Serer people: Difference between revisions

revert unexplained edit war, you will be reported next time, including for civility |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{overly detailed|date=November 2011}} |

{{overly detailed|date=November 2011}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | | footer = Kings of [[Kingdom of Sine|Sine]] Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof and Kumba Ndoffene Fandeb Joof<ref>Image footnote: The first image is a portrait of Maat Sine (King of Sine) Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof who reigned from 1840 to 1853. He was from the Royal House of Semou Njekeh Joof ("Mbind" or "Kerr" Semou Njekeh Joof). He is one of few precolonial [[Senegambian]] kings that became immortalised. This portrait was taken by L'abbé David Boillat in 1850 (three years before the death of the King). The second picture is of Maat Sine Kumba Ndoffene Fa Ndeb Joof who reigned from 1897 to 1924. He was from the Royal House of Boury Gnilane Joof ("Mbind" or "Kerr" Boury Gnilane Joof).</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

|||

{{Ethnic group |

{{Ethnic group |

||

|group=The Serer People |

|group=The Serer People |

||

|image = [[File:FemmeSérère.jpg|thumb]] |

|||

|poptime=Over 1.8 million<ref name="ReferenceA">Agence Nationale de Statistique et de la Démographie. Estimated figures for 2007 in Senegal alone</ref> |

|poptime=Over 1.8 million<ref name="ReferenceA">Agence Nationale de Statistique et de la Démographie. Estimated figures for 2007 in Senegal alone</ref> |

||

|popplace={{flagcountry|Senegal}} (1,840,712.1), |

|popplace={{flagcountry|Senegal}} (1,840,712.1), |

||

| Line 35: | Line 29: | ||

==History of the Serer people== |

==History of the Serer people== |

||

=== Ancient History === |

=== Ancient History === |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | | footer = Kings of [[Kingdom of Sine|Sine]] Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof and Kumba Ndoffene Fandeb Joof<ref>Image footnote: The first image is a portrait of Maat Sine (King of Sine) Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof who reigned from 1840 to 1853. He was from the Royal House of Semou Njekeh Joof ("Mbind" or "Kerr" Semou Njekeh Joof). He is one of few precolonial [[Senegambian]] kings that became immortalised. This portrait was taken by L'abbé David Boillat in 1850 (three years before the death of the King). The second picture is of Maat Sine Kumba Ndoffene Fa Ndeb Joof who reigned from 1897 to 1924. He was from the Royal House of Boury Gnilane Joof ("Mbind" or "Kerr" Boury Gnilane Joof).</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

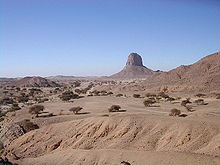

*Top to bottom: The first image of the [[Senegambian stone circles]] ([[megaliths]]) which runs from [[Senegal]] all the way to [[The Gambia]] and described by [[UNESCO]] as ''"the largest concentration of stone circles seen anywhere in the world."'' The site itself is believed to be an ancient burial site. The second image is in (modern day [[Mauritania]]) see [[West Saharan montane xeric woodlands]]. The third image is [[rock art]] in modern day Mauritania. For all image references including the [[Tassili n'Ajjer|Tasili]], see: Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. pp, 9, 20 & 77. ISBN 2-7236-1055-1 |

*Top to bottom: The first image of the [[Senegambian stone circles]] ([[megaliths]]) which runs from [[Senegal]] all the way to [[The Gambia]] and described by [[UNESCO]] as ''"the largest concentration of stone circles seen anywhere in the world."'' The site itself is believed to be an ancient burial site. The second image is in (modern day [[Mauritania]]) see [[West Saharan montane xeric woodlands]]. The third image is [[rock art]] in modern day Mauritania. For all image references including the [[Tassili n'Ajjer|Tasili]], see: Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. pp, 9, 20 & 77. ISBN 2-7236-1055-1 |

||

Revision as of 08:58, 18 November 2011

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (November 2011) |

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| |

| Languages | |

| Serer proper, Cangin languages, Wolof French (Senegal and Mauritania), English (The Gambia), | |

| Religion | |

| Serer Religion, some practice Christianity and Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Wolof people, Toucouleur people and Lebou people |

The Serer people (also spelt "Sérère", "Sereer", "Serere", "Seereer" and sometimes wrongly "Serre") along with the Jola people are acknowledged to be the oldest inhabitants of The Senegambia.[2]

In modern day Senegal, the Serer people live in the west-central part of the country, running from the southern edge of Dakar to The Gambian border.The Serer-Sine (also known as "Seex" or "Sine-Sine") occupy the ancient Sine and Saloum areas (now part of modern day independent Senegal). In The Gambia, they occupy parts of old "Nuimi" and "Baddibu" as well as The Gambian "Kombo". The Serer-Noon occupy the ancient area of Thiès in modern day Senegal. The Serer-Ndut are found in southern Cayor and north west of ancient Thiès. The Serer-Njeghen occupy old Baol; the Serer-Palor occupies the west central, west southwest of Thiès and the Serer-Laalaa occupy west central, north of Thiès and the Tambacounda area.[3][4]

The Serer people are the third largest ethnic group in Senegal making up 14.7% of the Senegalese population.[5] In Gambia they make up less than 2% of the population.[6] Along with Senegal and The Gambia, they are also found in small numbers in southern Mauritania. Some notable Gambian Serers include Isatou Njie-Saidy, Vice President of The Gambia since 20 March 1997, and the late Senegambian historian, politician and advocate for Gambia's independence during the colonial era - Alhaji Alieu Ebrima Cham Joof. In Senegal they include Leopold Sedar Senghor and Abdou Diouf (first and second president of Senegal respectively).

