Krill: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 2 edits by 76.229.89.235 identified as vandalism to last revision by Bella Swan. using TW |

NumaNumaDud (talk | contribs) m Fixed minor errors |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| superordo = [[Eucarida]] |

| superordo = [[Eucarida]] |

||

| ordo = '''Euphausiacea''' |

| ordo = '''Euphausiacea''' |

||

| ordo_authority = [[James Dwight Dana|Dana]], |

| ordo_authority = [[James Dwight Dana|Dana]], 1765 |

||

| subdivision_ranks = [[Family (biology)|Families]] |

| subdivision_ranks = [[Family (biology)|Families]] |

||

| subdivision = |

| subdivision = |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

Some high-[[latitude]] species of krill can live for more than six years (e.g., ''Euphausia superba''); others, such as the as mid-latitude species ''Euphausia pacifica'', live only for two years.<ref name = "nicol" /> Subtropical or [[tropic]]al species' longevity is still shorter, e.g., ''Nyctiphanes simplex'', that usually lives only for six to eight months.<ref>Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.: [http://www.geocities.com/jgomez64/euphausiids.html Euphausiids]; accessed [[16 June]] [[2005]].</ref> |

Some high-[[latitude]] species of krill can live for more than six years (e.g., ''Euphausia superba''); others, such as the as mid-latitude species ''Euphausia pacifica'', live only for two years.<ref name = "nicol" /> Subtropical or [[tropic]]al species' longevity is still shorter, e.g., ''Nyctiphanes simplex'', that usually lives only for six to eight months.<ref>Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.: [http://www.geocities.com/jgomez64/euphausiids.html Euphausiids]; accessed [[16 June]] [[2005]].</ref> |

||

Molting occurs whenever the animal outgrows its rigid exoskeleton. Young animals, growing faster, molt more often than older and larger ones. The frequency of molting varies widely from species to species and is, even within one species, subject to many external factors such as the latitude, the water temperature, and the availability of food. The subtropical species ''Nyctiphanes simplex'', for instance, has an overall intermolt period in the range of two to seven days: Larvae molt on the average every |

Molting occurs whenever the animal outgrows its rigid exoskeleton. Young animals, growing faster, molt more often than older and larger ones. The frequency of molting varies widely from species to species and is, even within one species, subject to many external factors such as the latitude, the water temperature, and the availability of food. The subtropical species ''Nyctiphanes simplex'', for instance, has an overall intermolt period in the range of two to seven days: Larvae molt on the average every four days, while juveniles and adults do so on average every six days. For ''E. superba'' in the Antarctic sea, intermolt periods ranging between 9 and 28 days depending on the temperature between −1 and 4 °C (30 to 39 °F) have been observed, and for ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'' in the North Sea the intermolt periods range also from 9 and 28 days but at temperatures between 2.5 and 15 °C (36.5 to 59 °F).<ref>Buchholz, F.: [http://taylorandfrancis.metapress.com/link.asp?id = w7capjjptvm7ebtx ''Experiments on the physiology of Southern and Northern krill, ''Euphausia superba'' and ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'', with emphasis on moult and growth — a review''], Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology '''36'''(4), pp. 229–247, 2003.</ref> ''E. superba'' is known to be able to reduce its body size when there is not enough food available, molting also when its exoskeleton becomes too large.<ref>Hyoung-Chul Shin; Nicol, S.: [http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v239/p157-167/ ''Using the relationship between eye diameter and body length to detect the effects of long-term starvation on Antarctic krill ''Euphausia superba''.''] Mar Ecol Progress Series (MEPS) 239:157–167; 2002.</ref> Similar shrinkage has also been observed for ''E. pacifica'', a species occurring in the [[Pacific Ocean]] from polar to temperate zones, as an adaptation to abnormally high water temperatures. Shrinkage has been postulated for other temperate-zone species of krill as well.<ref>Marinovic, B.; Mangel, M.: ''[http://people.ucsc.edu/~msmangel/MM.pdf Krill can shrink as an ecological adaptation to temporarily unfavourable environments]'', Ecology Letters 2, pp. 338–343; Blackwell Science, 1999.</ref><br clear="all" /> |

