Vaginismus

| Vaginismus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vaginism, genito-pelvic pain disorder[1] |

| |

| Muscles included | |

| Specialty | Gynecology, Urology, Sexual Medicine |

| Symptoms | Pain with sex[2] |

| Usual onset | With first sexual intercourse[3] |

| Causes | Fear of pain[3] |

| Risk factors | History of sexual assault, endometriosis, vaginitis, prior episiotomy[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on the symptoms and examination[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Dyspareunia,[4] Vulvodynia[5] |

| Treatment | Behavior therapy, gradual vaginal dilatation[2] |

| Prognosis | Generally good with treatment[6] |

| Frequency | 1-7% of the female population[5] |

Vaginismus is a condition in which involuntary muscle spasm interferes with vaginal intercourse or other penetration of the vagina.[2] This often results in pain with attempts at sex.[2] Often it begins when vaginal intercourse is first attempted.[3] Vaginismus may be considered an older term for pelvic floor dysfunction.[7]

The formal diagnostic criteria specifically require interference during vaginal intercourse and a desire for intercourse, but the term vaginismus is sometimes used more broadly to refer to any muscle spasm occurring during the insertion of objects into the vagina, sexually motivated or otherwise, including speculums and tampons.[6][8]

The underlying cause is generally a fear that penetration will hurt.[3] Risk factors include a history of sexual assault, endometriosis, vaginitis, or a prior episiotomy.[2] Diagnosis is based on the symptoms and examination.[2] It requires there to be no anatomical or physical problems (e.g., pelvic floor dysfunction, vulvodynia, vestibulodynia, etc) and a desire for penetration.[3][9]

Treatment may include behavior therapy such as graduated exposure therapy and gradual vaginal dilation.[2][3] Surgery is not generally indicated.[6] Botulinum toxin (botox), a muscle spasm treatment, is being studied.[2] There are no epidemiological studies of the prevalence of vaginismus.[10] Estimates of how common the condition is are varied.[11] One textbook estimates that 0.5% of women are affected,[2] but rates in clinical settings indicate that 5%–17% of women experience vaginismus.[10] Outcomes are generally good with treatment.[6]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Physical symptoms may include burning, and sharp pain or pressure in and around the vagina upon penetration.[12] Psychological symptoms include increased anxiety.[12] Pain during vaginal penetration varies.[13]

Despite being fairly common, there is low social awareness of vaginismus and women have difficulty finding support, even through the healthcare system.[14] A 2023 integrative review found that studies on vaginismus show it often takes years to receive a diagnosis.[14]

Causes

[edit]Primary vaginismus

[edit]Vaginismus occurs when penetrative sex or other vaginal penetration cannot be experienced without pain. It is commonly discovered among teenage girls and women in their early twenties, as this is when many girls and young women first attempt to use tampons, have penetrative sex, or undergo a Pap smear. Awareness of vaginismus may not happen until vaginal penetration is attempted. Reasons for the condition may be unknown.[15]

A few of the main factors that may contribute to primary vaginismus include:

- chronic pain conditions like vulvodynia and harm-avoidance behavior[16]

- negative emotional reaction toward sexual stimulation, e.g. disgust both at a deliberate level and a more implicit level[17]

- strict conservative moral education, which also can elicit negative emotions[18]

The cause of primary vaginismus is often unknown.[19]

Lamont has classified vaginismus[20] by severity. Lamont describes four degrees of vaginismus: In first-degree vaginismus, the person's pelvic floor has a spasm that can be relieved by reassurance. In second-degree, the spasm is present but maintained throughout the pelvis even with reassurance. In third-degree, the person elevates the buttocks to avoid being examined. In fourth-degree (also known as grade 4) vaginismus, the severest form, the person elevates the buttocks, retreats, and tightly closes the thighs to avoid examination. Pacik expanded Lamont's classification to include a fifth degree, in which the person experiences a visceral reaction such as sweating, hyperventilation, palpitations, trembling, shaking, nausea, vomiting, losing consciousness, wanting to jump off the table, or attacking the doctor.[21]

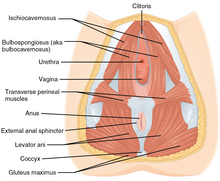

Although the pubococcygeus muscle is commonly thought to be the primary muscle involved in vaginismus, Pacik identified two more spastic muscles in people who were treated under sedation. These include the entry muscle (bulbocavernosum) and the mid-vaginal muscle (puborectalis). Spasm of the entry muscle accounts for the common complaint that people often report when trying to have intercourse: "It's like hitting a brick wall".[15]

