Appendix (anatomy)

| Vermiform Appendix | |

|---|---|

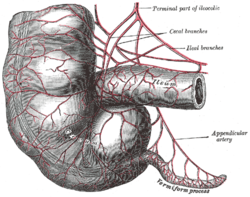

Arteries of cecum and vermiform appendix (appendix visible at lower right, labeled as "vermiform process") | |

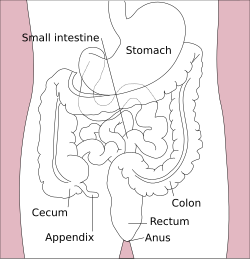

Normal location of the appendix relative to other organs of the digestive system (frontal view) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Midgut |

| System | Digestive |

| Artery | appendicular artery |

| Vein | appendicular vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | appendix vermiformis |

| MeSH | D001065 |

| TA98 | A05.7.02.007 |

| TA2 | 2976 |

| FMA | 14542 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The appendix (or vermiform appendix; also cecal [or caecal] appendix; also vermix) is a blind-ended tube connected to the cecum (or caecum), from which it develops embryologically. The cecum is a pouchlike structure of the colon. The appendix is located near the junction of the small intestine and the large intestine.

The term "vermiform" comes from Latin and means "worm-shaped".

It is widely present in the Euarchontoglires and has also evolved independently in the diprotodont marsupials and is highly diverse in size and shape.[1]

Size and location in humans

The appendix averages 11 cm in length but can range from 2 to 20 cm. The diameter of the appendix is usually between 7 and 8 mm. The longest appendix ever removed measured 26 cm from a patient in Zagreb, Croatia.[2] The appendix is located in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, near the right hip bone.[3] Its position within the abdomen corresponds to a point on the surface known as McBurney's point (see below). While the base of the appendix is at a fairly constant location, 2 cm below the ileocecal valve,[3] the location of the tip of the appendix can vary from being retrocecal (behind the cecum) (74%)[3] to being in the pelvis to being extraperitoneal. In rare individuals with situs inversus, the appendix may be located in the lower left side.

Vestigiality

The human appendix is a vestigial structure. A vestigial structure is a structure that has lost all or most of its original function through the process of evolution. The vermiform appendage is the shrunken remainder of the cecum that was found in a remote ancestor of humans. Ceca, which are found in the digestive tracts of many extant herbivores, house mutualistic bacteria which help animals digest the cellulose molecules that are found in plants.[4] As the human appendix no longer houses a significant number of these bacteria, and humans are no longer capable of digesting more than a minimal amount of cellulose per day,[5] the human appendix is considered a vestigial structure. This interpretation would stand even if it were found to have a certain use in the human body. Vestigial organs are sometimes pressed into a secondary use when their original function has been lost.[6] See the sections below for possible functions of the appendix that may have evolved more recently after the appendix lost its original function.

A possible scenario for the progression from a fully functional cecum to the current human appendix was put forth by Charles Darwin.[7] He suggested that the appendix was used for digesting leaves as primates. It may be a vestigial organ, evolutionary baggage, of ancient humans that has degraded down to nearly nothing over the course of evolution. The very long cecum of some herbivorous animals, such as found in the horse or the koala, supports this theory. The koala's cecum enables it to host bacteria that specifically help to break down cellulose. Human ancestors may have also relied upon this system when they lived on a diet rich in foliage. As people began to eat more easily digested foods, they became less reliant on cellulose-rich plants for energy. As the cecum became less necessary for digestion, mutations that were previously deleterious (and would have hindered evolutionary progress) were no longer important, so the mutations have survived. These alleles became more frequent and the cecum continued to shrink. After thousands of years, the once-necessary cecum has degraded to be the appendix of today.[7] On the other hand, evolutionary theorists have suggested that natural selection selects for larger appendices because smaller and thinner appendices would be more susceptible to inflammation and disease.[8]

Possible functions

Immune function

Some scientists have recently proposed that the appendix may harbour and protect bacteria that are beneficial in the function of the human colon.[9]

Loren G. Martin, a professor of physiology at Oklahoma State University, argues that the appendix has a function in fetuses and adults.[10] Endocrine cells have been found in the appendix of 11-week-old fetuses that contribute to "biological control (homeostatic) mechanisms." In adults, Martin argues that the appendix acts as a lymphatic organ. The appendix is experimentally verified as being rich in infection-fighting lymphoid cells, suggesting that it might play a role in the immune system. Zahid[11] suggests that it plays a role in both manufacturing hormones in fetal development as well as functioning to "train" the immune system, exposing the body to antigens so that it can produce antibodies. He notes that doctors in the last decade have stopped removing the appendix during other surgical procedures as a routine precaution, because it can be successfully transplanted into the urinary tract to rebuild a sphincter muscle and reconstruct a functional bladder.

