rage, mentioned in the first line of Homer's Iliad. Ledbetter connects the way that Achilles and his mother Thetis communicate to the link between Achilles and Patroclus. Ledbetter does so by comparing how Thetis comforts the weeping Achilles in Book 1 of the Iliad to how Achilles comforts Patroclus as he weeps in Book 16. Achilles uses a simile containing a young girl tearfully looking at her mother to complete the comparison. Ledbetter believes this puts Patroclus into a subordinate role to that of Achilles.[22] However, as Patroclus is explicitly stated to be the elder of the two characters,[23] this is not evidence of their ages or social relation to each other.

James Hooker describes the literary reasons for Patroclus' character within the Iliad. He states that another character could have filled the role of confidant for Achilles, and that it was only through Patroclus that we have a worthy reason for Achilles' wrath. Hooker claims that without the death of Patroclus, an event that weighed heavily upon him, Achilles' following act of compliance to fight would have disrupted the balance of the Iliad.[24] Hooker describes the necessity of Patroclus sharing a deep affection with Achilles within the Iliad. According to his theory, this affection allows for the even deeper tragedy that occurs. Hooker argues that the greater the love, the greater the loss. Hooker continues to negate Ledbetter's theory that Patroclus is in some way a surrogate for Achilles; rather, Hooker views Patroclus' character as a counterpart to that of Achilles. Hooker reminds us that it is Patroclus who pushes the Trojans back, which Hooker claims makes Patroclus a hero, as well as foreshadowing what Achilles is to do.[24]

Achilles and Patroclus grew up together after Menoitios gave Patroclus to Achilles' father, Peleus. During this time, Peleus made Patroclus one of Achilles' "henchmen".[25] While Homer's Iliad never explicitly stated that Achilles and Patroclus were lovers, this concept was propounded by some later authors.[26][27][b] Aeschines asserts that there was no need to explicitly state the relationship as a romantic one,[27] for such "is manifest to such of his hearers as are educated men."[28] In later Greek writings, such as Plato's Symposium, the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles is discussed as a model of romantic love.[29] However, Xenophon, in his Symposium, had Socrates argue that it was inaccurate to label their relationship as romantic. Nevertheless, their relationship is said to have inspired Alexander the Great in his own close relationship with his life-long companion Hephaestion.[26][30]

Achilles was younger than Patroclus.[a][c] This reinforces Dowden's explanation of the relationship between an eromenos, a youth in transition, and an erastes, an older male who had recently made the same transition.[33]: 112 Dowden also notes the common occurrence of such relationships as a form of initiation.[33]: 114

Patroclus is a character in William Shakespeare's play Troilus and Cressida. In the play Achilles, who has become lazy, is besotted with Patroclus, and the other characters complain that Achilles and Patroclus are too busy having sex to fight in the war.[34][35]

| Achilles and Patroclus myths as told by story tellers |

|---|

| Bibliography of reconstruction: Homer Iliad, 9.308, 16.2, 11.780, 23.54 (700 BC); Pindar Olympian Odes, IX (476 BC); Aeschylus Myrmidons, F135-36 (495 BC); Euripides Iphigenia in Aulis, (405 BC); Plato Symposium, 179e (388-367 BC); Statius Achilleid, 161, 174, 182 (96 AD) |

Footnotes

- ^ a b Nestor, quoting Patroclus' father Menoetius, reminds Patroclus of his father's advice: "My child, in birth is Achilles nobler than thou, but thou art the elder though in might he is the better far. Yet do thou speak to him well a word of wisdom and give him counsel, and direct him; and he will obey thee to his profit."[31]

- ^ As Martin (2012),[26] argues, "The ancient sources do not report, however, what modern scholars have asserted: that Alexander and his very close friend Hephaestion were lovers. Achilles and his equally close friend Patroclus provided the legendary model for this friendship, but Homer in the Iliad never suggested that they had sex with each other. (That came from later authors.) If Alexander and Hephaestion did have a sexual relationship, it would have been transgressive by majority Greek standards ..."[26]: 99 ff

- ^ Plato in his Symposium[32] has one of his characters say that Achilles was "much the younger, by Homer's account".