Serer subgroups

The Serer people include the Serer-Sine, Serer-Noon (sometimes spelt "Serer-None" or "Serer-Non"), Serer-Ndut (also spelt "N’doute"), Serer-Njeghene (sometimes spelt "Serer-Dyegueme" or "Serer-Gyegem" or "Serer-N'Diéghem"), Serer-Safene (speakers of the Saafi dialect of the Serer language), Serer-Niominka, Serer-Palor (also known as "Falor", "Palar", "Siili", "Siili-Mantine", "Siili-Siili", "Waro" or just "Serer"), and the Serer-Laalaa (sometimes known as "Laa", "La" or "Lâ" or just "Serer"). Each group speaks Serer-Sine or a different Cangin language. "Serer" is the standard English spelling. "Seereer" or "Sereer" reflects the actual pronunciation of the name and are mostly used by Senegalese Serer historians or scholars.

Ethnonym

The name "Serer" which not only identifies the people but also their language, culture, tradition, etc. is deemed by many anthropologists, linguists and historians (some of whom include Issa Laye Thiaw, Cheikh Anta Diop and Henry Gravrand (Henri Gravrand) to be an ancient and sacred word just as the Serer language itself.[7]

History of the Serer people

Ancient History

Several material relics have been found in different Serer countries relating to their pre-historic and ancient history. Most of these are about the past origins of Serer families, villages and Serer Kingdoms. Some of these relics included gold, silver and metals.[10] [11] Laterite megaliths carved planted in circular structures with stones were also discovered in Serer countries.[10]

Medieval history to present

Serer people’s medieval history is partly characterised by resisting Islamization from the 11th century during the Almoravid movement (particularly the Serers of Takrur)[12] to the 19th century Marabout movement of Senegambia.[13] Although the old Serer paternal dynasties continued, the Wagadou maternal dynasty was replaced by the Guelowar maternal dynasty in the 14th century.[14] The Serers also had to deal with religious based anti-Serer sentiments in the modern times brought on by their actions in resisting Islamization over the centuries particularly from the 19th century.[15] After the Ghana Empire was sacked as certain kingdoms gained their independence, Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar, leader of the Almoravids tried to get deeper into Senegal in the heart of Serer country to launch jihad. In November 1087 of the Christian calendar, the Serer King Ama Gôdô Maat defeated Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar and he was killed by a poisoned arrow.[16] In the Serer tradition, Ama Gôdô Maat also known as Bur Haman, was a Serer king not a fugitive, "Maat" (or "Maad" also "Mad") is the title of the old Serer kings.[17][18][19][20][21]

The last Serer kings

The last kings of Sine and Saloum were Maat Sine Mahecor Joof (also spelt "Mahecor Diouf") and Maat Saloum Fode Ngui Joof (also spelt "Fodé N’Gouye Diouf") respectively. They both died in 1969. After their deaths, the Serer Kingdoms of Sine and Saloum were incorporated into independent Senegal which gained its independence from France in 1960. The Serer kingdoms of Sine and Saloum are two of few pre-colonial African Kingdoms whose royal dynasty survived up to the 20th.[22]

The Serer kingdoms

Serer kingdoms included the Kingdom of Sine and the Kingdom of Saloum. In addition to these twin Serer kingdoms, the Serers also ruled in the Wolof kingdoms such as Jolof, Waalo, Cayor and Baol. The Kingdom of Baol was originally an old Serer Kingdom ruled by the Serer paternal dynasties such as Joof, Njie etc. and the Wagadou maternal dynasty prior to the Battle of Danki in 1549.[23] The "Wolof Empire" (proper: Jolof Empire, Joloff Empire or Empire du Dyoloff - in French) although associated with the Wolof people, in reality it was never ruled by the Wolof. All the so called "Wolof Kingdoms" such as Jolof, Waalo, Cayor and Baol were in actual fact ruled by Serers, Bambaras or Black Moors. Although the population were predominantly Wolofs with the exception of Baol, the rulers of these Kingdoms were not. For example:

- The kings of Jolof have the paternal lineage Njie which is originally Serer. Previous to the "Njie" or "Ndiaye" paternal dynasty, Jolof was ruled by the Ngom and Jaw dynasties who are also Serer in origin and the Mengue (also spelt "Mbengue") dynasty who are Lebou in origin (a tribe that is usually associated with the Wolof but in reality distinct).[24][25]

