Polytope

In elementary geometry, a polytope is a geometric object with flat sides, which exists in any general number of dimensions. A polygon is a polytope in two dimensions, a polyhedron in three dimensions, and so on in higher dimensions (such as a polychoron in four dimensions). Some theories further generalize the idea to include such things as unbounded polytopes (apeirotopes and tessellations), and abstract polytopes.

When referring to an n-dimensional generalization, the term n-polytope is used. For example, a polygon is a 2-polytope, a polyhedron is a 3-polytope, and a polychoron is a 4-polytope.

The term was coined by the mathematician Hoppe, writing in German, and was later introduced to English by Alicia Boole Stott, the daughter of logician George Boole.[1]

Different approaches to definition

The term polytope is a broad term that covers a wide class of objects, and different definitions are attested in mathematical literature. Many of these definitions are not equivalent, resulting in different sets of objects being called polytopes. They represent different approaches of generalizing the convex polytopes to include other objects with similar properties and aesthetic beauty.

The original approach broadly followed by Schläfli, Gossett and others begins with the 0-dimensional point as a 0-polytope (vertex). A 1-dimensional 1-polytope (edge) is constructed by bounding a line segment with two 0-polytopes. Then 2-polytopes (polygons) are defined as plane objects whose bounding facets (edges) are 1-polytopes, 3-polytopes (polyhedra) are defined as solids whose facets (faces) are 2-polytopes, and so forth.

A polytope may also be regarded as a tessellation of some given manifold. Convex polytopes are equivalent to tilings of the sphere, while others may be tilings of other elliptic, flat or toroidal surfaces – see elliptic tiling and toroidal polyhedron. Under this definition, plane tilings and space tilings (honeycombs) are considered to be polytopes, and are sometimes classed as apeirotopes because they have infinitely many cells; tilings of hyperbolic spaces are also included under this definition.

An alternative approach defines a polytope as a set of points that admits a simplicial decomposition. In this definition, a polytope is the union of finitely many simplices, with the additional property that, for any two simplices that have a nonempty intersection, their intersection is a vertex, edge, or higher dimensional face of the two. However this definition does not allow star polytopes with interior structures, and so is restricted to certain areas of mathematics.

The theory of abstract polytopes attempts to detach polytopes from the space containing them, considering their purely combinatorial properties. This allows the definition of the term to be extended to include objects for which it is difficult to define clearly a natural underlying space, such as the 11-cell.

Elements

The elements of a polytope are its vertices, edges, faces, cells and so on. The terminology for these is not entirely consistent across different authors. To give just a few examples: Some authors use face to refer to an (n−1)-dimensional element while others use face to denote a 2-face specifically, and others use j-face or k-face to indicate an element of j or k dimensions. Some sources use edge to refer to a ridge, while H. S. M. Coxeter uses cell to denote an (n−1)-dimensional element.

An n-dimensional polytope is bounded by a number of (n−1)-dimensional facets. These facets are themselves polytopes, whose facets are (n−2)-dimensional ridges of the original polytope. Every ridge arises as the intersection of two facets (but the intersection of two facets need not be a ridge). Ridges are once again polytopes whose facets give rise to (n−3)-dimensional boundaries of the original polytope, and so on. These bounding sub-polytopes may be referred to as faces, or specifically j-dimensional faces or j-faces. A 0-dimensional face is called a vertex, and consists of a single point. A 1-dimensional face is called an edge, and consists of a line segment. A 2-dimensional face consists of a polygon, and a 3-dimensional face, sometimes called a cell, consists of a polyhedron.

| Dimension of element |

Element name (in an n-polytope) |

|---|---|

| −1 | Null polytope (necessary in abstract theory) |

| 0 | Vertex |

| 1 | Edge |

| 2 | Face |

| 3 | Cell |

| 4 | Hypercell |

| j | j-face – element of rank j = −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ..., n |

| n − 3 | Peak – (n−3)-face |

| n − 2 | Ridge or subfacet – (n−2)-face |

| n − 1 | Facet – (n−1)-face |

| n | Body – n-face |

Special classes of polytope

Regular polytopes

A polytope may be regular. The regular polytopes are a class of highly symmetrical and aesthetically pleasing polytopes, including the Platonic solids, which have been studied extensively since ancient times.

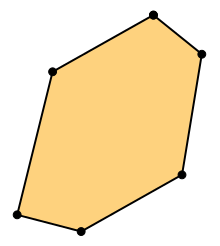

Convex polytopes

A polytope may be convex. The convex polytopes are the simplest kind of polytopes, and form the basis for different generalizations of the concept of polytopes. A convex polytope is sometimes defined as the intersection of a set of half-spaces. This definition allows a polytope to be neither bounded nor finite. Polytopes are defined in this way, e.g., in linear programming. A polytope is bounded if there is a ball of finite radius that contains it. A polytope is said to be pointed if it contains at least one vertex. Every bounded nonempty polytope is pointed. An example of a non-pointed polytope is the set . A polytope is finite if it is defined in terms of a finite number of objects, e.g., as an intersection of a finite number of half-planes.

