Lolita: Difference between revisions

m →Possible real-life prototype: unlink Frank La Salle, redirects to Florence Horner |

Uglinessman (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

[[The Police]]'s 1980 song "[[Don't Stand So Close to Me]]" refers to "just like the old man in that famous book by Nabokov," which in context is clearly ''Lolita''. The song is about a teacher having a relationship with a young student. Perhaps to fit the [[Meter (poetry)|meter]] of the song, or perhaps because of an error on the part of [[Sting (music)|Sting]], the song's writer, Nabokov's name is mispronounced, placing the stress on the first syllable. |

[[The Police]]'s 1980 song "[[Don't Stand So Close to Me]]" refers to "just like the old man in that famous book by Nabokov," which in context is clearly ''Lolita''. The song is about a teacher having a relationship with a young student. Perhaps to fit the [[Meter (poetry)|meter]] of the song, or perhaps because of an error on the part of [[Sting (music)|Sting]], the song's writer, Nabokov's name is mispronounced, placing the stress on the first syllable. |

||

A number of other songs have been based on the novel. [[Freedy Johnston]]'s song "Dolores" from the 1994 ''[[This Perfect World]]'' album refers to Lolita. [[Suzanne Vega]] included a song called "Lolita" on her 1996 album ''[[Nine Objects of Desire]]'', as did the band [[Elefant (band)|Elefant]] on their 2006 album ''[[The Black Magic Show]]'' and Prince in 2006's ''3121''. French singer [[Alizée]] released a song called "''[[Moi... Lolita]]''" in [[2000]]. |

A number of other songs have been based on the novel. [[Freedy Johnston]]'s song "Dolores" from the 1994 ''[[This Perfect World]]'' album refers to Lolita. [[Suzanne Vega]] included a song called "Lolita" on her 1996 album ''[[Nine Objects of Desire]]'', as did the band [[Elefant (band)|Elefant]] on their 2006 album ''[[The Black Magic Show]]'' and Prince in 2006's ''3121''. French singer [[Alizée]] released a song called "''[[Moi... Lolita]]''" in [[2000]]. The video for the song "Say It, Say It" by [[Elizabeth Daily|EG Daily]] is based on the 1962 film version, although the lyrics are only vaguely related. |

||

The case of [[Amy Fisher]], dubbed the "Long Island Lolita", helped popularize the term among a new generation. Screenwriter [[Alan Ball (screenwriter)|Alan Ball]] considered writing a play based on the Fisher case, but the story soon got away from him and mutated into the screenplay which became ''[[American Beauty (1999 movie)|American Beauty]]'' ([[1999 in film|1999]]). The narrator's name, Lester Burnham, is an [[anagram]] of "Humbert learns"; the name of the girl he lusts after, Angela Hayes, is also a play on Dolores Haze. |

The case of [[Amy Fisher]], dubbed the "Long Island Lolita", helped popularize the term among a new generation. Screenwriter [[Alan Ball (screenwriter)|Alan Ball]] considered writing a play based on the Fisher case, but the story soon got away from him and mutated into the screenplay which became ''[[American Beauty (1999 movie)|American Beauty]]'' ([[1999 in film|1999]]). The narrator's name, Lester Burnham, is an [[anagram]] of "Humbert learns"; the name of the girl he lusts after, Angela Hayes, is also a play on Dolores Haze. |

||

Revision as of 02:40, 21 February 2007

| Cover of the first British edition Cover art of the first British edition | |

| Author | Vladimir Nabokov |

|---|---|

| Language | English, Russian |

| Genre | Tragicomedy, novel |

| Publisher | Olympia Press, G. P. Putnam's, McGraw-Hill, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Fawcett, Transworld (Corgi), Phaedra |

Publication date | 1955 |

| Publication place | |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 368 pp (recent paperback edition) |

| ISBN | ISBN 1-85715-133-X (recent paperback edition) Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

Lolita (1955) is a novel by Vladimir Nabokov. The novel was first written in English and published in 1955 in Paris, later translated by the author into Russian and published in 1967 in New York. The novel is both internationally famous for its innovative style and infamous for its controversial subject: the book's narrator and protagonist Humbert Humbert becoming sexually obsessed with a pre-pubescent twelve-year-old girl named Dolores Haze.

