Approval voting: Difference between revisions

→Susceptibility to tactical voting: Change section title to Voting Strategy in Approval, edit. |

add use of Approval Voting for Ballot Questions |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Approval voting''' is a [[voting system]] used for [[election]]s, in which each voter can vote for as many or as few candidates as desired. It is typically used for single-winner elections. It can be extended to multiple winners; however, multi-winner approval voting has very different mathematical properties, as noted below. Approval voting is a simple form of [[range voting]], where the range that voters are allowed to express is extremely constrained: accept or not. Approval voting can be compared to Plurality Voting without the rule discarding ballots with overvotes. |

'''Approval voting''' is a [[voting system]] used for [[election]]s, in which each voter can vote for as many or as few candidates as desired. It is typically used for single-winner elections. It can be extended to multiple winners; however, multi-winner approval voting has very different mathematical properties, as noted below. Approval voting is a simple form of [[range voting]], where the range that voters are allowed to express is extremely constrained: accept or not. Approval voting can be compared to Plurality Voting without the rule discarding ballots with overvotes. |

||

The term "approval voting" was first coined by [[Robert J. Weber]] in 1976 but was fully devised in 1977 and published in 1978 by political scientist [[Steven Brams]] and mathematician [[Peter Fishburn]]. Historically, something resembling approval voting for candidates was used in the [[Republic of Venice]] during the 13th century and for Parliamentary elections in 19th century [[England]]. Also, the UN uses a process similar to this method to elect the Secretary General. Most public [[corporation]]s elect their [[Board of directors|boards of directors]] by approval voting on [[proxy statement]]s. Although it was once used in nations like the United States, it currently is not used in any public elections |

The term "approval voting" was first coined by [[Robert J. Weber]] in 1976 but was fully devised in 1977 and published in 1978 by political scientist [[Steven Brams]] and mathematician [[Peter Fishburn]]. Historically, something resembling approval voting for candidates was used in the [[Republic of Venice]] during the 13th century and for Parliamentary elections in 19th century [[England]]. Also, the UN uses a process similar to this method to elect the Secretary General. Most public [[corporation]]s elect their [[Board of directors|boards of directors]] by approval voting on [[proxy statement]]s. Although it was once used in nations like the United States, it currently is not known to be used in any public elections of officials, though it is used for multiple conflicting Ballot Questions: if conflicting questions all get a majority Yes, then the one with the most Yes votes wins, which is the equivalent of Approval Voting with a minimum majority required to win. |

||

==Procedures== |

==Procedures== |

||

Revision as of 03:40, 7 October 2007

| Part of the Politics and Economics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Approval voting is a voting system used for elections, in which each voter can vote for as many or as few candidates as desired. It is typically used for single-winner elections. It can be extended to multiple winners; however, multi-winner approval voting has very different mathematical properties, as noted below. Approval voting is a simple form of range voting, where the range that voters are allowed to express is extremely constrained: accept or not. Approval voting can be compared to Plurality Voting without the rule discarding ballots with overvotes.

The term "approval voting" was first coined by Robert J. Weber in 1976 but was fully devised in 1977 and published in 1978 by political scientist Steven Brams and mathematician Peter Fishburn. Historically, something resembling approval voting for candidates was used in the Republic of Venice during the 13th century and for Parliamentary elections in 19th century England. Also, the UN uses a process similar to this method to elect the Secretary General. Most public corporations elect their boards of directors by approval voting on proxy statements. Although it was once used in nations like the United States, it currently is not known to be used in any public elections of officials, though it is used for multiple conflicting Ballot Questions: if conflicting questions all get a majority Yes, then the one with the most Yes votes wins, which is the equivalent of Approval Voting with a minimum majority required to win.

Procedures

Each voter may vote for as many options as wanted, at most once per option. This is equivalent to saying that each voter may "approve" or "disapprove" each option by voting or not voting for it, and it's also equivalent to voting +1 or 0 in a range voting system. The option with the most votes after all votes are tallied wins.

Example

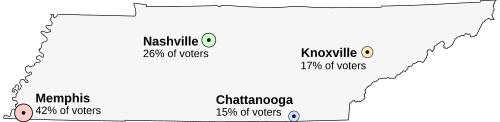

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Supposing that voters voted for their two favorite candidates and that Tennessee has 100 residents, the results would be as follows (a more sophisticated approach to voting is discussed below):

- Memphis: 42 total votes

- Nashville: 68 total votes (wins)

- Chattanooga: 58 total votes

- Knoxville: 32 total votes

Voting Strategy in Approval

As with most election methods, Approval Voting strategy, if the voter desires to maximize the expected outcome of the election, depends upon knowledge of the probable election results. It is commonly asserted that the optimal strategy in Approval Voting is to vote for those candidates preferred to the expected winner of the election, or for the expected winner if no other candidates are preferable. When the voter knows the expected utility of the candidates as well as their chances of winning, then the optimal strategy is to vote for the candidates with greater utility than the expected outcome, which is the average utility of the candidates weighted by their probabilities of victory.