Maintaining gut flora

Although it was long accepted that the immune tissue, called gut associated lymphoid tissue, surrounding the appendix and elsewhere in the gut carries out a number of important functions, explanations were lacking for the distinctive shape of the appendix and its apparent lack of importance as judged by an absence of side effects following appendectomy.[12]

William Parker, Randy Bollinger, and colleagues at Duke University proposed that the appendix serves as a haven for useful bacteria when illness flushes those bacteria from the rest of the intestines.[9][13] This proposal is based on a new understanding of how the immune system supports the growth of beneficial intestinal bacteria,[14][15] in combination with many well-known features of the appendix, including its architecture, its location just below the normal one-way flow of food and germs in the large intestine, and its association with copious amounts of immune tissue. Research performed at Winthrop University-Hospital showed that individuals without an appendix were four times more likely to have a recurrence of Clostridium difficile.[16]. However, other research showed that there is a significantly greater rate of C. difficile infection among people with an appendix, with more than 80% of the infections occurring among patients with an intact appendix [17].

Such a function may be useful in a culture lacking modern sanitation and healthcare practice, where diarrhea may be prevalent.[13] Current epidemiological data[18] show that diarrhea is one of the leading causes of death in developing countries.

Diseases

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2007) |

The most common diseases of the appendix (in humans) are appendicitis and carcinoid tumors (appendiceal carcinoid).[19] Appendix cancer accounts for about 1 in 200 of all gastrointestinal malignancies. In rare cases, adenomas are also present.[20]

Appendicitis (or epityphlitis) is a condition characterized by inflammation of the appendix. Pain often begins in the center of the abdomen, corresponding to the appendix's development as part of the embryonic midgut. This pain is typically a dull, poorly localized, visceral pain.[21]

As the inflammation progresses, the pain begins to localize more clearly to the right lower quadrant, as the peritoneum becomes inflamed. This peritoneal inflammation, or peritonitis, results in rebound tenderness (pain upon removal of pressure rather than application of pressure). In particular, it presents at McBurney's point, 1/3 of the way along a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. Typically, point (skin) pain is not present until the parietal peritoneum is inflamed, as well. Fever and an immune system response are also characteristic of appendicitis.[21]

Appendicitis requires removal of the inflamed appendix, either by laparotomy or laparoscopy. Untreated, the appendix may rupture, leading to peritonitis, followed by shock, and, if still untreated, death.[21]

The surgical removal of the vermiform appendix is called an appendectomy, or appendicectomy.[22] This removal is normally performed as an emergency procedure when the patient is suffering from acute appendicitis. In the absence of surgical facilities, intravenous antibiotics are used to delay or avoid the onset of sepsis; it is now recognized that many cases will resolve when treated without surgery.[dubious ] In some cases, the appendicitis resolves completely; more often, an inflammatory mass forms around the appendix. This is a relative contraindication to surgery.

Use as efferent urinary conduit

The appendix is used for the construction of an efferent urinary conduit, in an operation known as the Mitrofanoff procedure,[23] in people with a neurogenic bladder.

