Christian humanism: Difference between revisions

→Literary criticism: Replaced a few incendiary terms |

Added section on "current use" |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Christian views became present in all aspects of society. There was a stressed importance that one must serve God and others. Furthermore, there was a view of human nature that was both hopeful and Christian. All offices, civil, and academic works had religious elements. For example, during the Middle Ages, guilds or livery companies resembled modern-day trade unions. In addition, religion influenced medicine with the Good Samaritan of the Gospels and St. Luke. The idea of free people under God came from this time and spread from the West to other areas of the world. |

Christian views became present in all aspects of society. There was a stressed importance that one must serve God and others. Furthermore, there was a view of human nature that was both hopeful and Christian. All offices, civil, and academic works had religious elements. For example, during the Middle Ages, guilds or livery companies resembled modern-day trade unions. In addition, religion influenced medicine with the Good Samaritan of the Gospels and St. Luke. The idea of free people under God came from this time and spread from the West to other areas of the world. |

||

==Current Use== |

|||

Since the most common definition of "Christian," according to the world's largest Christian organizations<ref>See, for example, {{cite book|title=Catechism of the Catholic Church|publisher=Doubleday|year=1994|location=New York|pages=58-60|isbn=0-385-47967-0}} and {{cite web|url=http://www.worldevangelicals.org/aboutwea/statementoffaith.htm|title=Statement of Faith|accessdate=2009-03-12|publisher=World Evangelical Alliance|date=2001-06-27}}</ref>, is mutually exclusive of the most common definitions of "humanism" (offered by the world's largest humanist organizations<ref>See, for example, {{cite web|url=http://www.iheu.org/minimumstatement|title=IHEU Minimum Statement on Humanism|accessdate=2009-03-12|publisher=International Humanist and Ethical Union|date=2008-06-11}} and {{cite web|url=http://www.americanhumanist.org/humanism/|title=Humanism|accessdate=2009-03-12|publisher=American Humanist Association}}</ref>), Christian humanism must necessarily downplay either the most commonly-accepted Christian aspects or the most commonly-accepted humanist aspects. As there are no notable organizations of Christian humanists, claimants of the title are not easily generalized: prominent web pages include both [http://christianhumanist.net/ The Christian Humanist: Religion, Politics, and Ethics for the 21st Century], which claims that it is possible to be a Christian without a belief in God, and [http://www.firstthings.com/article.php3?id_article=3867 Teaching Christian Humanism], which ignores the current use of the term "humanism" in favor of [[humanities]] studies. The term is also used sometimes to indicate [[Renaissance humanism|Renaissance humanists]] that supported the Catholic church<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.christianchronicler.com/history1/christian_humanism.html|last=Hines|first=Michael|authorlink=http://www.christianchronicler.com/michael.html|title=Christian Humanism|work=Church History For the Masses|accessdate=2009-03-12}}</ref>, such as [[Johann Reuchlin]], [[John Colet]], and [[Desiderius Erasmus]], as opposed to those known primarily for their pagan or political contributions to Renaissance philosophy, like [[Giordano Bruno]] or [[Francis Bacon]]. |

|||

== Selected Humanist Teachings of Jesus == |

== Selected Humanist Teachings of Jesus == |

||

Revision as of 01:15, 13 March 2009

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

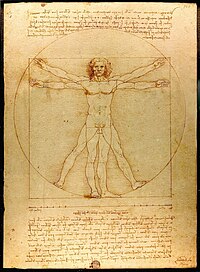

Christian Humanism is the belief that human freedom and individualism are intrinsic (natural) parts of, or are at least compatible with, Christian doctrine and practice. It is a philosophical union of Christian and humanist principles.[1]

Origins

Christian humanism may have begun as early as the 2nd century, with the writings of Justin Martyr. While far from radical, Justin suggested a value in the achievements of Classical culture in his Apology[2] Influential letters by Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa confirmed the commitment to using pre-Christian knowledge, particularly as it touched the material world and not metaphysical beliefs. Already the formal aspects of Greek philosophy, namely syllogistic reasoning, arose in both the Byzantine Empire and Western European circles in the eleventh century to inform the process of theology. However, the Byzantine hierarchy during the reign of Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118) convicted several thinkers of applying "human" logic to "divine" matters. Peter Abelard's work encountered similar ecclesiastical resistance in the West in the same period. Petrarch (1304-1374) is also considered a father of humanism. The traditional teaching that humans are made in the image of God, or in Latin the Imago Dei, also supports individual worth and personal dignity.