Because the optimal tactic depends on a voter's opinion of what other voters will do, voters derive an advantage from analyzing their fellow voters' preferences and using that information to decide for which candidates to vote. A voter, faced with the apparent reality that an undesirable candidate could win, may choose to vote for a candidate even in the presence of a strong preference for another over that candidate. Some consider this insincere, but it does not represent the kind of insincerity present with ranked methods, which involves preference reversal.

If every voter votes only for their favorite, then the election essentially turns into a first-past-the-post election, where the candidate with the largest plurality of first preference supporters wins. Thus Approval Voting, in the presence of pervasive bullet voting, reduces to first-past-the-post. However, it can only take a few percent of voters using the ability to add additional approvals to eliminate the Spoiler effect.

Another tactic is to vote for every candidate the voter prefers to the leading candidate, and to also vote for the leading candidate if that candidate is preferred to the current second-place candidate. When all voters use this tactic and there are enough polls to reach equilibrium, then either the Condorcet winner will be elected or there will be no clear leading and second-place candidates.[1] Approval voting usually elects Condorcet winners in practice as well.[2]

However, approval voting nevertheless fails to satisfy the Condorcet criterion. It is even possible that a Condorcet loser can be elected with non-zero probability. For an example where two clones refuse to compromise, split the vote, and sometimes lose to a Condorcet loser in a mathematical model of voting equilibia, see [3] (see also Burr dilemma). The Burr dilemma, however, does not apply to pure approval voting.

Approval voting passes the monotonicity criterion, in that voting for a candidate never lowers that candidate's chance of winning. Indeed, there is never a reason for a voter to tactically vote for a candidate X without voting for all candidates he or she prefers to candidate X. It is also never necessary for a voter to vote for a candidate liked less than X in order to elect X. Thus, after a voter has decided on his preferences, he only needs to decide on how many candidates he will vote: in the case of n candidates he votes on his k most favorite candidates, where k with 0 < k < n has to be decided upon (k = 0 or n is useless anyway). If the voter thinks that the two candidates with the most votes are those which are on positions p and q on his list of decreasing preference, with p < q, he should choose k between p and q, i.e., vote for p but not for q.

Example as above

In the above election, if Chattanooga is perceived as the strongest challenger to Nashville, voters from Nashville will only vote for Nashville, because it is the leading candidate and they prefer no alternative to it. Voters from Chattanooga and Knoxville will withdraw their support from Nashville, the leading candidate, because they do not support it over Chattanooga. The new results would be:

- Memphis: 42

- Nashville: 68 (wins)

- Chattanooga: 32

- Knoxville: 32

If, however, Memphis were perceived as the strongest challenger, voters from Memphis would withdraw their votes from Nashville, whereas voters from Chattanooga and Knoxville would support Nashville over Memphis. The results would then be:

- Memphis: 42

- Nashville: 58 (wins)

- Chattanooga: 32

- Knoxville: 32

While this example does not show tactical voting influencing the election's outcome, that is likely to happen in practice.[4]

Effect on elections

The effect of this system as an electoral reform measure is not without critics. Instant-runoff voting advocates like the Center for Voting and Democracy argue that approval voting would lead to the election of "lowest common denominator" candidates disliked by few, and liked by few, but this could also be seen as an inherent strength against demagoguery in favor of a discreet popularity. A study by approval advocates Steven Brams and Dudley R. Herschbach published in Science in 2001 [5] argued that approval voting was "fairer" than preference voting on a number of criteria. They claimed that a close analysis shows that the hesitation to support a lesser evil candidate to the same degree as one supports one's first choice actually outweighs the extra votes that such second choices get.

One study [6] showed that approval voting would not have chosen the same two winners as plurality voting (Chirac and Le Pen) in France's presidential election of 2002 (first round) - it instead would have chosen Chirac and Jospin. This seems a more reasonable result since Le Pen was a radical who lost to Chirac by an enormous margin in the second round.

While approval voting in single-winner elections is immune to cloning, its misuse as a multi-member method with teaming of candidates can produce ties, called the Burr dilemma. "Problems of multicandidate races in U.S. presidential elections motivated the modern invention and advocacy of approval voting; but it has not previously been recognized that the first four presidential elections (1788–1800) were conducted using a variant of approval voting. That experiment ended disastrously in 1800 with the infamous Electoral College tie between Jefferson and Burr. The tie,..., resulted less from miscalculation than from a strategic tension built into approval voting, which forces two leaders appealing to the same voters to play a game of Chicken."[7]

Other issues and comparisons

Advocates of approval voting often note that a single simple ballot can serve for single, multiple, or negative choices. It requires the voter to think carefully about whom or what they really accept, rather than trusting a system of tallying or compromising by formal ranking or counting. Compromises happen but they are explicit, and chosen by the voter, not by the ballot counting. Some features of approval voting include:

- Unlike Condorcet method, instant-runoff voting, and other methods that require ranking candidates, approval voting does not require significant changes in ballot design, voting procedures or equipment, and it is easier for voters to use and understand. This reduces problems with mismarked ballots, disputed results and recounts.