Secondary vaginismus

[edit]Secondary vaginismus occurs when a person who has previously been able to achieve penetration develops vaginismus. This may be due to physical causes, such as a yeast infection or trauma during childbirth, psychological causes, or a combination of causes. The treatment for secondary vaginismus is the same as for primary vaginismus, although, in these cases, previous experience with successful penetration can assist in resolution of the condition. Peri-menopausal and menopausal vaginismus, often due to a drying of the vulvar and vaginal tissues as a result of reduced estrogen, may occur as a result of "micro-tears" first causing sexual pain then leading to vaginismus.[22]

Mechanism

[edit]Specific muscle involvement is unclear, but the condition may involve the levator ani, bulbocavernosus, circumvaginal, or perivaginal muscles.[11]

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of vaginismus, as well as other diagnoses of female sexual dysfunction, can be made when "symptoms are sufficient to result in personal distress."[23] The DSM-IV-TR defines vaginismus as "recurrent or persistent involuntary spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina that interferes with sexual intercourse, causing marked distress or interpersonal difficulty".[23]

Treatment

[edit]A 2012 Cochrane review found little high-quality evidence regarding the treatment of vaginismus.[24] Specifically, it is unclear whether systematic desensitisation is better than other measures, including nothing.[24]

Psychological

[edit]According to a 2011 study, those with vaginismus are twice as likely to have a history of childhood sexual interference and held less positive attitudes about their sexuality, whereas no correlation was noted for lack of sexual knowledge or (nonsexual) physical abuse.[25]

Physical

[edit]

Often, when faced with a person experiencing painful intercourse, a gynecologist will recommend reverse Kegel exercises and provide lubricants.[26][27][28] Although vaginismus has not been shown to affect a person's ability to produce lubrication, additional lubricant can be helpful in achieving penetration. This is because women may not produce natural lubrication if anxious or in pain. Achieving sufficient arousal during foreplay is crucial for the release of lubrication, which can ease sexual penetration and pain-free intercourse.

Strengthening exercises such as Kegel exercises were previously considered a helpful intervention for pelvic pain, but new research suggests that these exercises, which strengthen the pelvic floor, may not be helpful or may make conditions caused by overactive muscles such as vaginismus worse. Exercises that stretch or relax the pelvic floor may be a better treatment option for vaginismus.[29][30][31]

To help develop a treatment plan that best fits their patient's needs, a gynecologist or general practitioner may refer a person experiencing painful intercourse to a physical therapist or occupational therapist. These therapists specialize in the treatment of disorders of the pelvic floor muscles, such as vaginismus, pelvic floor dysfunction, dyspareunia, vulvodynia, constipation, and fecal or urinary incontinence.[30][31] After performing a manual exam internally and externally to assess muscle function and isolate possible trigger points for pain or muscle tightness, therapists develop a treatment plan consisting of muscle exercises, muscle stretches, dilator training, electrostimulation, and/or biofeedback.[30] Treatment of vaginismus often involves Hegar dilators (sometimes called vaginal trainers), progressively increasing the size of the dilator inserted into the vagina. The technique is used to practice conscious diaphragmatic breathing (breathing in deeply allowing one's belly to expand) and allowing the pelvic floor muscles to lengthen during inhale; then exhale, bringing belly in and repeat.[32][33] Research suggests pelvic floor physical or occupational therapy is one of the safest and most effective treatments for vaginismus.[31]

Many people find vaginal trainers like dilators helpful, but some often need more information on how to use them than is provided, or also seek out lubricant, topical anaesthetic or escitalopram,[14] a medicine commonly used to treat depression and anxiety.[34]

Neuromodulators

[edit]Botulinum toxin A (Botox) has been considered as a treatment option, with the idea of temporarily reducing the hypertonicity of the pelvic floor muscles. No random controlled trials have been done with this treatment, but experimental studies with small samples have found it effective, with sustained positive results through 10 months.[11][35] Similar in its mechanism of treatment, lidocaine has also been tried as an experimental option.[11][36]

Anxiolytics and antidepressants are other pharmacotherapies that have been offered to people in conjunction with other psychotherapy modalities and to people with high levels of anxiety from their condition.[11] Evidence for these medications is limited.[11]