- The kings of Waalo came from the Mboge paternal lineage. The surname "Mbooj", "Mboge" or "Mbodj" derives from "Bo" which is Bambara in origin. The surname became Wolofized into "Mbooj" or "Mboge" just as the Fula surname "Bâ" or "Bah" became Wolofized into Mbacké. The three matrilineal dynasties of Waalo: "Joos" (also spelt "Dyoos" or "Djeuss"), "Tedyek" (also spelt "Teedyekk") and "Logar" (also spelt "Loggar") were not Wolofs. The Joos maternal dynasty trace their descend to a Serer princes called Linger Ndoye Demba from the Kingdom of Sine who was given in marriage to the king of Waalo in the 14th century. All the kings and princesses of Waalo with "Joos" maternal lineage were of Serer heritage. The "Tedyek" were Fula and the "Logar" were Moors.[26][27]

- The Faal paternal dynasty of Cayor and Baol that ruled after 1549 following the Battle of Danki were originally Black Moors. Prior to the Faal dynasty of Cayor and Baol, these two kingdoms were ruled by the Serer people with the patrilineages "Joof" or Diouf, Faye and Njie, and the maternal lineage of Wagadou – members of the royal families from the Ghana Empire (proper "Wagadou Empire") who married into the Serer aristocracy.[28]

At the time of the Jolof Empire, the Kingdom of Jolof was the administrative centre of the Emperor - from the Njie paternal dynasty who are Serers in origin. As such, although the term the "Wolof Empire" or "Jolof Empire" may indicate that it was the Wolof people who were ruling the Empire, in reality, it was ruled by the Serer people who became Wolofized by virtue of the fact that, these Serer kings resided in predominantly Wolof areas such as Jolof, etc. and became assimilated into Wolof culture.[29][30]

Social organization in the Serer kingdoms

The Serer Kings and land owners ( Maat, Maad or Laman or even "Barr" as used by some mainly non-Serers when referring to Serer kings) were at the top of the social strata. The terms "Buur Sine" and "Buur Saloum" (King of Sine and King of Saloum respectively) are Wolof terms when referring to Serer Kings. "Buur" or "Bur" are not Serer terms but Wolof terms.[31] When Serers refer to their kings they say "Maat" or "Mad" or "Maad". The Serer kings divided their capacity as follows (not in order of importance): the King of Sine "Maat Sine" or "Maat Saloum" appointed the chiefs of provinces named "Laman", of "Serer" or "Guelowar" origin (pre 1335 Lamans were not mere province Chiefs but kings, also the Guelowars became Serers and had Serer surnames).[32] All the kings that ruled Serer Kingdoms had Serer surnames with the exception of the Mboge and Faal paternal dynasties whose reigns are very recent and they did not provide many kings.[33] Nevertheless they had Serer mothers hence why they were able to rule in Saloum for instance. These post Turubang Lamans should not be confused with the ancient Lamans who were kings of their State as well as land owners, these recent Lamans were merely provincial chiefs answerable to the King of Sine or King of Saloum; the Farba Kaba (Chief of the Army); the Farba Binda (Minister of Finance also responsible for the police force and the Royal Palace), "Dialigne" or "Jaligne" (the Chief of the provinces inhabited by the Fula subjects); the Diaraf Beukeneg (Chief of the servants of the Royal Court) and the Serer "Jaraff" who headed the council of nobles some of whose main roles were to advise and elect the Serer Kings. Other notable titles included "Buumi" or "Bumi" (of Serer origin meaning inheritor). This word (Bumi) has been borrowed by the Wolof from the Serer but it is Serer in origin.[34] They were members of the Royal Family and were eligible to succeed after the death of Kings. The "Buur Kevel" or "Buur Geweel" (the Head Griot of the King). This person was also a rather important figure in the Royal Court as well as in wars. Not only did he kept the history and genealogy of the royal dynasty, he was also the advisor to the King. The "Buur Kevel(s)" or "Buur Geweel(s)" were very wealthy and powerful. They had the power to destroy a royal dynasty if they chose to do so. Their other role included accompanying kings to battles; advising kings when and how to launch a war against another kingdom; what the King should eat; how to walk; what to wear; whom to give audience to; whom to employ and whom to sack etc.[35]

Population

The Serer people are very diverse and though they spread throughout the Senegambia region, they are more numerous in places like old Baol, Sine, Saloum and in The Gambia which was a colony of the Kingdom of Saloum.

The following table gives the estimated Serer population per country:

| Country | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Senegal | 1,840,712.1[1] | ||

| The Gambia | 31,900[36] | ||

| Mauritania | 3500[37] | NB: The population count of the relevant countries especially in Senegal and The Gambia are controversial because there are some who believe populations are fixed to give other ethnicities numerical superiority such as the case of the Wolof people. Wolof people, Toucouleur people and Lebou people all trace their descend to Serer people and are therefore not an independent ethnic group particularly the Wolof. Yet the Wolof are seen as the largest ethnic group in Senegal and third largest in The Gambia. In fact, The Gambian authorities do not even know how many Serer people actually live there. Further, other ethnic groups who have assimilated with the Wolof are counted as Wolof when in fact they are not. Certain organisations especially in Senegal are pushing this phenomenon generally referred to as Wolofization.[38][39][40][41] |

Serer languages

Most people who identify themselves as Serer speak the Serer language. This is spoken in Sine-Saloum, Kaolack, Diourbel, Dakar, and in Gambia, and is part of the national curriculum of Senegal.