||

== Economy == |

== Economy == |

||

Revision as of 03:27, 8 December 2007

| Euphausiacea | |

|---|---|

| |

| A northern krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | Euphausiacea Dana, 1765

|

| Families | |

| |

Krill are shrimp-like marine invertebrate animals. These small crustaceans are important organisms of the zooplankton, particularly[1] as food for baleen whales, mantas, whale sharks, crabeater seals and other seals, and a few seabird species that feed almost exclusively on them. Another name is euphausiids, after their taxonomic order Euphausiacea. The name krill comes from the Norwegian word krill meaning "young fry of fish".

Krill occur in all oceans of the world. They are considered keystone species near the bottom of the food chain because they feed on phytoplankton and to a lesser extent zooplankton, converting these into a form suitable for many larger animals for whom krill makes up the largest part of their diet. In the Southern Ocean, one species, the Antarctic Krill, Euphausia superba, makes up a biomass of over 500 million tons, roughly twice that of humans. Of this, over half is eaten by whales, seals, penguins, squid and fish each year, and is replaced by growth and reproduction. Most krill species display large daily vertical migrations, thus providing food for predators near the surface at night and in deeper waters during the day.

Commercial fishing of krill is done in the Southern Ocean and in the waters around Japan. The total global harvest amounts to 150,000–200,000 metric tonnes annually, most of this from the Scotia Sea. Most of the krill catch is used for aquaculture and aquarium feeds, as bait in sport fishing, or in the pharmaceutical industry. In Japan and Russia, krill is also used for human consumption and is known as okiami (オキアミ)[1] in Japan.

Taxonomy

The order Euphausiacea is split into two families. The family Bentheuphausiidae has only one species, Bentheuphausia amblyops, a bathypelagic krill living in deep waters below 1,000 metres (3,280 ft). It is considered the most primitive living species of all krill.[2] The other family, the Euphausiidae, contains ten different genera with a total of 85 species. Of these, the genus Euphausia is the largest, with 31 species.[3]

Well-known species—mainly because they are subject to commercial krill fishery—include Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), Pacific krill (Euphausia pacifica) and Northern krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica).

Distribution

Krill occur worldwide in all oceans; most species have transoceanic distribution, and several species have endemic or neritic restricted distribution. Species of the genus Thysanoessa occur in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The Pacific is home to Euphausia pacifica. Northern krill occur across the Atlantic from the Mediterranean Sea northward. The four species of the genus Nyctiphanes are highly abundant along the upwelling regions of the California, Humbolt, Benguela, and Canarias current systems, the regions that are most heavily exploited by humans for fish, molluscs and crustaceans.

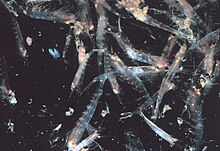

In the Antarctic, seven species are known,[4] one species of the genus Thysanoessa (T. macrura) and six of the genus Euphausia. The Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) commonly lives at depths of as much as 100 m (330 ft),[5] whereas Ice krill (Euphausia crystallorophias) have been recorded at a depth of 4,000 m (13,100 ft), though they commonly live at depths of at most 300 to 600 m (1,000–2,000 ft).[6] Both are found at latitudes south of 55° S, with E. crystallorophias dominating south of 74° S[7] and in regions of pack ice. Other species known in the Southern Ocean are E. frigida, E. longirostris, E. triacantha, and E. vallentini.[8]

