Spinning (textiles)

Spinning is an ancient textile art in which plant, animal or synthetic fibers are twisted together to form yarn. For thousands of years, fiber was spun by hand using simple tools, the spindle and distaff. Only in the High Middle Ages did the spinning wheel increase the output of individual spinners, and mass-production only arose in the 18th century with the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. Hand-spinning remains a popular handicraft.

Characteristics of spun yarn vary according to the material used, fiber length and alignment, quantity of fiber used, and degree of twist.

History

Hand spinning

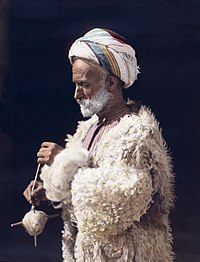

The origins of spinning fiber to make string or yarn are lost in time, but archaeological evidence in the form of representation of string skirts has been dated to the Upper Paleolithic era, some 20,000 years ago.[1] In the most primitive type of spinning, tufts of animal hair or plant fiber are rolled down the thigh with the hand, and additional tufts are added as needed until the desired length of spun fiber is achieved. Later, the fiber is fastened to a stone which is twirled round until the yarn is sufficiently twisted, whereupon it is wound upon the stone and the process repeated over and over.

The next method of twisting yarn is with the spindle, a straight stick eight to twelve inches long on which the thread is wound after twisting. At first the stick had a cleft or split in the top in which the thread was fixed. Later, a hook of bone was added to the upper end. The bunch of wool or plant fibers is held in the left hand. With the right hand the fibers are drawn out several inches and the end fastened securely in the slit or hook on the top of the spindle. A whirling motion is given to the spindle on the thigh or any convenient part of the body. The spindle is then dropped, twisting the yarn, which is wound on to the upper part of the spindle. Another bunch of fibers is drawn out, the spindle is given another twirl, the yarn is wound on the spindle, and so on.[2]

The distaff was used for holding the bunch of wool, flax, or other fibers. It was a short stick on one end of which was loosely wound the raw material. The other end of the distaff was held in the hand, under the arm or thrust in the girdle of the spinner. When held thus, one hand was left free for drawing out the fibers.[2]

A spindle containing a quantity of yarn rotates more easily, steadily, and continues longer than an empty one; hence, the next improvement was the addition of a weight called a spindle whorl at the bottom of the spindle. These whorls are discs of wood, stone, clay, or metal with a hole in the center for the spindle, which keep the spindle steady and promote its rotation. Spindle whorls appeared in the Neolithic era.[2][3]

In mediæval times, poor families had such a need for homespun yarn to make their own cloth and clothes, that practically all girls and unmarried women would keep busy spinning, and spinster became synonymous with an unmarried woman. Subsequent improvements with spinning wheels and then mechanical methods made hand-spinning increasingly uneconomic, but as late as the twentieth century hand-spinning remained widespread in poor countries: in conscious rejection of international industrialization, Gandhi was a notable practitioner.

Industrial spinning

Modern powered spinning, originally done by water or steam power but now done by electricity, is vastly faster than hand-spinning.

The spinning jenny, a multi-spool spinning wheel invented c. 1764 by James Hargreaves, dramatically reduced the amount of work needed to produce yarn of high consistency, with a single worker able to work eight or more spools at once. At roughly the same time, Richard Arkwright and a team of craftsmen developed the spinning frame, which produced a stronger thread than the spinning jenny. Too large to be operated by hand, a spinning frame powered by a waterwheel became the water frame.

In 1779, Samuel Crompton combined elements of the spinning jenny and water frame to create the spinning mule. This produced a stronger thread, and was suitable for mechanisation on a grand scale. A later development, from 1828/29, was Ring spinning.

In the 20th century, new techniques including Open End spinning or rotor spinning were invented to produce yarns at rates in excess of 40 meters per second.

Characteristics of spun yarns

Materials

Yarn can be, and is, spun from a wide variety of materials, including natural fibers such as animal, plant, and mineral fibers, and synthetic fibers. It was probably first made from plant fibers, but animal fibers soon followed.

Twist and ply

The direction in which the yarn is spun is called twist. Yarns are characterized as S-twist or Z-twist according to the direction of spinning (see diagram). Tightness of twist is measured in TPI (twists per inch or turns per inch).[4]

Two or more spun yarns may be twisted together or plied to form a thicker yarn. Generally, handspun single plies are spun with a Z-twist, and plying is done with an S-twist.[5]

Plying methods

Yarns can be made of two, three, four, or more plies, or may be used as singles without plying. Two-ply yarn can also be plied from both ends of one long strand of singles using Andean plying, in which the single is first wound around one hand in a specific manner that allows unwinding both ends at once without tangling. Navajo plying is another method of producing a three-ply yarn, in which one strand of singles is looped around itself in a manner similar to crochet and the resulting three parallel strands twisted together. This method is often used to keep colors together on singles dyed in sequential colors. Cabled yarns are usually four-ply yarns made by plying two strands of two-ply yarn together in the direction opposite to the plying direction for the two-ply yarns.

Contemporary hand spinning

Hand-spinning is still an important skill in many traditional societies. Hobby or small scale artisan spinners spin their own yarn to control specific yarn qualities and produce yarn that is not widely available commercially. Sometimes these yarns are made available to non-spinners online and in local yarn stores. Handspinners also may spin for self-sufficiency, a sense of accomplishment, or a sense of connection to history and the land. In addition, they may take up spinning for its meditative qualities.[6]

Within the recent past, many new spinners have joined into this ancient process, innovating the craft and creating new techniques. From using new dyeing methods before spinning, to mixing in novelty elements (Christmas Garland, eccentric beads, money, etc.) that would not normally be found in traditional yarns, to creating and employing new techniques like coiling,[7] this craft is constantly evolving and shifting.