References

- ^ a b Martin, Richard (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Carey (1816) Practical English Prosody and Versification, p. 125 fn

- ^ Bechtel (1908) Pronunciation

- ^ "Patroclus". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Patroclus". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020.

- ^ Dares Phrygius, History of the Fall of Troy 13

- ^ Eustathius on Homer, p. 1498; Scholia on Homer, Odyssey 4.343 and 17.134; Hyginus, Fabulae 97

- ^ Tzetzes, John (2015). Allegories of the Iliad. Translated by Goldwyn, Adam; Kokkini, Dimitra. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. pp. 33, Prologue 430, pp. 41, Prologue 525. ISBN 978-0-674-96785-4.

- ^ Scholia on Homer, Iliad 16.14; on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 1.46;

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.13.8 mentions the three possible mothers of Patroclus: (1) Polymele, daughter of Peleus (according to Philocrates), (2) Sthenele, daughter of Acastus and lastly (3) Periopis, daughter of Pheres

- ^ Pythaenetos, quoting the scholiast on Pindar, Olympian Odes 9.107

- ^ Plutarch, Aristides 20.6

- ^ Homer, Iliad 23.85 ff.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 11.785, 16.14.

- ^ Homer. "online text". Iliad. Perseus Digital Library. 23.83–92.

- ^ Finlay, Robert (1980). Patroklos, Achilleus, and Peleus: Fathers and Sons in the Iliad. The Classical World. pp. 267–273.

- ^ a b c d Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Smith, William (1849). Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Boston: Little. p. 140.

- ^ Bulfinch, Thomas (1985). The Golden Age. London: Bracken Books. p. 272.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1911). "Achilles". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- ^ a b Morales, Manuel Sanz; Mariscal, Gabriel Laguna (2003). "The Relationship between Achilles and Patroclus according to Chariton of Aphrodisias". The Classical Quarterly. 53 (1): 292–295. doi:10.1093/cq/53.1.292. JSTOR 3556498.

- ^ a b Ledbetter, Grace (1 December 1993). "Achilles' self-address". American Journal of Philology. 114: 481. doi:10.2307/295421. JSTOR 295421.

- ^ Homer. Iliad. 11.785–790.

- ^ a b Hooker, James (1 January 1989). "Homer, Patroclus, Achilles". Symbolae Osloenses. 64: 30–35. doi:10.1080/00397678908590822.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 474. [full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d Martin, Thomas R. (2012). Alexander the Great: The story of an ancient life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0521148443.

- ^ a b Boswell, John (1980). Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 47.

- ^ Aeschines (1958). The Speeches: Against Telemarchus, on the Embassy, Against Ctesiphon. Translated by Adams, Charles Darwin. London, UK: Harvard University Press. p. 115.

- ^ Plato. Symposium. pp. 179e–180b.

- ^ Lane Fox, Robin (2005). The Classical World. Penguin Books. p. 235.

- ^ Homer. "online text". Iliad. Perseus Digital Library. 11.786.

- ^ Homer. "online text". Iliad. Perseus Digital Library. 180a.

- ^ a b Dowden, Ken (1992). The Uses of Greek Mythology. London, UK: Routledge.

- ^ "Troilus and Cressida Full Text".

- ^ Perkins, Kristin (2019). "Taking the Kissing Path: Making the Homoerotic Modern in Fixing Troilus and Cressida". Borrowers and Lenders. XII (2).

Bibliography

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd., 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato (1925). Symposium. Plato in Twelve Volumes. Vol. 9. Translated by Fowler, Harold N. Cambridge, MA; London, UK: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann Ltd."Online version". Perseus Digital Library.

- Tzetzes, John, Allegories of the Iliad translated by Goldwyn, Adam J. and Kokkini, Dimitra. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, Harvard University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-674-96785-4

Further reading

- Evslin, Bernard (2006). Gods, Demigods and Demons. London, UK: I. Tauris.

- Michelakis, Pantelis (2007). Achilles in Greek Tragedy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. London, UK: Thames and Hudson. pp. 57–61, et passim.

- Sergent, Bernard (1986). Homosexuality in Greek Myth. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Miller, Madeline (2011). The Song of Achilles. London, UK: Bloomsbury.