Rivington

| Rivington | |

|---|---|

Rivington Pike, from Georges Lane | |

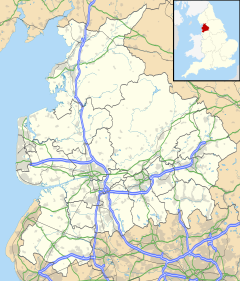

Location within Lancashire | |

| Area | 3.97 sq mi (10.3 km2) |

| Population | 109 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 27/sq mi (10/km2) |

| OS grid reference | SD626144 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BOLTON |

| Postcode district | BL6 |

| Dialling code | 01204 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Rivington is a village and civil parish of the Borough of Chorley, Lancashire, England, occupying 2,538 acres (4.0 sq mi; 10.3 km2). It is about 6 miles (9.7 km) southeast of Chorley and about 8+1⁄2 miles (13.7 km) northwest of Bolton.[1] Rivington is a rural area consisting primarily of agricultural grazing land, moorland, with hill summits including Rivington Pike and Winter Hill within the West Pennine Moors. The area has a thriving tourist industry centred around reservoirs created to serve Liverpool in the Victorian era and Lever Park created as a public park by William Lever at the turn of the 20th century, with two converted barns, a replica of Liverpool Castle and open countryside. Rivington and Blackrod High School is located here. Rivington and its village had a population of 109 at the 2011 Census.[2][3]

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]

The name Rivington is made up of three elements: riv is from the Old English hrēof meaning rough or rugged; ing is a place name forming suffix that seems to have crept in over the years; the last is the Old English tūn meaning a farmstead, estate or settlement.[4][5] Together they indicate a farmstead or settlement at the rough or rugged place. Another suggestion is a place at the rowan trees.[6]

Rivington was recorded in many ways in earlier centuries, Rowinton, Rawinton, and Revington were used in 1202; Ruhwinton in 1212, Riuiton in 1226, Rowynton and Rouynton in 1278, Roynton in 1332, Rouyngton in 1400, Revyngton although rare, from the 14th[7] until the 16th century the area was known as 'Rovington', being the name used on a royal charter in 1566[8][9] along with an alias of 'Ryvington'.[4]

Early history

[edit]A Neolithic or Bronze Age stone, with a cup and ring mark dating from between 2000 and 3000 BC, was found near the Lower Rivington Reservoir in 1999.[10] It is possible that settlements have existed in the area around Rivington since the Bronze Age.[11] Arrowheads, a flint knife, scrapers and the remains of cremations were excavated from a Bronze Age cairn at Noon Hill in 1958 and 1963–64.[12] In 2024 a neolithic axe head was found by a local man next to a footpath.[13] It is possible that the name Coblowe on the eastern bank of the Lower Rivington Reservoir derives from the Old English hlaw, a hill, which denoted an ancient barrow or burial place.[14] Evidence for the existence of a settlement here in Anglo-Saxon times is found in the Rivington and Coblowe names.[15]

Manor

[edit]Although the manor is not registered at the land registry, the manor has a long history with the majority share of seven-eights originally held by the Pilkington family of Lancashire and is recorded as early as 1212[16] This share had reduced to five-eights at the sale of the manor in 1611 to their relations Robert Lever and Thomas Breres. Inheritance of the Pilkington share of the manor is assumed next to have passed by inheritance alongside Rivington hall thereafter. In 1729 John Andrews of Little Lever purchased the Breres' share of Hall and its associated land and his property was inherited by the Cromptons by the nineteenth century. Other owners of the manor were by a quarter originally owned by the Lathoms and an eighth by the Shaws. In 1765 the Shaws and their relations the Roscoes inherited the one-eight share.[17] Leverhulme was the last owner of the 5/8 share, then a local man, now deceased held the 1/8 share transferred from the Cunliffe Shaws and his records are held at Bolton archives. The 1/4 share owner is untraced. United Utilities claims that the Manor is extinguished since 1902.

Landmarks

[edit]

The most prominent of all buildings in Rivington, on the skyline near the summit of Rivington Pike, is the tower, one of 28 listed buildings.[18][19]

Outside the village centre landmarks include Rivington Hall and its adjacent Hall Barn. At Lever Park on the bank of the Lower Rivington Reservoir is a replica of Liverpool Castle, Great House Barn: both barns were repurposed and altered to create tea rooms in the early 20th century. What was Lever Park Information centre at Great House Farm is now used by the Heritage Trust as a gift shop, the lower floors are public toilets and adjacent buildings used as storage.

At George's Lane, the road from Horwich to Rivington Pike, was the Sportsman's Arms, long-since closed, now the Pike Cottage, and adjacent is Pike Snack Shack with its commanding views across the hills and valley, the location featured in Sunday Times Good Walks.[20]

On the hillside the former Bungalow Grounds contain 11 listed structures, being remains of its garden features, although the planting has long since gone or been drastically modified. This area is notable as being designed by TH Mawson. A feature visible on the skyline is the Pigeon Tower, now surrounded by a recent managed woodland, with many steps and paths of crazy paving with some remaining stone summer houses. Its former public toilet is now a cafe.[21][22]

Within the village buildings with listed status are Wilkinson's and a cottage attached to right, Rivington School, Rivington Church and the Unitarian Chapel, the two latter being active places of worship. Fisher House operated as a school in the mid-Victorian period[23] and later as a Temperance Hotel in that era - it is now a secluded private residence.[15][11][24] The village stocks are a feature on Rivington village green, inscribed with "T W 1719" on the stone base.