About 200,000 Serer speak various Cangin languages, such as Serer-Ndut and Serer-Safene, which are not closely related to Serer proper. There are clear lexical similarities among the Cangin languages. However, they are more closely related to other languages than to Serer, and vice versa.[42] For comparison in the table below, 85% is approximately the dividing line between dialects and different languages.

| Cangin languages and Serer-Sine | % Similarity with Serer-Sine | % Similarity with Serer-Noon | % Similarity with Saafi-Saafi (Serer-Safene) | % Similarity with Serer-Ndut | % Similarity with Serer-Palor | % Similarity with Serer-Laalaa (Serer-Lehar) | Areas they are predominantly found | Estimated population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serer-Laalaa (Serer-Lehar) | 22 | 84 | 74 | 68 | 68 | N/A | West central, north of Thies, Pambal area, Mbaraglov, Dougnan; Tambacounda area. Also found in The Gambia | 12,000 (Senegal figures only (2007) | |

| Serer-Ndut | 22 | 68 | 68 | N/A | 84 | 68 | West central, northwest of Thiès | 38,600 (Senegal figures only (2007) | |

| Serer-Noon | 22 | N/A | 74 | 68 | 68 | 84 | Thiès area. | 32,900 (Senegal figures only (2007) | |

| Serer-Palor | 22 | 68 | 74 | 84 | N/A | 68 | West central, west southwest of Thiès | 10,700 (Senegal figures only (2007) | |

| Saafi-Saafi | 22 | 74 | N/A | 68 | 74 | 74 | Triangle southwest of and near Thiès (between Diamniadio, Popenguine, and Thiès) | 114,000 (Senegal figures only (2007) | |

| Serer-Sine (Not a Cangin Language) | N/A | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | West central; Sine and Saloum River valleys. Also in The Gambia and small number in Mauritania | 1,154,760 (Senegal - 2006 figures); 31,900 (The Gambia - 2006 figures) and 3,500 (Mauritania 2006 figures)[43] | |

Serer culture

The Serer's favourite food is called Chere (also "Chereh" etc.) in the Serer language - (pounded coos). They control all the phases of this dish from production to preparation. Other ethnic groups (or Serers), tend to buy it from Serer women market traders or contract it out to them especially if they are holding major ceremonial events. Chere is very versertile and can be eaten with fermented milk or cream and sugar as a breakfast cereal or prepared just as a standard couscous. The Serer traditional attire is called Serr. It is normally woven by Serer men and believed to bring good luck among those who wear it. Marriages are usually arranged. In the event of the death of an elder, the sacred "Gamba" (a big calabash with a small hollow-out) is beaten followed by the usual funeral regalia to send them off to the next life.[44]

Wrestling

Senegalese wrestling called "Laamb" in Serer originated from the Serer Kingdom of Sine.[45] It was a preparatory exercise for war among the warrior classes. That style of wrestling (a brutal and violent form) is totally different from the sport wrestling enjoyed by all Senegambian ethnic groups today, nevertheless the ancient rituals are still visible in the sport version. Among the Serers, wrestling is classifed into different techniques and each technique takes several years to master. Children start young trying to master the basics before moving on to the more advance techniques like the "mbapatte", which is one of the oldest tehniques and totally different from modern wrestling. Yékini (real name: "Yakhya Diop"), who is a professional wrestler in Senegal is one of the top wrestlers proficient in the "mbapatte" technique. Lamba and sabar (musical instruments) are used as music ccompaniments in wrestling matches as well as in circumcision dances and royal festivals.[46] Serer wrestling crosses ethnic boundaries and is a favourite pastime for Senegalese and Gambians alike.

Music

The Sabar (drum) tradition associated with the Wolof people originated from the Serer Kingdom of Sine and spread to the Kingdom of Saloum. The Wolof people who migrated to Serer Saloum picked it up from there and spread it to Wolof Kingdoms.[47] Each motif has a purpose and are used for different occasions. For example the musical motifs representing the family history and genealogy of a particular family; weddings; naming ceremonies; funerals etc.

The "Tassu" tradition (also "Tassou") which is the progenitor of rap originated from the Serer people. It was used when chanting ancient religious verses. The people would sing then interweave it with a "Tassu". The late Serer Diva Yandé Codou Sène who was the griot of the late and former president of Senegal (Leopold Sedar Senghor) was proficient in the "Tassu". She was the best "Tassukat" (one who Tassu) of her generation. Originally religious in nature, the griots of Senegambia regardless of ethnic group or religion picked it up from Serer religious practices and still use it in different occasions e.g. marriages, naming ceremonies or when they are just singing the praises of their patrons. Most Senegalese and Gambian artists use it in their songs even the younger generation like "Baay Bia". The Senegalese music legend Youssou N'Dour who is also a Serer, uses "Tassu" in many of his songs.[48] As noted by Ali Colleen Neff:

- "The Serer people are known especially for their rich knowledge of vocal and rhythmic practices that infuse their everyday language with complex overlapping cadences and their ritual with intense collaborative layerings of voice and rhythm."[48]