Background

Humanists were involved with studia humanitatis and placed great importance on studying ancient languages, namely Greek and Latin, eloquence, classical authors, and rhetoric. All were important for educational curriculum. Christian humanists also cared about scriptural and patristic writings, Hebrew, Church reform, clerical education, and preaching.

In the Renaissance

Christian humanism saw an explosion in the Renaissance, emanating from an increased faith in the capabilities of Man, married with a still-firm devotion to Christianity. Mere Humanism might value earthly existence as something worthy in itself, whereas Christian humanism would value such existence, so long as it were combined with the Christian faith. One of the first texts regarding Christian humanism was Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's Oration on the Dignity of Man, in which he stressed that Men had the free will to travel up and down a moral scale, with God and angels being at the top, and Satan being at the bottom. The country of Pico's nativity, Italy, leaned heavily toward Civic humanism, while the firmer Christian principles took effect in places other than Italy, during what is now called the Northern Renaissance. Italian universities and academia stressed Classical mythology and writings as a source of knowledge, whereas universities in the Holy Roman Empire and France based their teachings on the Church Fathers.

Sparks of Christian Humanism

After the fall of the Roman Empire and the civilization of barbarians, there were thoughts of a more Christianized humanity for society. Western Christian clerics controlled education, since only the monasteries remained as seats of learning. Charlemagne requested for scholars to set up places of learning that would become universities in the twelfth century. Eastern Christians meanwhile continued the late Antique practice of studying in the homes of secular masters, studying the same curriculum of "classical" Greek authors as their predecessors in the Roman period: Homer's Iliad, Plato's dialogues, Aristotle's Categories, Demosthenes' speeches, Galen, Dioscurides, Strabo and others. Christian education in the East largely was relegated to learning to read the Bible at the knees of one's parents and the rudiments of grammar in the letters of Basil or the homilies of Gregory Nazianzus. Western universities including Padua and Bologna, Paris and Oxford resulted from the so-called Gregorian Reform, which encouraged a new kind of cleric clustered around cathedrals, the secular canon. The cathedral schools meant to train clerics for the growing clerical bureaucracy soon served as training grounds for talented young men to train in medicine, law, and the liberal arts of the quadrivium and trivium, in addition to Christian theology. Classical Latin texts and translations of Greek texts served as the basis of non-theological education. A primitive humanism actually started when the papacy began protecting the Northern Cluniacs and Cistercians and the Church formed a unifying bond. Monks and friars went on crusades and St. Bernard counseled kings. Priests were frequently Lord Chancellors in England and in France. Christian views became present in all aspects of society. There was a stressed importance that one must serve God and others. Furthermore, there was a view of human nature that was both hopeful and Christian. All offices, civil, and academic works had religious elements. For example, during the Middle Ages, guilds or livery companies resembled modern-day trade unions. In addition, religion influenced medicine with the Good Samaritan of the Gospels and St. Luke. The idea of free people under God came from this time and spread from the West to other areas of the world.

Current Use

Since the most common definition of "Christian," according to the world's largest Christian organizations[3], is mutually exclusive of the most common definitions of "humanism" (offered by the world's largest humanist organizations[4]), Christian humanism must necessarily downplay either the most commonly-accepted Christian aspects or the most commonly-accepted humanist aspects. As there are no notable organizations of Christian humanists, claimants of the title are not easily generalized: prominent web pages include both The Christian Humanist: Religion, Politics, and Ethics for the 21st Century, which claims that it is possible to be a Christian without a belief in God, and Teaching Christian Humanism, which ignores the current use of the term "humanism" in favor of humanities studies. The term is also used sometimes to indicate Renaissance humanists that supported the Catholic church[5], such as Johann Reuchlin, John Colet, and Desiderius Erasmus, as opposed to those known primarily for their pagan or political contributions to Renaissance philosophy, like Giordano Bruno or Francis Bacon.

Selected Humanist Teachings of Jesus

The Second Great Commandment

"Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself" -- Matthew 22:39, Mark 12:31, Luke 10:27 (also Leviticus 19:18)

“Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the Kingdom prepared for you from the creation of the world. For I was hungry, and you fed me. I was thirsty, and you gave me a drink. I was a stranger, and you invited me into your home. I was naked, and you gave me clothing. I was sick, and you cared for me. I was in prison, and you visited me.’