Epidemiology

[edit]There are no epidemiological studies of the prevalence of vaginismus.[10] Estimates of how common the condition is varies.[11] A 2016 textbook estimated about 0.5% of women are affected,[2] while rates in Morocco and Sweden were estimated at 6%.[37]

Among those who attend clinics for sexual dysfunction, rates may be as high as 12% to 47%.[2][38]

History

[edit]The term vaginismus was developed by James Marion Sims in 1866 to describe the “hymeneal hyperaethesia with a spasmodic contraction of the sphincter vaginae” that, under examination, “will produce such agony as to cause the patient to shriek out, complaining at the same time that the pain is that of thrusting a sharp knife into the sensitive part.”[39] At that time, the condition was understood to be biological in origin and medically treatable. During the 1930-1960s, under the influence of Freudian psychology, gynecologists increasingly understood vaginismus as psychological in origin. As psychology turned away from Freudian ideas and toward behaviorism, the condition was re-cast as a learned fear or anxiety response.[40]

In popular culture

[edit]The Netflix miniseries Unorthodox depicted a young woman suffering from extreme pain during intercourse, which she was told was due to vaginismus.

The comedy feature film Lady Parts's main character struggles with painful sex and later is diagnosed with vaginismus.[41][42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Maddux, James E.; Winstead, Barbara A. (2012). Psychopathology: Foundations for a Contemporary Understanding. Taylor & Francis. p. 332. ISBN 9781136482847.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1330. ISBN 9780323448383.

- ^ a b c d e f "Vaginismus". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. April 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Domino, Frank J. (2010). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2011. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1394. ISBN 9781608312597.

- ^ a b Laskowska, A; Gronowski, P (2022). "Vaginismus: an overview". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 19 (5): S228-S229. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.03.520. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Vaginismus". NHS. 2018-01-11. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Yee, Alyssa; Uloko, Maria. "Female Sexual Dysfunction: Medical and Surgical Management of Pelvic Pain and Dyspareunia". Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Nazario, Brunilda, MD. (2012). "Women's Health: Vaginismus". WebMD. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Braddom, Randall L. (2010). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 665. ISBN 978-1437735635.

- ^ a b c Lahaie M-A, Boyer SC, Amsel R, Khalifé S, Binik YM. Vaginismus: A Review of the Literature on the Classification/Diagnosis, Etiology and Treatment. Women’s Health. 2010;6(5):705-719. doi:10.2217/WHE.10.46

- ^ a b c d e f g Lahaie, MA; Boyer, SC; Amsel, R; Khalifé, S; Binik, YM (Sep 2010). "Vaginismus: a review of the literature on the classification/diagnosis, etiology and treatment". Women's Health. 6 (5): 705–19. doi:10.2217/whe.10.46. PMID 20887170.

- ^ a b Katz, Ditza (2020). "Vaginismus: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment". Women's Therapy Center. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- ^ Reissing, Elke; Yitzchak Binik; Samir Khalife (May 1999). "Does Vaginismus Exist? A Critical Review of the Literature". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 187 (5): 261–274. doi:10.1097/00005053-199905000-00001. PMID 10348080.

- ^ a b c Pithavadian, Rashmi; Chalmers, Jane; Dune, Tinashe (January 2023). "The experiences of women seeking help for vaginismus and its impact on their sense of self: An integrative review". Women's Health. 19. doi:10.1177/17455057231199383. ISSN 1745-5057. PMC 10540594. PMID 37771119.

- ^ a b Pacik PT (December 2009). "Botox treatment for vaginismus". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124 (6): 455e–6e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bf7f11. PMID 19952618.

- ^ Borg, Charmaine; Peters, L. M.; Weijmar Schultz, W.; de Jong, P. J. (February 2012). "Vaginismus: Heightened Harm Avoidance and Pain Catastrophizing Cognitions". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9 (2): 558–567. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02535.x. PMID 22024378. S2CID 22249757.

- ^ Borg, Charmaine; Peter J. De Jong; Willibrord Weijmar Schultz (June 2010). "Vaginismus and Dyspareunia: Automatic vs. Deliberate: Disgust Responsivity". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7 (6): 2149–2157. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01800.x. PMID 20367766.