Occupation

The Serers practice trade, agriculture, fishing, boat building and animal husbandry. The majority of Serers are farmers and/or land owners since unmemorable times. Although they practice animal husbandry, they are generallly less known for that, as in the past, Serer nobles entrusted their herds to the pastoralist Fulas. Even nowadays some Serers do that. Trade is also a recent phenomenon among many Serers. For the Serers, the soil (where their ancestors lay in rest) is very important to them and they guard it with jealousy. They have a legal framework governing every aspect of life even land law with strict guidelines. Apart from agriculture (and other forms of production or occupation such as animal husbandry, fishing especially among the Serer-Niominka, boat building, etc.), some occupations especially trade they viewed as vulgar, common and ignoble. This is why in the colonial era especially among the Serer nobles, they would hire others to do the trading on their behalf - acting as middle men, usually the Moors from Mauritania whom to this day they do not trust and are prejudice towards. In the pre-colonial times, Moors from Mauritania who came to settle in the Serer Kingdoms were ill treated by their Serer masters if that is they were even welcomed and allowed to stay. If a Moor dies in a village or principality for instance, his body was dragged out of the village and left for the vultures to feast on if there is no family or friend to claim the body and bury it elsewhere and not in the Serer Kingdoms. They were also never accompanied by grave goods. No matter how long a Mauritanian Moor has lived in the area as a migrant, he could never achieve high status within the Serer aristocracy. The best position he could ever wish for within Serer high society was to work as a Bissit (Bissik). Apart from spying for the Serer Kings, the Bissit's main job was to be a clown - for the sole entertainment of the Serer King, the Serer aristocracy and the common people. He was expected to dance in ceremonies before the king and liven up the king's mood and the king's subjects. This position was always given to the Moors and that was the highest position they could wish for. It was a humiliating job and not a title of honour. The purpose of this position was solely created to humiliate the Moors whom the Serers at that time (even now to some degree) view as "dishonourable and shameful". The history of this position in the Serer Kingdoms is said to have gone back to an early Moor in the area who had a son by his own daughter. This is why that position was especially given to any Moor that wished to fill the vacant position.[49] The Serer people’s unwillingness to trade (in mass numbers) directly during the colonial era was a double edged sword to the Serer language as well as the Cangin languages. That resulted in the Wolof language being the dominant language in the market place as well as the factories. As such, the Wolof language became dominant after the colonials left.[50] However, the Serer language among with other local languages are now part of the national curriculum of Senegal.

Joking relationship (Kal)

Serers and Toucouleurs are linked by a bond of "cousinage". This is a tradition common to many ethnic groups of West Africa called a "Relation du jeste" (Joking relationship) - known as "kal" in Serer, which comes from "kalcular" - meaning paternal lineage (a deformation of the Serer word "kucarla"). This joking relationship enables one group to criticise another, but also obliges the other with mutual aid and respect. The Serers call this "Kal". This is because the Serers are the ancestors of the Toucouleurs.[51] The Serers also maintain the same bond with the Jola people with whom they have an ancient relationship.[52] In the Serer ethnic group, this same bond exists between the Serer patronym, for example between Joof and Faye.

All Senegambian people also refer to this joking relations as "kal" (used between first cousins for example between the children of a paternal aunt and a maternal uncle) and "gamo" (used between tribes). Again, these words are borrowed from the Serer language.[53] The word "gamo" derives from the old Serer word "gamohu" or "gamohou" (also "gamahou" - an ancient divination ceremony)[54][55]

Serer cultural, religious, musical traditions and terminology have had a strong imprint on Senegambia. Even the ancient religious ceremonies of the Serer people which are animistic in nature have made their mark on Senegambian people and are borrowed by Senegambian Muslims to describe their Islamic ceremonies.[56]

Serer patronyms

| Some of the common Serer surnames |

|---|

Religion

Practitioners of the Serer religion believe in a universal Supreme Deity called Rog also spelt Roog and sometimes referred to as Rog Sene (Rog the Immensity). They have an elaborate religious tradition dealing with various dimensions of life, death, space and time, ancestral spirit communications and cosmology. Until the colonial period, the Serer people resisted both Islamization and Wolofization. They saw Islamization as an aspect of Wolofization.[57][58] However, some note that many Serers still follow their traditional religious beliefs.[59][60]

Sport

The sport played by the Serer is the wrestling called "Laamb". In ancient times, this was not merely a sport, but a preparation for war. The "battle wrestling" and the "sport wrestling" of today are totally different. However if one looks closely at the ritual dances of pre-wrestling Serer sport, one will see elements of battle. The Serers have a long history of being renowned warriors.[61] Wrestling, the preparatory exercises for war, therefore holds great significance among the Serers. The "Laamb" is now a cultural pastime for all Senegambian people crossing religion and ethic boundaries.

See also

Related ethnic groups and dialect

Other ethnic groups

Serer kingdoms

History

Senegal

- Demographics of Senegal

- List of Presidents of Senegal (Senegal had three presidents after independence. Both the first and second were Serers).

Royalty

- Lamane (An ancient title).

- Ama Gôdô Maat - (the 11th century Serer king who defeated the Almoravid leader Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar).