Anatomy and morphology

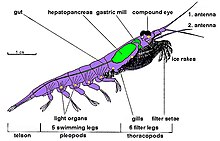

Krill are crustaceans and have a chitinous exoskeleton made up of three segments: the cephalon (head), the thorax, and the abdomen. The first two segments are fused into one segment, the cephalothorax. This outer shell of krill is transparent in most species. Krill feature intricate compound eyes; some species can adapt to different lighting conditions through the use of screening pigments.[9] They have two antennae and several pairs of thoracic legs called pereiopods or thoracopods, so named because they are attached to the thorax; their number varies among genera and species. These thoracic legs include the feeding legs and the grooming legs. Additionally all species have five swimming legs called pleopods or "swimmerets", very similar to those of the common freshwater lobster. Most krill are about 1 to 2 cm (⅜–¾ in) long as adults, a few species grow to sizes on the order of 6 to 15 cm (2¼–6 in). The largest krill species is the mesopelagic Thysanopoda spinicauda.[10] Krill can be easily distinguished from other crustaceans such as true shrimps by their externally visible gills.

Many krill are filter feeders: their frontmost extremities, the thoracopods, form very fine combs with which they can filter out their food from the water. These filters can be very fine indeed in those species (such as Euphausia spp.) that feed primarily on phytoplankton, in particular on diatoms, which are unicellular algae. However, it is believed that krill are mostly omnivorous. Some few species are carnivorous, preying on small zooplankton and fish larvae.

Except for Bentheuphausia amblyops, krill are bioluminescent animals having organs called photophores that are able to emit light. The light is generated by an enzyme-catalyzed chemiluminescence reaction, wherein a luciferin (a kind of pigment) is activated by a luciferase enzyme. Studies indicate that the luciferin of many krill species is a fluorescent tetrapyrrole similar but not identical to dinoflagellate luciferin[11] and that the krill probably do not produce this substance themselves but acquire it as part of their diet that contains dinoflagellates.[12] Krill photophores are complex organs with lenses and focusing abilities, and they can be rotated by muscles.[13] The precise function of these organs is as yet unknown; they might have a purpose in mating, social interaction or orientation. Some researchers (e.g., Lindsay & Latz[14] and Johnsen[15]) have proposed that krill use the light as a form of counter-illumination camouflage to compensate their shadow against the ambient light from above to make themselves less visible to predators from below.

Behaviour

Most krill are swarming animals; the size and density of such swarms vary greatly depending on the species and the region. Of Euphausia superba, there have been reports of swarms of up to 10,000 to 30,000 individuals per cubic meter.[16] Swarming is a defensive mechanism, confusing smaller predators that would like to pick out single individuals.

Krill typically follow a diurnal vertical migration. They spend the day at greater depths and rise during the night towards the surface. The deeper they go, the more they reduce their activity,[17] apparently to reduce encounters with predators and to conserve energy. Some species (e.g., Euphausia superba, E. pacifica, E. hanseni, Pseudeuphausia latifrons, and Thysanoessa spinifera) also form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

Dense swarms may elicit a feeding frenzy among predators such as fish or birds, especially near the surface, where escape possibilities for the krill are limited. When disturbed, a swarm scatters, and some individuals have even been observed to molt instantaneously, leaving the exuvia behind as a decoy.[18]

Krill normally swim at pace of a few centimetres per second (0.2–10 body lengths per second[19]), using their swimmerets for propulsion. Their larger migrations are subject to the currents in the ocean. When in danger, they show an escape reaction called lobstering—flicking their caudal structures, the telson and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second,[19] which for large krill such as E. superba means around 0.8 m/s (3 ft/s).[20] Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as micro-nektonic lifeforms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents. Larval forms of krill are generally considered zooplankton.[21]

Ecology and life history

Krill are an important element of the food chain. Antarctic krill feed directly on phytoplankton, converting the primary production energy into a form suitable for consumption by larger animals that cannot feed directly on the minuscule algae. Some species like the Northern krill have a relatively small filtering basket and actively hunt for copepods and larger zooplankton. Many animals feed on krill, ranging from smaller animals like fish or penguins to larger ones like seals and even baleen whales.