After its publication, the novel attained a classic status, becoming one of the best known, and perhaps controversial examples of 20th century literature. The name "Lolita" has entered pop culture to describe a sexually precocious young girl.

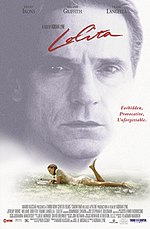

The novel was adapted to film twice, once in 1962 by Stanley Kubrick starring James Mason as Humbert Humbert, and again in 1997 by Adrian Lyne, starring Jeremy Irons.

Plot summary

Template:Spoiler Humbert Humbert is a Swiss scholar of literature, born in 1910 in Paris, France and raised here by his wealthy, widower father after his young mother is killed by lightning. Humbert is tormented by a passion for what he calls 'nymphets' (sexually desirable pre-adolescent girls), which he believes was caused by his failure to consummate an affair with a childhood sweetheart, named Annabel, before her premature death from typhus. After a ridiculously failed marriage, he leaves Paris for New York shortly before the start of World War II, during which he writes a textbook of French literature. In 1947 he moves to Ramsdale, a small New England town, to write. By mischance he rents a room in the home of Charlotte Haze, a widow, but only after first seeing her twelve-year-old daughter Lolita (formally named Dolores) sunbathing in the garden. Humbert is instantly besotted by her, and does anything to be near her, including putting up with her mother, whom he dislikes. Gradually, the living Lolita supplants the memory of his childhood love completely.

Charlotte becomes his unwitting pawn in his quest to make Lolita a part of his living fantasy. When Mrs. Haze drives Lolita off to summer camp, she leaves an ultimatum for Humbert, saying that he must marry her (for she has fallen madly in love with him) or move out. Humbert chooses the former solely to make Lolita his stepdaughter, intending to use heavy sedatives on both her and her mother so he can molest Lolita in her sleep, his intention being to prevent the corruption of her innocence. Humbert starts to write a diary recording his life in Ramsdale, and more specifically his relationship with Lolita, which he locks in a drawer of one of Charlotte's tables. While Humbert is in town and Lolita is away at camp, Charlotte manages to open the drawer and finds his diary, which details his lack of interest in Charlotte and impassioned lust for her daughter. Horrified and humiliated, Charlotte decides to flee with Lolita. Before doing so, she writes three letters - to Humbert, Lolita, and a strict boarding school to which she apparently intended to send her daughter. Charlotte confronts Humbert when he returns home. Retreating to the kitchen, he tells her that the diary entries are just notes for a novel. Charlotte, meanwhile, leaves the house in order to post the letters. Crossing the street, she is struck and killed by a passing motorist. A child retrieves the letters and gives them to Humbert, who destroys them.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp and takes her to The Enchanted Hunters, a hotel of regional repute, intending to use the sleeping pills on her. They have little effect on her, however. She instead seduces Humbert (the first of only two times she is recorded as doing so) -- and he discovers that he isn't her first lover, having had a sexual affair at summer camp with the son of the camp mistress. Traumatized to learn of her mother's death, Lolita initially surrenders to Humbert's carnal demands. Later he must resort to bribery as he drives her around the country in Charlotte's car, moving from state to state. Eventually they settle down in another New England town, with Humbert posing as Lolita's father. After a stay of some months, however, they resume their travels. Humbert is puzzled and guarded, sure that they are being followed and that she is seeing someone else. He is right: playwright Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte's, and himself a pedophile and amateur pornographer, is tailing the couple in accordance with Lolita's secret plan of escape, which is successful. Humbert, still clueless as to Quilty's identity, remains unaware of their whereabouts in spite of his farcical attempts to find them.