Near Horrobin Embankment, Horrobin Lane, which passes between the Lower and Upper Rivington reservoirs, is a car park. This was the former site of the Black O'Moors Hotel and Bowling Green Public House, adjacent is Rivington Bowling Club, Bowling Green and Club House, operating as a tea room from 11am.[25][26]

Social history

[edit]Rivington was once an arable farming and grazing agricultural-based area, transformed after 1850 by the Rivington Reservoir Scheme which led to new businesses providing for a large number of workers who arrived for what was a large-scale build. As the Lower Rivington Reservoir was completed the tourist industry was also born and has since been dominant alongside farming. Prior to this Rivington was a rural village built around what is now the village green. Its inhabitants were employed in agriculture on scattered local farms. The textile industry was a secondary form of income until the industrial revolution, alongside farming. Textile bleaching took place on the River Douglas at Knoll Wood which was closed to protect the water catchment of the reservoirs and demolished in 1868 by Liverpool Corporation, some remnants of its dam still remain. The cottage industry of Handloom weaving and use of the Putting-out system was common in the 18th to early 19th century, Samuel Oldknow was a prominent local figure, his family grave being at the Unitarian Chapel. Income was also generated from the quarries, coal mining was on a small scale at Rivington Moor.[15][27] Rivington Moor Colliery employed two workers mining coal for local use.[28]

The house New Hall, opposite the chapel, until its demolition by Liverpool Corporation in 1905, operated a commercial slaughterhouse. The house had a date stone of 1642 and its barn, which survived demolition, built in the early 19th century, has since been converted into a house in 2015.[29][15] New Hall was a dwelling of the Pilkington family for centuries. In 1544[30] reference is made to its adjacent field, Ferneley, possessed by the family from at least 1336.[31][32] The house was sold in 1611 to George Aynesworth.

Water power

[edit]Prior to the reservoirs the valley of Rivington was mostly farmland, with little natural woodland, a small village with stone cottages, and a pub. The valley had a stream flowing through, crossed by packhorse bridges. Lester Mill was located near the upper reservoir and there was a mill utilising water power once located where now stands the village hall. The mill was used as a smithy in the 19th to early 20th century.[33] A further water mill was located at Rivington Hall. In the 19th century, farming was reduced with the construction of reservoirs.[33] The area of the Rivington Unitarian Chapel is named Mill Hill on the 1848 OS map and extended to Croft Bridge, crossing Hall Brook. The Victorian 'School Houses' became known as Mill Hill cottages.[15] Mill Dam wood is at the rear of the Vicarage - a pond existed there prior to the reservoir construction. On the watercourse is a ruin that could be a former water wheel house.[34][35]

A water mill and kiln was mentioned in a deed of 1544 and in a sale agreement of Rivington Hall in 1611. Use of a kiln would have been part of the agricultural milling process. A water mill was once located in a small deep valley at the rear of the hall.[36]

Water catchment

[edit]The Industrial Revolution ended the viability of cottage industries such as weaving, small mines closed and the long-term population decreased as the water authority cleared land in the Rivington Pike Scheme catchment area, that being the name of the plans for the building of the chain of reservoirs to supply Liverpool with clean water.

The flooding of the valley for the reservoirs was at first met with significant opposition, but did boost the local economy. Plans required the demolition of some existing properties and the flooding of farmland. The original proposal was to demolish all buildings in the village, which was stopped by local opposition. Leverhulme, with his political influence, was instrumental in saving the village and seeing protections put in place in the Liverpool Corporation Act 1902. The building of the chain of reservoirs required a large labour force and during and after the build resulted in an unexpected influx of tourists.[15]

In the early 20th century tourism had led to two hotels, busy public houses, tea rooms and many offshoot businesses including a wash house at Rivington Hall, supplied by Leverhulme's father James Lever. The tourist industry was further increased with the opening of Lever Park in 1904.

Reservoirs

[edit]

Rivington was dramatically changed by the construction of the Rivington Reservoir Chain through the contentious 'Rivington Pike Scheme' originally to supply clean drinking water to the city of Liverpool. It now primarily supplies 70,000 households in the Wigan area and can be used to supply Liverpool, Merseyside and Manchester.[37] The original scheme flooded the valley creating what is now the 10,000 acre Rivington watershed.[38] Nine properties in the valley were demolished before construction work began. The scheme was undertaken by Thomas Hawksley between 1850 and 1857. The Liverpool Corporation Act 1902 (2 Edw. 7. c. ccxl) was used to purchase large areas of occupied land and to construct five reservoirs and a water treatment works at the south end of Lower Rivington with a 17-mile (27 km) pipeline to storage reservoirs at Prescot. Water from two higher level reservoirs, Rake Brook and Lower Roddlesworth, was carried south in the Goit, a man-made channel connecting them to the lower reservoirs. In 1942 secret files since released show the reservoirs were used for navigation by German bombers.[39]

Leverhulme era

[edit]In 1900 Liverpool Corporation attempted to acquire the entire area of Rivington and proposed clearing away all of the village which met huge opposition. Properties from mansions to ancient farmhouses were cleared across the catchment area. The clearances were enabled by an act of Parliament, the Liverpool Corporation Act 1902 (2 Edw. 7. c. ccxl). William Hesketh Lever assisted locals in saving the village after he had purchased the hall and lands from the Crompton family and it is assumed rights of the manor. He then later sold the hall and land to Liverpool Corporation by agreement and terms set out in the Liverpool Corporation Act 1902, the transfers completed between 1902 and 1905.[40] The act allowed the corporation to acquire, subject to compensation, properties in the west of the village, including the Black-a-Moors Head public house (known locally as the 'Black Lad') and New Hall, which were demolished between 1902 and 1905. Most farms were cleared. The result was a small settlement that has remained largely unchanged since then.

