The Outlaw Josey Wales

| The Outlaw Josey Wales | |

|---|---|

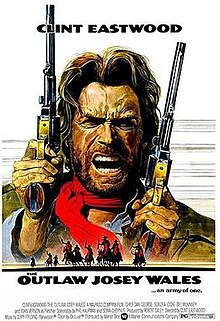

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Clint Eastwood |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Gone to Texas by Forrest Carter |

| Produced by | Robert Daley |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Bruce Surtees |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Jerry Fielding |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.7 million[1] |

| Box office | $31.8 million[2] |

The Outlaw Josey Wales is a 1976 American Revisionist Western film set during and after the American Civil War.[3] It was directed by and starred Clint Eastwood (as Josey Wales), with Chief Dan George, Sondra Locke, Sam Bottoms, and Geraldine Keams.[4][5] The film tells the story of Josey Wales, a Missouri farmer whose family is murdered by Union militants during the Civil War. Driven to revenge, Wales joins a Confederate guerrilla band and makes a name for himself as a feared gunfighter. After the war, all the fighters in Wales' group except for him surrender to Union officers, but they end up being massacred. Wales becomes an outlaw and is pursued by bounty hunters and Union soldiers as he tries to make a new life for himself.

The film was adapted by Sonia Chernus and Philip Kaufman from author Asa Earl "Forrest" Carter's 1972 novel The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales (republished, as shown in the movie's opening credits, as Gone to Texas).[6] The film was a commercial success, earning $31.8 million against a $3.7 million budget. In 1996, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry of the Library of Congress for being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Josey Wales was portrayed by Michael Parks in the film's 1986 sequel, The Return of Josey Wales.[7] His wife Laura Lee was played by Mary Ann Averett in the sequel.

Plot

Josey Wales, a Missouri farmer, is driven to revenge by the murder of his wife and young son by a band of Redlegs, a unit of pro-Union Jayhawker militants from Senator James H. Lane's Kansas Brigade, led by the brutal Captain Terrill.

After grieving and burying his wife and son, Wales practices shooting a gun before joining a group of pro-Confederate Missouri bushwhackers led by William T. Anderson, taking part in attacks on Union sympathizers and army units. At the conclusion of the war, Josey's friend and superior, Captain Fletcher, persuades the guerrillas to surrender, having been promised by Senator Lane that they will be granted amnesty if they hand over their weapons. Wales refuses to surrender, and as a result, he and a young guerrilla named Jamie are the only survivors when Terrill's Redlegs massacre the surrendering men. Wales intervenes and wipes out many of the Redlegs with a Gatling gun before fleeing with Jamie, who dies from a bullet wound after helping Josey kill two pursuing bounty hunters.

Lane forces a reluctant Fletcher to assist Terrill in finding his friend and puts a $5,000 bounty on his head, attracting the attention of Union soldiers and bounty hunters who seek to hunt him down. Along the way, and despite his aversion to traveling with company, Wales accumulates a diverse group of companions. They include an old Cherokee man named Lone Watie; Little Moonlight, a young Navajo woman; Sarah Turner, an elderly woman from Kansas; and her granddaughter Laura Lee, whom Wales and Little Moonlight rescue from a group of marauding Comancheros. Josey and Laura later sleep together as do Lone Watie and Little Moonlight. At the town of Santo Rio, two men, Travis and Chato, who had worked for Sarah Turner's deceased son Tom, join the group.

Wales and his companions find the abandoned ranch once owned by Tom and settle in. Travis and Chato are soon after captured by the feared Comanche tribal leader, Ten Bears. Wales rides to Ten Bears' camp, parleys with him, and makes peace, with Ten Bears taking a blood oath to live in peace with him and his. Wales rescues Travis and Chato and brings them back to the ranch.

Meanwhile, a bounty hunter whose partner was gunned down by Wales at Santo Rio guides Captain Terrill and his men to the town. The following morning, the Redlegs launch a surprise attack on the ranch. Wales's companions open fire from the fortified ranch house, gunning down all of Terrill's men. A wounded Wales, despite being out of ammunition, pursues the fleeing Terrill back to Santa Rio. When he corners him, Wales dry fires his four pistols through all the empty chambers before holstering them. As Terrill draws his cavalry sabre, Wales grabs his hand and, after a slow struggle, forces the blade through Terrill's chest, finally avenging his family.

Returning to the Santa Rio saloon, Wales enters to find the locals are telling Fletcher, along with two Texas Rangers, how an outlaw named Josey Wales had recently been killed in Monterrey, by five pistoleros. The Rangers accept the story, along with a signed affidavit, and move on, while Fletcher says nothing about Wales and pretends not to recognize him. After the Rangers ride off, Fletcher says that he will go to Mexico to look for Wales himself and try to tell him that the war is over. Wales says, "I reckon so. I guess we all died a little in that damned war", before riding off.