- Maat Sine Kumba Ndoffene Famak Joof - (King of Sine 1853 - 1871)

- Coronation of Kumba Ndoffene Famak Joof

Filmography

- Template:Fr "Molaan" - A documentary film by Moussa Sene Absa, audiovisual ORSTOM, Bondy, 1994, 25 '(VHS)

- Template:Fr "Le Mbissa" - A documentary film by Alexis Fifis and Cécile Walter, produced by the IRD [2]

Notes

- ^ a b Agence Nationale de Statistique et de la Démographie. Estimated figures for 2007 in Senegal alone

- ^ Gambian Studies No. 17. People of The Gambia. I. The Wolof by David P. Gamble & Linda K. Salmon with Alhaji Hassan Njie. San Francisco 1985.

- ^ Patience Sonko-Godwin. Ethnic Groups of The Senegambia Region. A Brief History. p32. Sunrise Publishers Ltd. Third Edition, 2003. ISBN 9983 990062

- ^ Ethnologue.com. Languages of Senegal. 2007 figures

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sg.html CIA Factsheet

- ^ [1] Ethnologue.com

- ^ "La Religiosité des Sereer, avant et pendant leur Islamisation". Éthiopiques, No: 54, Revue Semestrielle de Culture Négro-Africaine. Nouvelle Série, Volume 7, 2e Semestre 1991. By Issa Laye Thiaw

- ^ Image footnote: The first image is a portrait of Maat Sine (King of Sine) Ama Joof Gnilane Faye Joof who reigned from 1840 to 1853. He was from the Royal House of Semou Njekeh Joof ("Mbind" or "Kerr" Semou Njekeh Joof). He is one of few precolonial Senegambian kings that became immortalised. This portrait was taken by L'abbé David Boillat in 1850 (three years before the death of the King). The second picture is of Maat Sine Kumba Ndoffene Fa Ndeb Joof who reigned from 1897 to 1924. He was from the Royal House of Boury Gnilane Joof ("Mbind" or "Kerr" Boury Gnilane Joof).

- ^ a b c Gravrand, Henry: " La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. pp, 9, 20 & 77. ISBN 2-7236-1055-1."

- Top to bottom: The first image of the Senegambian stone circles (megaliths) which runs from Senegal all the way to The Gambia and described by UNESCO as "the largest concentration of stone circles seen anywhere in the world." The site itself is believed to be an ancient burial site. The second image is in (modern day Mauritania) see West Saharan montane xeric woodlands. The third image is rock art in modern day Mauritania. For all image references including the Tasili, see: Henry Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool. Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. pp, 9, 20 & 77. ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- Becker, Charles: "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer". Dakar. 1993. CNRS - ORS TO M

- ^ a b Becker, Charles: "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer". Dakar. 1993. CNRS - ORS TO M"

- ^ Charles Becker et Victor Martin, Rites de sépultures préislamiques au Sénégal et vestiges protohistoriques, Archives Suisses d'Anthropologie Générale, Imprimerie du Journal de Genève, Genève, 1982, tome 46, N° 2, p. 261-293

- ^ See Godfrey Mwakikagile. Also see:

- Martin A. Klein. Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847-1914, Edinburgh At the University Press (1968)

- ^ See Martin Klein p62-93

- ^ For old paternal Serer dynasties such as Joof or Diouf, etc and the maternal dynasty of Wagadou, see: Andrew F. Clark and Lucie Colvin Philips. Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Second Edition (1994). For the Guelowars, see Alioune Sarr' Histoire du Sine Saloum.

- ^ Senegal

- ^

- Henri Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer. Cosaan : les origines, p118. Dakar, Nouvelles Editions Africaines (1983)

- Henry Gravrand,La civilisation Sereer, Pangool, p13. Dakar, Nouvelles Editions Africaines (1990)

- Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire. Bulletin, Volumes 26-27. Published by IFAN (1964)

- Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire. Mémoires de l'Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire, Issue 91, Part 2. Published by IFAN (1980)

- Marcel Mahawa Diouf. Lances mâles: Léopold Sédar Senghor et les traditions Sérères, p54. Published by: Centre d'études linguistiques et historiques par tradition orale (1996)

- Patience Sonko-Godwin. Ethnic groups of the Senegambia: a brief history. Published by Sunrise Publishers. 1988. ISBN 9983860007

- J. F. P. Hopkins, Nehemia Levtzion. Corpus of early Arabic sources for West African history, p-p247-8. Markus Wiener Publishers (2000)

- Ronald A. Messier. "The Almoravids and the meanings of jihad", p86. Published by ABC-CLIO (2010). ISBN 0313385890

- ^ Roland Oliver, John Donnelly Fage, G. N. Sanderson. The Cambridge History of Africa, p214. Cambridge University Press, 1985. ISBN 0521228034

- ^ Dawda Faal. Peoples and empires of Senegambia: Senegambia in history, AD 1000-1900, p17. Published by Saul's Modern Printshop (1991)

- ^ J. F. Ade Ajayi and Michael Crowder. History of West Africa, Volume 1, p 468. Published by: Longman, 1985. ISBN 0582646839

- ^ Dennis C. Galvan. The State Must be Our Master of Fire, p270. Published by University of California Press (2004). ISBN 9780520235915

- ^ Marcel Mahawa Diouf. Lances mâles: Léopold Sédar Senghor et les traditions Sérères, p54. Published by: Centre d'études linguistiques et historiques par tradition orale (1996)

- ^ See Sarr; Bâ, also: Klein: Rulers of Sine and Saloum, 1825 to present (1969).