During this period Humbert has a chaotic, two year love-affair with an alcoholic named Rita, who at thirty is ten years younger than himself and a passable substitute for Lolita. By 1952 Humbert has settled down as a scholar at a small academic institute. One day he receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is now married, pregnant, and in need of funds. Armed with a gun, Humbert, still driving Charlotte's car, tracks her down. She tells him that her husband, a nearly deaf war-veteran and the father of her child, was not her abductor. Humbert offers to give Lolita his entire financial worth if she will reveal his identity. Lolita tells Humbert what he wants to know, and of Quilty's attempt to force her into pornographic films involving young boys. Lolita maintains that she merely wanted to be near the man she loved -- Quilty, not Humbert. Leaving Lolita forever, Humbert surprises Quilty in his house. Quilty slowly begins to go insane when he sees Humbert's gun. After a mutually exhausting struggle for it, Quilty, now fully mad with fear, merely responds politely as Humbert shoots him, and Quilty dies with a comical lack of interest. Humbert is unamused and disoriented. Arrested for murder, he writes the book he entitles Lolita, or The Confessions of a White Widowed Male, while awaiting trial. Upon finishing, he dies, of coronary thrombosis. Lolita leaves with her husband to the remote Northwest, by means of Humbert's financial aid, where she too dies, during childbirth, on Christmas Day, 1952.

Style and interpretation

The novel is a tragicomedy narrated by Humbert, who riddles the narrative with wordplay and his wry observations of American culture. His humor provides an effective counterpoint to the pathos of the tragic plot. The novel's flamboyant style is characterized by word play, double entendres, multilingual puns, anagrams, and coinages such as nymphet, a word which has since had a life of its own and can be found in most dictionaries, and the lesser used "faunlet". Nabokov's Lolita is far from an endorsement of pedophilia, since it dramatizes the tragic consequences of Humbert's obsession with the young heroine. Nabokov himself described Humbert as "a vain and cruel wretch" and "a hateful person" (quoted in Levine, 1967).

Humbert is a well-educated, multilingual, literary-minded European émigré. He fancies himself a great artist, but lacks the curiosity that Nabokov considers essential. Humbert tells the story of a Lolita that he creates in his mind because he is unable and unwilling to listen to the actual girl and accept her on her own terms. In the words of Richard Rorty, from his famous interpretation of Lolita in Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Humbert is a "monster of incuriosity".

Some critics have accepted Humbert's version of events at face value. In 1959, novelist Robertson Davies excused the narrator entirely, writing that the theme of Lolita is "not the corruption of an innocent child by a cunning adult, but the exploitation of a weak adult by a corrupt child".

Most writers, however, have given less credit to Humbert and more to Nabokov's powers as an ironist. Martin Amis, in his essay on Stalinism, Koba the Dread, proposes that Lolita is an elaborate metaphor for the totalitarianism which destroyed the Russia of Nabokov's childhood (though Nabokov states in his Afterword that he "[detests] symbols and allegories"). Amis interprets it as a story of tyranny told from the point of view of the tyrant. "All of Nabokov's books are about tyranny," he says, "even Lolita. Perhaps Lolita most of all".

In 2003, Iranian expatriate Azar Nafisi published the memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran about an illicit women's reading group. In this book the psychological and political interpretations of Lolita are united, since as female intellectuals in Iran, Nafisi and her students were denied both public liberty and private sexual selfhood. Although rejecting a too-easy identification of Lolita's captivity with that of her students ("...we were not Lolita, the Ayatollah was not Humbert...") Nafisi writes of her students' strong emotional connection with the book: "what linked us so closely was this perverse intimacy of victim and jailer" and "like Lolita we tried to escape and create our own little pockets of freedom".

For Nafisi the essence of the novel is Humbert's solipsism and his erasure of Lolita's independent identity. She writes: "Lolita was given to us as Humbert's creature [...] To reinvent her, Humbert must take from Lolita her own real history and replace it with his own [...] Yet she does have a past. Despite Humbert's attempts to orphan Lolita by robbing her of her history, that past is still given to us in glimpses".