“Then these righteous ones will reply, ‘Lord, when did we ever see you hungry and feed you? Or thirsty and give you something to drink? Or a stranger and show you hospitality? Or naked and give you clothing? When did we ever see you sick or in prison and visit you?’

“And the King will say, ‘I tell you the truth, when you did it to one of the least of these my brothers and sisters, you were doing it to me!’ -- Matthew 25:34-40

Literary criticism

Christian humanism finally blossomed out of the Renaissance and was brought by devoted Christians to the study of the philological sources of the Greek New Testament and Hebrew Bible. The confluence of moveable type, new inks and widespread paper-making put potentially the whole of human knowledge at the hands of the scholarly community in a new way, beginning with the publication of critical editions of the Bible and Church Fathers and later encompassing other disciplines. This project was undertaken at the time of the Reformation in the work of Erasmus of Rotterdam (who remained a Catholic), Martin Luther (who was an Augustinian priest and led the Reformation, translating the Scriptures into his native German), and John Calvin (who was a student of law and theology at the Sorbonne where he became acquainted with the Reformation, and began studying Scripture in the original languages, eventually writing a text-based commentary upon the entire Christian Old Testament and New Testament except the Book of Revelation). John Calvin was the most prominent of the many figures associated with Reformed Churches that proliferated in Switzerland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and portions of Germany, Hungary, Lithuania, and Poland. Each of the candidates for ordained ministry in these churches had to study the Christian Old Testament in Hebrew and the New in Greek in order to qualify. This continued the tradition of Christian humanism.

Armed with new technologies, Christians from the time of Justin Martyr onwards continued to the present to engage the historical and cultural bases of Christian belief, leading to a spectrum of philosophical and religious stances on the nature of human knowledge and divine revelation. The Enlightenment of the mid-eighteenth century in Europe brought a separation of religious and secular institutions that exemplified a growing rift between Christianity and humanism. Decreasing dependence of philosophers upon religious fundamentalism have led to experiments in various political and social arrangements of the past few centuries around the world, including Internationalist Communism, National Socialism, Fascism, Anarchism, Theocracy, Caesaropapism and various utopian communities. Christians have participated in all of these movements to varying degrees as individuals and institutionally, as have a variety of Deists and Materialists. The broader tradition extends the zone of usage of the term "Christian humanism" and continues to be used widely to describe the vocations of Christians such as Dorothy Sayers, Charles Williams, G. K. Chesterton, Flannery O'Connor, Henri-Irénée Marrou, Dostoevsky, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

Prominent Christian humanists

- A. J. Cronin

- T. S. Eliot

- Erasmus

- Christopher Fry

- Søren Kierkegaard

- Jacques Maritain

- Thomas Merton

- Thomas More

- John Henry Newman

- Boris Pahor

- Blaise Pascal

- Dorothy L. Sayers

- Jim Wallis

- Karol Wojtyla

- Jordan Tidwell

Notes

- ^ Christian World. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1970, p. 42.

- ^ Christian Humanism

- ^ See, for example, Catechism of the Catholic Church. New York: Doubleday. 1994. pp. 58–60. ISBN 0-385-47967-0. and "Statement of Faith". World Evangelical Alliance. 2001-06-27. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ See, for example, "IHEU Minimum Statement on Humanism". International Humanist and Ethical Union. 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2009-03-12. and "Humanism". American Humanist Association. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ Hines, Michael. "Christian Humanism". Church History For the Masses. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink=

References

- Arnold, Jonathan. “John Colet- Preaching and Reform at St. Paul’s Cathedral, 1505-1519.” Reformation and Renaissance Review: Journal of the Society for Reformation Studies 5, no. 2 (2003): 204-209.

- D’Arcy, Martin C. Humanism and Christianity. New York: The World Publishing Company, 1969

- Lemerle, Paul. Byzantine humanism: the first phase: notes and remarks on education and culture in Byzantium from its origins to the 10th century trans. Helen Lindsay and Ann Moffatt. Canberra, 1986.

See also

External links

- No Christian humanism? Big mistake., Online Catholics, by Peter Fleming. (Accessed 2 August 2006)

- Christian Humanism, a website maintained by John P. Bequette, Ph.D., Historical Theology

- [1], a website maintained by Arthur G. Broadhurst

- [2]