The Liverpool Corporation Act 1902 makes no mention of the manor but does refer to shooting rights to be retained by Leverhulme – this omission preserved the manor. Leverhulme also retained an interest over all of his former land which is recorded at the Land Registry preventing development.[41] Leverhulme, until his death in 1925, retained a residence on the hillside, shooting rights and use of Rivington Hall as a Museum of Lever Park.[42] The Liverpool Corporation Act 1902 protects Lever Park and at the Terraced Gardens the act only required landowner consent for commercial use.

Little Lake District

[edit]

'The Little Lake District' became the name for the chain of reservoirs created by the Victorian-era Rivington Pike Scheme and had attracted tourists, with increasing visitor numbers. This led to a change in the area's local economy from agricultural to tourism, aided by a new railway at Blackrod in 1841, close to Horwich Vale and a rapid increase in population at Horwich with the arrival of the Horwich Railway Works and railway station, within walking distance. The area attracted well known landscape artists.

The open countryside and moorland had, by the Victorian era, become a public asset the working classes especially wanted to preserve access to and was the site of the Winter Hill mass trespass in 1896.[43]

Lever Park

[edit]

Leverhulme was fond of the area that he got to know well as a boy and a place he and his wife frequently visited whilst courting. He had a keen interest in its history and as such he sponsored and contributed to the book titled 'A Short History of Rivington' published in 1904, in which is the map of the park.[44] [45] Leverhulme also supported open access to the fields and moorland.[46] Leverhulme donated 364 acres (147 ha)[47] of land for the creation of a public park at Rivington in a proposal to Bolton in 1901. The hall became part of Lever Park and the Crompton family had remained resident at the hall until 1910 as part of an agreement of sale, then afterwards it was a museum until Leverhulme's death in 1925. By the early 1950s it was derelict but it was rescued and leased as a residence by the Salmon family.[47]

The park became formally created and protected in law within the Liverpool Corporation Act 1902 (2 Edw. 7. c. ccxl), enshrining in law that the corporation and its successors shall manage Lever Park, named after Leverhulme[48] and keep open the park for the "free and uninterrupted enjoyment of the people of his native town of Bolton".[49][41]

The present owner and successor to the corporation of Liverpool is United Utilities. The main area of the park is adjacent to the Lower Rivington Reservoir and behind Rivington and Blackrod High School toward Rivington Hall Barn. Rivington Pike, although a distance from the reservoirs and now owned by Chorley Council, is part of Lever Park – it is mentioned as such in the Lever Park Act 1969 and protected under the wider 1902 act.[50][45] Access to Lever Park very briefly stopped during the Great War and was met with significant public objection. The park land was formerly farmland belonging to The Crosses, Great House Farm and Rivington Hall.[15][51][47] Leverhulme sold the remaining areas outside the park to Liverpool Corporation in 1905 and retained an interest by a covenant on the land preventing building without his or his heirs' consent, other than by farms and for operation of the water works.[51]

Two pillars commemorating the gift of Leverhulme mark the entry to the area named Lever Park and are located at the junction of Scholes Bank and Lever Park Avenue, Horwich, inscribed with the words "William Hesketh Lever 1st Viscount Leverhulme. Lever Park the gift of William Hesketh Lever 1st Viscount Leverhulme born at 6 Wood Street, Bolton, September 19, 1851 died at Hampstead, London, May 7, 1925. For the benefit of the citizens of his native town and neighbourhood by act of parliament in 1902 the ownership and care of the park were vested in the Corporation of the City of Liverpool". The park opened in 1904 and retains its tree-lined avenues and a network of footpaths. A dedication ceremony took place to dedicate the park to the people of Bolton on 10 October 1911.

The park was at its peak until Leverhulme's death in 1925, after which everything including buildings, Rivington Hall Museum contents, Leverhulme's Bungalow and contents including fine art, furniture, antiques, Rivington Hall Zoo animals and even the ducks and pigeons were sold by auction. The work on the replica castle stopped.[52] The park was a staging post for troops in the Second World War and its barns and adjacent land used to store and produce foods. The park suffered significant neglect in this period, the hall became a derelict building with broken windows. However it was saved and remains an attraction after Salmon Catering agreed a lease.[15]

Today Lever Park consists of avenues of woodland with bridleways and footpaths converging on a replica castle. The routes are former roads which are in disrepair while the main access route for vehicles is Rivington Lane and has limited car parking. There are two converted barns which trade as tea rooms serving food and drinks and Rivington Pike Tower is a landmark on the hill. The valley area gives good vantage points to enjoy the lower Rivington reservoir and the hill is popular with hikers and mountain bike enthusiasts. There are boating facilities at the Anderton Centre and a Go Ape operates adjacent to the Great House Barn with toilets nearby. The area is popular with a variety of user groups including ramblers, cyclists, horse riders, motorcyclists, young and old and families wishing to enjoy the countryside.