One of the novel's early champions, Lionel Trilling, warned in 1958 of the moral difficulty in interpreting a book with so eloquent and so self-deceived a narrator: "we find ourselves the more shocked when we realize that, in the course of reading the novel, we have come virtually to condone the violation it presents [...] we have been seduced into conniving in the violation, because we have permitted our fantasies to accept what we know to be revolting".

Publication and reception

Due to its subject matter, Nabokov was unable to find an American publisher for Lolita. After four refused, he finally resorted to the Olympia Press in Paris. Although the first printing of 5,000 copies sold out, there were no substantial reviews. Eventually, at the end of 1954, Graham Greene, in an interview with the (London) Times, called it one of the best novels of 1954. This statement provoked a response from the (London) Sunday Express whose editor called it "the filthiest book I have ever read" and "sheer unrestrained pornography." British Customs officers were then instructed by a panicked Home Office to seize all copies entering the United Kingdom. In December 1956 the French followed suit and the Minister of the Interior banned Lolita (the ban lasted for two years).

By complete contrast American officials were initially nervous but the first American edition was issued without problems by G.P.Putnam's Sons in 1958 and was a bestseller, the first book since Gone with the Wind to sell 100,000 copies in the first three weeks of publication.

Today, it is considered by many one of the finest novels written in the 20th century. In 1998, it was named the fourth greatest novel of the 20th century by the Modern Library. It was also named fourth in Time magazine's list of The 10 Greatest Books of All Time.[1]

The Enchanter

In 1985, The Enchanter, an English translation of a Nabokov novella originally titled Volshebnik (Волшебник) was published posthumously. Volshebnik was written in Russian, while Nabokov was living in France in 1939. It can be seen as an early version of Lolita but with significant differences: the action takes place in central Europe, and the protagonist is unable to consummate his passion with his step-daughter, leading to his suicide. It lacks the scope and wordplay of Lolita but is essential reading for anyone interested in the genesis of the book.

Allusions/references to other works

- Humbert Humbert's first love, Annabel Leigh, is named after the woman in the poem "Annabel Lee" by Edgar Allan Poe. In fact, their young love is described in phrases borrowed from Poe's poem. Nabokov originally intended Lolita to be called The Kingdom by the Sea [2], drawing on the rhyme with Annabel Lee that was used in the first verse of Poe's work. The conclusion of the first chapter – "Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, exhibit number one is what the seraphs, the misinformed, simple, noble-winged seraphs, envied. Look at this tangle of thorns." – is also a reference to the poem. ("With a love that the winged seraphs in heaven / Coveted her and me.")

- Humbert Humbert's double name recalls Poe's "William Wilson", a tale in which the main character is haunted by his doppelgänger, paralleling to the presence of Humbert's own doppelgänger, Clare Quilty. Humbert is not, however, his real name, but a chosen pseudonym (and perhaps a reference to binomial nomenclature).

- Humbert Humbert's field of expertise is French literature (one of his jobs is writing a series of educational works which compare French writers to English writers), and as such there are several references to French literature, including the authors Gustave Flaubert, Marcel Proust, François Rabelais, Charles Baudelaire, Prosper Mérimée and Pierre de Ronsard.

- In chapter 13, Humbert Humbert quotes "to hold thee lightly on a gentle knee and print on thy soft cheek a parent's kiss" from Lord Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

- In chapter 35, Humbert's "death sentence" on Clare Quilty parodies the rhythm and use of anaphora in T. S. Eliot's poem Ash Wednesday.

- The line "I cannot get out, said the starling" from Humbert's poem is taken from a passage in Laurence Sterne's A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, "The Passport, the Hotel De Paris."

Possible real-life prototype

According to Alexander Dolinin [3], the prototype of Lolita was 11-year-old Florence Horner, kidnapped in 1948 by a 50-year-old pedophile mechanic, Frank La Salle, who had caught her stealing a five-cent notebook. La Salle travelled with her over various states for 21 months and is believed to have had sex with her. He claimed that he was an FBI agent and threatened to “turn her in” for the theft and to send her to "a place for girls like you." The Horner case was not widely reported, but Dolinin adduces various similarities in events and descriptions.