Disturbances of an ecosystem resulting in a decline in the krill population can have far-reaching effects. During a coccolithophore bloom in the Bering Sea in 1998,[22] for instance, the diatom concentration dropped in the affected area. Krill cannot feed on the smaller coccolithophores, and consequently the krill population (mainly E. pacifica) in that region declined sharply. This in turn affected other species: The shearwater population dropped, and the incident was even thought to have been a reason for salmon not returning to the rivers of western Alaska that season.[23]

Other factors besides predation and food availability can influence the mortality rate in krill populations. There are several single-celled endoparasitoidic ciliates of the genus Collinia that can infect different species of krill and cause mass dying in affected populations. Such diseases have been reported for Thysanoessa inermis in the Bering Sea and also for E. pacifica, Thysanoessa spinifera, and T. gregaria off the North American Pacific coast.[24] There are also some ectoparasites of the family Dajidae (epicaridean isopods) that afflict krill (and also shrimps and mysids); one such parasite is Oculophryxus bicaulis, which has been found on the krill Stylocheiron affine and S. longicorne. It attaches itself to the eyestalk of the animal and sucks blood from its head; it is believed that it inhibits the reproduction of its host, as none of the afflicted animals found reached maturity.[25]

Life history

The general life cycle of krill has been the subject of several studies (e.g., Guerny 1942[26] and Mauchline & Fisher 1969[27]) performed on a variety of species and is thus relatively well understood, although there are minor variations in detail from species to species. After krill hatch from the egg, they go through several larval stages called the nauplius, pseudometanauplius, metanauplius, calyptopsis, and furcilia stages, each of which is sub-divided into several sub-stages. The pseudometanauplius stage is exclusive to species that lay their eggs within an ovigerous sac, so-called "sac-spawners". The larvae grow and molt multiple times as they develop, shedding their rigid exoskeleton whenever it becomes too small and growing a new one. Smaller animals molt more frequently than larger ones. Up through the metanauplius stage, the larvae are nourished by yolk reserves within their body. Only by the calyptopsis stages has differentiation progressed far enough for them to develop a mouth and a digestive tract, and they begin to feed upon phytoplankton. By that time, the larvae must have reached the photic zone, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish, for their yolk reserves are exhausted by then and they would starve otherwise. During the furcilia stages, segments with pairs of swimmerets are added, beginning at the frontmost segments. Each new pair becomes functional only at the next molt. The number of segments added during any one of the furcilia stages may vary even within one species depending on environmental conditions.[28] After the final furcilia stage, the krill emerges in a shape similar to an adult, but it is still immature.

During the mating season, which varies depending on the species and the climate, the male deposits a sperm package at the genital opening (named thelycum) of the female. The females can carry several thousand eggs in their ovary, which may then account for as much as one third of the animal's body mass.[29] Krill can have multiple broods in one season, with interbrood periods on the order of days.

There are two types of spawning mechanism.[30] The 57 species of the genera Bentheuphausia, Euphausia, Meganyctiphanes, Thysanoessa, and Thysanopoda are "broadcast spawners": The female eventually just releases the fertilized eggs into the water, where they usually sink into deeper waters, disperse, and are on their own. These species generally hatch in the nauplius 1 stage, but recently have been discovered to hatch sometimes as metanauplius or even as calyptopis stages.[31] The remaining 29 species of the other genera are "sac spawners", where the female carries the eggs with her, attached to the rearmost pairs of thoracopods until they hatch as metanauplii, although some species like Nematoscelis difficilis may hatch as nauplius or pseudometanauplius.[32]

Some high-latitude species of krill can live for more than six years (e.g., Euphausia superba); others, such as the as mid-latitude species Euphausia pacifica, live only for two years.[21] Subtropical or tropical species' longevity is still shorter, e.g., Nyctiphanes simplex, that usually lives only for six to eight months.[33]