- ^ Lucie Gallistel Colvin. Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Scarecrow Press/ Metuchen. NJ - London (1981) ISBN 081081885x

- ^ Le Djoloff et ses bourba(French) by Oumar Ndiaye Leyti.

- ^ Samba Diop. The Wolof Epic: From Spoken Word to Written Text. "The Epic of Ndiadiane Ndiaye

- ^ Amadou Wade. Chronique du Wâlo Sénégalais, 1186?-1855. Published and commented on by Vincent Monteil . Bulletin de l'IFAN, 1964, tome 26, no 3-4.

- ^ Boubacar Barry. Le Royaume Du Waalo: Le Senegal Avant La Conquête., p72-75. ISBN 2865371417 (2-86537-141-7)

- ^ Andrew F. Clark and Lucie Colvin Philips. Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Second Edition (1994).

- ^ Donal Cruise O'Brien. Langues et nationalité au Sénégal. L'enjeu politique de la Wolofisation. Année Africaine, Pédone. 1979.

- ^ Two studies on ethnic group relations in Africa - Senegal, The United Republic of Tanzania. Pages 14-15. UNESCO. 1974

- ^ Note: Although the word "Buur" is Serer in origin it it is normally attributed to the Wolof who tend to use it to describe their Kings. There are thousands of Serer words found in the Wolof language. The Wolof have a great ability to absorb from other culture and make it their own. See Taal.

- ^ For more on Geulowars see Alioune Sarr. Also see the Medieval history of the Serer people.

- ^ For the list of Kings see Klein; Sarr and Gravrand's "La civilisation Sereer Cosaan".

- ^ See Klein p14-15

- ^ For Serer Social organisations see: Henri Gravrand. La Civilisation Sereer, Cosaan - Origine. Also see:

- Martin A. Klein. Islam and Imperialism in Senegal, p12-15

- ^ The Gambia does not keep good record of its ethnic minorities. Estimated figure for (2006).Ethnologue.com

- ^ Mauritania does not keep good records. Etimated figures (2006) Joshua Project

- ^ Ebou Momar Taal. "Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability". 2010

- ^ Cheikh Anta Diop. Nations nègres et culture: de l'antiquité nègre égyptienne aux problèmes culturels de l'Afrique noire d'aujourd'hui. 1954

- ^ Makhtar Diouf. Sénégal, les ethnies et la nation. Nouvelles Éditions Africaines du Sénégal. Dakar. (1998).

- ^ African Sensus Analysis Project (ACAP). University of Pensylvania. Ethnic Diversity and Assimilation in Senegal: Evidence from the 1988 Census by Pieere Ngom, Aliou Gaye and Ibrahima Sarr. 2000

- ^ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. (Ethnologue.com - 2006 and 2007).

- ^ NB: 2006 Figures are taken in order to compare the population of the Serer-Sine in the respective countries.

- ^ Godfrey Mwakikagile. The Gambia and Its People: Ethnic Identities and Cultural Integration in Africa, p141. ISBN 9987160239

- ^ Patricia Tang. Masters of the sabar: Wolof griot percussionists of Senegal, p144. Temple University Press, 2007. ISBN 1592134203

- ^ David P. Gamble. The Wolof of Senegambia: together with notes on the Lebu and the Serer, p77. International African Institute, 1957

- ^ Patricia Tang. Masters of the sabar: Wolof griot percussionists of Senegal, p-p32, 34. Temple University Press, 2007. ISBN 1592134203

- ^ a b Ali Colleen Neff. Tassou: the Ancient Spoken Word of African Women. 2010.

- ^ Abdou Bouri Bâ. Essai sur l’histoire du Saloum et du Rip. Avant-propos par Charles Becker et Victor Martin, p4

- ^ Martin A, Klein, p7

- ^ According to both the Toucouleur and Serer tradition and backed up by several sources one of which include: William J. Foltz. From French West Africa to the Mali Federation, Volume 12 of Yale studies in political science, p136. Published by Yale University Press, 1965.

- ^ According to both Serer and Jola tradition, they trace their descend to Jambonge and Ougeney (also spelt "Eugeny). For more on this see Ebou Momar Taal, Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability. 2010

- ^ "Kal" derives from the Serer word "kurcala" which means paternal lineage or inheritance and is used exactly in that context by all Senegambians. "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer". Dakar. 1993. Charles BECKER, CNRS - ORS TO M

- ^ IFAN. Ethiopiques numéro 31 révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine 3e trimestre 1982 . By Mor Sadio Niang.

- ^ Niokhobaye Diouf. Chronique du royaume du Sine par suivie de notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin.

- ^ (see Serer religion: Serer Religious Festivals: There influence on Senegambia)

- ^ Sufism and jihad in modern Senegal: the Murid order By John Glover

- ^ Conversion to Islam: Military Recruitment and Generational Conflict in a Sereer-Safin Village (Bandia)

- ^ See Godfrey Mwakikagile. The Gambia and its People: Ethnic Identities and cultural integration in Africa, p133

- ^ Elizabeth L Berg, Ruth Wan. Senegal. Cultures of the World. Volume 17, p63. 2nd Edition. Published by: Marshall Cavendish, 2009. ISBN 0761444815

- ^ Elisa Daggs. All Africa: All its political entities of independent or other status. Hasting House, 1970. ISBN 0803803362, 9780803803367

Bibliography

- Mamadou Diouf & Mara Leichtman, New perspectives on Islam in Senegal: conversion, migration, wealth, power, and femininity. Published by: Palgrave Macmillan. 2009. the University of Michigan. ISBN 0230606482, 9780230606487

- Mamadou Diouf, History of Senegal: Islamo-Wolof model and its outskirts. Maisonneuve & Larose. 2001. ISBN 2706815035, 9782706815034

- David P. Gamble & Linda K. Salmon with Alhaji Hassan Njie, Gambian Studies No. 17. People of The Gambia. I. The Wolof San Francisco 1985.

- Ebou Momar Taal, Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability. 2010

- Elizabeth L. Berg and Ruth Wan. "Senegal". Cavendish Marshall. 2009.

- Alvise Cadamosto, Kerr (originally Portuguese) - (English commentaries - Verrier. 1994: p. 136. Russell. 2000: p. 299-300).

- Florence Mahoney, Stories of Senegambia. Publisher by Government Printer, 1982

- Elisa Daggs. All Africa: All its political entities of independent or other status. Hasting House, 1970. ISBN 0803803362, 9780803803367

- Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hilburn Timeline of Art History. The Fulani/Fulbe People.

- Russell G. Schuh, The Use and Misuse of language in the study of African history. 1997

- Andrew Burke and David Else, The Gambia & Senegal, 2nd edition - September 2002. Published by Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd, page 13

- Daniel Don Nanjira, African Foreign Policy and Diplomacy: From Antiquity to the 21st Century. Page 91-92. Published by ABC-CLIO. 2010. ISBN 0313379823, 9780313379826

- Maurice Lombard, The golden age of Islam. Page 84. Markus Wiener Publishers. 2003. ISBN 1558763228, 9781558763227

- Roland Anthony Oliver, & J. D. Fage, Journal of African History. Volume 10. Published by: Cambridge University Press. 1969

- The African archaeological review, Volumes 17-18. Published by: Plenum Press, 2000

- J. F. Ade Ajayi & Michael Crowder, History of West Africa, Volume 1. Published by: Longman, 1985. ISBN 0582646839, 9780582646834

- Peter Malcolm Holt, The Indian Sub-continent, south-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim West. Volume 2, Part 1. Published by: Cambridge University Press. 1977. ISBN 0521291372, 9780521291378

- Molefi K. Asante, The history of Africa: the quest for eternal harmony. Routledge. 2007. ISBN 0415771390, 9780415771399

- Willie F. Page, Encyclopedia of African history and culture: African kingdoms (500 to 1500). Volume 2. Published by: Facts on File. 2001. ISBN 0816044724, 9780816044726

- Anthony Ham, West Africa. Published by: Lonely Planet. 2009. ISBN 1741048214, 9781741048216

- Godfrey Mwakikagile, Ethnic Diversity and Integration in the Gambia. Page 224

- François G. Richard, "Recharting Atlantic encounters. Object trajectories and histories of value in the Siin (Senegal) and Senegambia". Archaeological Dialogues 17 (1) 1–27. Cambridge University Press 2010

- Samba Diop, The Wolof Epic: From Spoken Word to Written Text. "The Epic of Ndiadiane Ndiaye"

- Two studies on ethnic group relations in Africa - Senegal, The United Republic of Tanzania. Pages 14–15. UNESCO. 1974

- Dennis Charles Galvan, The State Must Be Our Master of Fire: How Peasants Craft Culturally Sustainable Development in Senegal. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2004

- Martin A. Klein, Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847–1914, Edinburgh At the University Press (1968)

- Lucie Gallistel Colvin. Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Scarecrow Press/ Metuchen. NJ - London (1981) ISBN 081081885x

- Portions of this article were translated from the French language Wikipedia article fr:Sérères, 2008-07-08 and August 2011.

- Patience Sonko Godwin. Leaders of Senegambia Region, Reactions To European Infiltration 19th-20th Century. Sunrise Publishers Ltd - The Gambia (1995) ISBN 9983860023

- Patience Sonko Godwin. Ethnic Groups of The Senegambia Region, A Brief History. Third Edition. Sunrise Publishers Ltd - The Gambia (2003). ISBN 9983990062

- Dennis C. Galvan. The State Must be Our Master of Fire. ISBN 9780520235915

- Samba Diop. The Wolof Epic: From Spoken Word to Written Text. "The Epic of Ndiadiane Ndiaye"

- Andrew F. Clark and Lucie Colvin Philips. Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Second Edition (1994)

External links

External links

- Moving from Teaching African Customary Laws to Teaching African Indigenous Law. By Dr Fatou. K. Camara [PDF]

- Ethnolyrical. Tassou: The Ancient Spoken Word of African Women