Use as access to colon in faecal incontinence (ACE and Chait tube)

The appendix is also used as a means to access the colon in children with paralysed bowels or major rectal sphincter problems. The appendix is brought out to the skin surface and the child/parent can then attach a catheter and easily wash out the colon (via normal defaecation) using an appropriate solution. See http://www.healthpoint.co.nz/default,169125.sm;jsessionid=1CD66A058B10550C51041E477C8E7075

Gallery

|

|

See also

References

- ^ SMITH, H. F., FISHER, R. E., EVERETT, M. L., THOMAS, A. D., RANDAL BOLLINGER, R. and PARKER, W. (2009), Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22: 1984–1999. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01809.x

- ^ "Guinness world record for longest appendix removed". Guinnessworldrecords.com. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ^ a b c Paterson-Brown, S. (2007). "15. The acute abdomen and intestinal obstruction". In Parks, Rowan W.; Garden, O. James; Carter, David John; Bradbury, Andrew W.; Forsythe, John L. R. (ed.). Principles and practice of surgery (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-10157-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Animal Structure & Function". Sci.waikato.ac.nz. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ^ Slavin, JL (1981). "Neutral detergent fiber, hemicellulose and cellulose digestibility in human subjects". Journal of Nutrition. 111 (2): 287–97.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McCabe, Joseph (1912). The Story of Evolution. London: Hutchinson & Co.

- ^ a b Darwin, Charles (1871) "Jim's Jesus". The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray: London.

- ^ "The old curiosity shop". New Scientist. 2008-05-17.

- ^ a b Associated Press. "Scientists may have found appendix's purpose". MSNBC, 5 October 2007. Accessed 17 March 2009.

- ^ "What is the function of the human appendix? Did it once have a purpose that has since been lost?". Scientific American. 1999-10-21. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ Zahid, A. (2004). "The vermiform appendix: not a useless organ". J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 14 (4): 256–8. PMID 15228837.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kumar, Vinay; Robbins, Stanley L.; Cotran, Ramzi S. (1989). Robbins' pathologic basis of disease (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 902–3. ISBN 0-7216-2302-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bollinger, R.R. (21 December 2007). "Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 249 (4): 826–831. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.08.032. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 17936308.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sonnenburg J.L., Angenent L.T., Gordon J.I. (2004). "Getting a grip on things: how do communities of bacterial symbionts become established in our intestine?". Nat. Immunol. 5 (6): 569–73. doi:10.1038/ni1079. PMID 15164016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Everett M.L., Palestrant D., Miller S.E., Bollinger R.R., Parker W. (2004). "Immune exclusion and immune inclusion: a new model of host-bacterial interactions in the gut". Clinical and Applied Immunology Reviews. 5: 321–32.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2012/01/02/your-appendix-could-save-your-life/

- ^ Merchant, R. (17 January 2012). "Association Between Appendectomy and Clostridium difficile Infection". J Clin Med Res. 4 (1): 17–19. doi:10.4021/jocmr770w. PMC 3279496. PMID 22383922.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Statistics on the cause of death in developed countries collected by the World Health Organization in 2001 show that acute diarrhea is now the fourth leading cause of disease-related death in developing countries (data summarized by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation).[citation needed] Two of the other leading causes of death are expected to have exerted limited or no selection pressure on humans in the distant past because one (HIV-AIDS) only very recently emerged and another (ischaemic heart disease) primarily affects people in their post-reproductive years. Thus, acute diarrhea may have been one of the primary disease-related selection pressures on the human population in the past. (Lower respiratory tract infection (pneumonia) is the remaining of the top four leading causes of disease-related death in third world countries.)

- ^ "Appendix disorders Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatments and Causes". Wrongdiagnosis.com. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ^ "Statistics about Appendix disorder". Wrongdiagnosis.com. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ^ a b c Miller R., Kenneth (2002). Biology. Prentice Hall. pp. 92–98. ISBN 0-13-050730-X.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "appendicectomy - definition of appendicectomy". Farlex Incorporation.

- ^ Mingin G.C., Baskin L.S. (2003). "Surgical management of the neurogenic bladder and bowel". Int Braz J Urol. 29 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1590/S1677-55382003000100012. PMID 15745470.

Further reading

- "The vestigiality of the human vermiform appendix: A Modern Reappraisal"—evolutionary biology argument that the appendix is vestigial

- Appendix May Actually Have a Purpose—2007 WebMD article

- Smith, H.F. (2009). "Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 22 (10): 1984–99. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01809.x. ISSN 1420-9101. PMID 19678866.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cho, Jinny. "Scientists refute Darwin's theory on appendix". The Chronicle (Duke University), August 27, 2009. (News article on the above journal article.)

External links

- Anatomy photo:37:12-0102 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"Abdominal Cavity: The Cecum and the Vermiform Appendix"