Cast

- Clint Eastwood as Josey Wales

- Chief Dan George as Lone Watie

- Sondra Locke as Laura Lee

- Bill McKinney as Terrill

- John Vernon as Fletcher

- Paula Trueman as Grandma Sarah

- Sam Bottoms as Jamie

- Geraldine Keams as Little Moonlight

- Woodrow Parfrey as Carpetbagger

- Joyce Jameson as Rose

- Sheb Wooley as Travis Cobb

- Royal Dano as Ten Spot

- Matt Clark as Kelly

- John Verros as Chato

- Will Sampson as Ten Bears

- William O'Connell as Sim Carstairs

- John Quade as Comanchero Leader

- Frank Schofield as Senator James H. Lane

- Buck Kartalian as Shopkeeper

- Len Lesser as Abe

- Doug McGrath as Lige

- John Russell as "Bloody Bill" Anderson

- Charles Tyner as Zukie Limmer

- Bruce M. Fischer as Yoke

- John Mitchum as Al

- John Chandler as First Bounty Hunter

- Tom Roy Lowe as Second Bounty Hunter

- Clay Tanner as First Texas Ranger

- Bob Hoy as Second Texas Ranger

Production

The Outlaw Josey Wales was inspired by a 1972 novel by supposedly-Cherokee writer Forrest Carter, alias of former KKK Leader and segregationist speech writer of George Wallace, Asa Earl Carter, an identity that would be exposed in part due to the success of the film,[8] and was originally titled The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales and later retitled Gone to Texas. The script was worked on by Sonia Chernus and producer Robert Daley at Malpaso, and Eastwood himself paid some of the money to obtain the screen rights.[9] Michael Cimino and Philip Kaufman later oversaw the writing of the script, aiding Chernus. Kaufman wanted the film to stay as close to the novel as possible in style and retained many of the mannerisms in Wales's character which Eastwood would display on screen, such as his distinctive lingo with words like "reckon", "hoss" (instead of "horse"), and "ye" (instead of "you") and spitting tobacco juice on animals and victims.[9] The characters of Wales, the Cherokee chief, Navajo woman, and the old settler woman and her daughter all appeared in the novel.[10] On the other hand, Kaufman was less happy with the novel's political stance; he felt that it had been "written by a crude fascist" and that "the man's hatred of government was insane".[6] He also felt that that element of the script needed to be severely toned down, but, he later said, "Clint didn't, and it was his film".[6] Kaufman was later fired by Eastwood, who took over the film's direction himself.

Cinematographer Bruce Surtees, James Fargo, and Fritz Manes scouted for locations and eventually found sites in Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, and Oroville, California even before they saw the final script.[10] The movie was shot in DeLuxe Color and Panavision.[5] Kaufman cast Chief Dan George, who had been nominated for an Academy Award for Supporting Actor in Little Big Man, as the old Cherokee Lone Watie. Sondra Locke, also a previous Academy Award nominee, was cast by Eastwood against Kaufman's wishes[11] as Laura Lee, the granddaughter of the old settler woman; at 32 she was a decade older than the character. This marked the beginning of a professional and domestic relationship between Eastwood and Locke that would span six films and last into the late 1980s. Ferris Webster was hired as the film's editor and Jerry Fielding as composer.

In June 1975, it was announced that Eastwood would star in the film with a scheduled Bicentennial Celebration release.[12] Principal photography began on October 6 in Lake Powell and nearby Paria, Utah.[13][11] A rift between Eastwood and Kaufman developed during the filming. Kaufman insisted on filming with a meticulous attention to detail, which caused disagreements with Eastwood, not to mention the attraction the two shared towards Locke and apparent jealousy on Kaufman's part in regard to their emerging relationship.[14] One evening, Kaufman insisted on finding a beer can as a prop to be used in a scene, but while he was absent, Eastwood ordered Surtees to quickly shoot the scene as light was fading and then drove away, leaving before Kaufman had returned.[15] Soon after, filming moved to Kanab, Utah. On October 24, 1975, Kaufman was fired at Eastwood's command by producer Bob Daley.[16] The sacking caused an outrage amongst the Directors Guild of America and other important Hollywood executives, since the director had already worked hard on the film, including completing all of the pre-production.[16] Pressure mounted on Warner Bros. and Eastwood to back down, and their refusal to do so resulted in a fine, reported to be around $60,000, for the violation.[16] This resulted in the Director's Guild passing a new rule, known as "the Eastwood Rule", which prohibits an actor or producer from firing the director and then personally taking on the director's role.[16] From then on, the film was directed by Eastwood himself with Daley as the second-in-command. With Kaufman's planning already in place, the team was able to finish making the film efficiently.

Reception

Critical response

"Eastwood is such a taciturn and action-oriented performer that it's easy to overlook the fact that he directs many of his movies—and many of the best, most intelligent ones. Here, with the moody, gloomily beautiful, photography of Bruce Surtees, he creates a magnificent Western feeling."