Rivington Castle

[edit]Leverhulme commenced the building of a folly in 1911, named Rivington Castle, a scale replica of Liverpool Castle at Coblowe Hillock near the Lower Rivington Reservoir. Grade 2 listed since 1967 it is one of the most important features of Lever Park. The build commenced in 1912 with clearance of the land and digging of foundations, with the first foundation stone laid in 1913,[15] and ended on Leverhulme's death in 1925, after which the one tonne crane, stone bogie and other equipment used for the building project including barrows and the workers' shed were sold by auction and cleared from the site.[52]

Access to the interior had been blocked by steel bars in the post-war decades after World War Two – it is now open to the public. The structure has been altered a number of times by the landowner, before and after listed building status, with the demolition of a stone spiral staircase leading to the 'Great Hall' and stone steps that led to the keep, known as 'The Great Tower', a ledge remains. The castle walls were altered by rebuilding to an angular style at the north wall and near the Keep, stonework was also removed from the wall of the prison tower as it joins the ante-chapel. The work was undertaken in 2012 as part of safety work in an effort to stop visitors climbing.[53][54]

Leverhulme's former gardens

[edit]

At the slope of Rivington Pike is an area of woodland, once a gardens serving a Bungalow once owned by Leverhulme but demolished in 1948. The site has surviving stone structures that formed part of the Italian style gardens, a number of stone summer houses, footpaths, steps, bridges, three ponds, streams and the restored Pigeon Tower. A Japanese style gardens was added in 1923, its features have since been lost but its pulhamite pond remains. Further down the hillside a section was built in 1921 as a man-made ravine.[48][55] From 1939 the site passed to United Utilities and is now leased to Rivington Heritage Trust who use the grounds as an open-air venue.[56]

There is a public footpath and a bridleway from Lever Park to Rivington Pike and Terraced Gardens. The public footpath number 82 runs through the gardens from the Ravine via the former Japanese and Kitchen Gardens, which is also an area of open access land with a right to roam.[57][58]

Governance

[edit]

Rivington was a township in the ecclesiastical parish of Bolton le Moors, in the Salford hundred in Lancashire.[59] It became part of the Chorley Poor Law Union, formed in 1837, and took responsibility for the administration and funding of the Poor Law in that area.[60] The parish had an unusual method of deciding their Mayor until the mid 19th century. The person was selected according to how quickly they got drunk on the eve of the annual event known as 'Club Day' when a day of heavy drinking commenced and villagers dressed in fancy dress, going from house to house banging on doors till the early hours of the morning to collect funds for the 'dignity of the office'.[15] In 1866 Rivington became a civil parish. It was part of the Chorley Rural Sanitary District from 1875 to 1894, and part of Chorley Rural District from 1894 to 1974.[61]

Since 1974 Rivington has been a civil parish of the Borough of Chorley, which comprises 47 councillors each elected for four-year terms to represent wards in the borough. Rivington is part of the Heath Charnock and Rivington ward.[62] Chorley is part of the Lancashire County Council created in 1889 under the Local Government Act 1888 and reconstituted under the Local Government Act 1972. Rivington is part of the Chorley Rural East ward.[63] Rivington has its own parish council.[64]

Rivington is part of the Chorley parliamentary constituency, which elected Lindsay Hoyle as Member of Parliament for the Labour party at the 2010 General Election. He became Speaker of the House of Commons after the 2019 General Election.

Geography

[edit]| Rivington | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rivington is situated on the moorland fringe between the high moorland of the West Pennine Moors and the fields below. The landscape is characterised by marginal pastures with isolated farmsteads, reservoirs and disused mines and quarries scattered across the hillsides. There is an extensive network of footpaths providing public access.[66] The reservoir valleys are dominated by expanses of water and the Victorian gothic architecture of the dams and embankments surrounded by woodland.[67]

To the east of Rivington is Rivington Pike and to the west the flatter land of the Lancashire Plain. Rivington is north of Horwich and Bolton and to the south of Anglezarke Moor and Yarrow Reservoir. To the west of the village is the wide shallow valley containing the Anglezarke, Upper and Lower Rivington reservoirs. The village is accessed from the west by a road on top of the 876-foot (267 m) long Horrobin Embankment, a dam that separates the Upper and Lower Rivington reservoirs.[68] The River Douglas has its source on Winter Hill, and flows in a southwest direction forming part of the southern boundary. The River Yarrow has its source on Anglezarke Moor and forms the northern boundary.[27] The area of the township is 2,768 acres (4.3 sq mi; 11 km2), the reservoirs and filter beds occupy 275 acres (111 ha).[69]

The underlying geology has been sampled by the British Geological Survey, the grit consists of two types of a flag type sandstone with thin coal measures in parts, common here is Millstone Grit. Stone was quarried for local use.[70]

Around Rivington are chalybeate springs and in Dean Wood is a waterfall with a descent of 32 feet (9.8 m).[71]

Demography

[edit]In 2001, 144 people lived in Rivington, 63 males and 81 females.[72] There were 48 households, of which 34 lived in detached houses and 14 in terraced or semi-detached properties. Most households, 60%, were owner-occupied; the remainder were privately rented.[73] The mean age of the population was 53.4 years.[74] In 2001 most of those employed, 47, worked in the service industries. Ten worked in extractive and manufacturing industries, and three males were unemployed. The average distance travelled to work by employed persons was 12.7 miles (20.5 km).[75]