Star polytopes

A non-convex polytope may be self-intersecting; this class of polytopes include the star polytopes.

Abstract polytopes

An abstract polytope is a partially ordered set of elements or members, which obeys certain rules. It is a purely algebraic structure, and the theory was developed in order to avoid some of the issues which make it difficult to reconcile the various geometric classes within a consistent mathematical framework. A geometric polytope is said to be a realization of some associated abstract polytope.

Self-dual polytopes

In 2 dimensions, all regular polygons (regular 2-polytopes) are self-dual.

In 3 dimensions, the tetrahedron is self-dual, as well as canonical polygonal pyramids and elongated pyramids.

In higher dimensions, every regular n-simplex, with Schlafli symbol {3n}, is self-dual.

In addition, the 24-cell in 4 dimensions, with Schlafli symbol {3,4,3}, is self-dual.

History

The concept of a polytope originally began with polygons and polyhedra, both of which have been known since ancient times:

It was not until the 19th century that higher dimensions were discovered and geometers learned to construct analogues of polygons and polyhedra in them. The first hint of higher dimensions seems to have come in 1827, with Möbius' discovery that two mirror-image solids can be superimposed by rotating one of them through a fourth dimension. By the 1850s, a handful of other mathematicians such as Cayley and Grassman had considered higher dimensions. Ludwig Schläfli was the first of these to consider analogues of polygons and polyhedra in such higher spaces. In 1852 he described the six convex regular 4-polytopes, but his work was not published until 1901, six years after his death. By 1854, Bernhard Riemann's Habilitationsschrift had firmly established the geometry of higher dimensions, and thus the concept of n-dimensional polytopes was made acceptable. Schläfli's polytopes were rediscovered many times in the following decades, even during his lifetime.

In 1882 Hoppe, writing in German, coined the word polytop to refer to this more general concept of polygons and polyhedra. In due course, Alicia Boole Stott introduced polytope into the English language.

In 1895, Thorold Gosset not only rediscovered Schläfli's regular polytopes, but also investigated the ideas of semiregular polytopes and space-filling tessellations in higher dimensions. Polytopes were also studied in non-Euclidean spaces such as hyperbolic space.

During the early part of the 20th century, higher-dimensional spaces became fashionable, and together with the idea of higher polytopes, inspired artists such as Picasso to create the movement known as cubism.

An important milestone was reached in 1948 with H. S. M. Coxeter's book Regular Polytopes, summarizing work to date and adding findings of his own. Branko Grünbaum published his influential work on Convex Polytopes in 1967.

More recently, the concept of a polytope has been further generalized. In 1952 Shephard developed the idea of complex polytopes in complex space, where each real dimension has an imaginary one associated with it. Coxeter went on to publish his book, Regular Complex Polytopes, in 1974. Complex polytopes do not have closed surfaces in the usual way, and are better understood as configurations. This kind of conceptual issue led to the more general idea of incidence complexes and the study of abstract combinatorial properties relating vertices, edges, faces and so on. This in turn led to the theory of abstract polytopes as partially ordered sets, or posets, of such elements. McMullen and Schulte published their book Abstract Regular Polytopes in 2002.

Enumerating the uniform polytopes, convex and nonconvex, in four or more dimensions remains an outstanding problem.

In modern times, polytopes and related concepts have found many important applications in fields as diverse as computer graphics, optimization, search engines, cosmology and numerous other fields.

Uses

In the study of optimization, linear programming studies the maxima and minima of linear functions constricted to the boundary of an n-dimensional polytope.

In linear programming, polytopes occur in the use of Generalized barycentric coordinates and Slack variables.

See also

- List of regular polytopes

- Convex polytope

- Regular polytope

- Semiregular polytope

- Uniform polytope

- Abstract polytope

- Bounding volume-Discrete oriented polytope

- Regular forms

- Intersection of a polyhedron with a line

- Extension of a polyhedron

- Coxeter group

- By dimension:

- 2-polytope or polygon

- 3-polytope or polyhedron

- 4-polytope or polychoron

- 5-polytope

- 6-polytope

- 7-polytope

- 8-polytope

- 9-polytope

- 10-polytope

- Polyform

- Polytope de Montréal

- Schläfli symbol

- Honeycomb (geometry)

References

- ^ A. Boole Stott: Geometrical deduction of semiregular from regular polytopes and space fillings, Verhandelingen of the Koninklijke academy van Wetenschappen width unit Amsterdam, Eerste Sectie 11,1, Amsterdam, 1910

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1973), Regular Polytopes, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-61480-9.

- Grünbaum, Branko (2003), Kaibel, Volker; Klee, Victor; Ziegler, Günter M. (eds.), Convex polytopes (2nd ed.), New York & London: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-00424-6.

- Ziegler, Günter M. (1995), Lectures on Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 152, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Polytope". MathWorld.

- "Math will rock your world" – application of polytopes to a database of articles used to support custom news feeds via the Internet – (Business Week Online)

- Regular and semi-regular convex polytopes a short historical overview: