Widow: Difference between revisions

Squatch347 (talk | contribs) Undid revision 1033520041 by Orientls (talk) Multiple issues with edit. Editor unnecessarily broadens geographical references (which aren't supported in sources). Removes references to significant legal changes. Changes timeline of practice to be out of context from source, and strips specific references to groups made in sources. |

Replace with a working source |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

While it is disputed as to whether sex plays a part in the intensity of grief, sex often influences how an individual's lifestyle changes after a spouse's death. Research has shown that the difference falls in the burden of care, expectations, and how they react after the spouse's death. For example, women often carry more of an emotional burden than men and are less willing to go through the death of another spouse.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=http://go.galegroup.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA380342155|title=The effect of widowhood on husbands' and wives' physical activity: the cardiovascular health study|via=[[Gale Academic OneFile]]|access-date=2016-04-28|journal=Journal of Behavioral Medicine|volume=37 |issue=4|pages=806–817|last1=Stahl|first1=Sarah T.|last2=Schulz|first2=Richard|doi=10.1007/s10865-013-9532-7|pmid=23975417|pmc=3932151|year=2014}}</ref> After being widowed, however, men and women can react very differently and frequently have a change in lifestyle. Women tend to miss their husbands more if he died suddenly; men, on the other hand, tend to miss their wives more if she died after suffering a long, terminal illness.<ref name="Wilcox 2003">{{Cite journal|doi=10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513|pmid=14570535|title=The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women's Health Initiative|journal=Health Psychology|volume=22|issue=5|pages=513–22|year=2003|last1=Wilcox|first1=Sara|last2=Evenson|first2=Kelly R.|last3=Aragaki|first3=Aaron|last4=Wassertheil-Smoller|first4=Sylvia|author-link4=Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller|last5=Mouton|first5=Charles P.|last6=Loevinger|first6=Barbara Lee}}</ref> In addition, both men and women have been observed to experience lifestyle habit changes after the death of a spouse. Both sexes tend to have a harder time looking after themselves without their spouse to help, though these changes may differ based on the sex of the widow and the role the spouse played in their life.<ref name="Wilcox 2003"/> |

While it is disputed as to whether sex plays a part in the intensity of grief, sex often influences how an individual's lifestyle changes after a spouse's death. Research has shown that the difference falls in the burden of care, expectations, and how they react after the spouse's death. For example, women often carry more of an emotional burden than men and are less willing to go through the death of another spouse.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=http://go.galegroup.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA380342155|title=The effect of widowhood on husbands' and wives' physical activity: the cardiovascular health study|via=[[Gale Academic OneFile]]|access-date=2016-04-28|journal=Journal of Behavioral Medicine|volume=37 |issue=4|pages=806–817|last1=Stahl|first1=Sarah T.|last2=Schulz|first2=Richard|doi=10.1007/s10865-013-9532-7|pmid=23975417|pmc=3932151|year=2014}}</ref> After being widowed, however, men and women can react very differently and frequently have a change in lifestyle. Women tend to miss their husbands more if he died suddenly; men, on the other hand, tend to miss their wives more if she died after suffering a long, terminal illness.<ref name="Wilcox 2003">{{Cite journal|doi=10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513|pmid=14570535|title=The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women's Health Initiative|journal=Health Psychology|volume=22|issue=5|pages=513–22|year=2003|last1=Wilcox|first1=Sara|last2=Evenson|first2=Kelly R.|last3=Aragaki|first3=Aaron|last4=Wassertheil-Smoller|first4=Sylvia|author-link4=Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller|last5=Mouton|first5=Charles P.|last6=Loevinger|first6=Barbara Lee}}</ref> In addition, both men and women have been observed to experience lifestyle habit changes after the death of a spouse. Both sexes tend to have a harder time looking after themselves without their spouse to help, though these changes may differ based on the sex of the widow and the role the spouse played in their life.<ref name="Wilcox 2003"/> |

||

The older spouses grow, the more aware they are of being alone due to the death of their husband or wife. This negatively impacts the mental as well as physical well-being in both men and women.<ref>Utz, Reidy, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, |

The older spouses grow, the more aware they are of being alone due to the death of their husband or wife. This negatively impacts the mental as well as physical well-being in both men and women.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/142738/Nesse-Carr-House_Perf-JFI-2004.pdf?sequence=1|title=The Daily Consequences of Widowhood|author= Utz, Reidy, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman,|year=2004}}</ref> |

||

== Mourning practices == |

== Mourning practices == |

||

In some parts of Europe, including Russia, [[Czechoslovakia]], [[Greece]], [[Italy]] and [[Spain]], widows used to wear black for the rest of their lives to signify their mourning, a practice that has since died out. However, [[Eastern Orthodox|Orthodox Christian]] immigrants may wear lifelong black in the United States to signify their widowhood and devotion to their deceased husband. |

In some parts of Europe, including Russia, [[Czechoslovakia]], [[Greece]], [[Italy]] and [[Spain]], widows used to wear black for the rest of their lives to signify their mourning, a practice that has since died out. However, [[Eastern Orthodox|Orthodox Christian]] immigrants may wear lifelong black in the United States to signify their widowhood and devotion to their deceased husband. |

||

The status of widowhood for Indians was accompanied by a body symbolism<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Many Colors of Hinduism|last=Olson|first=Carl|publisher=Rutgers University Press|page=269}}</ref> - The widow's head was shaved as part of her mourning, she could no longer wear a red dot (sindur) on her forehead and was forbidden to wear wedding jewellery and she was expected to walk barefoot. These customs are mostly considered backward now and have more or less disappeared.<ref>{{cite news |title=On India's back roads, sati revered |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-dec-10-adfg-widows10-story.html |work=Los Angeles Times |date=10 December 2006}}</ref> |

|||

Some people in [[South Asia]] consider a widow to have caused her husband's death and is not allowed to look at another person as her gaze is considered bad luck.<ref>{{cite book|title=Violence Against Women|quote=widows in South Asia are considered bad luck|author=Kathryn Roberts|page=62|publisher=Greenhaven Publishing LLC|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yRWDDwAAQBAJ}}</ref><ref name=pri>{{cite news|url=https://www.pri.org/stories/2018-10-23/these-kenyan-widows-are-fighting-against-sexual-cleansing|title=These Kenyan widows are fighting against sexual 'cleansing'|publisher=pri.org|access-date=7 November 2018|date=23 October 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Some Nigerians prefer widow to drink the water her dead husband’s body was washed in, or otherwise sleep next to her husband's grave for three days.<ref name=pri/> |

|||

In the [[Chilote mythology|folklore of Chiloé]] of southern Chile, widows and [[black cat]]s are important elements that are needed when hunting for the treasure of the [[carbunclo]].<ref name=Quintanaweb>{{Cite book|title=Chiloé mitológico|last=Quintana Mansilla|first=Bernardo|author-link=Bernardo Quintana|language=es|chapter=El Carbunco|year=1972|chapter-url=http://chiloemitologico.cl/los-mitos-de-chiloe/mitos-terrestres/el-carbunco}}</ref><ref name=Lwarence2015>{{Cite book|title=Stories of the Southern Sea|last=Winkler|first=Lawrence|publisher=First Choice Books|year=2015|isbn=978-0-9947663-8-0|pages=54}}</ref> |

In the [[Chilote mythology|folklore of Chiloé]] of southern Chile, widows and [[black cat]]s are important elements that are needed when hunting for the treasure of the [[carbunclo]].<ref name=Quintanaweb>{{Cite book|title=Chiloé mitológico|last=Quintana Mansilla|first=Bernardo|author-link=Bernardo Quintana|language=es|chapter=El Carbunco|year=1972|chapter-url=http://chiloemitologico.cl/los-mitos-de-chiloe/mitos-terrestres/el-carbunco}}</ref><ref name=Lwarence2015>{{Cite book|title=Stories of the Southern Sea|last=Winkler|first=Lawrence|publisher=First Choice Books|year=2015|isbn=978-0-9947663-8-0|pages=54}}</ref> |

||

| Line 36: | Line 38: | ||

It may be necessary for a woman to comply with the [[social custom]]s of her area because her fiscal stature depends on it, but this custom is also often abused by others as a way to keep money within the deceased spouse's family.<ref name="Imagine">"Imagine...." Widows' Rights International. Web. 14 Sep 2010. <http://www.widowsrights.org/index.htm>.</ref> It is also uncommon for widows to challenge their treatment because they are often "unaware of their rights under the modern law…because of their low status, and lack of education or legal representation.".<ref name="World of Widows">Owen, Margaret. ''A World of Widows''. Illustrated. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Zed Books, 1996. 181-183. eBook.</ref> Unequal benefits and treatment{{clarify|date=September 2016}} generally received by widows compared to those received by widowers globally{{examples|date=September 2016}} has spurred an interest in the issue by [[human rights activists]].<ref name="World of Widows" /> During the HIV pandemic, which particularly hit gay communities, companions of deceased men had little recourse in estate court against the deceased family. Not yet able to have been legally married the term widower was not considered socially acceptable. This situation was usually blessed with an added stigma being attached to the surviving man. |

It may be necessary for a woman to comply with the [[social custom]]s of her area because her fiscal stature depends on it, but this custom is also often abused by others as a way to keep money within the deceased spouse's family.<ref name="Imagine">"Imagine...." Widows' Rights International. Web. 14 Sep 2010. <http://www.widowsrights.org/index.htm>.</ref> It is also uncommon for widows to challenge their treatment because they are often "unaware of their rights under the modern law…because of their low status, and lack of education or legal representation.".<ref name="World of Widows">Owen, Margaret. ''A World of Widows''. Illustrated. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Zed Books, 1996. 181-183. eBook.</ref> Unequal benefits and treatment{{clarify|date=September 2016}} generally received by widows compared to those received by widowers globally{{examples|date=September 2016}} has spurred an interest in the issue by [[human rights activists]].<ref name="World of Widows" /> During the HIV pandemic, which particularly hit gay communities, companions of deceased men had little recourse in estate court against the deceased family. Not yet able to have been legally married the term widower was not considered socially acceptable. This situation was usually blessed with an added stigma being attached to the surviving man. |

||

As of 2004, women in United States who were "widowed at younger ages are at greatest risk for economic hardship." Similarly, married women who are in a financially unstable household are more likely to become widows "because of the strong relationship between mortality [of the male head] and wealth [of the household]."<ref name="Imagine" /> In underdeveloped and developing areas of the world, conditions for widows continue to be much more severe. However, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women ("now ratified by 135 countries"), while slow, is working on proposals which will make certain types of discrimination and treatment of widows (such as violence and withholding property rights) illegal in the countries that have joined CEDAW.<ref |

As of 2004, women in United States who were "widowed at younger ages are at greatest risk for economic hardship." Similarly, married women who are in a financially unstable household are more likely to become widows "because of the strong relationship between mortality [of the male head] and wealth [of the household]."<ref name="Imagine" /> In underdeveloped and developing areas of the world, conditions for widows continue to be much more severe. However, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women ("now ratified by 135 countries"), while slow, is working on proposals which will make certain types of discrimination and treatment of widows (such as violence and withholding property rights) illegal in the countries that have joined CEDAW.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v65n3/v65n3p31.html|title=The Economic Consequences of a Husband's Death: Evidence from the HRS and AHEAD|publisher=US Social Security Administration}}</ref> |

||

In the United States, Social Security offers a Survivor's Benefit to qualified individuals once for a loss through their 50th birthday after which a second marriage may be considered when applying for benefits. The maximum still remains the same but here the survivor has options between accessing their earned benefits or one of their qualifying late spouses at chosen intervals to maximize the increased benefits for delaying a filing (i.e. at age 63 claim husband one's reduced benefit, then husband two's full amount at 67 and your own enhanced benefit at 68). |

In the United States, Social Security offers a Survivor's Benefit to qualified individuals once for a loss through their 50th birthday after which a second marriage may be considered when applying for benefits. The maximum still remains the same but here the survivor has options between accessing their earned benefits or one of their qualifying late spouses at chosen intervals to maximize the increased benefits for delaying a filing (i.e. at age 63 claim husband one's reduced benefit, then husband two's full amount at 67 and your own enhanced benefit at 68). |

||

==Abuse of widows== |

==Abuse of widows== |

||

=== |

===Sexual violence=== |

||

{{See also|Sexual cleansing#Widow cleansing|l2=Widow cleansing}} |

{{See also|Sexual cleansing#Widow cleansing|l2=Widow cleansing}} |

||

In parts of Africa, such as [[Kenya]], widows are viewed as impure and need to be 'cleansed'. This often requires having sex with someone. Those refusing to be cleansed risk getting beaten by superstitious villagers, who may also harm the woman's children. It is argued that this notion arose from the idea that if a husband dies, the woman may have performed witchcraft against him. |

In parts of Africa, such as [[Kenya]], widows are viewed as impure and need to be 'cleansed'. This often requires having sex with someone. Those refusing to be cleansed risk getting beaten by superstitious villagers, who may also harm the woman's children. It is argued that this notion arose from the idea that if a husband dies, the woman may have performed witchcraft against him. |

||

Use of widows in [[harem]] has been recorded in [[Ancient Egypt]], medieval Europe, and Islamic empires.<ref name="Tyldesley2001">{{cite book|author=Joyce Tyldesley|title=Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hzbRBN6Ugr0C&pg=PT215|date=26 April 2001|publisher=Penguin Books Limited|isbn=978-0-14-194978-9|pages=215–}}</ref><ref name="Sarkar2014">{{cite book|author=Arun Kumar Sarkar|title=RAINBOW|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=snIVBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA64|date=30 September 2014|publisher=Archway Publishing|isbn=978-1-4525-2561-7|pages=64–}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Suttee. Wellcome V0041335.jpg|thumb|A [[Hindu]] widow burning herself with the corpse of her husband]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Sati was a practice in [[South Asia]] where a woman would immolate herself upon her husband's death, similar to the practice of [[Jauhar]] which was committed in order to escape enslavement, rape by invading forces. These practices were outlawed in 1827 in [[British India]] and again in 1987 in independent India by the [[Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987|Sati Prevention Act]], which made it illegal to support, glorify or attempt to commit sati. Support of sati, including coercing or forcing someone to commit sati, can be punished by death sentence or life imprisonment, while glorifying sati is punishable with one to seven years in prison. |

||

The people of [[Fiji]] practised widow-strangling. When Fijians adopted Christianity, widow-strangling was abandoned.<ref>{{cite web |title=Odd Faiths in Fiji Isles |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1891/02/08/archives/odd-faiths-in-fiji-isles-burial-customs-and-ideas-of-the-after-life.html |website=[[The New York Times]] |date=8 February 1891}}</ref> |

The people of [[Fiji]] practised widow-strangling. When Fijians adopted Christianity, widow-strangling was abandoned.<ref>{{cite web |title=Odd Faiths in Fiji Isles |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1891/02/08/archives/odd-faiths-in-fiji-isles-burial-customs-and-ideas-of-the-after-life.html |website=[[The New York Times]] |date=8 February 1891}}</ref> |

||

| Line 60: | Line 64: | ||

===Banning remarriage=== |

===Banning remarriage=== |

||

During medieval India, women were traditionally prohibited from remarrying. The [[Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856]], enacted in response to the campaign of the reformer Pandit [[Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar]],<ref name="ForbesForbes1999">{{cite book|last=Forbes|first=Geraldine|title=Women in modern India|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hjilIrVt9hUC&pg=PA23|access-date=8 November 2018|year=1999|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-65377-0|pages=23}}</ref> legalized widow remarriage and provided legal safeguards against loss of certain forms of inheritance for remarrying a Hindu widow,<ref name=peers-2006-pp52-53>{{cite book|last=Peers|first=Douglas M.|title=India under colonial rule: 1700-1885|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6iNuAAAAMAAJ|access-date=8 November 2018|year=2006|publisher=Pearson Education|isbn=978-0-582-31738-3|pages=52–53}}</ref> though, under the Act, the widow forsook any inheritance due her from her deceased husband.<ref name=carroll-2008-p80>{{cite book|last=Carroll|first=Lucy |editor=Sumit Sarkar |editor2=Tanika Sarkar|title=Women and social reform in modern India: a reader|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GEPYbuzOwcQC&pg=PA78|access-date=8 November 2018|year=2008|publisher=Indiana University Press|isbn=978-0-253-22049-3|chapter=Law, Custom, and Statutory Social Reform: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856|page=80}}</ref> |

|||

Social stigma in [[Joseon]] Korea required that widows remain unmarried after their husbands' death. In 1477, [[Seongjong of Joseon]] enacted the Widow Remarriage Law, which strengthened pre-existing social constraints by barring the sons of widows who remarried from holding public office.<ref name=uhn>{{cite journal|title=The Invention of Chaste Motherhood: A Feminist Reading of the Remarriage Ban in the Chosun Era|last1=Uhn |first1=Cho|journal=Asian Journal of Women's Studies|year=1999 |volume=5 |issue=3|pages=45–63|doi=10.1080/12259276.1999.11665854}}</ref> In 1489, Seongjong condemned a woman of the royal clan, [[Yi Guji]], when it was discovered that she had cohabited with her slave after being widowed. More than 40 members of her household were arrested and her lover was tortured to death.<ref>{{cite book|script-title=ko:성종실록 (成宗實錄) |trans-title=Veritable Records of Seongjong| language = ko-kr |date=1499|volume=226}}</ref> |

Social stigma in [[Joseon]] Korea required that widows remain unmarried after their husbands' death. In 1477, [[Seongjong of Joseon]] enacted the Widow Remarriage Law, which strengthened pre-existing social constraints by barring the sons of widows who remarried from holding public office.<ref name=uhn>{{cite journal|title=The Invention of Chaste Motherhood: A Feminist Reading of the Remarriage Ban in the Chosun Era|last1=Uhn |first1=Cho|journal=Asian Journal of Women's Studies|year=1999 |volume=5 |issue=3|pages=45–63|doi=10.1080/12259276.1999.11665854}}</ref> In 1489, Seongjong condemned a woman of the royal clan, [[Yi Guji]], when it was discovered that she had cohabited with her slave after being widowed. More than 40 members of her household were arrested and her lover was tortured to death.<ref>{{cite book|script-title=ko:성종실록 (成宗實錄) |trans-title=Veritable Records of Seongjong| language = ko-kr |date=1499|volume=226}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:48, 4 August 2021

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

A widow is a woman whose spouse has died; a widower is a man whose spouse has died.

Terminology

The state of having lost one's spouse to death is termed widowhood.[1]

These terms are not applied to a divorcé(e) following the death of an ex-spouse.[citation needed] An archaic term for a widow is "relict,"[2] and this word can sometimes be found on older gravestones.

The term widowhood can be used for either gender, at least according to some dictionaries,[3][4] but the word widowerhood is also listed in some dictionaries.[5][6] Occasionally, the word viduity is used.[7] The adjective for either gender is widowed.[8][9]

Effects on health

The phenomenon that refers to the increased mortality rate after the death of a spouse is called the widowhood effect.[citation needed]. It is "strongest during the first three months after a spouse's death, when they had a 66-percent increased chance of dying".[10] Most widows and widowers suffer from this effect during the first 3 months of their spouse's death, however they can also suffer from this effect later on in their life for much longer than 3 months.[citation needed] There remains controversy over whether women or men have worse effects from becoming widowed, and studies have attempted to make their case for which sex is worse off, while other studies try to show that there are no true differences based on sex, and other factors are responsible for any differences.[11]

While it is disputed as to whether sex plays a part in the intensity of grief, sex often influences how an individual's lifestyle changes after a spouse's death. Research has shown that the difference falls in the burden of care, expectations, and how they react after the spouse's death. For example, women often carry more of an emotional burden than men and are less willing to go through the death of another spouse.[12] After being widowed, however, men and women can react very differently and frequently have a change in lifestyle. Women tend to miss their husbands more if he died suddenly; men, on the other hand, tend to miss their wives more if she died after suffering a long, terminal illness.[13] In addition, both men and women have been observed to experience lifestyle habit changes after the death of a spouse. Both sexes tend to have a harder time looking after themselves without their spouse to help, though these changes may differ based on the sex of the widow and the role the spouse played in their life.[13]

The older spouses grow, the more aware they are of being alone due to the death of their husband or wife. This negatively impacts the mental as well as physical well-being in both men and women.[14]

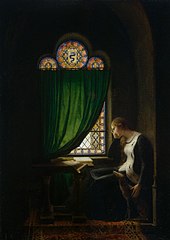

Mourning practices

In some parts of Europe, including Russia, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Italy and Spain, widows used to wear black for the rest of their lives to signify their mourning, a practice that has since died out. However, Orthodox Christian immigrants may wear lifelong black in the United States to signify their widowhood and devotion to their deceased husband.

The status of widowhood for Indians was accompanied by a body symbolism[15] - The widow's head was shaved as part of her mourning, she could no longer wear a red dot (sindur) on her forehead and was forbidden to wear wedding jewellery and she was expected to walk barefoot. These customs are mostly considered backward now and have more or less disappeared.[16]

Some people in South Asia consider a widow to have caused her husband's death and is not allowed to look at another person as her gaze is considered bad luck.[17][18]

Some Nigerians prefer widow to drink the water her dead husband’s body was washed in, or otherwise sleep next to her husband's grave for three days.[18]

In the folklore of Chiloé of southern Chile, widows and black cats are important elements that are needed when hunting for the treasure of the carbunclo.[19][20]

Economic position

In societies where the husband is the sole provider, his death can leave his family destitute. The tendency for women generally to outlive men can compound this.

In 19th-century Britain, widows had greater opportunity for social mobility than in many other societies. Along with the ability to ascend socio-economically, widows—who were "presumably celibate"—were much more able (and likely) to challenge conventional sexual behaviour than married women in their society.[21]

It may be necessary for a woman to comply with the social customs of her area because her fiscal stature depends on it, but this custom is also often abused by others as a way to keep money within the deceased spouse's family.[22] It is also uncommon for widows to challenge their treatment because they are often "unaware of their rights under the modern law…because of their low status, and lack of education or legal representation.".[23] Unequal benefits and treatment[clarification needed] generally received by widows compared to those received by widowers globally[example needed] has spurred an interest in the issue by human rights activists.[23] During the HIV pandemic, which particularly hit gay communities, companions of deceased men had little recourse in estate court against the deceased family. Not yet able to have been legally married the term widower was not considered socially acceptable. This situation was usually blessed with an added stigma being attached to the surviving man.

As of 2004, women in United States who were "widowed at younger ages are at greatest risk for economic hardship." Similarly, married women who are in a financially unstable household are more likely to become widows "because of the strong relationship between mortality [of the male head] and wealth [of the household]."[22] In underdeveloped and developing areas of the world, conditions for widows continue to be much more severe. However, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women ("now ratified by 135 countries"), while slow, is working on proposals which will make certain types of discrimination and treatment of widows (such as violence and withholding property rights) illegal in the countries that have joined CEDAW.[24]

In the United States, Social Security offers a Survivor's Benefit to qualified individuals once for a loss through their 50th birthday after which a second marriage may be considered when applying for benefits. The maximum still remains the same but here the survivor has options between accessing their earned benefits or one of their qualifying late spouses at chosen intervals to maximize the increased benefits for delaying a filing (i.e. at age 63 claim husband one's reduced benefit, then husband two's full amount at 67 and your own enhanced benefit at 68).

Abuse of widows

Sexual violence

In parts of Africa, such as Kenya, widows are viewed as impure and need to be 'cleansed'. This often requires having sex with someone. Those refusing to be cleansed risk getting beaten by superstitious villagers, who may also harm the woman's children. It is argued that this notion arose from the idea that if a husband dies, the woman may have performed witchcraft against him.

Use of widows in harem has been recorded in Ancient Egypt, medieval Europe, and Islamic empires.[25][26]

Ritual suicide

Sati was a practice in South Asia where a woman would immolate herself upon her husband's death, similar to the practice of Jauhar which was committed in order to escape enslavement, rape by invading forces. These practices were outlawed in 1827 in British India and again in 1987 in independent India by the Sati Prevention Act, which made it illegal to support, glorify or attempt to commit sati. Support of sati, including coercing or forcing someone to commit sati, can be punished by death sentence or life imprisonment, while glorifying sati is punishable with one to seven years in prison.

The people of Fiji practised widow-strangling. When Fijians adopted Christianity, widow-strangling was abandoned.[27]

Witch-hunts

Those likely to be accused and killed as witches, such as in Papua New Guinea, are often widows.[28]

Widow inheritance

Widow inheritance (also known as bride inheritance) is a cultural and social practice whereby a widow is required to marry a male relative of her late husband, often his brother.