Population change

[edit]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources:[76][2][77][78][79] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]

Rivington is today a thriving tourist area, popular with day trippers and for special events, particularly large gatherings such as weddings. Its park, woodlands, replica castle, tea houses and bars along with historic buildings and structures have remained popular attractions with visitors. United Utilities through its Heritage Trust has tapped into this revenue over the last decade to fund its obligations to maintain its land and property there. The trust hosts events at the site of Leverhulme's former gardens and sells tourist merchandise at the former Lever Park information centre.[15] Agriculture, mainly sheep farming, continues.[15][80] The local schools are significant employers in the area alongside leisure and tourism. Employers include the Hall Barn, GoApe and the Anderton Centre at the Lower Reservoir providing boating and event hosting.[11]

Transport

[edit]Rivington is to the east to the M61 motorway, which connects the M6 and Preston to the north with the M60 and the Greater Manchester conurbation to the south. The nearest access is at Junction 6. The village is accessed by minor roads from Horwich to the south and Adlington to the west. A winding road to the north passes through Anglezarke and a road over the moors to the east leads to Belmont. The nearest places with regular bus services are Horwich to the south and Adlington to the west, which are served by buses between Bolton and Chorley or Preston.

The arrival of the Manchester and Bolton Railway's extension to Preston and opening of Blackrod railway station in 1841 brought visitors to the area. The line remains open with stations at Blackrod and Horwich Parkway giving access to Bolton, Manchester, Chorley and Preston.[81]

Education

[edit]

Rivington Grammar School's charter was granted to Bishop James Pilkington by Queen Elizabeth I in 1566. for the creation of 'The Free School of Queen Elizabeth in Rovington', the school opened in 1575 and was rebuilt in 1714, at the time it was a male only school. Blackrod Grammar School, founded in 1568, merged with it in 1875. In 1882 Rivington & Blackrod Grammar School opened on a site at the south of the township, close to the boundary with Horwich. The school is now Rivington and Blackrod High School, a specialist technology college, focusing on design and technology, mathematics and science. Year Seven pupils occupy the former Horwich County Secondary School.[82]

The old grammar school building in the village centre is now occupied by Rivington Foundation Primary School.[83]

Religion

[edit]

Rivington was a chapelry in the ancient ecclesiastical parish of Bolton le Moors until it became a parish in its own right. Rivington Church was founded in 1566, along with the school. It remains an active Anglican place of worship holding service each Sunday.[84]

The Church is built on the site of an earlier chapel that was named in a deed by Margaret Pilkington and her son Robert in 1476. The chapelry covered Rivington and the surrounding areas of Anglezarke, Hemshaws and Foulds and was recognised in the Royal patent founding Rivington School in 1566. In 1628 a chapel was built "upon a little toft and quillet of land" by the local population and divine service was celebrated "for many years of antiquity".[27]

The early-16th-century chapel was rebuilt in 1666 and altered and restored in 1861.[15] The church is a small plain building built in sandstone with a bell turret. It is an Anglican church and unusual in that it is not dedicated to a saint or martyr, but referred to as Rivington Church.[84]

Rivington Unitarian Chapel is an active place of worship holding regular services on the first and third Sunday of each month in addition to baptisms, weddings and blessings. The chapel was built with a bellcote of local stone in 1703. It was founded as a Presbyterian church and became Unitarian in the late 18th century. The chapel, which retains its box pews, was restored in 1990.[85]

Notable campaigns

[edit]1896 mass trespass

[edit]A mass trespass of 12,000 people occurred in 1896 at Winter Hill on the route from Halliwell toward Rivington Moor in response to the Smithills Hall land owner Colonel Henry Ainsworth, who frequently went shooting game on the moors. He decided to block off public access at Coal Pit Road by installing a gate and placing guards there to block all from passing. This route was well used by workers to and from Bolton. At the time many industries were affected, from coal mines, brick works, bleaching and dying, textile works, agriculture, general labourers and the many people resident at the moorland farms in a wide range of jobs nearby – even travel for picking wimberries in the autumn and for crossing the moor to visit the Pike Fair at Rivington in Easter were blocked from access. By this time fresh air and freedom of open countryside had become a valuable resource as an escape from the industrially polluted towns and poor living and work conditions. Rivington had become a popular day trip destination for all walks of life. The public responded to the gate by breaking it down and scuffles broke out over two days to force Colonel Ainsworth to remove obstructions.[86] The demonstration is commemorated with a stone on Coalpit Road. It was a forerunner of the Kinder Scout mass trespass and an early battleground of the right to roam. Winter Hill was the biggest rights-of-way battle in British history. Over time people were able to use the disputed route without hindrance and in 1996 the road was declared a public right of way.[87][88] The demonstration is commemorated by a memorial stone on Coal Pit Road, below Smithills Moor. In the 20th century many industries closed in the area and depopulation began along with a shift to town-living in consequence of the advance of factory working, therefore use of the route declined. A modern gate was reinstalled across this road after privatisation of the water company.[43][89]