The problem with this suggestion is that Nabokov had already used the same basic idea – that of a child molester and his victim booking into a hotel as man and daughter – in his then unpublished 1939 work Volshebnik (Волшебник). This not to say, however, that Nabokov could not have drawn on some details of the Florence Horner case in writing Lolita. In fact, the La Salle case is mentioned explicitly in the book, in Chapter 33 of Part II:

"(Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?)"

Heinz von Eschwege's "Lolita"

German academic Michael Maar's book The Two Lolitas (ISBN 1-84467-038-4) describes his recent discovery of a 1916 German short story titled "Lolita" about a middle-aged man travelling abroad who takes a room as a lodger and instantly becomes obsessed with the preteen girl (also named Lolita) who lives in the same house. Maar has speculated that Nabokov may have had cryptomnesia (a "hidden memory" of the story that Nabokov was unaware of) while he was composing Lolita during the 1950s. Maar says that until 1937 Nabokov lived in the same section of Berlin as the author, Heinz von Eschwege (pen name: Heinz von Lichberg), and was most likely familiar with his work, which was widely available in Germany during Nabokov's time there [4][5]. The Philadelphia Inquirer, in the article "Lolita at 50: Did Nabokov take literary liberties?" says that, according to Maar, accusations of plagiarism should not apply and quotes him as saying: "Literature has always been a huge crucible in which familiar themes are continually recast... Nothing of what we admire in Lolita is already to be found in the tale; the former is in no way deducible from the latter."

Nabokov's afterword

In 1956, Nabokov penned an afterword to Lolita ("On a Book Entitled Lolita") that was included in every subsequent edition of the book.

In the afterword, Nabokov wrote that "the initial shiver of inspiration" for Lolita "was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature's cage.” Neither the article nor the drawing has been recovered.

In response to an American critic who characterized Lolita as the record of Nabokov's "love affair with the romantic novel", Nabokov wrote that "the substitution of 'English language' for 'romantic novel' would make this elegant formula more correct.”

Nabokov concluded the afterword with a reference to his beloved first language, which he abandoned as a writer once he moved to the United States in 1940: "My private tragedy, which cannot, and indeed should not, be anybody's concern, is that I had to abandon my natural idiom, my untrammeled, rich, and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English."

Russian translation

Nabokov translated Lolita into Russian; the translation was published by Phaedra in New York in 1967.

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

Lolita has been filmed twice: the first adaptation was made in 1962 by Stanley Kubrick, and starred James Mason, Shelley Winters, Peter Sellers and, as Lolita, Sue Lyon; and a second adaptation in 1997 by Adrian Lyne, starring Jeremy Irons, Dominique Swain, and Melanie Griffith. Nabokov was nominated for an Academy Award for his work on the earlier film's adapted screenplay, although little of this work reached the screen. The more recent version was given mixed reviews by critics. It was delayed for over a year because of its controversiality, and also was not released in Australia until 1999.

The book was adapted into a musical in the 1971 by librettist/lyricist Alan Jay Lerner and composer John Barry under the title Lolita, My Love. Critics were surprised at how sensitively the story was translated to the stage, but the show nonetheless closed on the road before it opened in New York.

In 1982, Edward Albee adapted the book into a nonmusical play. It was savaged by critics, Frank Rich notably attributing the temporary death of Albee's career to it.

It is now also being filmed for a Bollywood movie, "Nishabd", acting in it are Amitabh Bachan and Jiah Khan

Influence on language

The term lolita has come to be used to refer to an adolescent girl considered to be very seductive, especially one younger than the age of consent. This meaning of the word is somewhat ironic in that the Lolita of the novel is described by both her mother and by Humbert as lacking conventional beauty. In Strong Opinions, Nabokov opines that he is "probably responsible" for parents not naming their children "Lolita" anymore. Indeed, the town of Lolita, Texas nearly changed its name after the novel gained notoriety.