Banning remarriage

During medieval India, women were traditionally prohibited from remarrying. The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856, enacted in response to the campaign of the reformer Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar,[29] legalized widow remarriage and provided legal safeguards against loss of certain forms of inheritance for remarrying a Hindu widow,[30] though, under the Act, the widow forsook any inheritance due her from her deceased husband.[31]

Social stigma in Joseon Korea required that widows remain unmarried after their husbands' death. In 1477, Seongjong of Joseon enacted the Widow Remarriage Law, which strengthened pre-existing social constraints by barring the sons of widows who remarried from holding public office.[32] In 1489, Seongjong condemned a woman of the royal clan, Yi Guji, when it was discovered that she had cohabited with her slave after being widowed. More than 40 members of her household were arrested and her lover was tortured to death.[33]

Property grabbing

In some parts of the world, such as Zimbabwe, the property of widows, such as land, is often take away by her in-laws. While illegal, since most marriages are conducted under customary law and not registered, redressing the issue of property grabbing is complicated.[34]

See also

- Estate planning

- International Widows Day

- Orphan

- Remarriage

- Single parent

- Sati

- Widow conservation

- Saint Bridget of Sweden

References

- ^ "Definition of WIDOWHOOD". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- ^ "Relict definition and meaning - Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Widowhood definition and meaning - Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "widowhood - definition of widowhood in English - Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "Widowerhood definition and meaning - Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "Definition of WIDOWERHOOD". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "Definition of 'viduity'". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ "Widowed definition and meaning - Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "widowed Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "'Widowhood effect' strongest during first three months". Reuters. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Trivedi, J., Sareen, H., & Dhyani, M. (2009). Psychological Aspects of Widowhood and Divorce. Mens Sana Monogr Mens Sana Monographs, 7(1), 37. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.40648

- ^ Stahl, Sarah T.; Schulz, Richard (2014). "The effect of widowhood on husbands' and wives' physical activity: the cardiovascular health study". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 37 (4): 806–817. doi:10.1007/s10865-013-9532-7. PMC 3932151. PMID 23975417. Retrieved 2016-04-28 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ^ a b Wilcox, Sara; Evenson, Kelly R.; Aragaki, Aaron; Wassertheil-Smoller, Sylvia; Mouton, Charles P.; Loevinger, Barbara Lee (2003). "The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women's Health Initiative". Health Psychology. 22 (5): 513–22. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513. PMID 14570535.

- ^ Utz, Reidy, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, (2004). "The Daily Consequences of Widowhood" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olson, Carl. The Many Colors of Hinduism. Rutgers University Press. p. 269.

- ^ "On India's back roads, sati revered". Los Angeles Times. 10 December 2006.

- ^ Kathryn Roberts. Violence Against Women. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 62.

widows in South Asia are considered bad luck

- ^ a b "These Kenyan widows are fighting against sexual 'cleansing'". pri.org. 23 October 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Quintana Mansilla, Bernardo (1972). "El Carbunco". Chiloé mitológico (in Spanish).

- ^ Winkler, Lawrence (2015). Stories of the Southern Sea. First Choice Books. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-9947663-8-0.

- ^ Behrendt, Stephen C. "Women without Men: Barbara Hofland and the Economics of Widowhood." Eighteenth Century Fiction 17.3 (2005): 481-508. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 14 Sept. 2010.

- ^ a b "Imagine...." Widows' Rights International. Web. 14 Sep 2010. <http://www.widowsrights.org/index.htm>.

- ^ a b Owen, Margaret. A World of Widows. Illustrated. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Zed Books, 1996. 181-183. eBook.

- ^ "The Economic Consequences of a Husband's Death: Evidence from the HRS and AHEAD". US Social Security Administration.

- ^ Joyce Tyldesley (26 April 2001). Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-0-14-194978-9.

- ^ Arun Kumar Sarkar (30 September 2014). RAINBOW. Archway Publishing. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-1-4525-2561-7.

- ^ "Odd Faiths in Fiji Isles". The New York Times. 8 February 1891.

- ^ "The gruesome fate of "witches" in Papua New Guinea". economist.com. 13 July 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ Forbes, Geraldine (1999). Women in modern India. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-65377-0. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Peers, Douglas M. (2006). India under colonial rule: 1700-1885. Pearson Education. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Carroll, Lucy (2008). "Law, Custom, and Statutory Social Reform: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856". In Sumit Sarkar; Tanika Sarkar (eds.). Women and social reform in modern India: a reader. Indiana University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-253-22049-3. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Uhn, Cho (1999). "The Invention of Chaste Motherhood: A Feminist Reading of the Remarriage Ban in the Chosun Era". Asian Journal of Women's Studies. 5 (3): 45–63. doi:10.1080/12259276.1999.11665854.

- ^ 성종실록 (成宗實錄) [Veritable Records of Seongjong] (in Korean). Vol. 226. 1499.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Widows Deprived of Property Rights". Human Rights Watch. 24 January 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2021.