1989 water privatisation

[edit]Lever Park was the gift of Lord Leverhulme to the people of Bolton to enjoy freely. He had been concerned that access to the fields and moorland of Rivington was becoming more restricted. Right of access had been very strongly defended even in times of war.[46] The freedom to roam the countryside came under threat by the Water Bill after water supplies and land forming the catchment area had been moved out of public ownership and were transferred to private corporations in the Water privatisation in England and Wales. This pre-dated legal protections of rights to roam on 'open access land' enshrined in law in the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (CROW). There was a sudden and significant increase in use of gates and fences with stiles on footpaths and bridleways appearing from 1989. In response at Rivington 3,000 local campaigners demonstrated and took a pledge to protect the area from then on after attending a meeting of opponents to the bill, organised as a rally at Rivington, led by the Ramblers Association in association with the Open Spaces Society and attended by Ann Taylor MP; mountaineer Chris Bonington; Ramblers' chairman Chris Hall; the leader of Lancashire County Council, Louise Ellman, and Kinder Scout trespass veteran Benny Rothman,[90][91][92] The water company persisted into the 21st century to attempt to block access to roads in contravention of the Highways Act.[15]

1997 Lever Park Bill

[edit]Lever Park was again under threat in a further attempt by the water company supported by Horwich Town Council who attempted to remove statutory protection through an act of Parliament in 1997.[93] Employees of the water company had formed the Rivington Heritage Trust as a front for the by-then privately owned water company to obtain charitable funding through what was known as the Blue Planet Scheme, which involved moving ownership of the land to the trust and monetarising it, whilst removing the expense of maintaining the park from the water company, despite a statutory duty imposed by the Liverpool Corporation Act 1902. The plan was met with considerable local opposition – a 5,807 signature petition was presented in opposition with grave concerns about the Lever Park Bill.[93] The act of Parliament was blocked by a cross party group of six regional Conservative and Labour MPs Terry Lewis, Tom Sackville, Peter Thurnham, Andrew Bennett and Gerald Kaufman and was opposed by the local MP, Den Dover.[94][95][96]

Rights of way

[edit]Lever Park is protected under statutory powers within the Liverpool Corporation Act 1902 ensuring "free and uninterrupted enjoyment". The area is popular with walkers, cyclists and horse riders with footpaths, bridleways and roads providing access to the park, hillside and surrounding moorland.[97] Rivington moor, Winter Hill, Rivington Pike, Brown Hill and the former Japanese and Kitchen Gardens within the Bungalow Grounds are part of an extensive area of open access land recorded at Lancashire County Council and has a right to roam protected by the statutory powers in the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000.[98][99]

There is a network of roads that provide access to Rivington recorded on the National Street Gazetteer. Access to Lever Park by vehicle is via Rivington Lane, (USRN 7401372). Many former roads in Lever Park are gated and are now bridleways along with a network of public footpaths. Toward Rivington Pike the old coach road is Belmont Road (USRN 7400767) and is an open public road from Horwich, the road becomes rougher and less maintained the further up the hill it climbs in the direction of the Pigeon Tower, where it splits. The descending road there leads to Lower House car park. It is legally used for 'Green Laning', the road's surface is washed away and not maintained, the route leading to Rivington Rd and the moorland is gated.[100][101][99]

Covid

[edit]The public was prevented from access to Lever Park, in conflict with the rights afforded by law enshrined in the Liverpool Corporation Act 1902 of "free and uninterrupted enjoyment" and the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 during Easter by the landowner's agent, Rivington Heritage Trust alongside police for first time in its history in 2020 and 2021 during the Covid pandemic.[102] In June 2020[103] Police stepped up patrols on rumours of a gathering, also in May 2021 police, United Utilities/Rivington Heritage Trust and North West 4×4 Response went patrolling with a view to arrests for offences of "gathering and proceeding to a gathering under the Criminal Justice and Public order act".[104] In June 2021 police officers are reported to have 'swooped' on Rivington to prevent a rumoured gathering.[105]

Sport

[edit]The Rivington Pike Fell Race has been held on Easter Saturday since 1892. The fell race originally started from the Horwich railway works, but since 1930 from the park entrance at Lever Park Avenue. It attracts around 400 runners. The course is 3+1⁄4 miles (5.2 km) long and has a 700-foot (213 m) ascent.[106]

The area around Rivington and Anglezarke was the location for the 2002 Commonwealth Games mountain biking competition.[107] The area is well used by hikers and hillwalkers.

Groups of four wheel drive vehicle owners use a section of Belmont Road for Off-roading. The road is an open public road and is also used by walkers toward the Pigeon Tower from Lower House. The off-roaders' activity has been very controversial due to damage to the road surfaces and adjacent land over many years.[108]

Culture

[edit]Phoebe Hesketh lived at Fisher House in the village where she wrote several volumes of poetry and two partly autobiographical books Rivington: the story of a village and Rivington: village of the mountain ash. She also wrote a biography, My Aunt Edith, about Edith Rigby the suffragette.[109][110]

The artist Alfred East stayed at Roynton Cottage in summer 1909. Lever commissioned a series of paintings of the surrounding landscape, the reservoirs, country park, village and the pike.[111] Lever gave 15 of them to Bolton Art Gallery[112] and others to Bolton School, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool and the Lady Lever Art Gallery[113] at Port Sunlight. East gave two water colours, A glimpse of Rivington Water and In Rivington Park to Kettering Museum and Art Gallery in 1913. The gallery acquired an oil painting in the 1960s entitled From Rivington Pike, the work was an exhibit of the Royal Academy in 1913.[111]

The Bolton Museum and Masonic Lodge, Ridgmont House, Horwich hold a painting titled "Rivington Lakes" dated 1872 and with a variation titled Rivington Valley (1857) held at Walker Art Gallery, by Frederick William Hulme.[114]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Rivington Township Boundaries. GenUKI. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ a b UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Rivington Parish (E04005157)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "West Pennine Moors Management Plan 2010-2020" (PDF). Blackburn Council. Blackburn and Darwen District Council. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ a b Billington 1982, pp. 68–69.