In the book itself, "Lolita" is specifically Humbert's nickname for Dolores, and "nymphet" is the general term for the type of young girl to whom Humbert is attracted.

Allusions/references in other works

The Police's 1980 song "Don't Stand So Close to Me" refers to "just like the old man in that famous book by Nabokov," which in context is clearly Lolita. The song is about a teacher having a relationship with a young student. Perhaps to fit the meter of the song, or perhaps because of an error on the part of Sting, the song's writer, Nabokov's name is mispronounced, placing the stress on the first syllable.

A number of other songs have been based on the novel. Freedy Johnston's song "Dolores" from the 1994 This Perfect World album refers to Lolita. Suzanne Vega included a song called "Lolita" on her 1996 album Nine Objects of Desire, as did the band Elefant on their 2006 album The Black Magic Show and Prince in 2006's 3121. French singer Alizée released a song called "Moi... Lolita" in 2000. The video for the song "Say It, Say It" by EG Daily is based on the 1962 film version, although the lyrics are only vaguely related.

The case of Amy Fisher, dubbed the "Long Island Lolita", helped popularize the term among a new generation. Screenwriter Alan Ball considered writing a play based on the Fisher case, but the story soon got away from him and mutated into the screenplay which became American Beauty (1999). The narrator's name, Lester Burnham, is an anagram of "Humbert learns"; the name of the girl he lusts after, Angela Hayes, is also a play on Dolores Haze.

In the 2005 film Broken Flowers starring Bill Murray and directed by Jim Jarmusch, Alexis Dziena has a brief appearance as an overtly sexual teenage girl named Lolita. The central character Don (played by Murray) remarks about the ironic choice of name to Lolita and her mother, an old flame of his. Later in the film he meets a young woman called Sun Green; in the novel, Soleil Vert is mentioned as the name of Lolita's perfume.

In the comedic novel "Me Talk Pretty Someday" by David Sedaris who day dreams that he is a young white house intern who sleeps with the president and later writes "Lolita" because in his fantasy Nabokov never existed.

"Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books" is a literary memoir by Iranian author and professor, Azar Nafisi.

In the 1979 film Manhattan starring Woody Allen, a brief reference to Nabokov and Lolita is made. Woody's character is dating a 17-year-old girl. During the scene where his friends first meet her, one of them comments "Somewhere Nabokov is smiling."

In the song "Funny Face" by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Anthony Kiedis sings the line "Lo-lo-lo-Lolita, let her see me deep in love" an obvious reference to his girlfriend, who is much younger than Kiedis (18).

References

- Nabokov Library

- Appel, Alfred Jr. (1991). The Annotated Lolita (revised ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-72729-9.

- One of the best guides to the complexities of Lolita. First published by McGraw-Hill in 1970. (Nabokov was able to comment on Appel's earliest annotations, creating a situation which Appel described as being like John Shade revising Charles Kinbote's comments on Shade's poem Pale Fire. Oddly enough, this is exactly the situation Nabokov scholar Brian Boyd proposed to resolve the literary complexities of Nabokov's Pale Fire.)

- Levine, Peter (1967) "Lolita and Aristotle's Ethics" in Philosophy and Literature Volume 19, Number 1, April 1995, pp. 32-47

- Nabokov, Vladimir (1955). Lolita. New York: Vintage International. ISBN 0-679-72316-1.

- The original novel.

- "Zembla"

- A resource of the Arts & Humanities Library of the Pennsylvania State University Libraries, home of the International Vladimir Nabokov Society and its publication The Nabokovian.

See also

External links

- NPR: 50 Years Later, Lolita Still Seduces Readers

- Slate (magazine): Lolita at 50 - Is Nabokov's masterpiece still shocking?

- ^ http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1578073,00.html

- ^ http://www.randomhouse.com/features/nabokov/speak.html

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2087-1774602,00.html

- ^ http://www.onthemedia.org/transcripts/transcripts_091605_lolita.html

- ^ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1850954