Roger Ebert[17]

Upon release in August 1976, The Outlaw Josey Wales was widely acclaimed by critics, many of whom saw Eastwood's role as an iconic one, relating it with much of America's ancestral past and the destiny of the nation after the American Civil War.[18] The film was pre-screened at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities in Idaho in a six-day conference entitled Western Movies: Myths and Images. Academics such as Bruce Jackson, critics such as Jay Cocks and Arthur Knight and directors such as King Vidor, Henry King, William Wyler and Howard Hawks were invited to the screening.[18] Time magazine named the film one of the year's top 10.[19] Roger Ebert compared the nature and vulnerability of Eastwood's portrayal of Josey Wales with his "Man with No Name" character in the Dollars Trilogy and praised the atmosphere of the film. On The Merv Griffin Show, Orson Welles lauded the film, calling Eastwood "one of America's finest directors".

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes retrospectively gave the film a 91% approval rating based on 43 reviews, with an average score of 8/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Recreating the essence of his iconic Man With No Name in a post-Civil War Western, director Clint Eastwood delivered the first of his great revisionist works of the genre."[20]

Awards

The Outlaw Josey Wales was nominated for the Academy Award for Original Music Score. In 1996, it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. It was also one of the few Western films to receive critical and commercial success in the 1970s at a time when the Western was thought to be dying as a major genre in Hollywood.

Clint Eastwood says on the 1999 DVD release that the movie is "certainly one of the high points of my career... in the Western genre of filmmaking".[citation needed]

Meaning

In 2011, Eastwood called The Outlaw Josey Wales an anti-war film.[21]

As for Josey Wales, I saw the parallels to the modern day at that time. Everybody gets tired of it, but it never ends. A war is a horrible thing, but it's also a unifier of countries... Man becomes his most creative during war. Look at the amount of weaponry that was made in four short years of World War II—the amount of ships and guns and tanks and inventions and planes and P-38s and P-51s, and just the urgency and the camaraderie, and the unifying. But that's kind of a sad statement on mankind, if that's what it takes.[21]

References

- ^ Munn, p. 156

- ^ "The Outlaw Josey Wales". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ Foote, John H. (2008). Clint Eastwood: Evolution of a Filmmaker. Westport, CT: Praeger. p. 32. ISBN 978-031335247-8.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1975). "The Outlaw Josey Wales". Film – Reviews. Variety. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ a b IMDB - The Outlaw Josie Wales

- ^ a b c Barra, Allen (December 20, 2001). "The Education of Little Fraud". Salon.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014.

- ^ Eleanor Mannikka (2015). "The Return of Josey Wales". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Baseline & All Movie Guide. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Is Forrest Carter Really Asa Carter? Only Josey Wales May Know for Sure". The New York Times. August 26, 1976. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

You could have fooled some of the people around here. They thought for sure that Forrest Carter, whose novel has become Clint Eastwood's current shoot-em-up movie "The Outlaw Josey Wales," is the man they knew as Asa Carter, a speech writer for Gov. George C. Wallace.

- ^ a b McGilligan (1999), p. 257

- ^ a b McGilligan (1999), p.258

- ^ a b McGilligan (1999), p.261

- ^ Gynter Quill (June 29, 1975). "'Gone to Texas' Packs Eastwood-Style Action". Waco Tribune-Herald.

- ^ "Clint Eastwood gets top role in outlaw film". Greeley Daily Tribune. Greeley, Colorado. July 7, 1975. p. 24.

- ^ McGilligan (1999), p. 262

- ^ McGilligan (1999), p. 263

- ^ a b c d McGilligan (1999), p. 264

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Outlaw Josey Wales".

- ^ a b McGilligan (1999), p.266

- ^ McGilligan (1999), p.267

- ^ "The Outlaw Josey Wales". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Judge, Michael (January 29, 2011). "A Hollywood Icon Lays Down the Law". Wall Street Journal.

Bibliography

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- Munn, Michael (1992). Clint Eastwood: Hollywood's Loner. London: Robson Books. ISBN 0-86051-790-X.

External links

- 1976 films

- 1970s English-language films

- American Western (genre) films

- Cherokee in popular culture

- 1976 Western (genre) films

- American Civil War films

- American films about revenge

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on Western (genre) novels

- Films based on works by Forrest Carter

- Films directed by Clint Eastwood

- Films scored by Jerry Fielding

- Films set in ghost towns

- Films set in Missouri

- Films set in Oklahoma

- Films set in Texas

- Films shot in Wyoming

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films shot in Utah

- Malpaso Productions films

- Films about Native Americans

- United States National Film Registry films

- Warner Bros. films

- Revisionist Western (genre) films

- American vigilante films

- Anti-war films

- Guerrilla warfare in film

- 1970s American films