- ^ "Rivington". Key to English Place-Names. the University of Nottingham. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Smith 1989, p. 4.

- ^ Archives. "Debtor: William, the son of William de Radcliffe, Robert de Pilkington of Rivington..." National Archives. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ Irvine 1904, p. 53.

- ^ Kay 1966, p. 156

- ^ "History of Anderton Centre". Anderton Centre. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ a b c "Rivington Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals" (PDF). Chorley Council. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Historic England. "Noon Hill (43486)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ Harrison, Zach (30 June 2024). "Horwich: Neolithic axe head found in eroded footpath". Bolton News. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Irvine 1904, p. xv.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lacey, Paul. "Rivington, Lancashire". Rivington. Angelfire. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Pilkington 1912, pp. 29.

- ^ Shaw 1940, pp. 133–134.

- ^ "Listed Buildings in Rivington, Chorley, Lancashire". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Chorley Borough Council Listed Buildings. Chorley Council. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Finney, Lewis (25 November 2022). "Bolton: Pike Snack Shack mentioned in the Sunday Times Good Walks". Newsquest. Bolton News. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "Listed buildings". Chorley Council. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "List of listed buildings" (PDF). Chorley Council. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Fisher House School" (PDF). Rivington Chapel. Rivington Unitarian Chapel. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Map of Conservation Area" (PDF). Chorley Council. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Rivington Bowling Club". Rivington Bowling Club. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ Hampson 1893, p. 130.

- ^ a b c Farrer & Brownbill 1911, pp. 286–294.

- ^ North and East Lancashire's Mining Industry in 1896. projects.exeter.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Gilkes, Peter E. "Planning Applications" (PDF). Chorley Council. Planning Dept, Chorley. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ Pilkington 1912, pp. 115.

- ^ Pilkington 1912, pp. 255–256.

- ^ Pilkington 1912, pp. 213.

- ^ a b Owen, David (2019). Rivington and District, A History of Rivington Church (Reprint ed.). Rivington: Rivington Chapel Trust. p. 30.

- ^ Rivington Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals (PDF). Chorley Council. 2009. p. 19. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. Lancashire LXXXVI (includes: Blackrod; Bolton; Horwich.) Surveyed: 1845 to 1847 (Map). National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "National Farm Building Types". Historic England. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ "Drought order for Rivington reservoirs withdrawn". 4 August 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "Story of our 'little Lake District'". Lancashire Telegraph. 30 July 2002. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Lacey, Paul (11 July 2019). "Bombers Over Rivington 1942". Internet Archive. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "Liverpool Corporation Act, 1902" (PDF). Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI). Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Liverpool Corporation Act 1902". Legislation Gov UK. Gov UK. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Liverpool Corporation Act, 1902" (PDF). Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI). Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Winter Mass Trespass 1896" (PDF). Rossendale Ramblers. Ramblers Association - Rossendale branch. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Irvine 1904, p. IX.

- ^ a b Irvine 1904, p. vii.

- ^ a b Irvine 1904, p. xiv.

- ^ a b c Pilkington 1912, p. 189.

- ^ a b Smith 1984, p. 22.

- ^ "1902 LIVERPOOL CORPORATION ACT". Rivington Parish Council. RPC. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "1904 Bye-laws amended 1914, 1969 and 1974, Lever Park Rivington, Bye Laws" (PDF). Rivington Unitarian Chapel. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Gov UK". Gov UK. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ a b Leverhulme Collection. London: London : Knight Frank & Rutley. November 1925. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Lever Park, Rivington. Parks and Gardens UK. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Haworth, Glynn (23 July 2012). "United Utilities WPM AMC Report" (PDF). General Update for year 2011 to 2012. United Utilities. Lancashire Country Council SCaMP. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Waymark 2009, pp. 77–81.

- ^ "Charity Overview". Charity Commission. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ "MAGIC Defra Mapping". DEFRA. GOV.UK. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ "Public rights of way map". LCC. Lancashire County Council. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Rivington. GenUKI. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ Workhouse. Workhouses.org. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Relationships / unit history of Rivington. Vision of Britain. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Chorley Council, Democracy. Chorley Council. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ County Councillors by Local Community. Lancashire County Council. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ "Rivington Parish Council". RIVINGTON PARISH COUNCIL. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Rivington Weather, United Kingdom Weather Averages. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ Moorland Fringe. Lancashire County Council. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Reservoir Valleys. Lancashire County Council. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Rivington Reservoirs (main scheme). Engineering Timelines. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Smith 1984, p. 40.

- ^ D. Price, W. B. Wright, R. C. B. Jones, L. H. Tonks, and T. H. Whitehead. "Geology of the country around Preston (One-inch geological sheet 75 New Series)". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lewis, Samuel (1848). "Rivington or Rovington". A Topographical Dictionary of England. British History Online. pp. 676–679. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ "Rivington CP (Parish)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Parish Profile - Accommodation and Tenure". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Parish Profile - People. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Parish Profile - Work and Qualifications". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Area: Rivington (Parish): Key Figures for 2001 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Tatton, Pauline. Local population statistics 1801–1986, Bolton Central Library Archives, Le Mans Crescent, Bolton.