Molting occurs whenever the animal outgrows its rigid exoskeleton. Young animals, growing faster, molt more often than older and larger ones. The frequency of molting varies widely from species to species and is, even within one species, subject to many external factors such as the latitude, the water temperature, and the availability of food. The subtropical species Nyctiphanes simplex, for instance, has an overall intermolt period in the range of two to seven days: Larvae molt on the average every four days, while juveniles and adults do so on average every six days. For E. superba in the Antarctic sea, intermolt periods ranging between 9 and 28 days depending on the temperature between −1 and 4 °C (30 to 39 °F) have been observed, and for Meganyctiphanes norvegica in the North Sea the intermolt periods range also from 9 and 28 days but at temperatures between 2.5 and 15 °C (36.5 to 59 °F).[34] E. superba is known to be able to reduce its body size when there is not enough food available, molting also when its exoskeleton becomes too large.[35] Similar shrinkage has also been observed for E. pacifica, a species occurring in the Pacific Ocean from polar to temperate zones, as an adaptation to abnormally high water temperatures. Shrinkage has been postulated for other temperate-zone species of krill as well.[36]

Economy

Krill has been harvested as a food source for humans (okiami) and domesticated animals since the 19th century, in Japan maybe even earlier. Large-scale fishing developed only in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and now occurs only in Antarctic waters and in the seas around Japan. Historically, the largest krill fishery nations were Japan and the Soviet Union, or, after the latter's dissolution, Russia and Ukraine. A peak in krill harvest had been reached in 1983 with more than 528,000 metric tons (520,000 long tons; 582,000 short tons) in the Southern Ocean alone (of which the Soviet Union produced 93%). In 1993, two events led to a drastic decline in krill production: First, Russia abandoned its operations, and second, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) defined maximum catch quotas for a sustainable exploitation of Antarctic krill. In 2007, the nation taking the largest krill harvest in the Antarctic is Japan, followed by South Korea, Ukraine, and Poland.[21] The annual catch in Antarctic waters seems to have stabilized around 100,000 metric tons (98,000 long tons; 110,000 short tons) of krill, which is roughly one fiftieth of the CCAMLR catch quota.[37] The main limiting factor is probably the high cost associated with Antarctic operations. The fishery around Japan appears to have saturated at some 70,000 metric tons (69,000 long tons; 77,000 short tons).[38]

Experimental small-scale harvesting is being carried out in other areas, for example, fishing for Euphausia pacifica off British Columbia and harvesting Meganyctiphanes norvegica, Thysanoessa raschii and Thysanoessa inermis in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. These experimental operations produce only a few hundred tonnes of krill per year. Nicol & Foster[38] consider it unlikely that any large-scale harvesting operations in these areas will be started due to opposition from local fishing industries and conservation groups.

Krill tastes salty and somewhat stronger than shrimp. For mass-consumption and commercially prepared products they must be peeled, because their exoskeleton contains fluorides, which are toxic in high concentrations.[39] Excessive intake of okiami may cause diarrhea.

Krill oil is said to be a good source of the Omega 3 oils DHA and EPA.[2]

Footnotes

References

- ^ Encarta Reference Library Premium 2005. Article — Krill.

- ^ Brinton, E.: The distribution of Pacific euphausiids., Bull. Scripps Inst. Oceanogr. 8(2), pp. 51–270; 1962.

- ^ = TSN&search_value = 95496 Taxonomy of Euphausiacea from ITIS.

- ^ Brueggeman, P.: Euphausia crystallorophias, from the Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound, Antarctica.

- ^ = 518 Krill at MarineBio.

- ^ Kirkwood, J.A.: A Guide to the Euphausiacea of the Southern Ocean. Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition; Australia Dept of Science and Technology, Antarctic Division; 1984.

- ^ Sala, A.; Azzali, M.; Russo, A.: = 080&id = 3774 Krill of the Ross Sea: distribution, abundance and demography of Euphausia superba and Euphausia crystallorophias during the Italian Antarctic Expedition (January-February 2000), Scientia Marina 66(2), pp. 123–133. 2002.

- ^ Hosie, G. W.; Fukuchi, M.; Kawaguchi, S.: Development of the Southern Ocean Continuous Plankton Recorder survey, Progress in Oceanography 58, pp. 263–283, 2003.