To make various yarns, besides adding novelty elements, spinners can vary all the same things as in a machined yarn, i.e., the fiber, the preparation, the color, the spinning technique, the direction of the twist, etc. A common misconception is yarn spun from rolags may not be as strong, but the strength of a yarn is actually based on the length of hair fiber and the degree of twist. When working with shorter hairs, such as llama or angora rabbit, the spinner may choose to integrate longer fibers, such as mohair, to prevent yarn breakage. Yarns made of shorter fibers are also given more twist than yarns of longer fibers, and are generally spun with the short draw technique.

The fiber can be dyed at any time, but is often dyed before carding or after the yarn has been spun.

Wool may be spun before or after washing, although excessive amounts of lanolin may make spinning difficult, especially when using a drop-spindle. Careless washing may cause felting. When done prior to spinning, this often leads to unusable wool fiber. In washing wool the key thing to avoid is too much agitation and fast temperature changes from hot to cold. Generally, washing is done lock by lock in warm water with dish-soap.

Techniques

A tightly spun wool yarn made from fiber with a long staple length in it is called worsted. It is hand spun from combed top, and the fibers all lie in the same direction as the yarn. A woolen yarn, in contrast, is hand spun from a rolag or other carded fiber (roving, batts), where the fibers are not as strictly aligned to the yarn created. The woolen yarn, thus, captures much more air, and makes for a softer and generally bulkier yarn. There are two main techniques to create these different yarns: short draw creates worsted yarns, and long draw creates woolen yarns. Often a spinner will spin using a combination of both techniques and thus make a semi-worsted yarn.[8]

Short draw spinning is used to create worsted yarns. It is spun from combed roving, sliver or wool top. The spinner keeps his/her hands very close to each other. The fibers are held, fanned out, in one hand, and the other hand pulls a small number from the mass. The twist is kept between the second hand and the wheel. There is never any twist between the two hands.

Long draw is spun from a carded rolag. The rolag is spun without much stretching of the fibers from the cylindrical configuration. This is done by allowing twist into a short section of the rolag, and then pulling back, without letting the rolag change position in one's hands, until the yarn is the desired thickness. The twist will concentrate in the thinnest part of the roving; thus, when the yarn is pulled, the thicker sections with less twist will tend to thin out. Once the yarn is the desired thickness, enough twist is added to make the yarn strong. Then the yarn is wound onto the bobbin, and the process starts again.

Spinning in the grease

Handspinners are split, when spinning wool, as to whether it is better to spin it 'in the grease' (with lanolin still in) or after it has been washed. More traditional spinners are more willing to spin in the grease, as it is less work to wash the wool after it is in yarn form. Spinners who spin very fine yarn may also prefer to spin in the grease as it can allow them to spin finer yarns with more ease. Spinning in the grease covers the spinner's hands in lanolin and, thus, softens the spinner's hands.

Spinning in the grease only works really well if the fleece is newly sheared. After several months, the lanolin becomes sticky, which makes it harder to spin using the short draw technique, and almost impossible to spin using the long draw technique. In general, spinners using the long draw technique do not spin in the grease.

Spinners who do not spin in the grease generally buy their fibers pre-washed and carded, in the form of roving, sliver, or batts. This means less work for the spinner, as they do not have to wash the lanolin out. It also means that one can spin predyed fiber, or blends of fibers, which are very hard to create when the wool is still in the grease. As machine carders cannot card wool in the grease, pre-carded yarn generally is not spun in the grease. Some spinners, however, use spray-on lanolin-like products to get the same feel of spinning in the grease with this carded fiber.

See also

- Cotton mill

- Crochet

- Knitting

- Loom

- Ontario Handweavers & Spinners

- Spinning wheel

- Weaving

- Magnetic ring spinning

Notes

- ^ Barber, Women's Work, 42–45.

- ^ a b c Watson, Textiles and Clothing, pp. 3–14

- ^ Barber, Women's Work, 37.

- ^ Kadolph, Sara J., ed.: Textiles, 10th edition, Pearson/Prentice-Hall, 2007, ISBN 0-13-118769-4, p. 197

- ^ Plying Yarn with a Spinning Wheel, The Joy of Handspinning

- ^ NYtimes.com

- ^ Toil, Toil, Coils and Bubbles, Knitty Magazine

- ^ Woolen, Semi-Woolen, Semi-Worsted, Worsted Spinning

References

- This article contains text from the 1907 edition of Textiles and Clothing by Kate Heinz Watson, a document now in the public domain.

- Amos, Alden (2001). The Alden Amos Big Book of Handspinning, Loveland, Colorado: Interweave Press. ISBN 1883010888

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1995). Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times, W. W. Norton & Company, new edition, 1995.

- Boeger, Alexis (2005). Handspun Revolution, Pluckyfluff. ISBN 0976725207

- Jenkins, David, editor (2003). The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521341078

- Piponnier, Françoise, and Perrine Mane (1997). Dress in the Middle Ages; Yale UP; ISBN 0300069065

- Ross, Mabel (1987). Essentials of Handspinning, Robin and Russ Handweavers. ISBN 0950729205

- Simmons, Paula (2009). Spinning for Softness and Speed, Chilliwack: British Columbia www.bookman.ca. ISBN 0914842870

- Watson, Kate Heinz (1907). Textiles and Clothing, Chicago: American School of Home Economics (online at Textiles and Clothing by Kate Heintz Watson).

External links

General

- Spinning Guilds Directory – An international list of spinning guilds

- Yarn Museum – Online gallery promoting handspun yarn.

- Yarn and Sewing Threads at Curlie

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Instructional sites

- Joy of Hand Spinning – video instruction