- ^ Rivington SubD Population. A vision of Britain through time. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Rivington CP/Ch. Population. A vision of Britain through time. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Rawlinson 1969, p. 93.

- ^ Horwich Parkway (HWI). National Rail. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ Welcome to Rivington & Blackrod High School. Rivington and Blackrod High School. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ Rivington Foundation Primary School. LancashireCounty Council. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Sunday Service". Rivington Church. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Unitarian Chapel Rivington". Unitarian Chapel Rivington. Rivington Unitarian Chapel. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "The Winter Hill Trespass 1896". Lancashire Past. 3 December 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Salveson, Paul (29 October 2021). "Winter Hill – Britain's biggest 'mass trespass'". Chartist. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Anson, John (13 September 2020). "Winter Hill was the battleground for the right to roam". Bolton News. NewsQuest. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Salveson, Paul (27 August 1982). "Bolton Moors "Liberated" 1896". Tribune.

- ^ Ashbrook, Kate (7 May 2019). "The Rivington Pledge". campaignerkate. General secretary of the Open Spaces Society. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "Richard Harland, 1920 – 2013". Open Spaces Society. 23 February 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Ashbrook, Kate (7 May 2019). "The Rivington Pledge". campaignerkate. General Secretary, Open Spaces Society. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ a b "9.58 pm Mr. Thurnham". Hansard. Parliament UK. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ "Lever Park garden plans scrapped". Bolton News. Associated Press. 17 November 1997. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "Rockers Bill stalled again". Associated Press. Bolton News. 30 January 1997. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "MP vows to Lever Park Bill". Bolton News. 30 January 1997. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Moorland Fringe, Lancashire County Council, archived from the original on 30 October 2010, retrieved 3 May 2011

- ^ "Public Access Land to the North of Bolton". Bolton Council. Bolton Council Highways Dept. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Definitive map". Lancashire GOV UK. Lancashire County Council. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ "National Street Gazetteer". Find My Street. findmystreet.co.uk. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Types of paths in England and Wales". Ramblers Association. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ "Covid: Police break up illegal gathering at Rivington beauty spot". Bolton News. NewsQuest. 6 April 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Quayle, Ewan (20 June 2020). "Police step up patrols after illegal rave rumours in Rivington and Belmont". Newsquest. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Nadeem, Alima (29 May 2021). "Police step up patrols in Rivington after illegal rave plans leak". Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Vesty, Helena (22 June 2021). "'Illegal rave' at beauty spot foiled as police officers swoop on historic Rivington site". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Cornthwaite grabs success at Rivington Pike Fell Race. Lancashire Telegraph. 13 April 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ 2002 Commonwealth Games. TheCGF. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Calderbank, Matthew (26 July 2021). "Police take action against 4x4 drivers who became stuck whilst illegally off-roading on Rivington Moor". Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Harvey, Anne (28 February 2016). "Phoebe Hesketh". Independent. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Brownjohn, Alan (3 March 2005). "Phoebe Hesketh". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ a b Sir Alfred East (1844- 1913). Friends of Kettering Museum and Art Gallery. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ View from the Bungalow, Rivington. ArtUK. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Rivington Water. ArtUK. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Frederick William Hulme. ArtUK. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Billington, W. D. (1982), From Affetside to Yarrow, Ross Anderson Publications, ISBN 0-86360-003-4

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, J., eds. (1911), "Rivington", A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 5, British History Online

- Kay, Margaret M. (1966). The History of Rivington and Blackrod Grammar School (2nd ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Hampson, Thomas (1893), History of Rivington: With Lists of the Clergy and Church Wardens, the Church Wardens Accounts, Particulars of the Rivington and Blackrod Grammar

- Irvine, William Fergusson (1904), A short history of the township of Rivington, Edinburgh: Ballantyne Press

- Lane, Dave (2008), Winter Hill Scrapbook, Lulu, ISBN 978-1-4092-2068-8

- Pilkington, James (1912), The History of the Pilkington family and its branches, from 1066 to 1600 (Third ed.), Liverpool: C. Tinley & Co. Ltd

- Shaw, Ronald Cunliffe (1940), The Records of a Lancashire Family from the XIIth to the XXth Century [On the Shaw family. With plates and genealogical tables.], Preston: Guardian Press

- Rawlinson, John (1969), About Rivington, Nelson

- Smith, M. D. (1984), Leverhulme's Rivington: the story of the Rivington 'Bungalow', Chorley: Nelson Brothers Printers, ISBN 0-9508772-1-2

- Smith, M. D. (1989), Rivington, Lancashire, Nelson Brothers Printers Limited, ISBN 0-9508772-8-X

- Waymark, Janet (2009), Thomas Mawson: Life, Gardens and Landscapes, Frances Lincoln, ISBN 978-0-7112-2595-4

- Mawson, Thomas (1912), The art & craft of garden making (Third ed.), London: B.T Batsford

Further reading

- Hesketh, Phoebe (1972), Rivington: the story of a village, London: Peter Davies, ISBN 0-432-06681-0

External links

[edit]- Rivington photographs

- Chorley Council, Rivington

- Rivington Lantern Images at LCC

- RowMaps, Barry Cornelius - Map of Rivington Bridleways and Footpaths

- Rivington