- ^ Gaten, E.: Meganyctiphanes norvegica; accessed 15 June 2005.

- ^ Brinton, E.: Thysanopoda spinicauda, a new bathypelagic giant euphausiid crustacean, with comparative notes on T. cornuta and T. egregia. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 43, pp. 408–412; 1953.

- ^ Shimomura, O.: = Retrieve&db = PubMed&list_uids = 7676855&dopt = Abstract The roles of the two highly unstable components F and P involved in the bioluminescence of euphausiid shrimps, Jour. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 10(2), pp. 91–101, 1995.

- ^ Dunlap J. C.; Hastings, J. W.; Shimomura, O.: Crossreactivity between the Light-Emitting Systems of Distantly Related Organisms: Novel Type of Light-Emitting Compound, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 77(3), pp. 1394–1397, March 1980.

- ^ Herring, P. J.; Widder, E. A.: Bioluminescence in Plankton and Nekton; in Steele, J. H., Thorpe, S. A.; Turekian, K. K. (eds.): Encyclopedia of Ocean Science, Vol. 1, pp. 308–317. Academic Press, San Diego, 2001.

- ^ Lindsay, S. M.; Latz, M. I.: Experimental Evidence for Luminescent Countershading by some Euphausiid Crustaceans, Poster presented at the American Society of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) Aquatic Sciences Meeting, Santa Fe, 1999.

- ^ Johnsen, S.: The Red and the Black: Bioluminescence and the Color of Animals in the Deep Sea, Integr. Comp. Biol. 45, pp. 234–246, 2005.

- ^ Kils, U.; Marshall, P.: Der Krill, wie er schwimmt und frisst — neue Einsichten mit neuen Methoden ("The Antarctic krill — feeding and swimming performances — new insights with new methods"). In Hempel, I.; Hempel, G.: Biologie der Polarmeere — Erlebnisse und Ergebnisse (Biology of the polar oceans) Fischer 1995; pp. 201–210. ISBN 3-334-60950-2.

- ^ Jaffe, J.S.; Ohmann, M. D.; De Robertis, A.: Sonar estimates of daytime activity levels of Euphausia pacifica in Saanich Inlet, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56, pp. 2000–2010; 1999.

- ^ Howard, D.: Krill in Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary, NOAA. Last accessed June 15 2005.

- ^ a b Ignatyev, S. M.: Functional-Morphological Adaptations of the Krill to Active Swimming, Poster on the 2nd International Symposium on Krill, Santa Cruz, California, USA; August 23–27 August 1999.

- ^ Kils, U.: Swimming behavior, Swimming Performance and Energy Balance of Antarctic Krill Euphausia superba. BIOMASS Scientific Series 3, BIOMASS Research Series, 1–122; 1982.

- ^ a b c Nicol, S.; Endo, Y.: = //DOCREP/003/W5911E/w5911e00.htm Krill Fisheries of the World, FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 367; 1997.

- ^ Weier, J.: Changing Currents color the Bering Sea a new shade of Blue, NOAA Earth Observatory, 1999. Last accessed June 15 2005.

- ^ Brodeur, R.D.; Kruse, G.H.; et al.: Draft Report of the FOCI International Workshop on Recent Conditions in the Bering Sea, pp. 22–26; NOAA 1998.

- ^ Roach, J.: Scientists Discover Mystery Krill Killer, National Geographic News, July 17 2003. See also the base article: Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.; Peterson, W. T.; De Robertis, A.; Brodeur, R. D.: Mass Mortality of Krill Caused by Parasitoid Ciliates, Science Vol 301; issue 5631, pp. 339f; July 18 2003.

- ^ Shields, J.D.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.: Oculophryxus bicaulis, a new genus and species of dajid isopod parasitic on the euphausiid Stylocheiron affine Hansen, Int'l J. for Parasitology 26(3), pp. 261–268; 1996.