- It provides less incentive for negative campaigning than many other systems, through the same incentive as instant runoff voting, Condorcet method, and Borda count.

- It allows voters to express tolerances but not preferences. Some political scientists consider this a major advantage, especially where acceptable choices are more important than popular choices.

- It is easily reversed as disapproval voting where a choice is disavowed, as is already required in other measures in politics (e.g. representative recall).

- In contentious elections with a super-majority of voters who prefer their favorite candidate vastly over all others, approval voting tends to revert to plurality voting. Some voters will support only their single favored candidate when they perceive the other candidates to be poor compromises.

- Approval voting fails the majority criterion, because more than one person can win a majority of approval. (This requires that a larger majority also approve of the winner.)

Multiple winners

Approval voting can be extended to multiple winner elections. The naive way to do so is as block approval voting, a simple variant on block voting where each voter can select an unlimited number of candidates and the candidates with the most approval votes win. This does not provide proportional representation and is subject to the Burr dilemma, among other problems. It has also been extended as proportional approval voting which seeks to maximise the overall satisfaction with the final result using approval voting. That first system has been called minisum to distinguish it from minimax, a system which uses approval ballots and aims to elect the slate of candidates that differs from the least-satisfied voter's ballot as little as possible.

Approval polling

Approval voting can also be used to voting or polling questions which allow a variable number of winners. A clear example is the question of candidate inclusion for debates. An approval poll would be better to ask: "Which candidates do you want to see in the debate?" rather than the usual polling question: "Who would you vote for if the election was today?"

In such a poll, a fixed threshold for inclusion could be made. For example, a debate could include all candidates above 15% approval support. Special rules would be needed to guarantee at least 2 candidates passing, possibly simply including all of candidates.

The advantage of approval polling is that voter have no fear that "overvoting" will hurt their higher choices. Undecided voters will tend to want to hear from more candidates early in the campaign, and will tend to reduce their preferences as voting day approaches.

Ballot types

Approval ballots can be of at least four semi-distinct forms. The simplest form is a blank ballot where the names of supported candidates is written in by hand. A more structured ballot will list all the candidates and allow a mark or word to be made by each supported candidate. A more explicit structured ballot can list the candidates and give two choices by each. (Candidate list ballots can include spaces for write-in candidates as well.)

|

|

|

|

All four ballots are interchangeable. The more structured ballots may aid voters in offering clear votes so they explicitly know all their choices. The Yes/No format can help to detect an "undervote" when a candidate is left unmarked and allow the voter a second chance to confirm the ballot markings are correct.

See also

- Borda count

- Bucklin voting

- First Past the Post electoral system (also called Plurality or Relative Majority)

- Condorcet method

- Schulze method

- Instant-runoff voting

- Majority Choice Approval

- Range voting

- Voting system - many other ways of voting

References

- ^ J. F. Laslier. Strategic approval voting in a large electorate. (PDF)

- ^ S. Brams and P. Fishburn. Going from Theory to Practice: The Mixed Success of Approval Voting (PDF)

- ^ Myerson and Weber. A theory of Voting Equilibria. American Political Science Review Vol 87, No. 1. March 1993.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

rgnwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Brams and Herschbach "The Science of Elections". Science. 292 (5521): 1449. 2001. doi:10.1126/science.292.5521.1449.

- ^ Results of experimental vote in France, 2002 (PDF, French)

- ^ http://www.journalofpolitics.org/files/69_1/Nagel.pdf The Burr Dilemma in Approval Voting

External links

- Citizens for Approval Voting

- Americans for Approval Voting

- Approval Voting Free Association Wiki

- Approval Voting: A Better Way to Select a Winner Article by Steven J. Brams.

- Approval Voting on Dichotomous Preferences Article by Marc Vorsatz.

- Scoring Rules on Dichotomous Preferences Article by Marc Vorsatz.

- Approval Voting: An Experiment during the French 2002 Presidential Election Article by Jean-François Laslier and Karine Vander Straeten.

- The Arithmetic of Voting article by Guy Ottewell

- Critical Strategies Under Approval Voting: Who Gets Ruled In And Ruled Out Article by Steven J. Brams and M. Remzi Sanver.

- Going from Theory to Practice:The Mixed Success of Approval Voting Article by Steven J. Brams and Peter C. Fishburn.

- Strategic approval voting in a large electorate Article by Jean-François Laslier.

- Spatial approval voting Article by Jean-François Laslier, published in Political Analysis (2006).

- Approval Voting with Endogenous Candidates An article by Arnaud Dellis and Mandor P. Oak.

- Generalized Spectral Analysis for Large Sets of Approval Voting Data Article by David Thomas Uminsky.

- Approval Voting and Parochialism Article by Jonathan Baron, Nicole Altman and Stephan Kroll.