- ^ Borg, Charmaine; Peter J. de Jong; Willibrord Weijmar Schultz (Jan 2011). "Vaginismus and Dyspareunia: Relationship with General and Sex-Related Moral Standards". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (1): 223–231. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02080.x. PMID 20955317.

- ^ "Vaginismus". Sexual Pain Disorders and Vaginismus. Armenian Medical Network. 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Lamont, JA (1978). "Vaginismus". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 131 (6): 633–6. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(78)90822-0. PMID 686049.

- ^ Pacik, PT.; Cole, JB. (2010). When Sex Seems Impossible. Stories of Vaginismus and How You Can Achieve Intimacy. Odyne Publishing. pp. 40–7.

- ^ Pacik, Peter (2010). When Sex Seems Impossible. Stories of Vaginismus & How You Can Achieve Intimacy. Manchester, NH: Odyne. pp. 8–16. ISBN 978-0-9830134-0-2. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ^ a b American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology (April 2011). "Practice Bulletin No. 119: Female Sexual Dysfunction". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 117 (4): 996–1007. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31821921ce. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 21422879.

- ^ a b Melnik, T; Hawton, K; McGuire, H (12 December 2012). "Interventions for vaginismus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD001760. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001760.pub2. PMC 7072531. PMID 23235583.

- ^ Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D, Amsel R (2003). "Etiological correlates of vaginismus: sexual and physical abuse, sexual knowledge, sexual self-schema, and relationship adjustment". J Sex Marital Ther. 29 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1080/713847095. PMID 12519667. S2CID 46659017.

- ^ "When sex hurts – vaginismus". The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada. n.d. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20.

- ^ Nazario, Brunilda, MD. (2012). "Women's Health: Vaginismus". WebMD. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "When sex gives more pain than pleasure". Harvard Health Publications. Harvard Health. May 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Bradley, Michelle H.; Rawlins, Ashley; Brinker, C. Anna (August 2017). "Physical Therapy Treatment of Pelvic Pain". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 28 (3): 589–601. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2017.03.009. PMID 28676366.

- ^ a b c Rosenbaum, Talli Yehuda (January 2007). "REVIEWS: Pelvic Floor Involvement in Male and Female Sexual Dysfunction and the Role of Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in Treatment: A Literature Review". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 4 (1): 4–13. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00393.x. PMID 17233772.

- ^ a b c Wallace, Shannon L.; Miller, Lucia D.; Mishra, Kavita (December 2019). "Pelvic floor physical therapy in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction in women". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 31 (6): 485–493. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000584. ISSN 1040-872X. PMID 31609735. S2CID 204703488.

- ^ Doleys, Daniel (6 December 2012). Behavioral Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 377. ISBN 9781468440706.

- ^ nhs, nhs (2015). "NHS Choices Vaginal Trainers to treat vaginismus". NHS Choices Vaginismus treatment. NHS.

- ^ "Escitalopram: medicine to treat depression and anxiety". nhs.uk. 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ Pacik PT (2011). "Vaginismus: A Review of Current Concepts and Treatment using Botox Injections, Bupivacaine Injections and Progressive Dilation Under Anesthesia". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Journal. 35 (6): 1160–1164. doi:10.1007/s00266-011-9737-5. PMID 21556985. S2CID 8754988.

- ^ Melnik, T; Hawton, K; McGuire, H (Dec 12, 2012). "Interventions for vaginismus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD001760. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001760.pub2. PMC 7072531. PMID 23235583.

- ^ Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bosch R, et al. (July 2004). "Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction". J Sex Med. 1 (1): 35–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.565.3552. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10106.x. PMID 16422981.

- ^ Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S (May 1999). "Does vaginismus exist? A critical review of the literature". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 187 (5): 261–74. doi:10.1097/00005053-199905000-00001. PMID 10348080.

- ^ Sims, James Marion (1866). Clinical notes on uterine surgery: with special reference to the management of the sterile condition. New York: William Wood & Co. pp. 315, 318.

- ^ Srajer, Hannah (2023). "Imperfect Intercourse: Sexual Disability, Sexual Deviance, and the History of Vaginal Pain in the Twentieth-Century United States". Journal of American History. 109 (4): 782–803. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaad001. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Lady Parts Film Trailer". Intimate Rose. Retrieved 2024-04-26.

- ^ O'Malley, Sheila (2024-04-25). "A conversation with Bonnie Gross, Lady Parts screenwriter". The Sheila Variations 2.0. Retrieved 2024-04-26.