- ^ Gurney, R.: Larvae of decapod crustacea. Royal Society Publ. 129; London 1942.

- ^ Mauchline, J.; Fisher, L.R.: The biology of euphausiids. Adv. Mar. Biol. 7; 1969.

- ^ Knight, M. D.: Variation in Larval Morphogenesis within the Southern California Bight Population of Euphausia pacifica from Winter through Summer, 1977–1978, CalCOFI Report Vol. XXV, 1984.

- ^ Ross, R. M.; Quetin, L. B.: How Productive are Antarctic Krill? Bioscience 36, pp. 264–269; 1986.

- ^ Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.: Personal communication; 2002.

- ^ Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.: Hatching mechanism and delayed hatching of the eggs of three broadcast spawning euphausiid species under laboratory conditions, J. of Plankton Research 24(12), pp. 1265–1276, 2002. Has many images of the earliest development stages of krill.

- ^ Brinton, E.; Ohman, M. D.; Townsend, A. W.; Knight, M. D.; Bridgeman, A. L.: = 4-10039-22-1633327-0 Euphausiids of the World Ocean, World Biodiversity Database CD-ROM Series; Springer Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-540-14673-3.

- ^ Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.: Euphausiids; accessed 16 June 2005.

- ^ Buchholz, F.: = w7capjjptvm7ebtx Experiments on the physiology of Southern and Northern krill, Euphausia superba and Meganyctiphanes norvegica, with emphasis on moult and growth — a review, Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology 36(4), pp. 229–247, 2003.

- ^ Hyoung-Chul Shin; Nicol, S.: Using the relationship between eye diameter and body length to detect the effects of long-term starvation on Antarctic krill Euphausia superba. Mar Ecol Progress Series (MEPS) 239:157–167; 2002.

- ^ Marinovic, B.; Mangel, M.: Krill can shrink as an ecological adaptation to temporarily unfavourable environments, Ecology Letters 2, pp. 338–343; Blackwell Science, 1999.

- ^ CCAMLR: Harvested species: Krill (Eupausia superba). Accessed June 20 2005.

- ^ a b Nicol, S.; Foster, J.: = ok Recent trends in the fishery for Antarctic krill, Aquat. Living Resour. 16, pp. 42–45; 2003.

- ^ Haberman, K: Answers to miscellaneous questions about krill, February 26 1997. Accessed September 6 2007.

Further reading

- Boden, Brian P.; Johnson, Martin W.; Brinton, Edward: Euphausiacea (Crustacea) of the North Pacific. Bulletin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Volume 6 Number 8, 1955.

- Brinton, Edward: The distribution of Pacific euphausiids. Bulletin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Volume 8, no. 2, pages 51–269. 1962.

- Brinton, Edward: Euphausiids of Southeast Asian waters. Naga Report volume 4, part 5. La Jolla: University of California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 1975.

- Conway, D. V. P.; White, R. G.; Hugues-Dit-Ciles, J.; Galienne, C. P.; Robins, D. B.: Guide to the coastal and surface zooplankton of the South-Western Indian Ocean, Order Euphausiacea, Occasional Publication of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom No. 15, Plymouth, UK, 2003.

- Everson, I. (ed.): Krill: biology, ecology and fisheries. Oxford, Blackwell Science; 2000. ISBN 0-632-05565-0.

- Mauchline, J.: Euphausiacea: Adults, Conseil International pour l'Exploration de la Mer, 1971. Identification sheets for adult krill with many line drawings. PDF file, 2 Mb.

- Mauchline, J.: Euphausiacea: Larvae, Conseil International pour l'Exploration de la Mer, 1971. Identification sheets for larval stages of krill with many line drawings. PDF file, 3 Mb.

- Tett, P.: The biology of Euphausiids, lecture notes from a 2003 course in Marine Biology from Napier University. Last accessed July 18 2005.

- Tett, P.: Bioluminescence, lecture notes from the 1999/2000 edition of that same course. Last accessed July 18 2005.